Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

The Blue Blanket

Each week the Centre for Research Collections receives two deliveries of Special Collection items from the library annexe. Usually these items go back to the annexe when the reader is finished with them, but occasionally we choose to keep the item in the main library, especially if its contents are closely related to other items in the collections. This happened recently with a journal requested by Fiona Donaldson who is researching the history of the University of Edinburgh Reid Concerts.

The item is called The Blue Blanket, An Edinburgh Civic Review. Four issues of the journal were published during 1912 and its contents relate to a number of special collection items.

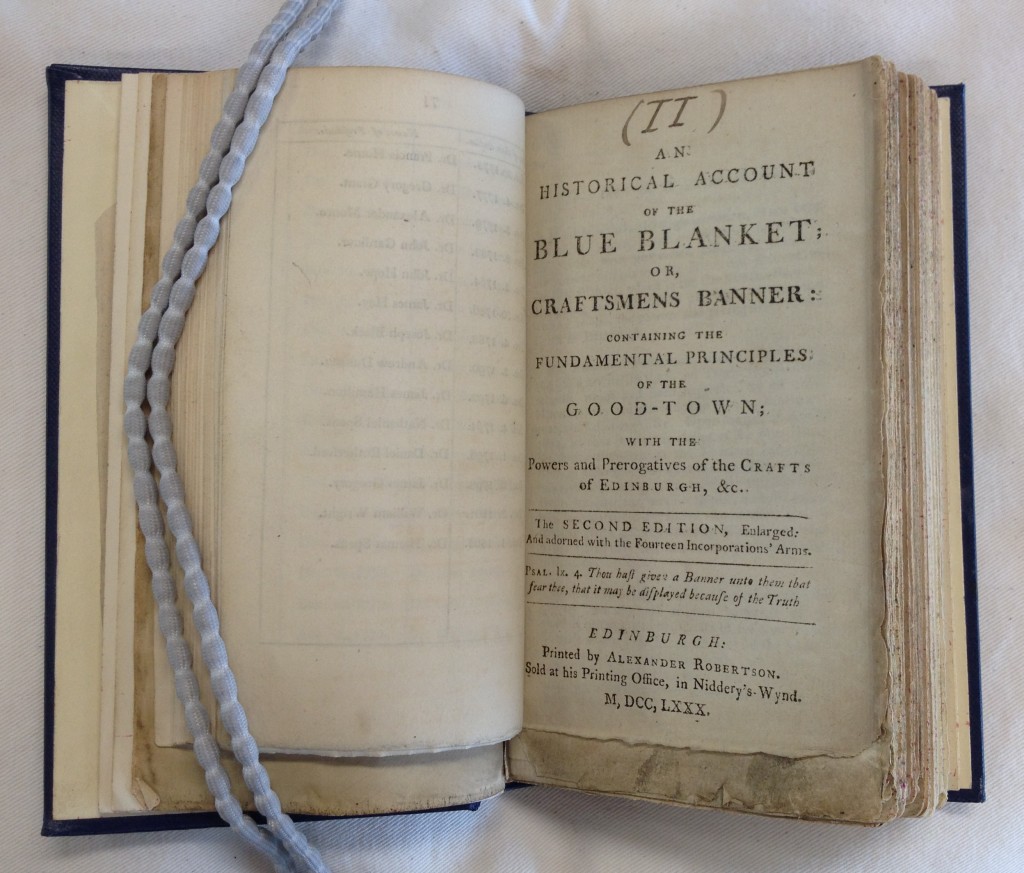

The title of the journal is inspired by banner of Edinburgh Craftsmen. Our rare book collections include a 1780 pamphlet about the Blue Blanket and the craftsmen of Edinburgh:

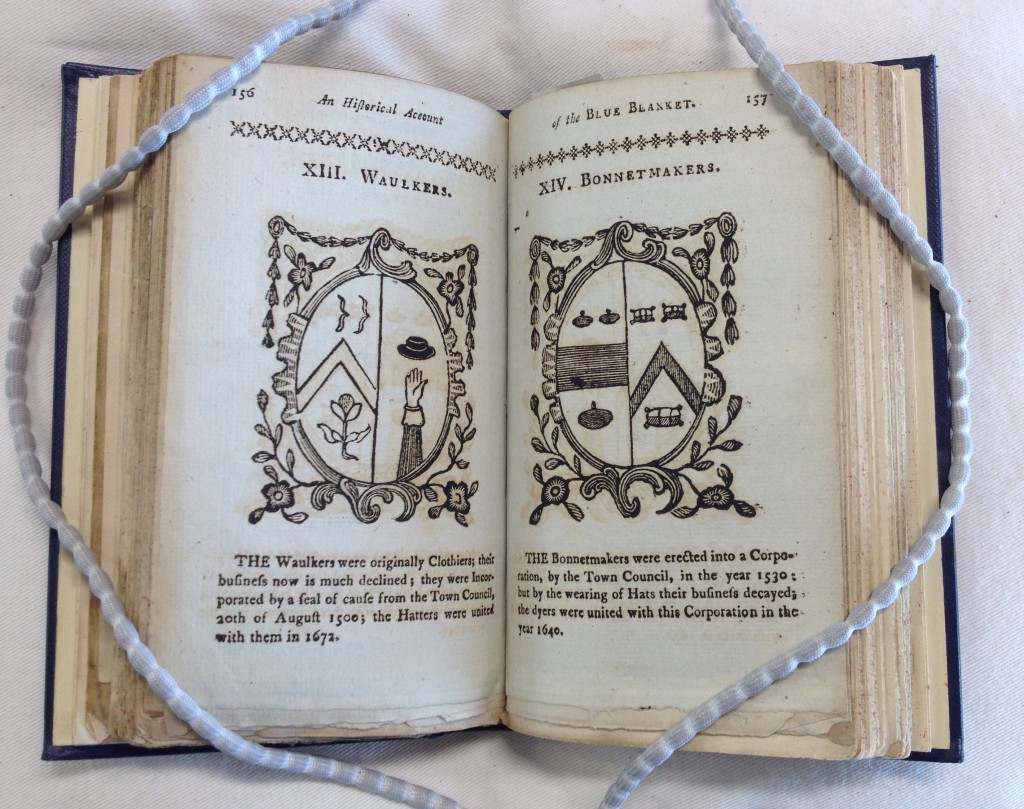

The Historical Account of the Blue Blanket includes illustrations of the emblems of different crafts and guilds, such as the Waulkers and Bonnet Makers:

The journal includes a number of articles by Marjory Kennedy-Fraser (1857-1930), singer, pianist, folk song collector and arranger. The Centre for Research Collections holds her archives, including personal correspondence, manuscripts and musical fragments. Further information can be found on the Archives and Manuscripts Catalogue: http://www.archives.lib.ed.ac.uk/

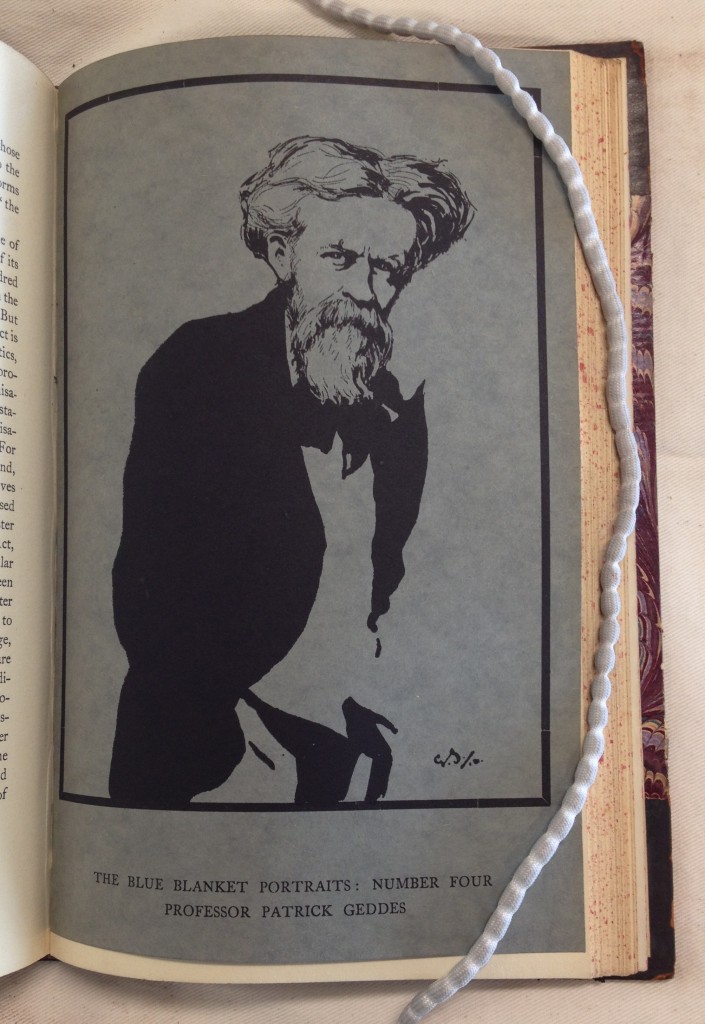

Each issue of The Blue Blanket included a portrait of a notable individual. The portrait for October 1912 was of Professor Patrick Geddes (1854-1932). Geddes was a biologist, sociologist, geographer and town planner. Our collections hold a number of items relating to Geddes, including correspondence to Sir Donald Francis Tovey (1884-1932) and papers relating to the Outlook Tower (some of the photographs from this collection can be seen on the online image collection).

The Blue Blanket can be consulted at the Centre for Research Collections: www.ed.ac.uk/is/crc

Fran Baseby, Service Delivery Curator

My first week as an intern and how it led to the destruction of a city

Jamie started as an intern at the Centre for Research Collections last week, here he tells us about his first few days.

I have just finished my first of eight weeks as a Marketing and Outreach Intern with the CRC, and what a week it has been. After a quick induction the first week has been filled with a mixture of meeting all of the fascinating people working in the department as well as gathering and researching ideas for some of the projects I am going to be working on.

Since I have started, my mind has been blown at least once a day by the interesting things that everyone is working on, and the more this happens the more eager I have been to make my internship successful so we can share some of the stories I have heard with everyone else!

On that subject, here is a little bit more about what I’m doing. As a marketing and outreach intern I’m looking over some of the existing strategies as well as researching, and possibly creating, new ones. Basically I’m looking at ways in which to reach out to more people and let them know about the department and give them a better understanding about what everyone does. I am finding it quite exciting because I get to meet and discuss with everyone all about their roles so I can have a better idea of how to promote everything. By this point you are probably wondering how this led to the destruction of a city.  [Just one of many scenes of devastation included in the photo album of Caen]

[Just one of many scenes of devastation included in the photo album of Caen]

Well, it started with all the news surrounding the D-Day Anniversary, I started asking around to see if anyone had information about a collection relating to this that we could post to our Facebook and Twitter pages. I was directed to a photo album in the collection showing pictures and postcards of the city of Caen in Normandy. The city of Caen was first attacked on D-Day by the allies, but initial assaults were unsuccessful and the battle for Caen ended up waging on for most of June and July. During this battle Caen suffered from heavy bombing and destruction of a lot of its buildings. The photo album I looked through was mostly before and after pictures and it was sad to see many beautiful buildings on postcards and then next to it a photo of the same spot but with nothing more than a pile of rubble. The album had been presented by a Professor John Orr, who was a professor of French here. In the catalogue book there was another entry that was a collection of telegrams and newspaper clippings from John Orr, so I decided look for more information behind the Professor’s link with Caen. Going through this collection I found out that Professor Orr was the Chairman of the Edinburgh-Caen Fellowship, and worked hard on getting the people of Edinburgh to donate food, money and emergency items to Caen following the destruction of their homes.

[Two images showing before and after the assaults]

I could go into a lot more detail on what I found out about the Professor and Caen but I think that I’ve given enough for a taster. If you want to find out more you could pop to the Centre for Research Collections’ Reading Room in the Main Library and take out the album yourself and read all about these important events in our history.

I am sorry to disappoint those of you looking to find out how I caused the destruction of a city! If you haven’t realised, it was about how my internship led on to finding out about Caen. I am a little clumsy but have never done anything like destroying an entire city… yet. I hope you’ve enjoyed my first blog – hopefully they’ll let me do another one…

Thank you for reading, and thank you to DIU for supplying the images.

Jamie

Employ.Ed Hidden Collections Intern – Week 1

The Library Annexe will be joined for the next 8 weeks by Nik Slavov, who is working for the University as part of the Employ.Ed on Campus summer internship programme, in collaboration with the Careers Service. Nik is our Hidden Collections Intern, who is tasked with understanding and prioritising print books stored in the Library Annexe, that are not on the Library’s online catalogue. The eventual goal is to make unique material available for the user community.

Here Nik reflects on his first week at the Library Annexe.

Carl Jones, Library Annexe Supervisor

—

My first week at the Library Annexe now behind me, it would appear it is now time for me to look back and see how that went.

It feels like I haven’t seen anything yet. On the other hand, considering how much I’ve learned about the House of Lords, the native population of Oceania, reclaiming land for ironsand processing, Australasian literature in the 70’s, Antarctica, dairy farming, soil erosion and pollution (it is actually quite scary), New Zealand’s defence program and a number of other topics that I had never thought to occupy my brain with, all of that being just a side effect of organising a few shelves at Annexe 1…

Well, considering all that, I still haven’t even scratched the surface of what’s there. If my math’s any good, I’ve seen less than 0.05 % of what is held in that room only. At this point, Pratchett’s theory of L-space seems very plausible (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L-Space#L-space). The sheer mass of books distorts the space-time continuum, which is why the Library Annexe is way bigger on the inside.

The team is lovely. In all fairness, given the randomness and rareness of my encounters with other human beings within the Annexe, and the alleged hallucinogenic effect of the fungus that develops in old books, I am not entirely certain they actually exist, but in case I didn’t make you guys up – it’s lovely working with you. Or at least, you know, in the same building, or the one next door. Having lunch together. Occasionally. And sometimes overhearing conversations on the radio…

At least it clearly says in the office that this is a Vashta Nerada free workspace, which is a relief. And apparently there have been no Velociraptor-related work accidents in a bit less than a year (is that really good? I should look into that. There ought to be a book with statistics on the topic in the Annexe somewhere. I can’t find one on the catalogue, but I couldn’t find the New Zealand Agriculture and Fisheries Department report from 1968 on the catalogue either, yet I am certain I had it in my hands yesterday.

Unless, you know… fungus.*

Nik Slavov, Hidden Collections intern.

(*For pedantry’s sake, I’d like to point out that there is no active mould in any of the Library Annexe Collections! -ed.)

Search for Vashta Nerada and other resources using Searcher

The Conservation Studio (fungus experts)

Data journals – an open data story

Here at the Data Library we have been thinking about how we can encourage our researchers who deposit their research data in DataShare to also submit these for peer review.

Why? We hope the impact of the research can be enhanced with the recognised added-value of peer review. Regardless whether there is a full-blown article to accompany the data.

We therefore decided recently to provide our depositors with a list of websites or organisations where they could do this.

I pulled a table together, from colleagues’ suggestions, from the PREPARDE project and the latest RDM textbook. And, very much in the Open Data spirit, I then threw the question open on Twitter:

“[..]does anyone have an up-to-date list of journals providin peer review of datasets (without articles), other than PREPARDE? #opendata”

…and published the draft list for others to check or make comments on. This turned out to be a good move. The response from the Research Data Management community on Twitter was very heartening, and colleagues from across the globe provided some excellent enhancements for the list.

That process has given us confidence to remove the word ‘Draft’ from the title – the list, this crowd-sourced resource, will need to be updated from time-to-time, but we are confident that we’ve achieved reasonable coverage of the things we were looking for.

Another result of this search was the realisation that what we had gathered was in fact quite clearly a list of Data Journals. My colleague Robin Rice has now added a definition of that term to the list, and we will be providing all our depositors with a link to it:

https://www.wiki.ed.ac.uk/display/datashare/Sources+of+dataset+peer+review

The Harvard Open Access Initiatives

On Tuesday 10th June we are privileged to have a visit from Stuart Shieber, Faculty Director for the Office of Scholarly Communications, Harvard University. Stuart has kindly agreed to give a seminar looking at the approaches Harvard University have taken to Open Access.

This session is aimed at library & information professionals, research administrators and interested academics and research students. The session will take place in Appleton Tower 2.14 from 10.00am to 11.30am so if you are interested in Open Access and Scholarly Communications, I would encourage you to come along.

Please register for this event at https://www.events.ed.ac.uk/index.cfm?event=book&scheduleID=10504

The Pencil of Nature

Two of my favourite photographs in the Centre for Research Collections come from The University of Edinburghs copy of William Henry Fox Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature“. Shelfmark Df.3.85 .The book also contains an exceptional capital letter T complete with small dragon like creature with a vine like tongue. As can be seen below.

The two images that impress from the book are minimal images that to me feel very modern but have a profound sense of the time they were created through the use of the calotype technique. However i think these images create a wonderful time portal and makes us think of now as well as one hundred and seventy years ago when they were created. I have included whole and detailed views of both of the photographs. Further images from the book can be found here.

Malcolm Brown, Deputy photographer.

Better together or better apart? Some useful resources on the Scottish referendum.

On the 18th September 2014 Scotland will vote yes or no to independence. There are a wealth of online resources available that can help with your research or help to inform your vote on the 18th September and here are just a small number that you may find useful.

Referendum on Independence Key Texts has been put together by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and is intended to be useful to those seeking information on the Referendum on Independence for Scotland, and on the debate around the Referendum. Every effort is made to ensure that both sides of the debate (and neutral commentators) are covered. It is not an exhaustive resource and does not include material from the media e.g. BBC, newspapers, etc., or personal blogs, twitter, etc., however, there are a wide range of resources covered. Read More

Referendum on Independence Key Texts has been put together by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) and is intended to be useful to those seeking information on the Referendum on Independence for Scotland, and on the debate around the Referendum. Every effort is made to ensure that both sides of the debate (and neutral commentators) are covered. It is not an exhaustive resource and does not include material from the media e.g. BBC, newspapers, etc., or personal blogs, twitter, etc., however, there are a wide range of resources covered. Read More

Digital Scholarship Day of Ideas: Data

The theme of this year’s ‘Digital Scholarship Day of Ideas’ (14th May) focused on ‘data’ and what data is for the humanities and social sciences. This post summarises the presentation of Prof Annette Markham, the first speaker of the day. She started her presentation with an illustration of Alice in Wonderland. She then posed the question: What does data mean anyway?

Markham then explained how she had quit her job as a professor in order to enquire into the methods used in different disciplines. Since then, she has thought a lot about method and methodologies, and run many workshops on the theme of ‘data’. In her view, we need to be careful when using the term ‘data’ because although we think we are talking about the same thing we have different understandings of what the term actually means. So, we need to critically interrogate the word and reflect upon the methodologies.

Markham then explained how she had quit her job as a professor in order to enquire into the methods used in different disciplines. Since then, she has thought a lot about method and methodologies, and run many workshops on the theme of ‘data’. In her view, we need to be careful when using the term ‘data’ because although we think we are talking about the same thing we have different understandings of what the term actually means. So, we need to critically interrogate the word and reflect upon the methodologies.

Markham talked about the need to look at ‘methods’ sideways, we need to look at them from above and below. We need to collate as many insights into these methods as possible; we might then understand what ‘data’ means for different disciplines. Sometimes, methods are related to funding, which can be an issue in the current climate, because innovative data collection procedures that might not be suitable for archival aren’t that valuable to funders. The issue is that not all research can be added to digital archives. For an ethnographer, a stain of coffee in a fieldwork notebook has meaning, but this subtle meaning cannot be archived or be meaningful to others unless digitised and clearly documented.

Drawing on Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind (1972), she asked us to think about ‘frames’ and how these draw our attention to what is inside and dismiss what lays outside. If you change the frame with which you look, it changes what you see. She showed and suggested using different frames. For example there are: traditional frames, structures like the sphere, molecular structures. Different structures afford different ways of understanding, and convey themes and ideas that are embedded within them.

To use another example, she used an image of McArthur’s Universal Corrective Map of the World to illustrate how our understanding of our environment changes when information is shown and structured in a different and unexpected way.

- What happens when we change the frame?

- How does the structure shape the information and affect the way we engage with it?

Satellite image of McArthur’s Austral-centric view of the world [Public domain]

1. How do we frame culture and experiences in the 21st Century? How has our concept of society changed since the internet?

Continuing the discussion on frames, she spoke about how the internet has brought on a significant frame shift. This new frame has influenced the way we interact with media and data. To illustrate this, she showed work by Sparacino, Pentland, Davenport, Hlavac and Obelnicki, who in the project the ‘City of News’ (Sparacino, 1997) addressed this frame shift caused by the internet. The MIT project (1996) presented a 3D information browsing system, where buildings were the information spaces where information would be stored and retrieved. Through this example, Markham emphasized how our interaction with information and the methods we use for looking at social culture are changing, and so are the visual-technical frames we use to enquire into the world.

2. How do we frame objects and processes of enquiry?

She argued that this framing of objects and processes hasn’t changed enough. If we were to draw a picture or map of what research is and how the data in any research project is structured, we would end up with a multi-dimensional mass of connected blobs and lines instead of with a neatly composed bi-dimensional picture frame (research looks more like a molecular structure than like a rectangular frame). However, we still associate qualitative research with traditional ethnographic methods and we see quite linear and “neat and tidy” methods as legitimate. There is a need to look at new methods of collecting and analysing research ‘data’ if we are to enquire into socio-cultural changes.

3. How do we frame what counts as proper legitimate enquiry?

In order to change the frame, we have to involve the research community. The frame shift can happen, even if slowly, when established research methods are reinvented. Markham used 1960s feminist scholars as an example, for they approached their research using a frame that was previously inconceivable. This new methodological approach was based on situated knowledge production and embodied understanding, which challenged the way in which scientific research methods had been operating (more on the subject, (Haraway 1988). But in the last decade at least we are seeing an upsurge of to scientific research methods – evidence based, problem solving approaches – dominating the funding and media understanding of research.

So, what is DATA?

‘Data’ is often an easy term to toss around, as it stands for unspecified stuff. Ultimately, ‘data’ is “a lot of highly specific but unspecified stuff”, that we use to make sense of the world around us, a phenomenon. The term ‘data’ is a arguably quite a powerfully rhetorical word in humanities and social sciences, in that it shapes what we see and what we think.

The term data comes from the Latin verb dare, to give. In light of this, ‘data’ is something that is already given in the argument – pre-analytical and pre-semantics. Facts and arguments might have theoretical underpinnings, but data is devoid of any theoretical value. Data is everywhere. Markham referring to Daniel Rosenberg‘s paper ‘Data before the fact’, pointed out that facts can be proved wrong, and then they are no longer a facts, but data is always data even when proven wrong. In the 80s, she was trained not to use the term ‘data,’ they said:

“we do not use it, we collect material, artifacts, notes, information…”

Data is conceived as something that is discrete, identifiable, disconnected. The issue, she said was that ‘data’ poorly represents a conversation (gesture and embodiment), the emergence of meaning from non verbal information, because when we extract things from their context and then use them as a stand-alone ‘data’, we loose a wealth of information.

Markham then showed two ads (Samsung Galaxy SII and Global Pulse) to illustrate her concerns about life becoming data-fied. She referenced Kate Crawford’s perspective on “big data fundamentalism”, because not all human experiences can be reduced to big data, to digital signals, to data points. We have to trouble the idea of thinking about “humans (and their data) as data”. We don’t understand data as it is happening, and “data has never been raw”. Data is always filtered, transformed. We need to use our strong and robust methods of enquery, and that these do not necessarily focus on data as the centre stage, it may be about understanding the phenomenon of what we have made,this thing called data. We have to remember that that’s possible.

Data functions very powerfully as a term, and from a methodological perspective it creates a very particular frame. It warrants careful consideration, especially in an era where the predominant framework is telling us that data is really the important part of research.

References

- Image of Alice in Wanderland after original illustration by Danny Pig (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- Sparacino, Flavia, A. Pentland, G. Davenport, M. Hlavac and M. Obelnicki (1997). ‘City of News’ in Proceedings of Ars Electronica Festival, Linz, Austria, 8-13 Sep.

- Bateson, Gregory (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind: collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution, and epistemology. Aylesbury: Intertext.

- Frame by Hubert Robert [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Sphere by anonymous (CC 1.0) [Public Domain]

- Image of 3D structure (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Map by Poulpy, from work by jimht[at]shaw[dot]ca, modified by Rodrigocd, from Image Earthmap1000x500compac.jpg, [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Rosenberg, Daniel (2013). ‘Data before the fact’ in Lisa Gitelman (ed.) “Raw data” is an oxymoron. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, pp. 15–40.

More about

- Dr Annette Markham

- Digital Scholarship Day of Ideas: Data (videos of the presentations)

Rocio von Jungenfeld

Data Library Assistant

Whale hunting: New documentary for broadcast on BBC Four

The story of Britain’s whale hunters is to be broadcast across the UK in a new 2-part documentary on BBC Four on Monday 9 June and Monday 16 June. The documentary has been produced by ‘KEO films’, and in the second episode some material from the Salvesen Archive will appear. The collection had been given to us on permanent loan in 1969, and with subsequent additions, and was finally gifted by Christian Salvesen Investments Limited in 2012.

Recently a ‘Keo films’ researcher spent some days looking at material from the Salvesen archive before travelling to South Georgia in the South Atlantic to visit the remains of the Salvesen whaling operation there.

In addition to the broadcast in June, the documentary entitled ‘Britain’s Whale hunters: The Untold Story’ will again be transmitted on BBC Two, in Scotland only, later in the year, no date confirmed.

The Salvesen story itself had been an interesting one. In the early decades of the 20th century, the shipping firm Salvesen of Leith, Scotland, led the whaling industry at a time when food oils and other products from the Antarctic were considered an endless resource. Indeed, whaling dominated the Salvesen business. In later years – the 1960s and 1970s – the firm had diversified into the tanker fleet business, shipping steel and coke to Norway for the Norwegian shipbuilding and steel industries, factory fishing trawlers, and then to shore-based cold storage, canning, property development and also to house-building. Then, in October 2007, the French based transport and logistics provider Norbert Dentressangle announced that it had reached an agreement to acquire Christian Salvesen.

The images shown here are also from the Salvesen Archive and show the Company vessels ‘Coronda’ and ‘New Sevilla’ at Leith Harbour in South Georgia, and crew on board a prospecting cruise to South Georgia and Antarctica in 1913-1914.

Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts

Science: Media Friendly?

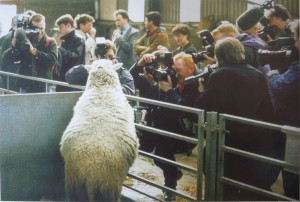

Nowadays we are more than accustomed to scientists appearing on television and radio to talk about their research or engage in debates about the social, political and ethical implications of science. The archives of the Roslin Institute and the personal papers of Ian Wilmut testify to the increasingly public-facing role of scientists, which a glance at the file upon file of press enquiries about Dolly the sheep reveals. In the book The Second Creation, Ian Wilmut states that ‘nothing could have prepared us for the (literally) thousands of telephone calls, the scores of interviews, the offers of tours and contracts and in some cases the opprobrium’ which would follow the announcement of Dolly’s birth. The relationship between science and the media can be a prickly one – Dolly’s birth led to hysterical press reactions about potential human cloning – but it also allows for open public debate about the wider implications of scientific research which can affect us all.

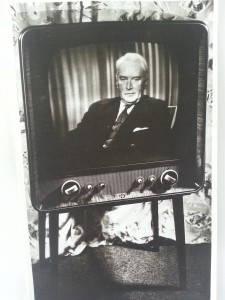

Historically, we can trace the continuing increase in scientists’ public presence in tandem with the growth of the media industry throughout the twentieth century. The personal papers of Alan Greenwood and C.H. Waddington reveal that they actively utilised television and radio as forums for their work.

One of the earliest examples in the archives dates from 1936. Australian poultry geneticist Alan Greenwood‘s papers refer to two BBC radio broadcasts given by him titled ‘Junior Geography: the Empire Overseas’. There is also a copy of Greenwood’s script about the Australian outback for the Scottish Sub-Council for School Broadcasting, which begins ‘Good Afternoon, Boys and Girls – To-day we are going to make an excursion into the Australian Bush…’

C.H. Waddington supplemented his professional duties as lecturer, researcher, writer and director of the Institute of Animal Genetics with frequent appearances on television and radio, as his archives reveal. During the 1960s, for example, he participated in BBC broadcasts debating and discussing the existence of God, ‘the appearance of design in evolution’, Lysenkoism, and the social implications of biological research, most notably in the controversial programme ‘Towards Tomorrow: Assault on Life’, broadcast in December 1967. Waddington very much saw the biological sciences as woven closely into the fabric of society, with public debate an important facet of this. Writing to Waddington about his appearance on the BBC series ‘Some Aspects of Modern Biology’ in March 1967, science correspondent and adviser Gerald Leach wrote that ‘you were the only scientist that I’ve seen in this series who had any kind of feeling at all that one might set up social goals and try and work towards them.’

These ‘social goals’ are an important aspect of scientific research. Contentious as the media’s portrayal of science and scientists can often be, it puts a human face to specialist terminology, complex theories and vast data sets. It broadens our awareness of scientific discovery and its potential for the world and, importantly, allows us to respond.

Clare Button

Project Archivist

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....