Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 17, 2025

open.ed report

Lorna M. Campbell, a Digital Education Manager with EDINA and the University of Edinburgh, writes about the ideas shared and discussed at the open.ed event this week.

Earlier this week I was invited by Ewan Klein and Melissa Highton to speak at Open.Ed, an event focused on Open Knowledge at the University of Edinburgh. A storify of the event is available here: Open.Ed – Open Knowledge at the University of Edinburgh.

“Open Knowledge encompasses a range of concepts and activities, including open educational resources, open science, open access, open data, open design, open governance and open development.”

– Ewan Klein

Ewan set the benchmark for the day by reminding us that open data is only open by virtue of having an open licence such as CC0, CC BY, CC SA. CC Non Commercial should not be regarded as an open licence as it restricts use. Melissa expanded on this theme, suggesting that there must be an element of rigour around definitions of openness and the use of open licences. There is a reputational risk to the institution if we’re vague about copyright and not clear about what we mean by open. Melissa also reminded us not to forget open education in discussions about open knowledge, open data and open access. Edinburgh has a long tradition of openness, as evidenced by the Edinburgh Settlement, but we need a strong institutional vision for OER, backed up by developments such as the Scottish Open Education Declaration.

I followed Melissa, providing a very brief introduction to Open Scotland and the Scottish Open Education Declaration, before changing tack to talk about open access to cultural heritage data and its value to open education. This isn’t a topic I usually talk about, but with a background in archaeology and an active interest in digital humanities and historical research, it’s an area that’s very close to my heart. As a short case study I used the example of Edinburgh University’s excavations at Loch na Berie broch on the Isle of Lewis, which I worked on in the late 1980s. Although the site has been extensively published, it’s not immediately obvious how to access the excavation archive. I’m sure it’s preserved somewhere, possibly within the university, perhaps at RCAHMS, or maybe at the National Museum of Scotland. Where ever it is, it’s not openly available, which is a shame, because if I was teaching a course on the North Atlantic Iron Age there is some data form the excavation that I might want to share with students. This is no reflection on the directors of the fieldwork project, it’s just one small example of how greater access to cultural heritage data would benefit open education. I also flagged up a rather frightening blog post, Dennis the Paywall Menace Stalks the Archives, by Andrew Prescott which highlights the dangers of what can happen if we do not openly licence archival and cultural heritage data – it becomes locked behind commercial paywalls. However there are some excellent examples of open practice in the cultural heritage sector, such as the National Portrait Gallery’s clearly licensed digital collections and the work of the British Library Labs. However openness comes at a cost and we need to make greater efforts to explore new business and funding models to ensure that our digital cultural heritage is openly available to us all.

Ally Crockford, Wikimedian in Residence at the National Library of Scotland, spoke about the hugely successful Women, Science and Scottish History editathon recently held at the university. However she noted that as members of the university we are in a privileged position in that enables us to use non-open resources (books, journal articles, databases, artefacts) to create open knowledge. Furthermore, with Wikpedia’s push to cite published references, there is a danger of replicating existing knowledge hierarchies. Ally reminded us that as part of the educated elite, we have a responsibility to open our mindsets to all modes of knowledge creation. Publishing in Wikipedia also provides an opportunity to reimagine feedback in teaching and learning. Feedback should be an open participatory process, and what better way for students to learn this than from editing Wikipedia.

Robin Rice, of EDINA & Data Library, asked the question what does Open Access and Open Data sharing look like? Open Access publications are increasingly becoming the norm, but we’re not quite there yet with open data. It’s not clear if researchers will be cited if they make their data openly available and career rewards are uncertain. However there are huge benefits to opening access to data and citizen science initiatives; public engagement, crowd funding, data gathering and cleaning, and informed citizenry. In addition, social media can play an important role in working openly and transparently.

James Bednar, talking about computational neuroscience and the problem of reproducibility, picked up this theme, adding that accountability is a big attraction of open data sharing. James recommended using iPython Notebook for recording and sharing data and computational results and helping to make them reproducible. This promoted Anne-Marie Scott to comment on twitter:

Very cool indeed.

James Stewart spoke about the benefits of crowdsourcing and citizen science. Despite the buzz words, this is not a new idea, there’s a long tradition of citizens engaging in science. Darwin regularly received reports and data from amateur scientists. Maintaining transparency and openness is currently a big problem for science, but openness and citizen science can help to build trust and quality. James also cited Open Street Map as a good example of building community around crowdsourcing data and citizen science. Crowdsourcing initiatives create a deep sense of community – it’s not just about the science, it’s also about engagement.

After coffee (accompanied by Tunnocks caramel wafers – I approve!) We had a series of presentations on the student experience and students engagement with open knowledge.

Paul Johnson and Greg Tyler, from the Web, Graphics and Interaction section of IS, spoke about the necessity of being more open and transparent with institutional data and the importance of providing more open data to encourage students to innovate. Hayden Bell highlighted the importance of having institutional open data directories and urged us to spend less time gathering data and more making something useful from it. Students are the source of authentic experience about being a student – we should use this! Student data hacks are great, but they often have to spend longer getting and parsing the data than doing interesting stuff with it. Steph Hay also spoke about the potential of opening up student data. VLEs inform the student experience; how can we open up this data and engage with students using their own data? Anonymised data from Learn was provided at Smart Data Hack 2015 but students chose not to use it, though it is not clear why. Finally, Hans Christian Gregersen brought the day to a close with a presentation of Book.ed, one of the winning entries of the Smart Data Hack. Book.ed is an app that uses open data to allow students to book rooms and facilities around the university.

What really struck me about Open.Ed was the breadth of vision and the wide range of open knowledge initiatives scattered across the university. The value of events like this is that they help to share this vision with fellow colleagues as that’s when the cross fertilisation of ideas really starts to take place.

This report first appeared on Lorna M. Campbell’s blog, Open World: lornamcampbell.wordpress.com/2015/03/11/open-ed

P.S. another interesting talk came from Bert Remijsen, who spoke of the benefits he has found from publishing his linguistics research data using DataShare, particularly the ability to enable others to hear recordings of the sounds, words and songs described in his research papers, spoken and sung by the native speakers of Shilluk, with whom he works during his field research in South Sudan.

Monsters & Maps Printed under the Watchful Dog

Last week Mercator’s beautiful Atlas sive Cosmographicae found its way into the DIU, only after it arrived did we discover that it was actually his 503rd Birthday, a fact celebrated by google with a Google Doodle http://www.google.com/doodles/gerardus-mercators-503rd-birthday.

American discovery in Special Collections

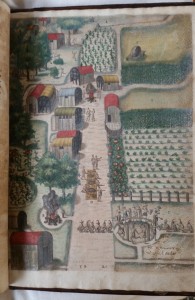

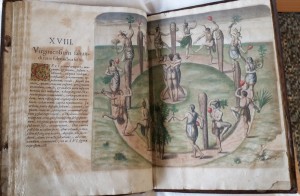

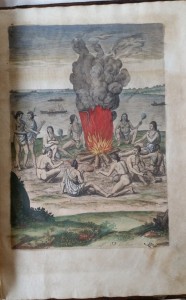

This is the first book to describe and depict native American costume, culture and society for European readers. It was published in 1590 by the enterprising merchant Theodor de Bry, who identified a market for illustrated works on travel and newly discovered lands. He made use of the text written by Thomas Harriot and published in 1588 as A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, and turned it into a Latin edition to reach a wider readership. For this edition de Bry included engraved plates based on the watercolours of English colonist John White, who worked as an artist during the pioneering attempt to settle in 1585. These images are a unique visual record of the native inhabitants of America before colonisation truly began.

This is the first book to describe and depict native American costume, culture and society for European readers. It was published in 1590 by the enterprising merchant Theodor de Bry, who identified a market for illustrated works on travel and newly discovered lands. He made use of the text written by Thomas Harriot and published in 1588 as A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, and turned it into a Latin edition to reach a wider readership. For this edition de Bry included engraved plates based on the watercolours of English colonist John White, who worked as an artist during the pioneering attempt to settle in 1585. These images are a unique visual record of the native inhabitants of America before colonisation truly began.

This copy (shelfmark JY 601) is beautifully hand-coloured and was given to Edinburgh University Library in 1674. Although it has clearly been well-used in the past, it was quite unknown to all the current curators and has never been digitised or conserved. That will now change!

Joe Marshall, Head of Special Collections

PubMed Access Issue – Resolved

PubMed access is currently unavailable. We are investigating this access issue and will send out further information as soon as possible.

Alternative resources can be found on the Medicine A-Z list including Medline via Ovid.

Access has now been restored.

Elizabeth Wiskemann, First Woman Professor and War-Hero

A university figure that deserves far greater recognition is our first woman professor Elizabeth Wiskemann (1899-1971), who held the Montague Burton Chair of International Relations from 1958 to 1961. Although her name is absent from subsequent published histories, the University Journal for May 1958 certainly grasped the significance of her arrival. Announcing ‘the first woman to be appointed to an Edinburgh Chair’, it presented her as ‘a writer of authority on international affairs’, who had held appointments as a ‘press attaché to the British Legation at Berne, as a correspondent of The Economist at Rome, and as Director of the Carnegie Peace Endowment for Trieste’.

While these are major achievements, her personal contribution to 20th-century history ran much deeper. From 1930, Wiskemann (whose grandfather was German) worked as a political journalist in Berlin for the New Statesman and other publications, and was among the first to warn of the dangers of Nazism. So effective were her articles in alerting international readers to the true nature of Hitler’s regime that she was expelled from Germany by the Gestapo in 1937. She continued to expose Nazi plans for German expansion in her influential books Czechs and Germans (1938) and Undeclared War (1939).

Wiskemann did indeed spend the war as a press attaché in Switzerland, but this was cover for her true job of secretly gathering non-military intelligence from Germany and occupied Europe via the contacts she had made as a journalist. In May 1944, British Intelligence learned that the hitherto unknown destination to which Hungarian Jews were being deported was Auschwitz. When the allies turned down a request to bomb the railway lines (due to limited resources), Wiskemann hit on a cunning ploy. Knowing that it would be seen by Hungarian intelligence, she deliberately sent an unencrypted telegram to the Foreign Office in London. This contained the addresses of the offices and homes of the Hungarian government officials best positioned to halt the deportations and suggested that they be targeted in a bombing raid. When, quite coincidentally, several of these buildings were hit in a US raid on 2 July, the Hungarian government leapt to the conclusion that Wiskemann’s telegram had been acted upon and put an end to the deportations.

Wiskemann continued to publish on German and Italian politics after the War. She was appointed to the Edinburgh Chair on the recommendation of William Norton Medlicott (1900-1987), Professor of International History at the London School of Economics, who described her as ‘a pleasant, active, middle-aged woman’ who would ‘be a very suitable choice’. Lectures by previous holders of the Chair had been poorly attended as they formed part of no degree course. Wiskemann, however, did much to boost the profile of her post by inviting national and international experts to lead discussion groups on issues of the day. The focus of her own teaching increasingly moved away from European issues to developments in post-colonial Africa. Click on the image, right, to see a handwritten list of lectures and discussion groups for 1961.

Wiskemann continued to publish on German and Italian politics after the War. She was appointed to the Edinburgh Chair on the recommendation of William Norton Medlicott (1900-1987), Professor of International History at the London School of Economics, who described her as ‘a pleasant, active, middle-aged woman’ who would ‘be a very suitable choice’. Lectures by previous holders of the Chair had been poorly attended as they formed part of no degree course. Wiskemann, however, did much to boost the profile of her post by inviting national and international experts to lead discussion groups on issues of the day. The focus of her own teaching increasingly moved away from European issues to developments in post-colonial Africa. Click on the image, right, to see a handwritten list of lectures and discussion groups for 1961.

The Montague Burton Chair (endowed by Sir Maurice Montague Burton, founder of the men’s clothing chain) was a three-year appointment, at the end of which holders were eligible to apply for re-election. Wiskemann chose not to stand for re-election, much to the University Court’s dismay, as the Chair had proved difficult to fill. In a letter of 28 July 1960 (click right) Wickemann explained that deteriorating eyesight, exacerbated by a recent unsuccessful operation, had led to her decision. Tragically, this condition would eventually lead Wiskemann to take her own life in 1971.

The Montague Burton Chair (endowed by Sir Maurice Montague Burton, founder of the men’s clothing chain) was a three-year appointment, at the end of which holders were eligible to apply for re-election. Wiskemann chose not to stand for re-election, much to the University Court’s dismay, as the Chair had proved difficult to fill. In a letter of 28 July 1960 (click right) Wickemann explained that deteriorating eyesight, exacerbated by a recent unsuccessful operation, had led to her decision. Tragically, this condition would eventually lead Wiskemann to take her own life in 1971.

Paul Barnaby, Centre for Research Collections

Library Play Day

Last Friday, Gavin, Caroline, Matthew and I attended a Library Gamification day organised by the Scottish Academic Libraries Cooperative Training Group. Andrew Walsh, from the University of Huddersfield gave us an introduction to gamification and then gave us all a pack of Lego with the challenge to build our ideal librarian.

Last Friday, Gavin, Caroline, Matthew and I attended a Library Gamification day organised by the Scottish Academic Libraries Cooperative Training Group. Andrew Walsh, from the University of Huddersfield gave us an introduction to gamification and then gave us all a pack of Lego with the challenge to build our ideal librarian.

We then play ed different games to discover the different game mechanics we could use when building our own library games later in the day. The Lego was again utilised to form groups for the rest of the day based on common issues we wanted to address. Here’s my Lego model of a problem we face here at the University of Edinburgh, the Lego wall represents the Main Library, with the pink and red blocks being the floors most undergraduates visit and the grey floors the Lower Ground Floor, fifth and sixth floors containing the rare and unique collections that are unknown to many of our students.

ed different games to discover the different game mechanics we could use when building our own library games later in the day. The Lego was again utilised to form groups for the rest of the day based on common issues we wanted to address. Here’s my Lego model of a problem we face here at the University of Edinburgh, the Lego wall represents the Main Library, with the pink and red blocks being the floors most undergraduates visit and the grey floors the Lower Ground Floor, fifth and sixth floors containing the rare and unique collections that are unknown to many of our students.

We then created board and card games based on the common issues we face in our libraries.

The group I was in created a ca rd game called ‘Library Soup’, where each player was given a ‘recipe card’, representing an assignment that they had to complete with five visits to the Library (five turns). The player with the highest points at the end was the winner. The aim of the game was to teach the players that not all library resources are equal. As the assignment could be completed with resources with low points, e.g. a magazine article or high points e.g. a peer-reviewed article.

rd game called ‘Library Soup’, where each player was given a ‘recipe card’, representing an assignment that they had to complete with five visits to the Library (five turns). The player with the highest points at the end was the winner. The aim of the game was to teach the players that not all library resources are equal. As the assignment could be completed with resources with low points, e.g. a magazine article or high points e.g. a peer-reviewed article.

Gavin and Matthew’s team created a board game called ‘Find-It‘ to encourage users to discover resources in their University Library. Players started off at the library entrance, drew cards to see what items / resources they had to locate and then searched for these in the physical and digital library space. The game aimed to raise awareness of the diversity of library resources available while orientating students around the library building.

Gavin and Matthew’s team created a board game called ‘Find-It‘ to encourage users to discover resources in their University Library. Players started off at the library entrance, drew cards to see what items / resources they had to locate and then searched for these in the physical and digital library space. The game aimed to raise awareness of the diversity of library resources available while orientating students around the library building.

In Caroline’s teams game ‘Database Ace‘  players worked their way up the board picking up reward, risk and chance cards. The cards taught users about the use of online database in their assignments.

players worked their way up the board picking up reward, risk and chance cards. The cards taught users about the use of online database in their assignments.

Andrew, also gave us an overview of ‘Lemon Tree‘ a rewards based application developed in partnership with University of Huddersfield Library, which gives users points and badges for library activities.

Videos of all the games designed on the day are available on Andrew’s Blog .

Claire Knowles, Gavin Willshaw, Caroline Stirling and Matthew Pang

Charles Sarolea and his relief effort for Belgium during the War

RELIEF FOR BELGIUM… OFFERS OF AID FROM ALL OVER SCOTLAND

If we are to let our collections talk about the First World War, then surely the story of Charles Sarolea (1870-1953) and his efforts to aid the people of war-ruined Belgium has to be told. His wartime story emerges from the files, folders and boxes of the very large Sarolea Collection of writings and correspondence (Coll-15, Centre for Research Collections). Sarolea’s aid effort continued from the opening days of the assault on Belgium until the last months and days of the War.

Wartime propaganda… National personification of Belgium… Mother Belgium or ‘Belgica’… ‘La Belgique’… ‘La Belge’… on a Scottish booklet published by the Belgian Relief Fund. From file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15

Who was Charles Sarolea? Charles Sarolea was born on 25 October 1870 in Tongeren (Tongres) in the Belgian province of Limburg. He was educated at the Royal Atheneum in nearby Hasselt before going on to the University of Liege where he was awarded first class honours in Classics and Philosophy. In 1892 he was given a Belgian Government travelling scholarship, and between 1892 and 1894 he studied in Paris, Palermo and Naples. Still in his early 20s he became private secretary and literary adviser to Hubert Joseph Walthère Frère-Orban (1812-1896) who had been Prime Minister of Belgium (Liberal Party) between 1878 and 1884. This task brought Sarolea early initiation into wide circles of international affairs, both political and cultural. Indeed later, the Belgian Royal Family would be counted among his circle.

In 1894, at the age of 24, Charles Sarolea became the first holder of the newly-founded Lectureship in French Language and Literature and Romance Philology at Edinburgh University, and in 1918 he would become the first Professor of French when that Chair was established at the University. He held a post and Chair at the University for some 37-years, 1894-1931. From 1901, Sarolea was also the Belgian Consul in Edinburgh.

Photograph in Dr. Charles Sarolea author, lecturer, cosmopolitan in the file entitled ‘Biographical and bibliographical material relating to C. Sarolea’, in Sarolea Collection 223, Coll-15.

From 1891 until the outbreak of War in August 1914, Sarolea had written books on a wide range of international affairs and topics, including: Henrik Ibsen (1891); Essais de philosophie et de literature (1898); Les belges au Congo (1899); A Short History of the Anti-Congo Campaign (1905); The French Revolution and the Russian Revolution (1906); Newman’s Theology (1908); The Anglo-German Problem (1912); and, Count L.N. Tolstoy. His life and work (1912). From 1912 until 1917, he was also Editor of the Everyman magazine published by J. M. Dent – the magazine which features prominently in our story about Belgium.

Many other resources elsewhere can tell the in-depth military and strategic story of Belgium’s stubborn resistance during the early days of the War, but a brief foray into the Belgian experience can do no harm here in a phrase or two. Basically… the Belgian army – around a tenth the size of the German army – managed to frustrate the infamous Schlieffen Plan to capture Paris, and held up the German offensive for nearly a month giving the French and British forces time to prepare for a counter-offensive on the Marne.

The Special Belgium issue of Everyman, November 1914, contained pictures of the war-spoiled country. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

The Special Belgium issue of Everyman, November 1914, contained pictures of the war-spoiled country. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

In this opening phase of the War, many hundreds of civilian Belgians were killed, many thousands of homes were destroyed, and nearly 20% of the population escaped from the invading German army.

Destroyed house in Malines (Mechelen) in the Province of Antwerp, Belgium. From an envelope of ‘Miss Findlay’s photographs’, in the file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′, Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15.

Goodwill towards Belgian refugees and those Belgians remaining in the country was shown right across the UK, not least in the form of the Belgium Relief Fund launched by The Times, the National Committee for Relief in Belgium, and the Belgian Orphan Fund.

Circular advertising the ‘Everyman Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund’. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Also, from the very outset of War in August 1914, the Everyman magazine had established its own Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund and this was administered by the Charles Sarolea, the Belgian Consul, in Edinburgh, assisted by a Committee.

Collection envelopes issued by the National Committee for Relief in Belgium. The design showing a mother and child was by Louis Raemaekers. From a file entitled ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’, in Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

Goodwill was also registered across Scotland where a National Appeal for Belgium was opened, as this item from the Sarolea Collection shows (from file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15). The pamphlet issued by the National Appeal provided a summary of the work undertaken in Scotland where the number of Belgian refugees registered in the country in December 1915 was 13,307.

The fact that the Editor of Everyman was of Belgian origin and that he was the Belgian Consul in the capital of Scotland enabled him to be in close touch with events as they unfolded in Belgium and with the conditions of the civilian population. On 13 October 1914, as the British and French troops tried to outflank the German army – and thus establish the general shape of the Front from the Channel coast to the border with Switzerland for the next four years – Sarolea was informed by the Consul General in London (Edouard Pollet) that the legitimate Belgian government had left Ostend in Belgium for the safety of Le Havre, France.

Letter from the Belgian Embassy in London to Sarolea at the Belgian Consulate in Edinburgh indicating the removal of the Belgian government to Le Havre, France. From a file entitled ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’, in Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

As for Belgian Relief… Sarolea and the Belgian Consulate in Edinburgh received money and requests for collecting boxes and other means of formalising the collection of funds. From all across Scotland, the Consulate also received offers of hospitality and requests for cooks, kitchen-maids, laundry-workers, nursery-maids, tutors, knitter-mechanics, sewing-maids, gardeners, grooms, house-maids and other domestic servants, and ploughmen and other agricultural workers – jobs for Belgian refugees.

A list of ‘Offers of Hospitality received at the Belgian Consulate, Edinburgh’ in the file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, notified the following generous offers…: From Eyemouth came the offer for a ‘Lad as boots in hotel, permanent’, with ‘Food, travelling clothes, all offered, and 2/6 a week and all tips, say 7/6 per week’ (2/6 was one-eighth of £1 in the old currency). From North Berwick came the offer of a post as ‘Domestic servant £18, with child £12’, and from Dunblane ‘two bed-rooms, each with double beds, for superior refugees, to live with family’, and the same household would also take ‘two Belgian servants to do work and receive wages’.

Offer of help received by Sarolea at the Belgian Consulate, Edinburgh. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15.

Offer of help received by Sarolea at the Belgian Consulate, Edinburgh. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 76, Coll-15.

A household in Fife offered a placement for a ‘Mother and daughter (past school age) or two sisters as servants’, and the offer extended to ‘£24 for the two and help with their wardrobe’. From Peterhead came the offer to take ‘One little girl for an indefinite period’ and the girl could be taken ‘at once’. And, from the Kinnordy Estate, Kirriemuir came the offer of ‘Two houses’ for up to 44 ‘Cultivated and scientific people’ and this could include work.

Letter with contribution to the Fund from someone who ‘deeply feels for brave little Belgium’ and who had visited Dinant a few years earlier. Dinant had been severely damaged in the first months of the war. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Many letters from children were received with money raised in various ways – such as selling flowers from the garden or making pictures made from postage stamps – as these letters show here:

Letter from children in Balerno, 1914. In packet/envelope ‘Letters from children for possible publication’ in the file ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′. Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Second page of the letter. In packet/envelope ‘Letters from children for possible publication’ in the file ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′. Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Picture of ‘La Belge’ by a 14-year old girl from Edinburgh, and made from postage stamps, 1914. In the file ‘Letters from children for possible publication’ in the file ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund, 1914-1916′. Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Soldiers too benefited from the charitable-giving fostered by the relief effort centred on the Belgian Consulate in Edinburgh. In 1917 an appeal was raised on behalf of Belgian soldiers ‘spending their hard-earned leave in the Edinburgh district’. In a letter from the ‘Edinburgh Consular Belgian Relief Fund’ to the Editor of the Scotsman in October 1917, it was pointed out that the pay of a Belgian soldier was only just over 2d per day (around 50p at today’s levels) and that a soldier could not afford maintenance expenses while in Edinburgh. The Fund made an appeal asking for help from ‘citizens of Edinburgh who would be willing to give those soldiers hospitality or to pay for their maintenance whilst on leave’. The Fund was sure that Edinburgh’s people would help ‘those brave Belgian lads’.

Draft letter to the ‘Scotsman’, 3 October 1917, requesting help from the people of Edinburgh for Belgian soldiers on leave in the city. From the file ‘Edinburgh Consular Relief Fund 1916-1918. Correspondence’, in the wider file ‘Everyman & Edinburgh Consular Belgian Relief Funds. Correspondence & figures, 1914-1918′. Sarolea Collection 78, Coll-15.

In November 1914, Sarolea issued a Special Belgium number of the magazine, Everyman. Illustrated with Albert I, King of the Belgians, on the front cover, the issue was seen as a ‘means of making a wider appeal to the sympathy and generosity’ of readers. Sarolea claimed that from the start of the assault on Belgium in August 1914 until the Special Belgium issue, the magazine’s ‘efforts have resulted in the raising for the relief of Belgian distress and the reconstruction of Belgian prosperity the substantial sum of thirty-one thousand pounds (£31,000)’ – a colossal sum 100 years ago, the equivalent of £3-million today. Until the Everyman effort, no weekly magazine ‘has ever raised anything like so large a sum for the public cause’.

Front cover of Everyman, November 1914. From a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

The Special Belgium issue was filled with articles and photographs, with many of these describing and illustrating the destruction and suffering experienced by Belgians.

Like many contemporary journals, the Everyman Special Belgium issue contained patriotic advertisements for household shopping – drinks and sweets.

In addition to papers and correspondence specifically concerning the ‘Everyman Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund’ within the expansive Sarolea Collection, the files also contain ephemera produced by other charitable efforts. One piece is a copy of a drawing produced by Louis Raemaekers (1869-1956) the Dutch painter and editorial cartoonist for De Telegraaf, the Amsterdam daily newspaper. His drawing was used by the Belgian Orphan Fund which encouraged the contribution of sixpence to ‘Save that Child!’

Drawing by Louis Raemaekers and used by the Belgian Orphan Fund. From a file entitled ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’, in Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

Even in November 1914, those behind the Special Belgium issue of Everyman were looking ahead to the end of the War which many believed would be of short duration. A piece by the Belgian-British Reconstruction League talked of the ‘tremendous task’ ahead. ‘A whole country will have to be reclaimed from devastation. A whole people will have to be repatriated and resettled’. As the War ground on though, Sarolea travelled extensively during 1914 and 1916 – across France and to Switzerland and Italy – as his passport shows.

Passport issued in December 1914 to Charles Sarolea, naturalised British subject of Belgian origin, travelling to France… but not valid for travel in Army zones. In the file entitled ‘C.S. personal documents, Passport etc’. Sarolea Collection 222, Coll-15.

The ‘Everyman Belgian Relief and Reconstruction Fund’ was wound up towards the end of 1917, and real reconstruction across Belgium would be well underway by the early 1920s. By the end of the war, some 200,000 Belgians had sought refuge across the UK – 17,000 in the Glasgow area alone – and around £6-million to £7-million had been contributed to all of the Belgian charities (circa £400-million today), and these figures were used by Sarolea in his defensive ‘open letter’ to an English correspondent who had criticised the effort.

Sarolea defended charitable giving to Belgians in this ‘open letter’ written in May 1917. From the file ‘Belgian Consular Correspondence, 1915-1919’. Sarolea Collection 73, Coll-15.

Immediately after the War, in March 1919, in Edinburgh, Charles Sarolea was presented with an illuminated scroll by grateful Belgians honouring his wartime work for aid to Belgium. Heading the signatures on the scroll was that of the Rev. O. M. Couttenier a Belgian priest in Edinburgh.

Professor Charles Sarolea resigned his Chair in 1931 but continued to reside in Edinburgh and remained as Belgian Consul in the city until his death in 1953. In 1954, his papers and correspondence were purchased for Edinburgh University Library.

Detail from the front cover of Everyman, November 1914. In a file entitled ‘Everyman Belgian Relief Fund 1914-1916′, in Sarolea Collection 77, Coll-15.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

Thomas Nelson Exhibition: Covers in Colour

The new exhibition in the CRC showcases a number of items from the Thomas Nelson Archive, which has been written about on this blog more than once in the past. It really is an interesting collection and it’s great to see some of the books making it into the public eye.

Fiona Mowat and Beth Dumas, who began organising and cataloguing the collection of over 10,000 books, have worked with Emma Smith to make this exhibition possible. In it you can see a range of books from throughout the 20th century including stylish art deco designs and pulpy dust-jackets from the ‘40s and ‘50s. There is plenty of sci-fi and and romance present for genre fans!

The exhibition can be seen at the Binks Trust Display Wall at the Centre for Research Collections on the 6th floor of the Main Library from 3 March until 21 May 2015.

More information can be found here:

Read more about the Thomas Nelson Archive at the Library Annexe here:

[Blog] Fiona an Beth blog about their work on the Thomas Nelson collection

[Blog] The AnneXe Factor: Full Nelson Archive

Carl Jones, Library Annexe Supervisor

EPSRC Expectations Awareness Survey

As many of you will already know EPSRC set out its research data management (RDM) expectations for institutions in receipt of EPSRC grant funding in May 2011, this included the development of an institutional ‘Roadmap’. EPSRC assessment of compliance with these expectations will begin on 1 May 2015 for research outputs published on or after that date.

In order to comply with EPSRC expectations and to implement the University’s RDM Policy, the University of Edinburgh has invested significantly in RDM services, infrastructure (incl. storage and security) and support as detailed in the University of Edinburgh’s RDM Roadmap.

In an effort to gauge the University of Edinburgh’s ‘readiness’ in relation to EPSRC’s RDM expectations, we are conducting a short survey of EPSRC grant holders.

The survey aims to find out more about researcher awareness of those expectations concerning the management and provision of access to EPSRC-funded research data as detailed in the EPSRC Policy Framework on Research Data.

We aim to conduct follow-up interviews with EPSRC grant holders who are willing to talk through these issues in a bit more detail to help shape the development of the RDM services at the University of Edinburgh.

We will endeavour to make available some of our findings shortly. In the meantime, if you want to use or refer to our survey we have posted a ‘demo’version below:

https://edinburgh.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/epsrc-expectations-awareness-demo

Should you decide to make use of our survey, let us know, as we can potentially share our data with each other to benchmark our progress.

(As an aside Oxford University have crafted a useful data decision tree for EPSRC-funded researchers at Oxford)

Regards

Stuart Macdonald

RDM Services Coordinator

stuart.macdonald@ed.ac.uk

Upadate: A link to the findings can be found at: https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/datablog/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/EPSRC-RDM-Expectations-Awareness-Survey-Findings.pdf

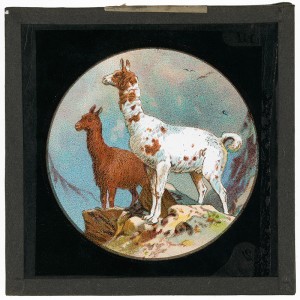

Science on a Plate: an evolution

I have been based in the Digital Imaging Unit, digitising the Roslin Glass Plate Slide Collection, since October last year as part of the ‘Science on a Plate’ project, funded by the Wellcome Trust’s Research Resources scheme. Recently, I became intrigued by the history of the glass plate slide itself so I decided to carry out a little research of my own.

Curious to discover where glass plate slides are positioned on the timeline of photography; what chemistry and techniques were involved in their making; and the role they played, I began with searching online and delving into some books on the history of photography.

The slides in the Roslin Collection date, loosely, between the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. This leads me to think that the majority of the slides are dry plate, gelatin-coated, slides as this was the most popular process used during that time period. Other processes, however, may have also crept in to the collection because different techniques and methods may have overlapped.

The slides are all positive, transparent images, with the nature of the images spanning; documentary photography, maps, statistics, instructions, illustrations, portraits, images taken from publications… the list goes on. Physically, the slides are all 3×3 inches in width and diameter, with a depth of roughly 3-6 millimetres. There are 3465 of them!

To give a little context, these slides might also be referred to as lantern slides. This is a term that relates to the fact that, early on, magic lanterns would be used to project similar looking slides. Magic Lantern (and Sciopticon) projectors had been used long before the invention of photography to project images painted on glass.

It was not until 1840 that the inventors of the daguerreotype began using magic lantern projectors in an attempt to project their photographic images for better viewing. The dull and foggy nature of the daguerreotype, however, did not lend itself well to the projection of light.

Next came the creation of the wet plate negative in 1851 by the Englishman, Frederick Scott Archer. This process involved coating glass plates with a collodian chemical and exposing light onto the glass while the chemical was still wet. This allowed for shorter exposure times when taking photographs. Previously, daguerreotypes (1839-1850’s) and calotypes (1841-1850’s) would require long exposures, often over one minute, forcing those being photographed to remain still in order to avoid blurring within the image. This is why daguerreotypes and calotypes often look posed and overly considered as compositions.

Accordingly, the colllodian wet plates gave a bit more flexibility when composing photographs. If, however, using the wet glass plate outwith the studio, photographers would have been required to carry processing chemicals and a portable darkroom as the wet plates would need developing immediately after exposure.

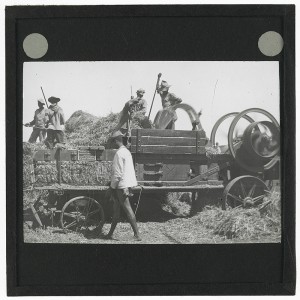

Photography remained a rather laborious procedure until the invention of the dry plate slide. In 1871, Richard Leach Maddox discovered that coating glass with silver bromide within a layer of gelatin would give more efficient photographic results; speedier and with a longer shelf life. The burden of hauling around chemicals and a darkroom was removed because the developing could be done at a later date by a specialist. In light of this photography became more accessible, opening up the practice to amateur photographers. Only the camera (camera models were becoming smaller and more portable over time) and the dry plates themselves were needed. Dry glass plates could be produced on mass, ready to use on the job. The act of taking a photograph therefore became less time-consuming, causing a change in the style of photographs being produced. This can be seen in the Roslin Glass Plate Slide Collection. On viewing many of the slides the camera seems to be there as a spectator, very much in the moment, giving the viewer a sense of what it mean to ‘be there’ – a relatively new phenomenon.

Roslin glass slide. A street hawker with his horse drawn cart standing next to a couple of children in Buenos Aires, Argentina in the late 19th or early 20th century.

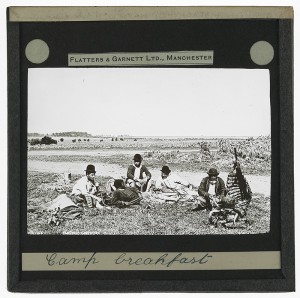

Roslin glass slide. A group of men eating breakfast in their camp on the plains in [Argentina or Uruguay] in the early 20th century.

Of all the various glass plate processes, the dry, gelatin-based plate had the longest run of success. It was not until the 1930’s when it was reduced to history with the introduction of nitrate film negatives and, namely the 35mm Kodachrome.

These slides were catalogued as part of the ‘Towards Dolly’ project and the Roslin Slide Collection can be viewed here.

Some useful reading:

Frizot, Michel, The New History of Photography (1994), Chapter 5

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/landscape/lanternhistory.html

http://archives.syr.edu/exhibits/glassplate_about.html

http://www.nfsa.gov.au/research/papers/2012/05/10/preserving-20th-century-glass-cinema-slides/

John

Project Photographer: Science on a Plate.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....