Free exhibition in the Main Library Exhibition Gallery (ground floor),

Open from 27th October 2023 – 30th March 2024, Monday to Saturday, 10am to 6pm

Over the last few months, our efforts have been focussed on pulling together all the work to date associated with the Charles Lyell Project, into an exhibition. It has taken a small army of experts, staff, interns, and volunteers to get us to this stage – and we are nearly there. Here is a look behind the scenes…

Getting down to writing – what will be in effect – the first major exhibition on Sir Charles Lyell was a fairly daunting task. The science Lyell is writing about was new; today it can be recognised as ecology, climate and Earth studies, but in Lyell’s time it encompassed several different disciplines – geology, archaeology, geography, conchology, botany, zoology and palaeontology. The terminology is crucial, and, still under significant debate. Working in an era of imperial exploration and expansion Lyell’s travel through the slave plantations of the American South was controversial and remains disturbing. Despite his life’s work to gather, share and advocate for precise and authentic evidence in science, Lyell struggled to accept his friend Charles Darwin’s work on evolutionary theory. This exhibition explores these themes providing an unprecedented insight into how Lyell worked to establish a science that abridged deep divides of religion, race, culture, and politics.

Given these complexities, getting the right people on the exhibition team was vital, and it has been an absolute pleasure to work with Jim Secord, Director of the recently completed Darwin Correspondence Project. As Jim says, the reality is,

“getting into the 1830s is relatively easy, it’s the getting out that’s the problem”.

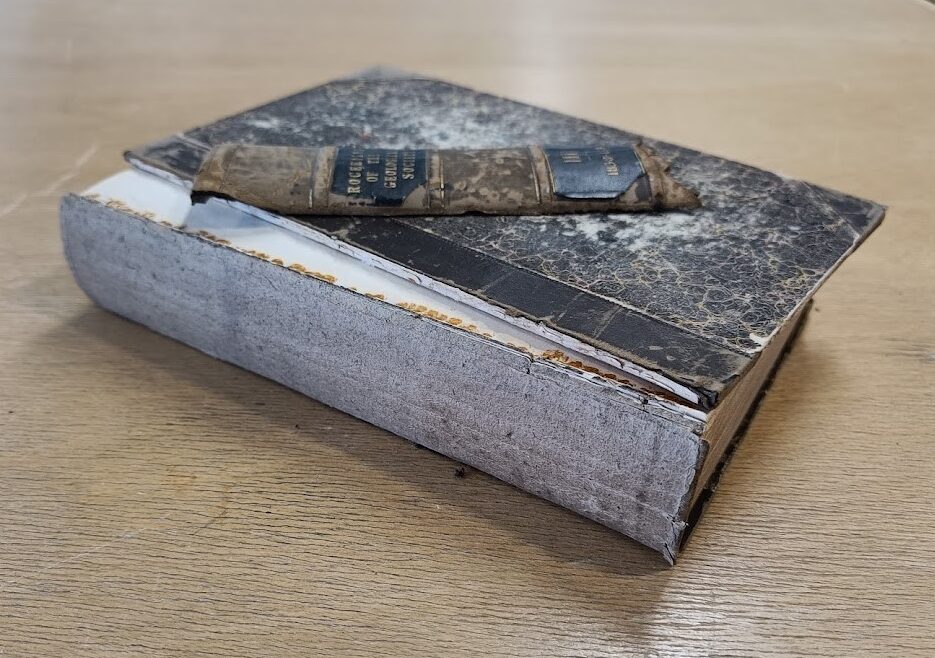

Jim has contributed a wealth of knowledge and experience , selecting rare books held by the University that add context to Lyell’s life and career, including motivators, Isaac Newton and James Hutton, and contemporaries such as Frederick Douglass. It has been fascinating to see how books held within the Library collections connect to Lyell’s work.

University Library books, that have been used by students over the years, contribute context to Lyell’s work.

Robyn studies her successful trial to create a bespoke stand for the notebooks; re-useable and recyclable.

Jim and Will during ‘object selection’ day, working on choosing what items to feature.

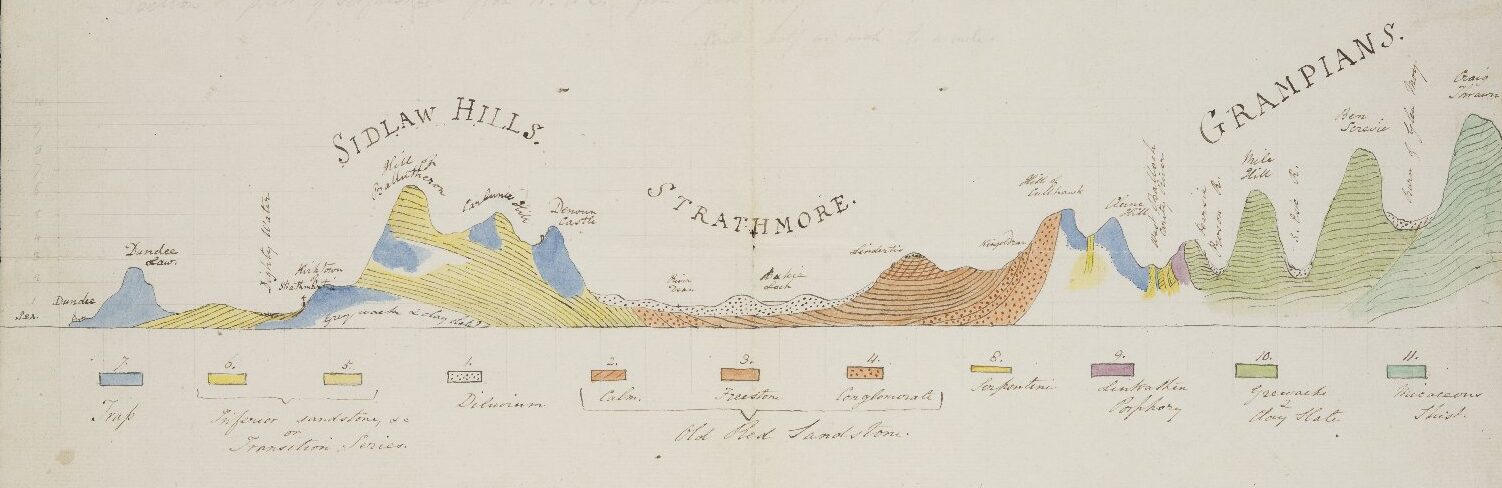

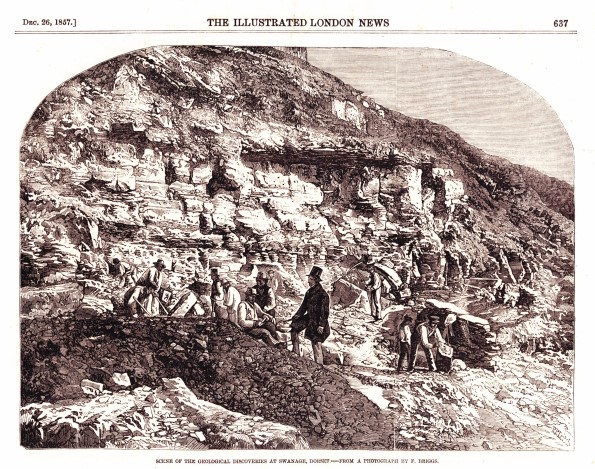

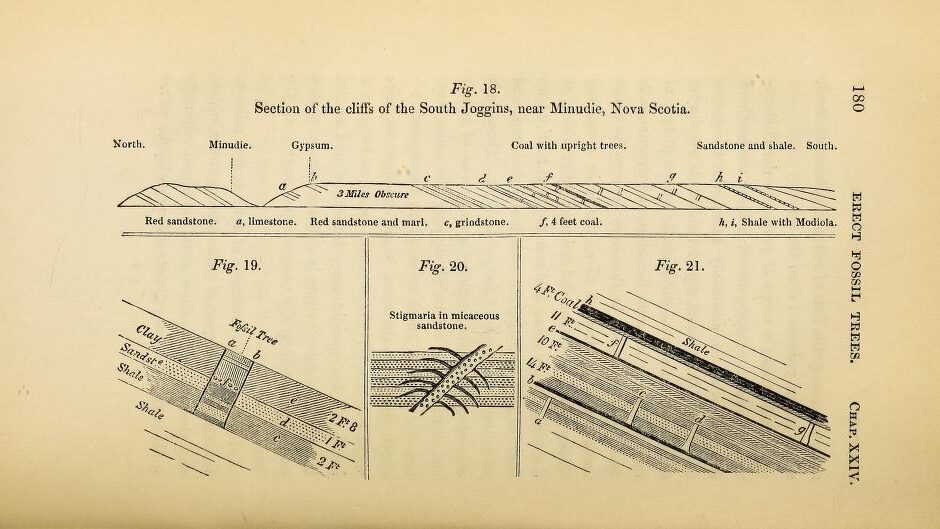

Having completed his dissertation on Lyell’s contribution to prehistoric archaeological study, Will Adams has also been our Lyell Research Intern, tasked with curating a series of case studies, demonstrating how Lyell researched and gathered evidence to support his theories. Five display cases later, look out for Lyell as a ‘Principle Investigator’ (play on words intentional!) as he searches for evidence to support his theories on Volcanoes, Niagara, and Sea Serpents.

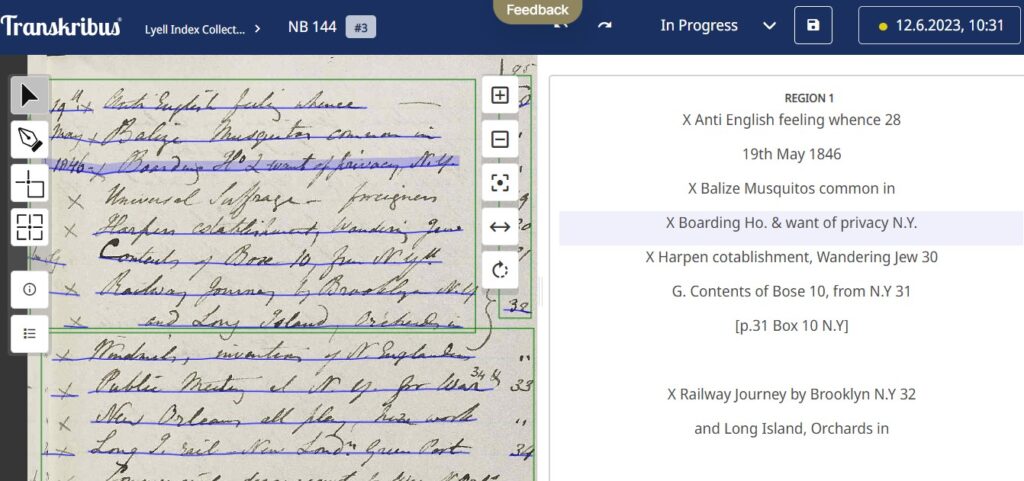

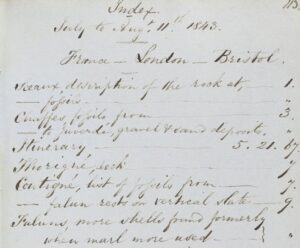

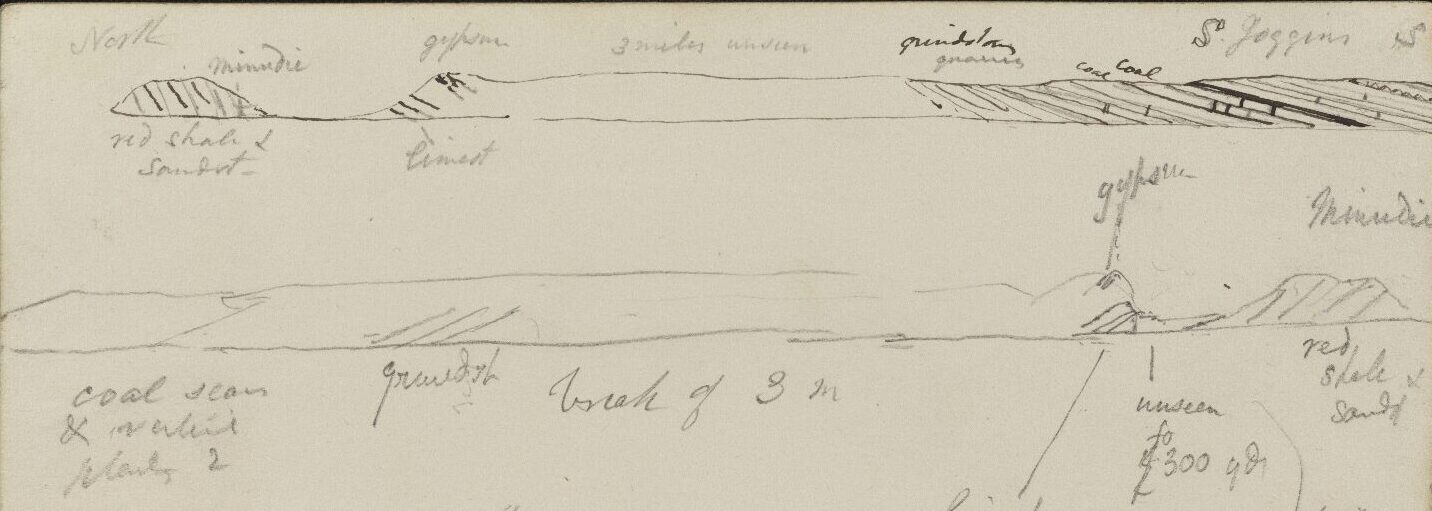

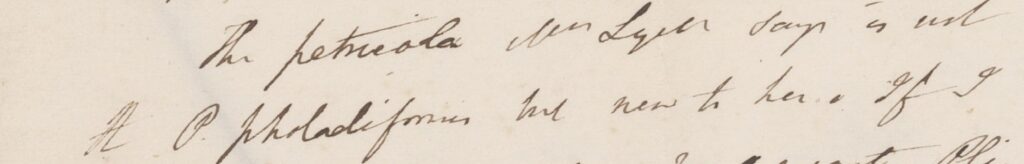

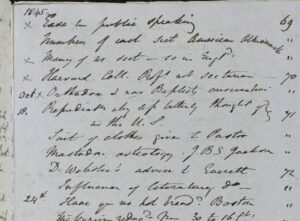

Will’s work has been supported by that of Lyell Summer Intern, Harriet Mack, and a crew of remote volunteers – Drew, Beverly, Bob and Ella – are are currently working to away using the digital images to transcribe notebook indexes. In the course of trying to understand them, we’ve googled, mapped, fact checked, and reached out to local people, familiar with where Lyell was working.

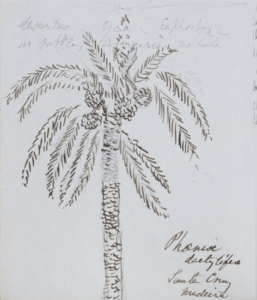

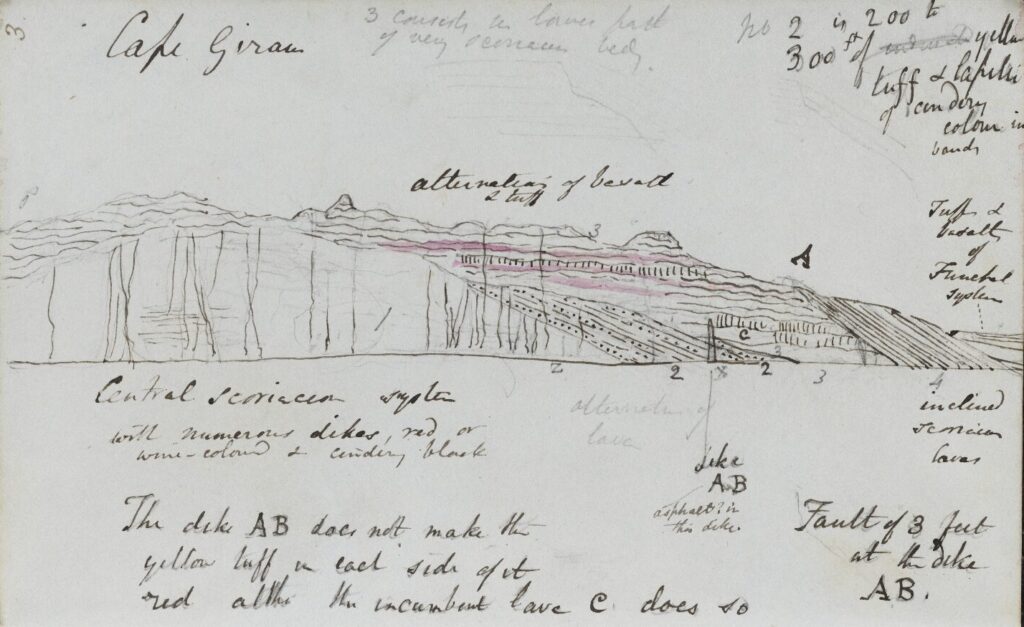

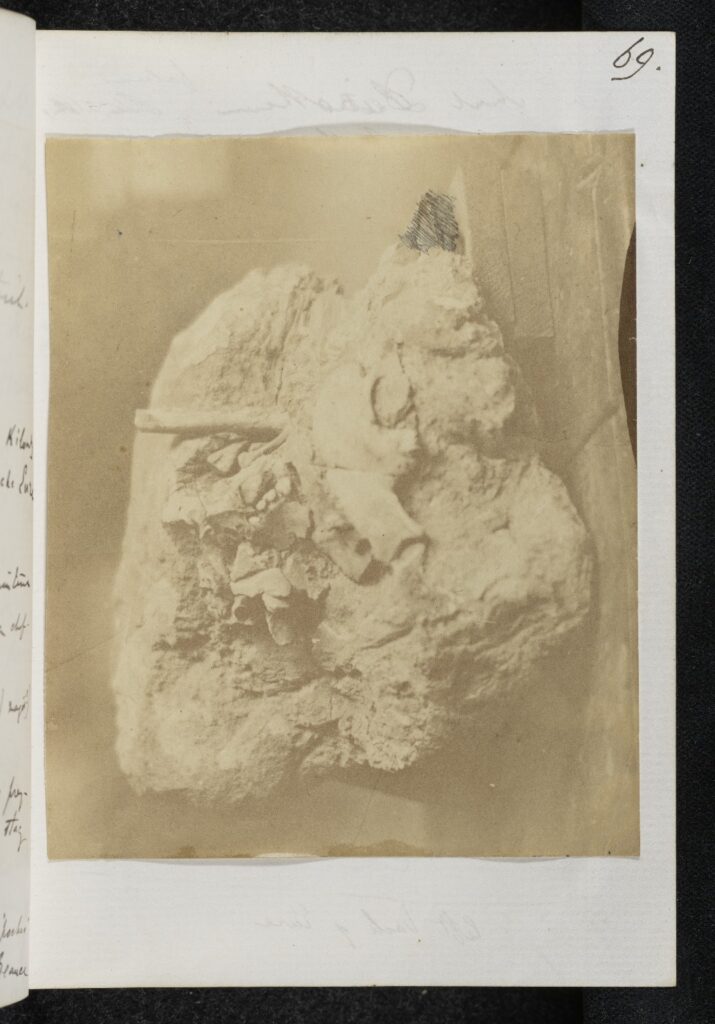

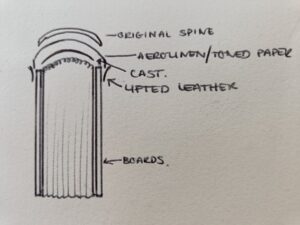

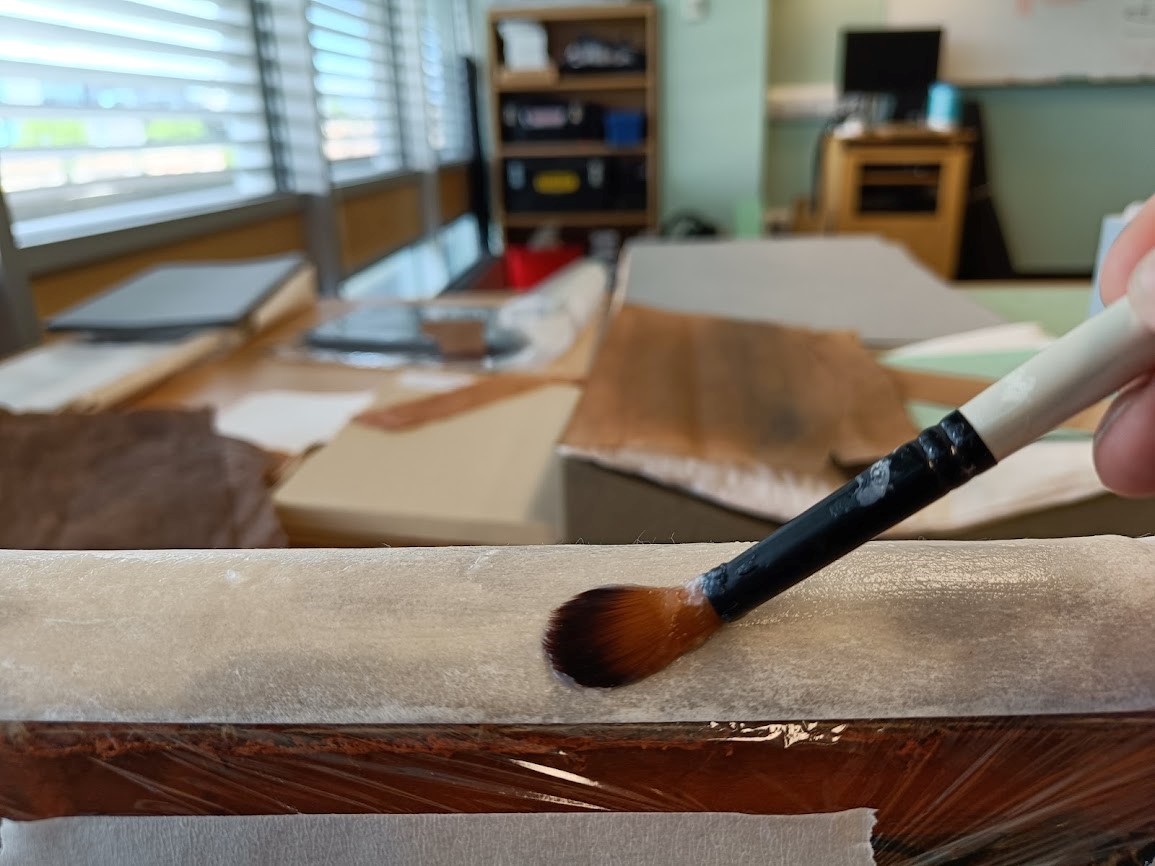

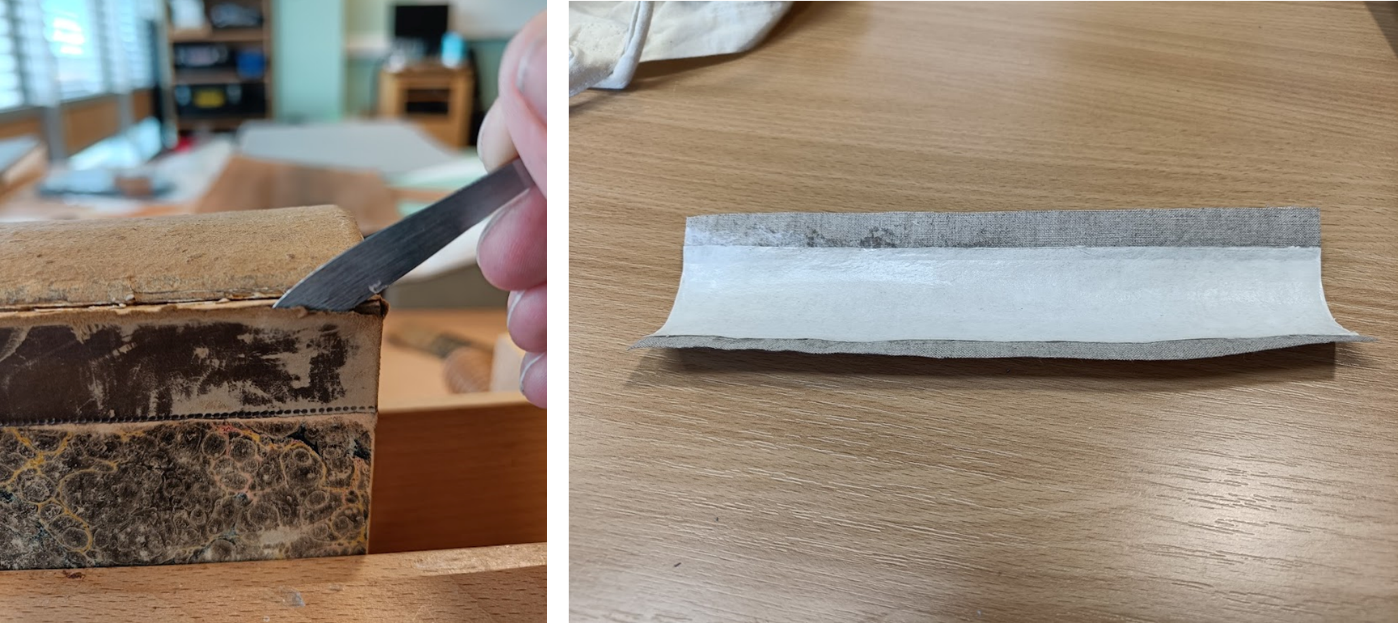

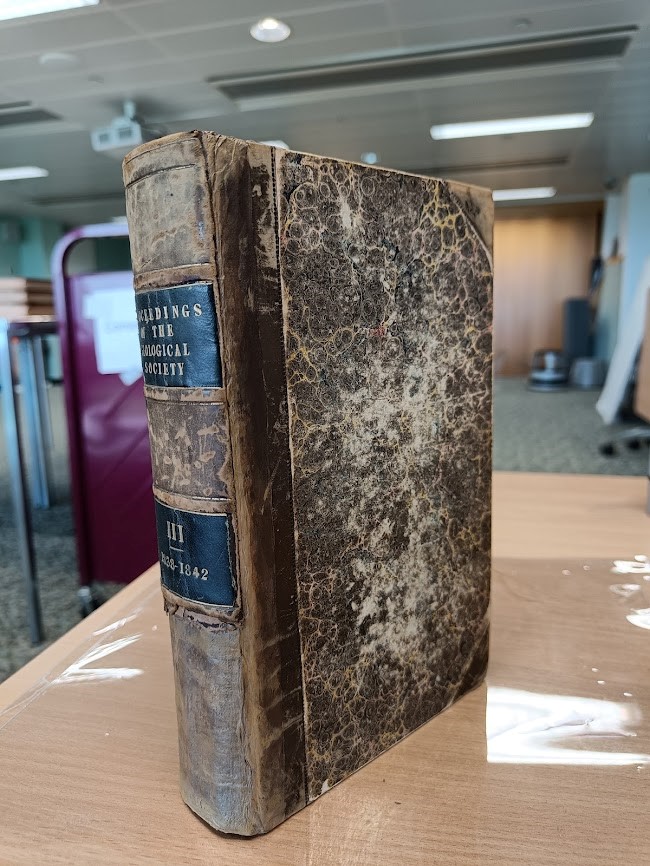

Notebooks are used in the exhibition to show how Lyell worked to gather evidence to support his theories.

The volunteer’s work has really opened up that section of the archive, producing rich descriptions that have highlighted previously unseen sections in the notebooks that will feature in the exhibition. We have worked to include their reflection on this experience, enabling us to shine a contemporary light onto the notebooks, and all the different hands that appear within their pages.

Team ‘Lyell Finds’ -Will, Dr. Gillian McCay, & Hattie at the Cockburn Geological Museum.

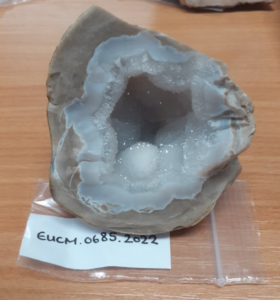

Lyell’s specimens were a key tool for him, and Dr. Gillian McCay of the Cockburn Geological Museum has been an integral part of our progress to understand how they connect to the archive. From the outset, everyone has been on the lookout for references to collection items (fed into and logged in a very lively teams chat ‘Lyell Finds’) and Will, through his dissertation, has been able to re-establish the events that link notebooks and specimens to Lyell’s work on the antiquity of man. There is much more work to be done in this area – and we hope the exhibition will encourage this.

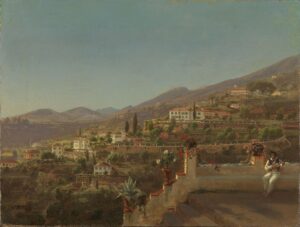

Today Lyell’s questions are still relevant, and the ways in which he worked (not always successfully) to answer them can add to our own understanding. Travelling relentlessly, and often accompanied by his wife, Mary, Lyell spent his life putting time to work, chasing volcanoes, visiting coastal, industrial and heritage sites, exploring strata, caves, waterfalls, quarries, and mines. The resultant rich data contained in his archive transports us through time.

In working together on the project to open up Charles Lyell’s comprehensive archive, and in preparing this exhibition, we find we have walked in his footsteps – creating a network of experts and local people, and using different tools to consolidate our understanding.

Pamela McIntyre, Strategic Projects Archivist, Heritage Collections, University of Edinburgh