Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 19, 2025

Win £50 book token!

This summer the Library is launching a new Discovery service which will combine the functionality of the Library Catalogue and Searcher into one single search tool that will help you to easily discover the resources you need for your study and research.

The Library will be using Primo for the new discovery service but “Primo” is just the product name. We would like you to help name the service for our Library. If your suggested name is chosen then you will win £50 worth of book tokens. The competition is open to all staff and students of the University. Entries must be received by 5pm (GMT) on Friday 20th February 2015.

For more information on the competition and how to enter see:

What’s in a name? Help us decide. Read More

Getting to the Heart of the Matter

This blog post starts where I left off last time (with another pun!) and details my efforts on the Thomson-Walker medical print collection thus far, describing the first phase of the project.

After I had spent a few days surveying the boxes of prints I began to get a better idea of how to best approach treating the entire collection and started to investigate various rehousing ideas, as well as experimenting with numerous adhesive removal techniques. The main requirement for the adhesive removal was to be able to lift a range of adhesives, at various stages of degradation on differing primary supports allowing for the safe and quick removal of carrier and adhesive for the majority of the 2500 prints. It was decided quite early on during the survey that a poultice would work best for such a task. A poultice is a swelling agent commonly made with a viscous substance used to slowly and controllably release moisture. This would permit a number of objects to be treated simultaneously and, if the correct poultice method was adopted, to remove an adhesive easily and equally – such a technique would not only be beneficial for the wellbeing of the prints, but would also be time and cost effective.

I began my experimentation with the Albertina poultice, a ready for use amylase poultice that removes un-swellable starch pastes. I was sent a sample kit, which comprised of two interleaving silk tissue papers, an amylase poultice, and a small piece of blotter. I experimented with this system on a variety of prints from the collection, however whilst the poultice worked wonderfully on some adhesives and carriers (presumably starch based) the poultice failed on others. Because of this I believed that despite the Albertina poultice working well on certain adhesives, and with the added benefit of reusability (the Albertina poultice can be stored and reused for at least 12 months) it was not a suitable option considering the varied adhesives present within the collection.

Next, I experimented with high viscosity carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salt poultice strips, a method devised at the Book and Paper Conservation Studio at the University of Dundee. To be efficient and economical the CMC is wrapped in Japanese tissue to create individual poultice strips that are then placed directly onto the carrier of the adhesive and left to take action. I discovered that to easily remove the adhesive and carrier the poultice strip only needed to be in place for about 20 minutes and thereafter the adhesive/carrier could be gently lifted and removed. This particular poultice worked on a variety of tape and adhesives and the reusable strips were easy to handle and manipulate according to shape and size of the adhesive layer. So far the poultice has been successful on a range of tapes and adhesives including starch based adhesives, animal glue, and masking and glassine tape.

And so, there you have it, the Carboxymethyl Cellulose strips created perfect and painless poulticing – a swift operation, if I do say so myself…

Post by Samantha Cawson, Conservation Intern

Trial – ACLS Humanities E-Book package

We have trial access to ACLS Humanities E-Book package until the 5th April.

We have trial access to ACLS Humanities E-Book package until the 5th April.

This electronic resource includes 4,315 full-text, cross-searchable books in the humanities selected by scholars for their continuing importance for research and teaching. Lists of titles can be found online at: http://www.humanitiesebook.org/titlelist.html.

The project includes both in-print and out-of-print books and many prize-winning works. It is a ongoing collaboration of the American Council of Learned Societies, various constituent member learned societies of the ACLS (http://www.humanitiesebook.org/societies.html), and over 100 publishers. 300-500 titles are added every year.

To access HEB, please go to http://www.humanitiesebook.org.

–> Select Browse from top toolbar.

–> Click on any title. This will bring you to a screen with information about the book.

–>To view the full text of a chapter, click on the chapter title in the table of contents. You can select Search from the top toolbar to look for specific titles. To browse through HEB’s special series, select The Collection from the top toolbar and click on the links for series such as the College Art Association Monographs: http://www.humanitiesebook.org/the-collection/series_CAA.html and the Cambridge University Press series: http://www.humanitiesebook.org/the-collection/series_CamUP.html, the Society of Biblical Literature series: http://www.humanitiesebook.org/the-collection/series_SBL.html, and the Records of Civilization series: http://www.humanitiesebook.org/the-collection/series_ROC.html.

HEB Titles Online as of Dec. 2014

To download the spreadsheet, please visit:

http://www.humanitiesebook.org/the-collection/default.html

This spreadsheet, with 4,315 titles in all, represents the total number of books on the HEB site as of Dec. 2014. This list is formatted as a downloadable Excel spreadsheet and includes author, title, publication information, ISBN, LC catalog number, subject area, direct URL, and date live on HEB.

Fields currently covered include Area and Historical Studies in the following: African, American, Asian, Australasian/Oceanian, Byzantine, Canadian, Caribbean, Central European, Comparative/World, Eastern European/Russian, Economic, Environmental, European, Jewish Studies, Latin American, Law, LGBT/Queer Studies, Medicine, Methods/Theory, Middle East, Native Peoples of the Americas, Science/Technology, Women’s Studies. HEB also encompasses the fields of Archaeology, Art and Architectural History, Biblical Studies, Bibliographic Studies, Film and Media Studies, Folklore, Linguistics, Literature, Literary Criticism, Musicology, Performance Studies (theater, music, dance), Philosophy, Political Science, Religion, and Sociology.

Feedback and further info

We are interested to know what you think of this e-book package and platform as your comments influence purchase decisions so please do fill out our feedback form.

A list of all trials currently available to University of Edinburgh staff and students can be found on our trials webpage.

Leading a Digital Curation ‘Lifestyle’: First day reflections on IDCC15

[First published on the DCC Blog, republished here with permission.]

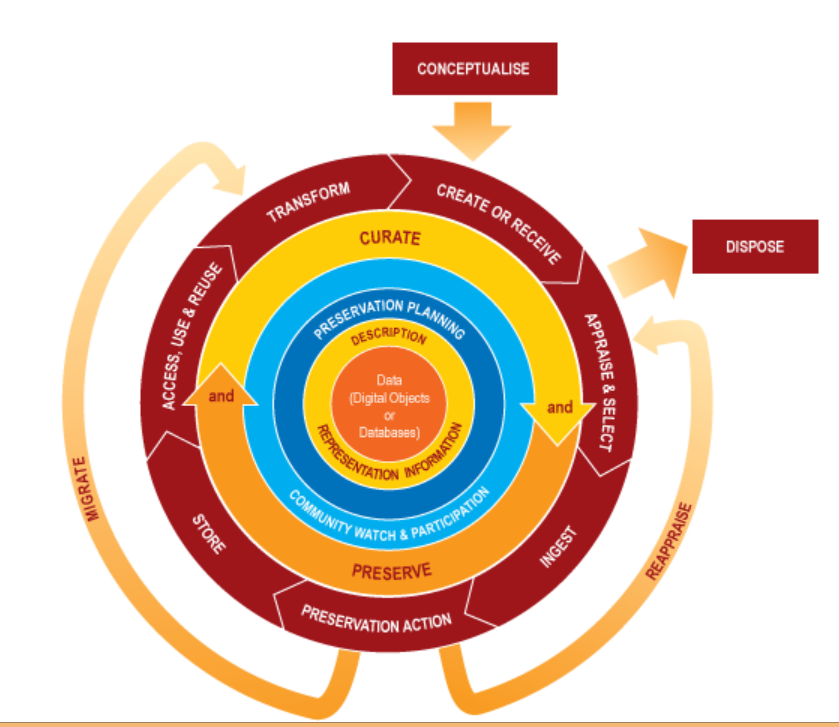

Okay that title is a joke, but an apt one to name a brief reflection of this year’s International Digital Curation Conference in London this week, with the theme of looking ten years back and ten years forward since the UK Digital Curation Centre was founded.

The joke references an alleged written or spoken mistake someone made in referring to the Digital Curation lifecycle model, gleefully repeated on the conference tweetstream (#idcc15). The model itself, as with all great reference works, both builds on prior work and was a product of its time – helping to add to the DCC’s authority within and beyond the UK where people were casting about for common language and understanding in this new terrain of digital preservation, data curation, and – a perplexing combination of terms which perhaps still hasn’t quite taken off, ‘digital curation’ (at least not to the same extent as ‘research data management’). I still have my mouse-mat of the model and live with regrets it was never made into a frisbee.

They say about Woodstock that ‘if you remember it you weren’t really there’, so I don’t feel too bad that it took Tony Hey’s coherent opening plenary talk to remind me of where we started way back in 2004 when a small band under the directorship of Peter Burnhill (services) and Peter Buneman (research) set up the DCC with generous funding from Jisc and EPSRC. Former director Chris Rusbridge likes to talk about ‘standing on the shoulders of giants’ when describing long-term preservation, and Tony reminded us of the important, immediate predecessors of the UK e-Science Programme and the ground-breaking government investment in the Australian National Data Service (ANDS) that was already changing a lot of people’s lifestyles, behaviours and outlooks.

Traditionally the conference has a unique format that focuses on invited panels and talks on the first day, with peer-reviewed research and practice papers on the second, interspersed with demos and posters of cutting edge projects, followed by workshops in the same week. So whilst I always welcome the erudite words of the first day’s contributors, at times there can be a sense of, ‘Wait – haven’t things moved on from there already?’ So it was with the protracted focus on academic libraries and the rallying cries of the need for them to rise to the ‘new’ challenges during the first panel session chaired by Edinburgh’s Geoffrey Boulton, focused ostensibly on international comparisons. Librarians – making up only part of the diverse audience – were asking each other during the break and on twitter, isn’t that exactly what they have been doing in recent years, since for example, the NSF requirements in the States and the RCUK and especially EPSRC rules in the UK, for data management planning and data sharing? Certainly the education and skills of data curators as taught in iSchools (formerly Library Schools) has been a mainstay of IDCC topics in recent years, this one being no exception.

But has anything really changed significantly, either in libraries or more importantly across academia since digital curation entered the namespace a decade ago? This was the focus of a panel led by the proudly impatient Carly Strasser, who has no time for ‘slow’ culture change, and provocatively assumes ‘we’ must be doing something wrong. She may be right, but the panel was divided. Tim DiLauro observed that some disciplines are going fast and some are going slow – depending on whether technology is helping them get the business of research done. And even within disciplines there are vast differences –-perhaps proving the adage that ‘the future is here, it’s just not distributed yet’.

Geoffrey Bilder spoke of tipping points by looking at how recently DOIs (Digital Object Identifiers, used in journal publishing) meant nothing to researchers and how they have since caught on like wildfire. He also pointed blame at the funding system which focuses on short-term projects and forces researchers to disguise their research bids as infrastructure bids – something they rightly don’t care that much about in itself. My own view is that we’re lacking a killer app, probably because it’s not easy to make sustainable and robust digital curation activity affordable and time-rewarding, never mind profitable. (Tim almost said this with his comparison of smartphone adoption). Only time will tell if one of the conference sponsors proves me wrong with its preservation product for institutions, Rosetta.

It took long-time friend of the DCC Clifford Lynch to remind us in the closing summary (day 1) of exactly where it was we wanted to get to, a world of useful, accessible and reproducible research that is efficiently solving humanity’s problems (not his words). Echoing Carly’s question, he admitted bafflement that big changes in scholarly communication always seem to be another five years away, deducing that perhaps the changes won’t be coming from the publishers after all. As ever, he shone a light on sticking points, such as the orthogonal push for human subject data protection, calling for ‘nuanced conversations at scale’ to resolve issues of data availability and access to such datasets.

Perhaps the UK and Scotland in particular are ahead in driving such conversations forward; researchers at the University of Edinburgh co-authored a report two years ago for the government on “Public Acceptability of Data Sharing Between the Public, Private and Third Sectors for Research Purposes,” as a pre-cursor to innovations in providing researchers with secure access to individual National Health Service records linked to other forms of administrative data when informed consent is not possible to achieve.

Given the weight of this societal and moral barrier to data sharing, and the spread of topics over the last 10 years of conferences, I quite agree with Laurence Horton, one of the panelists, who said that the DCC should give a particular focus to the Social Sciences at next year’s conference.

Robin Rice

Data Librarian (and former Project Coordinator, DCC)

University of Edinburgh

Trial – Film Industry Data

We have trial access to Film Industry Data from Academic Rights Press until the 9th March.

We have trial access to Film Industry Data from Academic Rights Press until the 9th March.

Film Industry Data enables the gathering of information about film trends and research into the impact of film across countries and cultures. Films tell us about global culture, politics and society. Now you can get the facts behind the film industry with the exclusive Nielsen backed Film Industry Data collection. This database synthesises movie industry data to help you make new connections, gain valuable insights and tell new stories

Feedback and further info

We are interested to know what you think of this database as your comments influence purchase decisions so please do fill out our feedback form.

A list of all trials currently available to University of Edinburgh staff and students can be found on our trials webpage.

Managing data: photographs in research

In collaboration with Scholarly Communications, the Data Library participated in the workshop “Data: photographs in research” as part of a series of workshops organised by Dr Tom Allbeson and Dr Ella Chmielewska for the pilot project “Fostering Photographic Research at CHSS” supported by the College of Humanities and Social Science (CHSS) Challenge Investment Fund.

In our research support roles, Theo Andrew and I addressed issues associated with finding and using photographs from repositories, archives and collections, and the challenges of re-using photographs in research publications. Workshop attendants came from a wide range of disciplines, and were at different stages in their research careers.

First, I gave a brief intro on terminology and research data basics, and navigated through media platforms and digital repositories like Jisc Media Hub, VADS, Wellcome Trust, Europeana, Live Art Archive, Flickr Commons, Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog (Muybridge http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3a45870) – links below.

Then, Theo presented key concepts of copyright and licensing, which opened up an extensive discussion on what things researchers have to consider when re-using photographs and what institutional support researchers expect to have. Some workshop attendees shared their experience of reusing photographs from collections and archives, and discussed the challenges they face with online publications.

The last presentation tackling the basics of managing photographic research data was not delivered due to time constraints. The presentation was for researchers who produce photographic materials, however, advice on best RDM practice is relevant to any researcher independently of whether they are producing primary data or reusing secondary data. There may be another opportunity to present the remaining slides to CHSS researchers at a future workshop.

ONLINE RESOURCES

- Jisc Media Hub http://jiscmediahub.ac.uk/

- Visual Arts Data Service (VADS) http://www.vads.ac.uk/

- Wellcome Trust Image Collection http://wellcomeimages.org/

- British Library Catalogue of Photographs http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/photographs/

- Europeana http://europeana.eu/

- UK Data Service discover http://discover.ukdataservice.ac.uk/

- Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog http://www.loc.gov/pictures/

- Live Art Archive http://www.bris.ac.uk/theatrecollection/liveart/liveart_archivesmain.html

- Flickr Commons Project https://www.flickr.com/commons

LICENSING

- Intellectual Property Office (IPO) https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/305165/c-notice-201401.pdf

- Bern Convention http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/index.html

- WIPO Copyright Treaty http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=295166

- Copyright lengths: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries%27_copyright_lengths

- Creative Commons License http://creativecommons.org/

- Flickr (CC or Copyright)https://www.flickr.com/explore

- Wikimedia (CC) http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Photographs

- Wikimedia Licensing guide http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Licensing

Cite Them Right – downtime

Cite Them Right will be unavailable between 08:00am and 10:00am on Thursday 12th February. This is due to essential maintenance.

Cite Them Right will be unavailable between 08:00am and 10:00am on Thursday 12th February. This is due to essential maintenance.

Recent acquisition – Sketch-books of Scottish architect Charles Lovett Gill (1880-1960)

Recently, a group of 13 sketch-books by the Scottish architect Charles Lovett Gill were acquired by the Centre for Research Collections (Special Collections) for Edinburgh University Library. Gill was notable for his long-term architectural partnership with Professor Sir Albert Edward Richardson (1880-1964).

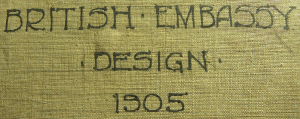

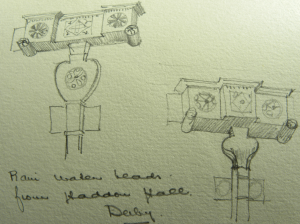

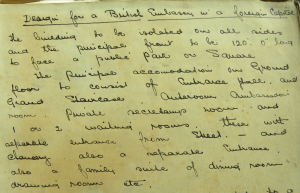

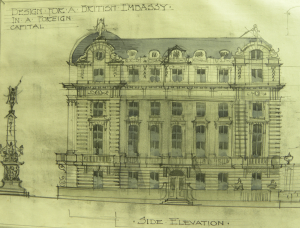

Notes about the ambition for the sketch-book ‘British Embassy design 1905’, by Charles Lovett Gill. Coll-1603.

Gill was born in 1880. He trained as an architect with E. G. Warren of Exeter, and he studied at the Royal Academy Schools. In 1904 he was the Ashpitel Prizeman (an annual architectural award in the name of Arthur Ashpitel) of the Royal Institute of British architects (RIBA), and he became an Associate of RIBA in 1905, and a Fellow in 1915 in recognition for his contribution to architecture in England.

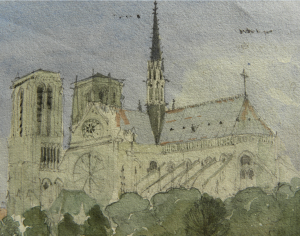

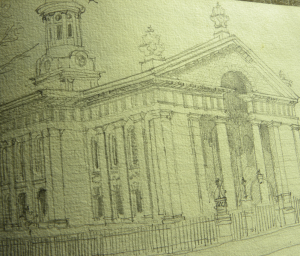

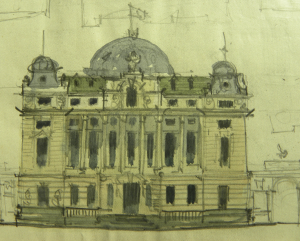

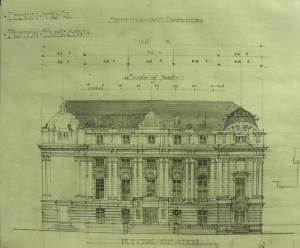

One of the edifices in the sketch-book ‘British Embassy Design 1905’ by Charles Lovett Gill. Coll-1603.

Gill started a practice in London in 1908 and did much work in central London. With Professor Sir Albert Richardson he was joint architect for the Duchy of Cornwall estate in Devon. The Richardson & Gill architectural partnership was eventually dissolved in 1939.

One of the edifices in the sketch-book ‘British Embassy Design 1905’ by Charles Lovett Gill. Coll-1603.

Gill presented a design in the competition for the rebuilding of the Regent Street Quadrant in London, and he was responsible for the facade of the then Regent Street Polytechnic (now part of University of Westminster). Much of his work was in the City of London where he designed Moorgate Hall, Finsbury Pavement and other buildings in Moorgate and elsewhere. Charles Lovett Gill died on 26 March 1960.

One of the edifices in the sketch-book ‘British Embassy Design 1905’ by Charles Lovett Gill. Coll-1603.

The recently acquired collection of Gill sketch-books contain pencil and watercolour tinted sketches of various places done between 1904 and 1941. One of the sketchbooks bound in linen is titled British Embassy Design 1905 and it may be a project set by his tutors. It contains sketches of a number of buildings in Paris and London with neatly finished elevations of a planned and very large Beaux-Arts edifice – a British Embassy in a foreign capital – that would dominate any chosen site. It was a grand building which, according to Gill’s notes in the sketch-book, was to ‘face a public park or square’.

One of the edifices in the sketch-book ‘British Embassy Design 1905’ by Charles Lovett Gill. Coll-1603.

Other sketch-books contain drawings, sometimes colour tinted, of buildings and architectural features in Paris, London and in other parts of Britain.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

Tackling a Library time capsule : The Longforgan Free Church Ministers Library

Regular visitors to New College Library have probably walked past the Longforgan Free Church Ministers Library many times. It sits in custom made glazed bookcases, which are sited on the landing of the entrance to the Library Hall and in the David Welsh Reading Room. The cataloguing of this collection is in progress as part of the Funk Projects, and we’ve recently been pleased to welcome Patrick Murray as our cataloguer, replacing Finlay West who has moved on to new projects.

Regular visitors to New College Library have probably walked past the Longforgan Free Church Ministers Library many times. It sits in custom made glazed bookcases, which are sited on the landing of the entrance to the Library Hall and in the David Welsh Reading Room. The cataloguing of this collection is in progress as part of the Funk Projects, and we’ve recently been pleased to welcome Patrick Murray as our cataloguer, replacing Finlay West who has moved on to new projects.

The Longforgan Library is an attractive part of the New College Library environment, but it’s probably true to say that for many years it has been just that – the books themselves have rarely been consulted. This may have been so from the very beginning – we’ve noticed that books being catalogued recently are in mint condition, some with pages uncut, as though they have never been read. This may fit with the Longforgan Library’s provenance as a gift to the Free Church at Longforgan, Dundee by Mr David Watson, owner of Bullionfield Paperworks at Invergowrie. Part of the Longforgan Library could have begun life as a showpiece collection for David Watson to illustrate his skills in printing and binding to clients.

All this is changing with the benefits of online cataloguing. The Longforgan Library contains many volumes of the Acts of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland from the seventeenth century onwards and the reports of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in the nineteenth century. For the first time these are being requested by readers, with telltale paper slips the evidence that the volumes are in use.

All this is changing with the benefits of online cataloguing. The Longforgan Library contains many volumes of the Acts of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland from the seventeenth century onwards and the reports of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland in the nineteenth century. For the first time these are being requested by readers, with telltale paper slips the evidence that the volumes are in use.

More than that, online cataloguing has revealed the richness of this collection of patristic and theological books, the earliest text printed in 1618. The works of Eusebius of Caesarea and Irenaeus of Lyon sit alongside those of Jean Calvin and John Foxe in a microcosm of New College Library’s historic collections as a whole. And it’s held surprises for us – one of them being that we discovered additional books hidden in concealed compartments in the back of the bookcases.

Castori romanorum cosmographi : tabula quae dicitur Peutingeriana / recognovit Conrad Miller. Ravensburg : Otto Maier, 1888

New College Library LON. 416

This included this fantastic facsimile of the Tabula Peutingeriana or Peutinger’s Tabula. Based on an early fourth or fifth century original, the map covers the area roughly from southeast England to present day Sri Lanka and shows the Roman road network. When we unfolded the map it stretched the length of the office!

The Longforgan Free Church Ministers Library still has treasures to discover. There are cupboards yet to unlock which have books stacked back to back in them, plus there is a further sequence of Longforgan books in a more secure location which includes three early editions of the Babylonian Talmud. Watch this space.

Christine Love-Rodgers – Academic Support Librarian, Divinity

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....