Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 14, 2025

Talk given to Members of the South Georgia Association – on the Salvesen Archive

AT THE BUDONGO LECTURE THEATRE, EDINBURGH ZOO, SATURDAY 31 OCTOBER 2015

This past weekend – Saturday 31 October – saw Dr. Graeme D. Eddie of the Centre for Research Collections (CRC) participate in the Penguin City Meeting of the South Georgia Association (SGA), held at the Budongo Lecture Theatre, Edinburgh Zoo. The SGA is a non-profit organisation formed to give voice to those who care for South Georgia, a remote mountainous island in the South Atlantic.

The SGA meeting had been organised and chaired by Dr. Bruce F. Mair, geologist. Also present among the geologists, glaciologists, botanists, ecologists, and former whalers, were Alexandra Shackleton, granddaughter of Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) and current President of the James Caird Society, descendants of Carl Anton Larsen (1860-1924) the Norwegian-British Antarctic explorer, and descendants of Sir James Mann Wordie (1889-1962) the Scottish Polar explorer and geologist.

The SGA meeting had been organised and chaired by Dr. Bruce F. Mair, geologist. Also present among the geologists, glaciologists, botanists, ecologists, and former whalers, were Alexandra Shackleton, granddaughter of Sir Ernest Shackleton (1874-1922) and current President of the James Caird Society, descendants of Carl Anton Larsen (1860-1924) the Norwegian-British Antarctic explorer, and descendants of Sir James Mann Wordie (1889-1962) the Scottish Polar explorer and geologist.

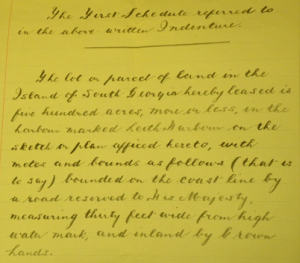

Signature of William Lamond Allardyce, Governor and Commander in Chief of the Falkland Islands, together with Seal, on the Lease agreed with the South Georgia Co., a firm raised by Christian Salvesen & Co. in 1909… an item in the Salvesen Archive.

Presentations on the day covered ‘Accessible Archives and the Industrial Past’, ‘Science and Field Work’ and ‘South Georgia 2015 and Beyond’ and, represented as an accessible archive, the CRC presentation was given in the first section of the Meeting.

The Lease indicated that ‘five hundred acres, more or less, in the harbour marked Leith Harbour’, South Georgia, was to be allocated to the firm. The Lease permitted the firm to operate two whale-catcher vessels in addition to two associated with a Lease over Allardyce Harbour. Four vessels in the region made the whaling operation viable.

Profiling the Salvesen Archive, it offered a brief history of the firm of Christian Salvesen & Co. Ltd., and a look at the transfer in three stages of the archive of the company’s whaling business to Edinburgh University Library starting in 1969.

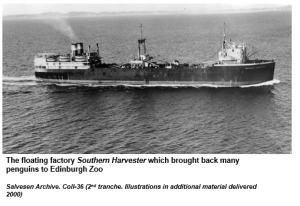

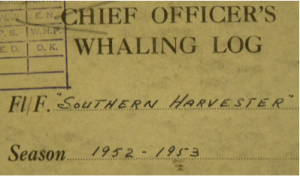

Cover of the ‘Whaling Log’ of the Salvesen & Co. whale factory-ship, ‘Southern Harvester’, season 1952-1953… an item in the Salvesen Archive.

The content of the Salvesen Archive was described with illustrations showing its variety. The talk looked at some of the conservation needs of the material, the use of the collection by researchers, and offered glimpses of the lives of personnel at the South Georgia stations.

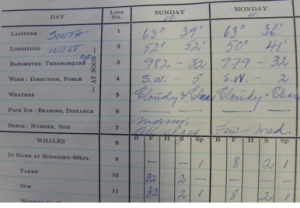

While the ‘Whaling log’ has provided data of whales caught and processed to researchers of the past, it also provides climatological information to weather scientists and researchers today, giving information about ice, wind, and temperatures.

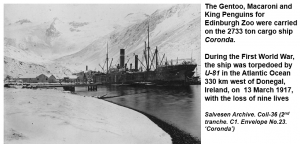

The transport of live penguins by the company to Europe – not least to Edinburgh Zoo – was also briefly explored through images from the Salvesen Archive.

The SGA meeting also saw presentations from the National Library of Scotland with the title ‘South Georgia on the Shelf’ and looking at the Map and Wordie collections, and from the South Georgia Heritage Trust & the National Museums of Scotland about a project to highlight the location of South Georgia related objects around the world. John Alexander who had spent winter seasons in the whaling industry gave a talk on ‘Sailing in the Antarctic with Salvesen’.

There were also presentations on tussock grass on South Georgia, the geology of the island, sustainable South Georgia fisheries management, and the rat eradication programme. The day was concluded with a visit to the penguin enclosure at Edinburgh Zoo.

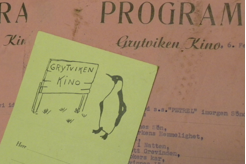

‘Membership card’ for the Grytviken Kino… the cinema at the Grytviken whaling station, South Georgia. At the time – up to the early 1960s – it was the most southerly cinema in the world after the cinema in Ushaia, Tierra del Fuego.

The host for SGA Meeting, Dr. Bruce F. Mair had been a geologist with the British Antarctic Survey and had carried out extensive mapping in an area of South Georgia around Brandt Cove, Larsen Harbour and Drygalski Fjord in the 1974-75 and 1976-77 field seasons. The region’s Mt. Mair is named after him!

Centre for Research Collections, Edinburgh University Library, 2 November 2015

Database trials for Chinese studies

We have been offered a free trial of the following e-resources for Chinese studies:

Access on the University network or off campus via VPN. Trial ends: 29 November

Access on the University network or off campus via VPN. Trial ends: 13 November. This resource is listed on our trials webpage and Discovered.

Pishu (皮书) refers to official white paper, blue paper or green paper policy documents in China. They offer candid, in-depth policy recommendations on topics including climate change, social responsibility, the economy, energy conservation, food/drug safety, health care, human rights, international development, and rule of law, regional security, and women’s rights. The database contains the full text of over 1,000 such books in Chinese and are full-text searchable.

A title list of volumes included in PISHU is also available here: http://www.eastview.com/online/ebooktitles

- 大成古纸堆 (including 申報)

Access on the University network or off campus via VPN. Trial ends: till further notice.

This resource contains the following sections:

老旧刊 (containing hundreds of full-text periodicals from the late Qing Dynasty to 1949. There are many titles that are not found in the Late Qing Periodicals 1833-1911 and Minguo periodicals 1911-1949 that we subscribe to.)

民国丛书 (books published between 1911 and 1949)

申报 (most important Chinese newspaper published between 1872 and 1949)

古方志集 (hundreds of historical local gazetteers)

古籍文献 (thousands of Chinese classics and rare books)

中共党史期刊数据库 (full-text periodicals published by the Chinese Communist Party before 1949)

顺天时报 (1907-1930)

- 四库全书存目丛书

On Chinamaxx database platform. Trial ends: till further notice

- 地方志

On Chinamaxx database platform. Trial ends: till further notice

Feedback can be sent to shenxiao.tong@ed.ac.uk

Hybrid open access revenue

Photo courtesy of Images_of_Money

Over the last few weeks I’ve been preparing and reviewing various compliance and financial reports for funding agencies on their annual open access block grants awarded to our institution. One of the benefits of having sets of large data in front of you is that you start seeing trends and think of mildly* interesting things to do with it.

(* I say mildly because “The best thing to do with your data will be thought of by someone else“, which is one of the many reasons it is important to make your data open.)

Sequentially issued invoices

One of the things I’ve noticed is that one of the larger publishers (Elsevier) issues sequential invoices of the form W1234567 and 12345CV0. If we had enough invoices spread over a reasonable period of time we could estimate what their hybrid open access revenue is during that time period, and potentially extrapolate further. Just to be clear I’ve only picked Elsevier because they are the publisher that we have gathered the most information about open access expenditure due to their large market share.

Invoices issued from the European office

I looked through our admin records and noted invoice # W1274177 was issued on 30 April 2015 whilst invoice # W1300445 was issued on 22 October 2015. During this 175 day period there appears to be 26,268 invoices issued by the publishers European Corporate Office, which works out at about 150 APCs per day for their portfolio of hybrid journals.

Our average APC in 2014/15 (n=65) for this publisher is £2066.81 so their revenue for this period was in the region of £54,290,965, or an APC daily revenue of £310,234.

Invoices issued from the North American office

The publishers also issues invoices of the form 12345CV0 from their North American Corporate Office. Noting that invoice 11795CV1 was issued on 19th May 2015 and invoice 12306CV0 was issued on 15th October 2015 this suggests that 511 APCs were charged over the 149 day period, or around 3 APCs per day.

Using the same average APC (£2066.81) as before this gives us an estimate revenue of £1,056,140 during the time period, or £7,088 per day.

Note that the invoices issued from the regional offices do not reflect the revenue generated in that geographical area.

Global APC revenue

The combined daily APC revenue from the European and North American offices is in the region of £317,322. If we upscale this to a full year we can infer an annual APC revenue in the region of £115,822,530. This sounds like a hell of a lot of money, but put into perspective against the company’s total 2014 revenue of £5,773M (figure from the RELX Group annual report) this represents only 2% of their business income.

Assumptions

These are rough and ready calculations and should be taken with a pinch of salt because I make a number of assumptions including:

- The invoices really are sequentially issued

- No other types of transactions (e.g. journal subscriptions) are included in the invoicing sequence

- We have large enough data set to infer an annual revenue

- Daily APC rate is a good enough estimate

UPDATE

Stuart Lawson pointed out on Twitter that this estimate is likely to be on the high side:

Maritime difficulties during the First World War – Christian Salvesen & Co.

SINKINGS AND LOSS OF LIFE, SHORTAGES OF SUPPLY, AND REQUISITIONING… DIFFICULTIES FACED BY THE FIRM OF CHRISTIAN SALVESEN & CO. DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR

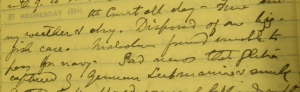

![]() Contemporary papers within the archive of the general shipping and whaling firm Christian Salvesen & Co. (Coll-36) – based in Leith, Scotland, until the late 20th century – tell of the company’s trials during the First World War. Indeed, diary entries of both Edward Theodore Salvesen (Lord Salvesen) (1857-1942) and a younger brother Theodore Emil Salvesen (1863-1942) record the loss of the Salvesen vessel Glitra which was the first British ship to be sunk through enemy action by a submarine in the opening months of the First World War. Glitra had been sunk by a German submarine on 20 October 1914, just off Skudenes, Rogaland, Norway.

Contemporary papers within the archive of the general shipping and whaling firm Christian Salvesen & Co. (Coll-36) – based in Leith, Scotland, until the late 20th century – tell of the company’s trials during the First World War. Indeed, diary entries of both Edward Theodore Salvesen (Lord Salvesen) (1857-1942) and a younger brother Theodore Emil Salvesen (1863-1942) record the loss of the Salvesen vessel Glitra which was the first British ship to be sunk through enemy action by a submarine in the opening months of the First World War. Glitra had been sunk by a German submarine on 20 October 1914, just off Skudenes, Rogaland, Norway.

The Salvesen vessel ‘Glitra’ scuttled by its German captors off Skudenes, Norway 20 October 1914. Coll-36 (2nd tranche, C1. No.41).

Glitra had started life as the Saxon Prince at the Swan Hunter yard on the Tyne (Wallsend) where it was launched in 1882. It sailed with the Prince Steam Shipping Co. until 1895 when it was acquired by Christian Salvesen & Co. and renamed Glitra. During a voyage from Grangemouth to Stavanger in Norway, carrying coal, iron plate and oil, the ship was stopped and searched 26 km off Skudenes – just outside neutral Norwegian territorial waters – by the German U-boat U-17 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Johannes Feldkirchner.

Diary entry of Lord Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Glitra’ in October 1914. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Lord Salvesen, F17).

No lives were lost during the incident however, as the crew of the Glitra had been ordered into lifeboats . The German sailors then opened the ship’s sea-valves and scuttled it. After U-17 left the scene, the torpedo boat Hai of the Royal Norwegian Navy took the lifeboats under tow to the Norwegian harbour of Skudeneshavn. The same U-boat, U-17, captured and sunk the Salvesen vessel Ailsa just north-east of Bell Rock in the North Sea on 17 June 1915.

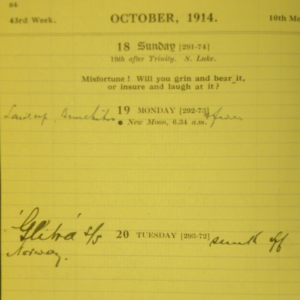

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Glitra’ in October 1914. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

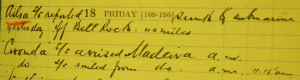

The Glitra incident was recorded in the diaries of both Lord Salvesen and Theodore Emil Salvesen. About the loss, the elder Salvesen brother wrote on Wednesday 21 October 1914, ‘Sad news that Glitra captured by German submarine & sunk’. The younger Salvesen – perhaps still recovering from the bout of bronchitis which he also noted in his diary – wrote his own stark and matter-of-fact entry on Tuesday 20 October, ‘Glitra S/S sunk off Norway’, and about the loss of Ailsa in 1915 his diary entry for Friday 18 June 1915 has ‘Ailsa S/S reported sunk by submarine yesterday off Bell Rock. 40 miles’.

The Salvesen cargo ship ‘Coronda’ torpedoed by German submarine ‘U-81’ in the Atlantic Ocean 200 miles off Ireland, 13 March 1917. Coll-36 (2nd tranche, C1. No.41).

Although the scuttling of the Glitra was the first instance of a British merchant vessel being lost to a German submarine, Salvesen would face the loss of several other vessels from its general cargo fleet during the First World War, not least the 2733 ton cargo ship Coronda which was torpedoed by U-81 in the Atlantic Ocean 330 km west of Donegal, Ireland, on 13 March 1917, with the loss of nine lives. Again, the incident was recorded in briefest terms by Theodore Emil Salvesen in his diary, ‘Coronda S/S sunk by torpedo, 200 miles from land, 9 men lost – 6.30am’. The names of some of the lost Salvesen ships – e.g. Glitra, Ailsa and Coronda – would be preserved in newer vessels a few years later.

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Ailsa’ in June 1915. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen noting the loss of ‘Coronda’ in March 1917. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

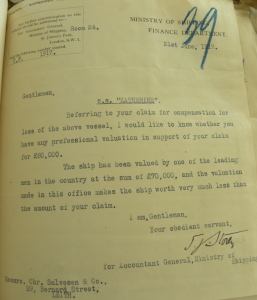

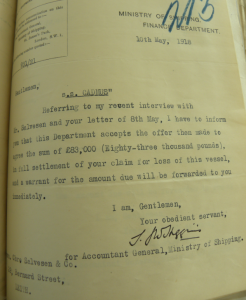

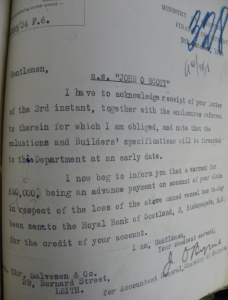

A little earlier, in February 1917, the Salvesen vessel Katherine was captured and sunk by the German merchant raider SMS Möwe . A letter from the Finance Department of the Ministry of Shipping in London to Christian Salvesen & Co. in Leith, dated 21 June 1917, reveals that the Government department was unwilling to accept the claim of £80,000 placed before them by the firm for their loss and sought ‘professional valuation in support’ of the claim. The letter stated that the vessel ‘has been valued by one of the leading men in the country at the sum of £70,000, and the valuation made in this office makes the ship worth very much less than the amount of your claim’. Later, in July 1917, the Ministry of Shipping would offer £75,000 to the firm. In March 1918 there would be further objection from the Ministry over the claim placed by Christian Salvesen & Co. for the loss of the vessel Cadmus which had been torpedoed and sunk off Flamborough Head in October 1917 by the German mine-laying submarine UC-47. The Ministry would eventually agree the sum of £83,000 in full settlement of the firm’s claim for the loss of Cadmus, and in November 1918 the Ministry agreed to pay £40,000 to Salvesen for the loss of the John O. Scott which had been torpedoed and sunk off Trevose Head, Cornwall, in September 1918 by the German mine-laying submarine U-117.

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 21 June 1917, about the firm’s claim for the loss of the vessel ‘Katherine’ through enemy action. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 10 May 1918, about the firm’s claim for the loss of the vessel ‘Cadmus’ through enemy action. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 4 November 1918, about the firm’s claim for the loss of the vessel ‘John O. Scott’ through enemy action. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

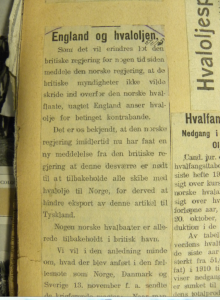

In spite of the loss of cargo vessel tonnage, the other arm of the company’s business – whaling in the South Atlantic around South Georgia – expanded further to supply much needed whale oil for the home front. The oil was required to make glycerol for the manufacture of nitro-glycerine for explosives. Whale oil was also used for the production of edible fat. To all nations – whaling or non-whaling, belligerent or neutral – the commodity was a vital one. Indeed, recorded in a collection of newspaper-cuttings within the archive of Christian Salvesen & Co. is a small article reporting a protest from Norway over the impounding of Norwegian ships and whale-oil cargo in British ports… clearly breaches of the country’s neutrality by Britain. The article reports how previously the British authorities had notified Norway that they would respect the Norwegian whaling fleet, except in cases where it was believed the cargo was being supplied to Germany. Now however, the article continues, the Norwegian government had received a new message from the British government indicating that it was forced to impound all Norwegian ships with whale-oil cargoes to prevent export to Germany. Some Norwegian ships had already been impounded. The article goes on to remind the British governement of the rights of neutral states such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden to onward transport of cargoes and free navigation.

Article, ‘England og hvaloljen’, dated 5 January 1915, from Norwegian title (unknown) reporting change in British policy towards Norwegian ships and cargoes. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, News-cutting Album, H27).

To increase whale oil production as the War continued, all regulations around the whaling-industry were relaxed including restrictions on the number of whale-catching vessels. Nevertheless, shortages at home in the northern hemisphere due to the war economy, and loss of the island nation’s valuable imports and exports through enemy action, affected the firm’s activities in the southern hemisphere, and the supply to it of the necessary resources to maintain its operations. Indeed, everything from fuel oils and coal, prefabricated buildings, machine tools, wires and cables, tanks, saws and saw blades, timber and wood products, and food provisions all had to be sourced beyond South Georgia and the Falkland Islands.

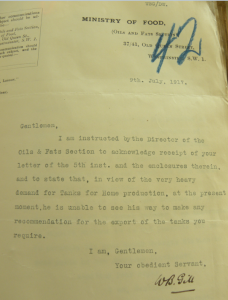

Letter from the Ministry of Food, Oils and Fats Section, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 9 July 1917, about the export of tanks. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

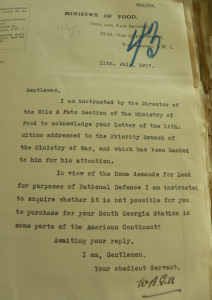

The UK was often unable to supply the resources. On 9 July 1917, the Oils and Fats Section of the Ministry of Food wrote to Christian Salvesen & Co. stating that ‘in view of the very heavy demand for Tanks for Home production’ the Director was ‘unable to see his way to make any recommendation for the export of the tanks’ required. A couple of days later, on 11 July 1917, the same Oils and Fats Section at the Ministry of Food wrote that ‘In view of Home demands for Lead for purposes of National Defence I am instructed to enquire whether it is not possible for you to purchase for your South Georgia Station in some parts of the American Continent?’

Letter from the Ministry of Food, Oils and Fats Section, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 11 July 1917, about lead and the possibility of obtaining the resource from the Americas. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

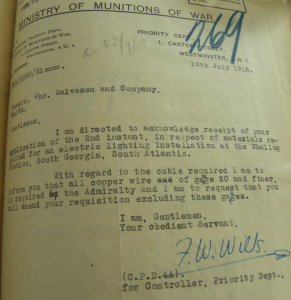

Again, on 19 July 1918, but this time from the Ministry of Munitions of War, came a letter to Christian Salvesen & Co. acknowledging receipt of an application ‘in respect of materials required for an electric lighting installation at the Whaling Station, South Georgia’. With regard to the cabling required, the Ministry wrote that ‘all copper wire of gauge 20 and finer, is required by the Admiralty’.

Letter from the Ministry of Munitions of War, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 19 July 1918, about Admiralty expropriation of copper wire of gauge 20 and finer. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Although there was a demand for whale-oil throughout the War (for glycerol and the subsequent manufacture of nitro-glycerine for explosives), it is clear that shortages of equipment and government restrictions were making it extremely difficult for the firm to meet the demand. Indeed, plans to increase the number of steam-powered whale-catching vessels operating in the Southern Ocean had to be abandoned.

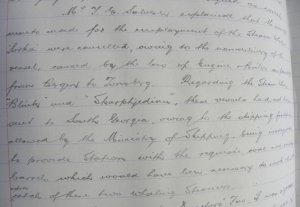

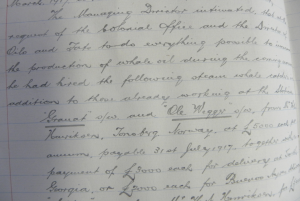

Extract from the Minutes of a Meeting of Directors (South Georgia Co. Ltd) held Thursday 26 July 1917 in Leith, and during which hiring of additional steam-powered whale-catchers was discussed. Coll-36 (3rd tranche, Minute Book, South Georgia Co. Ltd).

At a meeting of Salvesen Directors (The South Georgia Company Ltd) held at the Registered Office in Bernard Street, Leith, on 26 July 1917, it was agreed that in order ‘to do everything possible to increase the production of whale oil during the coming season’ the vessels Granat, Ole Wegger, and Sorka would be hired from Norway, and Blink and Skarphjedinn from Cape Town. In the event, Sorka had to be retained in Norway because of local losses of tonnage, and neither the vessel Blink nor Skarphjedinn could be sent south because restrictions put in place by the Ministry of Shipping meant that the station there could not be provided ‘with the requisite coal and empty barrels which would have been necessary to work up the extra catch of these whaling steamers’.

Extract from the Minutes of a Meeting of Directors (South Georgia Co. Ltd) held Friday 21 June 1918 in Leith, and during which failure to hire additional steam-powered whale-catchers was discussed. Coll-36 (3rd tranche, Minute Book, South Georgia Co. Ltd).

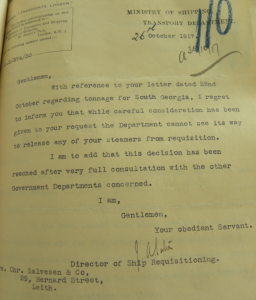

Like other shipping firms in ports around the UK, Christian Salvesen & Co. had many of its vessels requisitioned by the Government – and subsequently sunk by the Germans. This of course impacted on its South Georgia operations and its own means of supplying and maintaining these operations. A letter from the Director of Ship Requisitioning at the Transport Department of the Ministry of Shipping in London, dated 26 October 1917, records the firm’s anxieties about requisitioning. The letter in reply states that ‘regarding tonnage for South Georgia, I regret to inform you that while careful consideration has been given to your request the Department cannot see its way to release any of your steamers from requisition’.

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 26 October 1917, about a request for the release of vessels from requisition. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

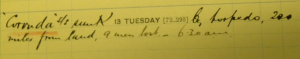

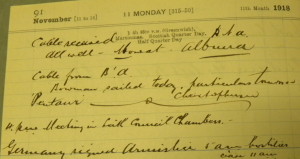

At 5am on the morning of Monday 11 November 1918 – as noted in the diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen – Germany signed the Armistice agreement, and hostilities were to cease at 11am. The slaughter of the Great War was over.

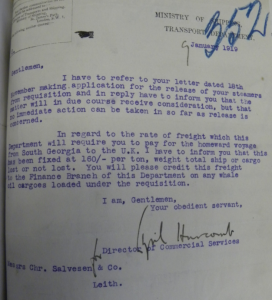

In January 1919, some two months after the Armistice, the office of the Director of Commercial Services at the Ministry of Shipping wrote to Christian Salvesen & Co. about the firm’s ‘application for the release’ of its steamers from requisition. This matter, wrote the Ministry, ‘will in due course receive consideration’, but ‘no immediate action can be taken in so far as release is concerned’.

Letter from the Ministry of Shipping, to Christian Salvesen & Co., dated 9 January 1919, about the release of vessels from requisition. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Letter book, A77).

Following the War came Peace and the firm of Christian Salvesen & Co. took advantage of the increased demand – and of course high prices – for ships and sold off a large part of its fleet. This would help keep the company afloat during the years of economic crisis that would come in the late-1920s and into the 1930s.

Diary entry of Theodore Emil Salvesen for Monday 11 November 1918, noting the Armistice. Salvesen Archive. Coll-36 (1st tranche, Diaries of Theodore Emil Salvesen, F42).

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

In addition to material in the Archive itself, and on-line maritime wreck sites, the following work was used in the construction of the blogpost: Salvesen of Leith, by Wray Vamplew (Scottish Academic Press: Edinburgh, London, 1975)

Edinburgh DataShare receives ‘Data Seal of Approval’

Earlier this week DataShare received the Data Seal of Approval – a peer review certification for trusted digital repository (TDR) status. The award is reviewed every two-years.

Edinburgh DataShare self-assessment statements for each of the 16 metrics (which express roles and responsibilities of data producer, data repository and data consumer) can be viewed on the DSA website at: https://assessment.datasealofapproval.org/assessment_175/seal/pdf/ (note: liberal use of white space). We aim to publish the actual seal on the home page of DataShare as part of the upcoming major release (2.0).

For more information about DSA see our web page, http://www.ed.ac.uk/information-services/research-support/data-library/data-repository/trustworthiness

Note: a paper will be published in the forthcoming IASSIST Quarterly showcasing institutional implementations of DSA. This follows on from a successful panel session at the IASSIST Conference at Univ. Minneapolis in June (see: http://iassist2015.pop.umn.edu/program/block6#a4)

DSA are also currently in discussion with ICSU World Data System to produce a harmonised discipline-agnostic self-assessment TDR certification scheme. This should be in place some time in 2016.

Stuart Macdonald

Associate Data Librarian

Finding Deaf Lives in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland, 1791-1845

‘As recently as the 1970s, deaf history did not exist,’ writes John Vickery Van Cleve (Deaf History Unveiled, 2002), pointing out how, until recently, the history of deaf people and their lives had been overlooked as a viable area of study. Such neglect is a shame, because deaf history can be fascinating. What it encompasses is as varied as the different degrees of hearing loss; the word ‘deaf’ can be applied to every point on the audiological spectrum between mildly hard-of-hearing and profoundly deaf, and the experience of someone who was deafened in old age (and who has participated in majority ‘hearing’ culture all their lives) is entirely different to that of a person born completely deaf. While the former almost certainly experiences hearing loss as a loss, the latter may not see their deafness that way – it hasn’t been lost, since it was never there in the first case. Deaf people for whom speech is inaccessible are also more likely to use a sign language, which, as languages which have developed naturally in deaf communities across the world, are grammatically distinct from (but as complex as) spoken languages.[1] The lives of these deaf people and their communities are particularly absent from the historical record: sign languages are minority languages with no written form and thus no primary source material exists before the invention of film. There are few accounts written in English by deaf people themselves, as formal deaf education only began in Britain in 1760 and very few deaf children received an education until the mid-19th century. So-called ‘deaf and dumb’ or ‘deaf-mute’ people were typically pitied, disparaged or simply overlooked, and so deaf people were seldom written about by (hearing) record keepers in any detail, if at all. It is, Van Cleve continues, ‘as though the world in which deaf people grew up, married, worked, procreated, and educated their children was somehow unrelated to the larger world inhabited by people who hear.’ Trying to find evidence of deaf lives throughout history, and especially before the second half of the 19th century, can be a challenge; as with the histories of other minorities, we often have to seek tantalising details hidden in the historical record and extrapolate a wider picture from these.

It was in this vein that the Old (First) and New (Second) Statistical Accounts of Scotland came to mind. For the last five years, I have taught on a course at the University of Edinburgh where the Statistical Accounts form the basis of the students’ written assessment – and, as my students will testify, my enthusiasm for the Accounts and the nuggets of localised social history they contain is, if anything, growing in intensity. So when I became interested in sign languages and the history of deaf communities, I immediately wondered whether there were any mentions of local deaf people in the Old and the New Accounts; thanks to the ‘search all text’ function, I was able to find them. There weren’t very many: out of 938 parishes, only four in the Old Statistical Account of 1791-99 (OSA) and 67 in the New Statistical Account of 1834-45 (NSA) mention ‘deaf and dumb’ people. Nor were these mentions very detailed: most merely state the number living in the parish, sometimes lumped in with other so-called ‘unfortunate’ demographics, as in the parish of Kilbarchan, Renfrewshire, which claimed seven ‘insane, fatuous, blind, deaf, dumb’ (NSA). Yet throughout the Accounts there are small glimpses of deaf lives that provide a useful springboard from which to investigate and piece together deaf history in the 18th and 19th centuries.

‘Dumbie House where Thomas Braidwood established the first school for deaf children, ‘Braidwood’s Academy for The Deaf and Dumb’ in 1760: By courtesy of Edinburgh City Libraries’

One example from the OSA comes from the parish of Aberdalgie in Perthshire. The minister writes that the local schoolmaster, Mr Peddie, had ‘acquired without any instructor, the rare talent of communicating knowledge to the deaf and dumb’ and had been teaching one ‘deaf and dumb’ boy from the parish. The boy had ‘never had another teacher’ – unsurprisingly, since the first school for the deaf, Thomas Braidwood’s Academy for the Deaf and Dumb (established in Edinburgh in 1760), had moved to London in 1783; there would be no other deaf school in Scotland before the Edinburgh Institution for the Deaf and Dumb was established in 1810. The solution in Aberdalgie appears to have worked well: Mr Peddie is described in glowing terms, and the young boy ‘has made a very great proficiency under him’ and ‘can read, write, and solve any question in the common rules of arithmetic, as well as most boys of his age who do not labour under his disadvantages.’

Education also features in the NSA. The Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Glasgow Institutions for the Deaf and Dumb were established early in the 19th century, yet these schools were expensive and over-subscribed. In the parish of Dunfermline in Fife, Rev. Peter Chalmers wrote in the NSA that, having been unable to raise enough money to send local deaf children to one of the Institutions, he had organised an ‘experiment’ in a local school:

A few years ago, four or five deaf and dumb children, belonging to the parish, were taught in Rolland School for two years and a half, by a deaf and dumb young woman … who had previously received a good education in the Edinburgh Institution.

Whereas it was (and is) often assumed that deaf education must be conducted by non-deaf tutors, Chalmers’ experiment had a young woman, Janet Robb, running an early prototype of a deaf unit in a mainstream school, working alongside but separately from the school’s main, hearing teacher of the non-deaf pupils. Although Chalmers’ experiment did not last long due to a lack of books and resources, he describes it as ‘succeed[ing] far beyond his expectations’, and declares himself convinced of the ‘entire practicability of the deaf and dumb teaching others.’ Chalmers was later able to send some of the children to the Glasgow Institution where they ‘made very rapid progress in their farther education, and in religious knowledge and character.’ Furthermore, in his self-authored, two-volume Historical and Statistical Account of Dunfermline (1844-1859), he claims that the Rolland School experiment directly inspired Edinburgh’s Deaf and Dumb Day School, which was established in 1836 by a deaf, sign language-using teacher, Alexander Drysdale, and catered to poorer children than could attend the Edinburgh Institution. Drysdale and Janet Robb had been schoolmates, and Chalmers reports that she and some of her pupils were invited to visit the fledgling school for three months, to encourage the pupils and to participate in the capital’s deaf community.

Rural deaf communities are harder to spot; eastern Fife may have had one, as, in the NSA, twenty ‘deaf and dumb’ people (including members of three deaf families) were recorded in five different parishes within 15 miles of each other. One Fife parish, Kilconquhar, is the only example where both the OSA and the NSA mention deaf parishioners; in the OSA, they are described as ‘abundantly sensible and active, and attend public worship regularly.’ Another rural example comes from the west coast, where the NSA for Portpatrick gives an insight into the lives of two ‘blind, deaf and dumb’ (or deaf-blind) siblings, living in a parish that included four other ‘deaf and dumb’ people. The 73-year-old sister and 66-year-old brother were both born deaf, but had been become blind in their 40s – possibly due to the genetic condition we now call Usher Syndrome. Deaf-blind people often use a tactile form of their sign language called ‘hands-on’, which is what Portpatrick’s minister may have meant when he wrote that the siblings ‘can be made to understand by means of touch what their friends find it necessary to communicate to them for their bodily comfort and personal safety.’ Their lives are described in a few short lines:

He can attend to the fire to supply it with fuel when it is required. She is remarkably particular as to her dress. Both can be made to understand when any one is present with whom they have formerly been acquainted; and when they are informed that the minister is present, they compose themselves, and assume a grave and serious aspect.

Outside official school and institutional records, it can be difficult to find details relating to the lives of ordinary deaf people, yet, as the Statistical Accounts of Scotland show, the details can be there beneath the surface, tantalising and incomplete. Human diversity has been a constant throughout history, and the lens through which we view history is forever widening beyond the traditional fixation with ‘the great and good’ to include the social history of working people, of women, of ethnic and other minorities – in short, to include the voices that may not have been heard or, in the case of deaf history, seen. There have been deaf people negotiating living in a hearing world throughout history and, although the record is vague, deaf lives can often be found hidden in the pages of ‘hearing’ documents. Through these, deaf history can be brought into existence.

Ella Leith

We hope you have enjoyed this post: it is characteristic of the rich historical material available within the ‘Related Resources’ section of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland service. Featuring essays, maps, illustrations, correspondence, biographies of compliers, and information about Sir John Sinclair’s other works, the service provides extensive historical and bibliographical detail to supplement our full-text searchable collection of the ‘Old’ and ‘New’ Statistical Accounts.

[1] Although we have no record of the signs they used, we know that deaf people were signing together in Ancient Greece, in the Scottish royal court in the 15th century, and in England and France in the 16th century. Today, British Sign Language (BSL) is used across the British Isles; however, throughout this blog I use the terms ‘sign language’ and ‘signing’ rather than referring to BSL, because the signs used in the 18th and 19th centuries may have differed considerably from the language as it is today.

Sources

Anthony Boyce and Pam Bruce, Loyal and True: The Life and Times of Alexander Drysdale (1812-1880) (Winsford: Deafprint, 2011)

Rev. Peter Chalmers, Historical and Statistical Account of Dunfermline (London: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1844-1859)

John Hay, Deaf Edinburgh: The Heritage Trail (Warrington: British Deaf History Society 2015)

Peter Jackson, Britain’s Deaf Heritage (Edinburgh: Pentland Press, 1990)

John Vickery Van Cleve, Deaf History Unveiled: Interpretations from the New Scholarship (Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University press, 1993)

Old Statistical Account: parishes of Aberdalgie, Kilconquar

New Statistical Account: parishes of Dunfermline, Kilbarchan, Portpatrick

Bridging Gaps at the British Museum

The overwhelming setting of the British Museum played host to this year’s Museums Computer Group “Museums and the Web” Conference, and as usual, a big turnout from museums institutions all over the UK came, bursting with ideas and enthusiasm. The theme (“Bridging Gaps and Making Connections”) was intended to encourage thought about identifying creative spaces between physical museums collections and digital developments, where such spaces are perhaps too big, and how they can be exploited. As usual, there was far too much interesting content to cover fully in a blogpost- everything was thought-provoking, but I’ve picked out a few highlights.

The overwhelming setting of the British Museum played host to this year’s Museums Computer Group “Museums and the Web” Conference, and as usual, a big turnout from museums institutions all over the UK came, bursting with ideas and enthusiasm. The theme (“Bridging Gaps and Making Connections”) was intended to encourage thought about identifying creative spaces between physical museums collections and digital developments, where such spaces are perhaps too big, and how they can be exploited. As usual, there was far too much interesting content to cover fully in a blogpost- everything was thought-provoking, but I’ve picked out a few highlights.

Two projects highlighted collaboration between museums, which can be creatively explosive, and immediately improve engagement. Russell Dornan at The Wellcome Institute showed us #MuseumInstaSwap, where museums paired off and filled their social media feeds with the other museum’s content. Raphael Chanay at MuseoMix, meanwhile, arguably took this a step further by getting multiple institutions to bring their objects to a neutral location (Iron Bridge in Shropshire, Derby Silk Mill), and forming teams to build creative prototypes out of them across the digital and physical spaces. Could our museums collections be exploited in similar ways? Who could we partner up with?

I like to think that our “digital and physical” teams in L&UC collaborate very effectively. Keynote speaker John Coburn from TWAM (Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums) spoke of the importance of this intra-institution collaboration. You will (almost) never find a project that is run entirely from within the digital or physical sphere (Fiona Talbott from the HLF confirmed this- 510 of 512 recent bids had digital outputs relating to physical content), and the ability of the digital area and the content providers to communicate and work together is key. One very good example of this was the Tributaries app, built with sound artists, the history team, archives and so on, to put together an immersive audio experience of lost Tyneside voices from World War I. He also spoke of their TNT (Try New Things) initiative (also creatively explosive!) where staff sign up to do innovation with the collections, effectively in their spare time. With the Innovation Fund encouraging creativity, how do we work this into our daily lives? Can we? If not, how do we incentivise people to do it outwith their spare time? One of the gloomier observations of the day was that, with austerity, there is less and less money in the sector, which is likely to get worse after next month’s spending review. This austerity can breed creativity, though, and it’s good for digital, because people need to ‘work smarter’.

Another really interesting project is going on at the Tate, where they are combining their content with the Khan Academy learning platform. Rebecca Sinker and colleagues showed us how content can be levered and resurrected through a series of video tutorials around the content (be they archival, technical, biographical etc). Pushing the collaborative textual content from the comments area on the tutorials through to social media allows further engagement and new perspectives on the museum objects. Speaking personally, I have had little exposure to our VLE, but I’m quite sure that developing an interface between it and our collections sites could be highly beneficial.

That’s all the tip of the iceberg, though, so take a look at the programme link at the top to find out about lots of other interesting projects.

Outside of the lecture theatre, I had some really interesting conversations with people who have exactly the same problems as ourselves: building image management workflows, incorporating technological enhancements to content-driven websites, and thinking about beacon technology (the sponsors, Beacontent, deserver top marks for the name at least). Additionally, a tour of The Samsung Digital Discovery Centre– where state of the art technology meets British Museum content to improve the experience for children, teenagers, and families- was highly informative.

Scott Renton, Digital Developer

Keeping it in the family

At New College Library we often receive enquiries from individuals interested in researching their family bibles, who have identified that we hold the same or similar edition at New College Library. Inside these family bibles births, marriages and deaths may have been recorded, making each one a unique resource for family history research. Read More

Grand Tour Slide Show

Some time ago we digitised the hand coloured glass slides in the Cavaye collection, but we didn’t have time to do the much larger black and white part of the collection. So when our project photographer John Bryden, found a bit of spare time, we were delighted to have the remaining slides completed.

The whole collection is wonderful, apparently from a Grand Tour of Europe around the turn of the 20th century. I suspect that many of the slides were bought on the trip, much like we buy postcards today. Some of them were probably only lovingly hand tinted on return to Britain- in one of Palermo the tinting appears to be half finished. Read More

Trial access to BrowZine

The Library is running a trial of BrowZine until 18th January. BrowZine is a new application that allows you to browse, read and follow thousands of the library’s scholarly journals (see list of publishers at http://support.thirdiron.com/knowledgebase/articles/132654-what-publishers-do-you-support) either from your desktop/laptop or via an app for your Android and iOS mobile devices.

Articles found in BrowZine can easily be synced up with Zotero, Mendeley, Endnote, Evernote, Dropbox or other services to help keep all of your information together in one place.

To learn more, please take a look at this short “BrowZine on Campus” video below:

With BrowZine, you can:

– Browse and read journals: Browse journals by subject, easily review tables of contents, and download full articles

– Create your own bookshelf: Add journals to your personal bookshelf and be notified when new articles are published

– Save and export articles: Save articles for off-line reading or export to services such as DropBox, Mendeley, Endnote, Zotero, Papers and more

To learn more and start using BrowZine on your mobile device, visit http://thirdiron.com/download/. Getting started is easy! From your Android or iOS device, find BrowZine in the Apple App, Google Play or Amazon App store and download it for free. When initially launching BrowZine, select University of Edinburgh from the drop down list. Enter your EASE login. Start exploring BrowZine!

If you would like to access the Desktop/Laptop option on or off campus, please go to http://www.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/login?url=http://browzine.com/libraries/665/ and sign in with your EASE login (please note MyBookshelf and Reading List option is not available yet for the Desktop version).

For further info on Browzine, there is an FAQ/Help page at http://support.thirdiron.com/knowledgebase/topics/22734-help-for-browzine-users

For further info on Browzine, there is an FAQ/Help page at http://support.thirdiron.com/knowledgebase/topics/22734-help-for-browzine-users

Feedback and further info

We are interested to know what you think of BrowZine as an alternative way of accessing our e-journal A-Z list as your comments influence purchase decisions so please do fill out our feedback form.

A list of all trials currently available to University of Edinburgh staff and students can be found on our trials webpage.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....