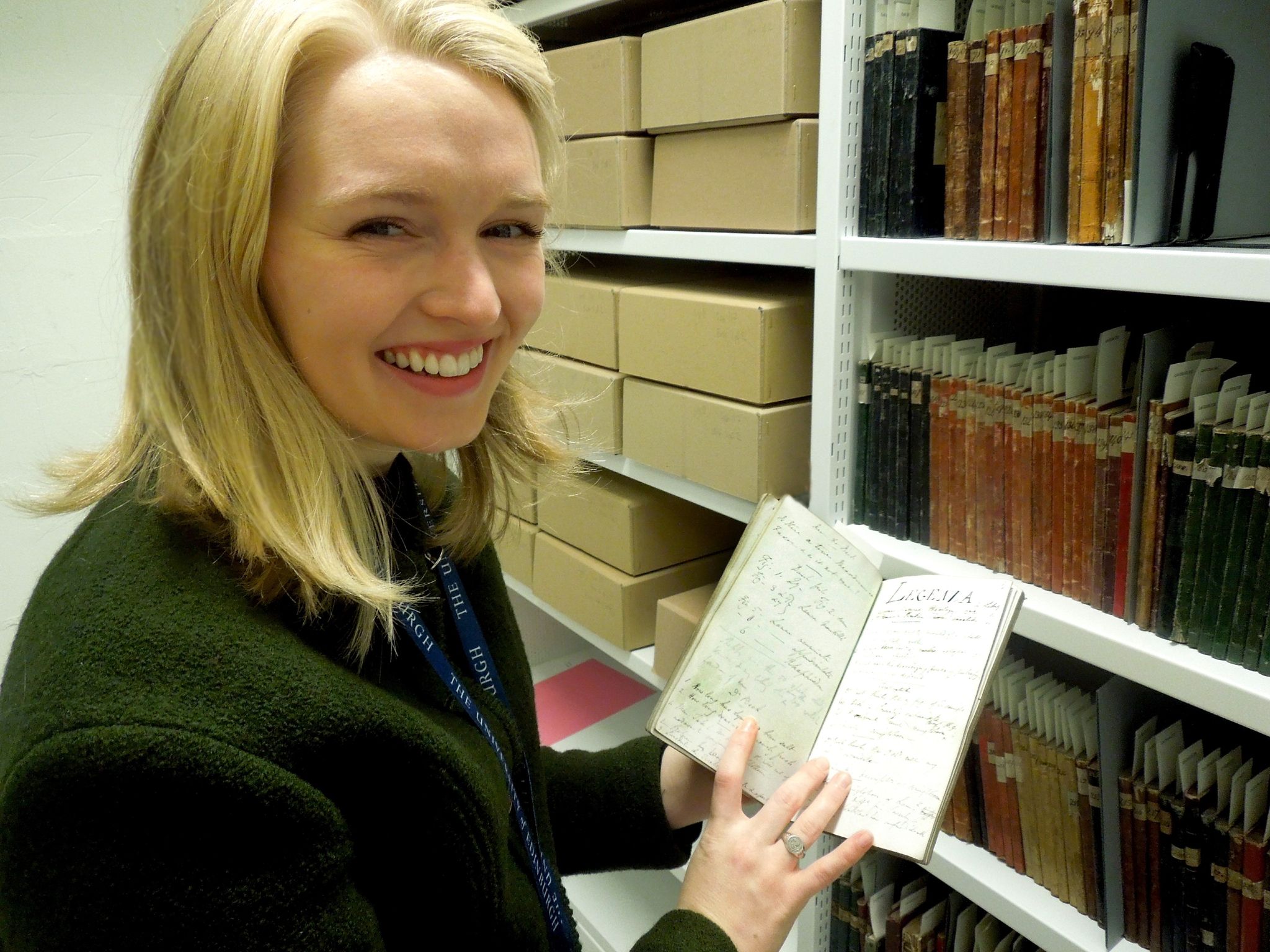

This week in the stores, I began to delve into the box lists which describe the new-to-us collection of further papers of Charles Lyell and the family which was received by the University in the summer through the Acceptance in Lieu scheme. These are 18 boxes of papers and correspondence of Lyell, and I have embarked on scanning these box lists which will prepare for more in-depth cataloguing in the short to medium term. Here is what most box lists look like:

Gideon Mantell was a frequent correspondent of Lyell, and their life-long relationship started with a bang in 1821, when Lyell casually called on Mantell while visiting his old school at Midhurst. Having heard tell of the doctor from some workmen in the nearby quarry, Lyell rode the 25 miles over the South Downs and knocked on Mantell’s door nearly at dusk. Presumably they might have known each other’s names from the Geological Society, but one would imagine the visit would still have come as surprise at best. However, common interest prevailed, a well-stocked fossil cabinet provided great amount of conversation, and the two reportedly gossiped until morning. (Bailey, p. 48) Their published letters cover all from scientific theories, discoveries, to the latest gossip and accounts from the GeolSoc and Royal Society, of which they were both members.

In a week which is dominated by a race for a vaccine, we see similar scientific rivalries in the early years of geological science. Today Mantell is known for bringing to light and describing dinosaur reptiles. These letters from 1851 with Lyell may relate to a legendary dispute between Mantell, Lyell, and Sir Richard Owen surrounding a reptile fossil which was found in ancient rock, which previously had only yielded fish. At this time, years before Darwin’s Origins of the Species, views of the evolution of life were split into two camps; progressionists (today, this sect is called orthogenesis) believed that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve to a particular goal, and most followers believed this to mean a trend of increasing biological complexity through time. Any description of a tree of life usually falls within this hypothesis. Lyell and Mantell opposed this belief, identifying as anti-progressionists. A famous dispute occured between Lyell, Mantell, and Owens when Mantell and Owens wrote opposing descriptions of this curious fossil. The legend resolved with Owens in the wrong, and Lyell and Mantell in the right, but research using the archival collections of Owens and Mantell proves the legend wrong, revealing that Lyell urged Mantell, thought infirm and ailing, to write the description long after Owens had already been tapped to view and describe the fossil, and it was Mantell and Lyell who were in the wrong. This is a woefully clipped version of events, but I find the true value of work with archives here: with access and research to correspondence archives such as this one, the true stories of history are told, and legends can be found faulty.

References:

Charles Lyell, Sir Edward Bailey, 1962

For more about this progressionist dispute, see Michael J. Benton’s Progressionism in the 1850s: Lyell, Owen, Mantell and the Elgin fossil reptile Leptopleuron (Telerpeton)

Elise Ramsay

Project Archivist (Sir Charles Lyell Collection)

![An image of a notebook page written in pencil or light pen in which Charles Lyell writes his thoughts on University education. Transcript: What is the portion of those who ought to have a Univ[ersit]y Ed[ucatio]n in England. Who really have one? 1. Learn number Att[ourn]ys & their cle-rks. Barristers not Oxf[or]d or any Univ[ersit]y men - Dissenter who an barrister, attournies, or spe-cial pleaders &c [etc] 2. Engineers, Architects, Surveyors 3. Physician dissenters how many Surgeon d[itt]o. Discipline was intended. ought not those below 16 to be required to go to church.](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/lyell/files/2020/09/0183475c.jpg)

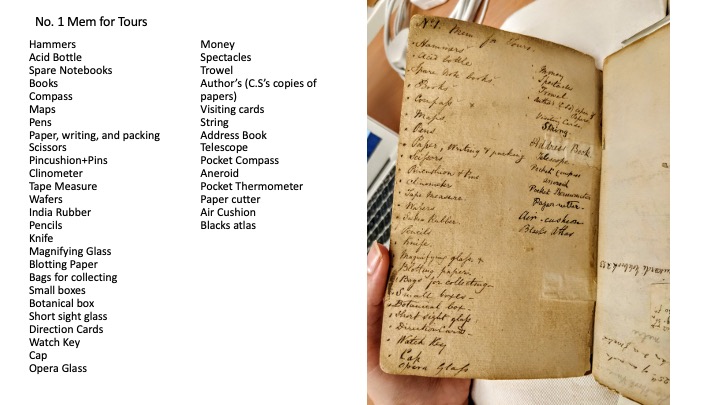

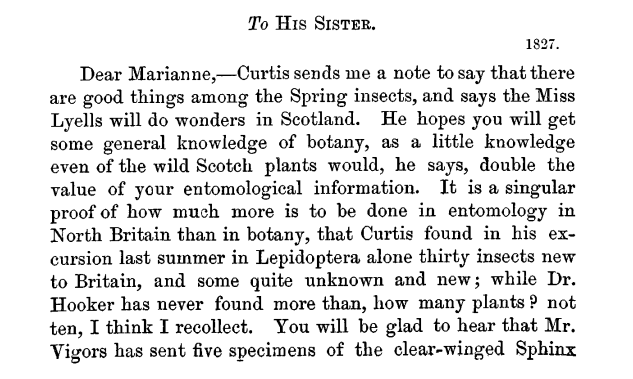

During this lockdown, the Lyell Project has been able to continue enhancing metadata, despite having no access to the Lyell notebooks, thanks to some quick digitisation done by the amazing team at the DIU prior to lockdown. We’ve been working quite a bit with Notebook No. 4, from 1827, when Lyell was balancing his two callings; the law and geology. In 1825 his eyesight was no longer ailing him as it had been years previously, and following his father’s wishes, he was called to the bar and joined the Western Circuit for two years. But during this time, as we can see from the Notebook, he also maintained fervent correspondence with fellow geologists, read the works of George Poulett Scrope, and Lamarck, and thereby fostered a great curiosity for the volcanic Auvergne region in France. In 1825 he joined Scrope as a Secretary to the Geological Society, and contributed frequently to the Quarterly Review (published by John Murray, the archive of issues

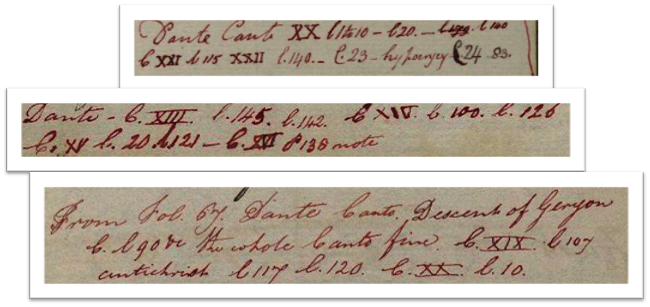

During this lockdown, the Lyell Project has been able to continue enhancing metadata, despite having no access to the Lyell notebooks, thanks to some quick digitisation done by the amazing team at the DIU prior to lockdown. We’ve been working quite a bit with Notebook No. 4, from 1827, when Lyell was balancing his two callings; the law and geology. In 1825 his eyesight was no longer ailing him as it had been years previously, and following his father’s wishes, he was called to the bar and joined the Western Circuit for two years. But during this time, as we can see from the Notebook, he also maintained fervent correspondence with fellow geologists, read the works of George Poulett Scrope, and Lamarck, and thereby fostered a great curiosity for the volcanic Auvergne region in France. In 1825 he joined Scrope as a Secretary to the Geological Society, and contributed frequently to the Quarterly Review (published by John Murray, the archive of issues  Another curious element in this notebook is the inclusion of citations to works by Dante, namely Dante’s Inferno. These appear often among entries on other subject, and without explanation. Clearly, this an excellent area of research, as we know Lyell’s father was a great scholar on Dante.

Another curious element in this notebook is the inclusion of citations to works by Dante, namely Dante’s Inferno. These appear often among entries on other subject, and without explanation. Clearly, this an excellent area of research, as we know Lyell’s father was a great scholar on Dante. Lockdown may seem frustrating and tiresome to some, but it has made space for a few spontaneous and unexpected collaborations!

Lockdown may seem frustrating and tiresome to some, but it has made space for a few spontaneous and unexpected collaborations!

The Friends of Edinburgh University Library played a vital role in helping to acquire the Charles Lyell notebooks. They celebrate that acquisition in the new issue of

The Friends of Edinburgh University Library played a vital role in helping to acquire the Charles Lyell notebooks. They celebrate that acquisition in the new issue of