This month we hear from Lyell Project Archivist Elise Ramsay and Project Volunteer Erin McRae. Elise and Erin each reflect on their recent progress transcribing the Sir Charles Lyell notebooks using ground-breaking AI and machine learning, and their work together to develop this incredible AI tool for further use with the Lyell collections.

Elise Ramsay

Lyell Project Archivist

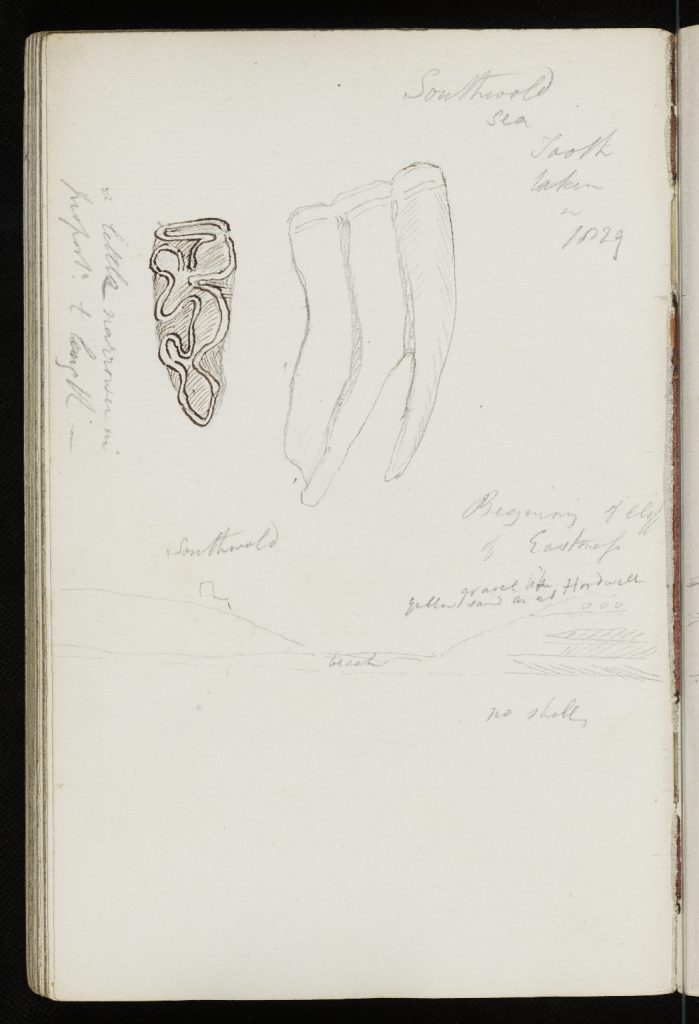

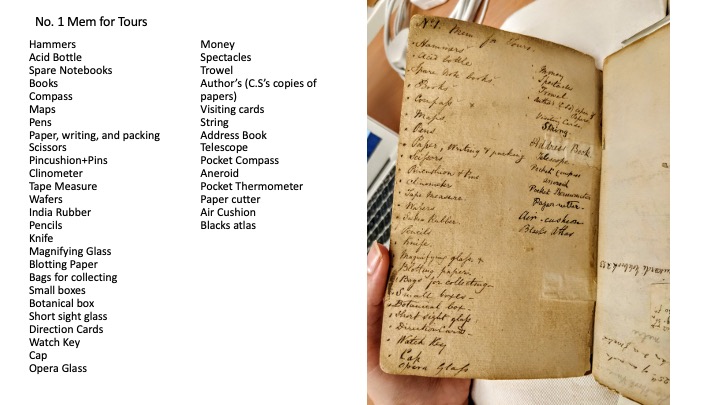

For me, the written word is the most captivating and characterful element of the Sir Charles Lyell collections. When reading Lyell’s own words on the page in graphite and ink, I can tell when he is writing from a desk, or in the field. In decoding his idiosyncrasies, I have come to understand a bit of the man himself. Understanding Lyell’s handwriting is the key to opening up this internationally significant collection. But it is also the first barrier. Lyell’s handwriting is of his time; often liberally abbreviated, topic specific, and faded. Complete transcription of the collection is paramount to accessibility, and recently, we have made some exciting progress towards this goal.

In early March 2021, the Charles Lyell Project team took part in hosting the EDITOR Transcription virtual workshop. In preparation for the workshop, two digitised notebooks from the Lyell collections (MSVII and Notebook No 4) were selected to be trialled with the Transkribus platform. Over 8 weeks, EDITOR project interns Evie Salter and Nicky Monroe transcribed these notebooks word for word. With this data, an algorithmic model of Lyell’s handwriting was created, effectively teaching Transkribus to recognise Lyell’s words on the page, and to decipher them automatically. This innovative work by the EDITOR Team, has revolutionised our systems and methods of cataloguing. Already we can see this balance of machine learning and human input has introduced new efficiency (and enjoyment!) to the task of transcription.

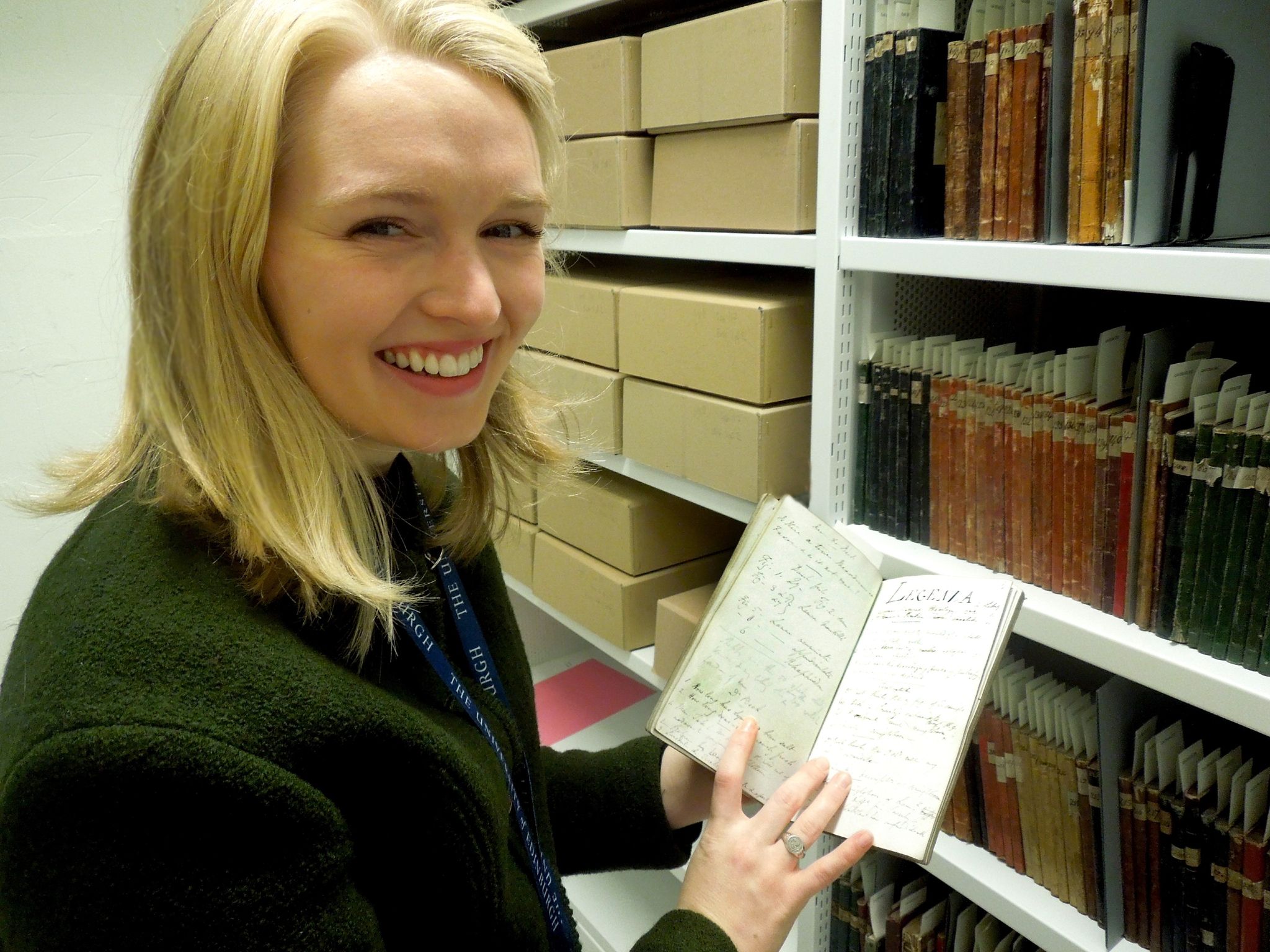

To build on this momentum, we were delighted to offer a remote volunteer opportunity aimed at trialling the newly created Transkribus model and testing the many features Transkribus offers. In this capacity, Erin McRae joined us in March, contributing to key cataloguing efforts and scoping the features of Transkribus for further use with the collections. Erin is a recent graduate from the MSc in History programme at the University of Edinburgh and holds an MA in Archives and Records Management from University College Dublin in Ireland. In only two months, Erin has produced tremendous material, and we are indebted to her. Here, Erin reflects on her first impressions of the Sir Charles Lyell collections and using Transkribus:

Erin MacRae

Lyell Project Volunteer

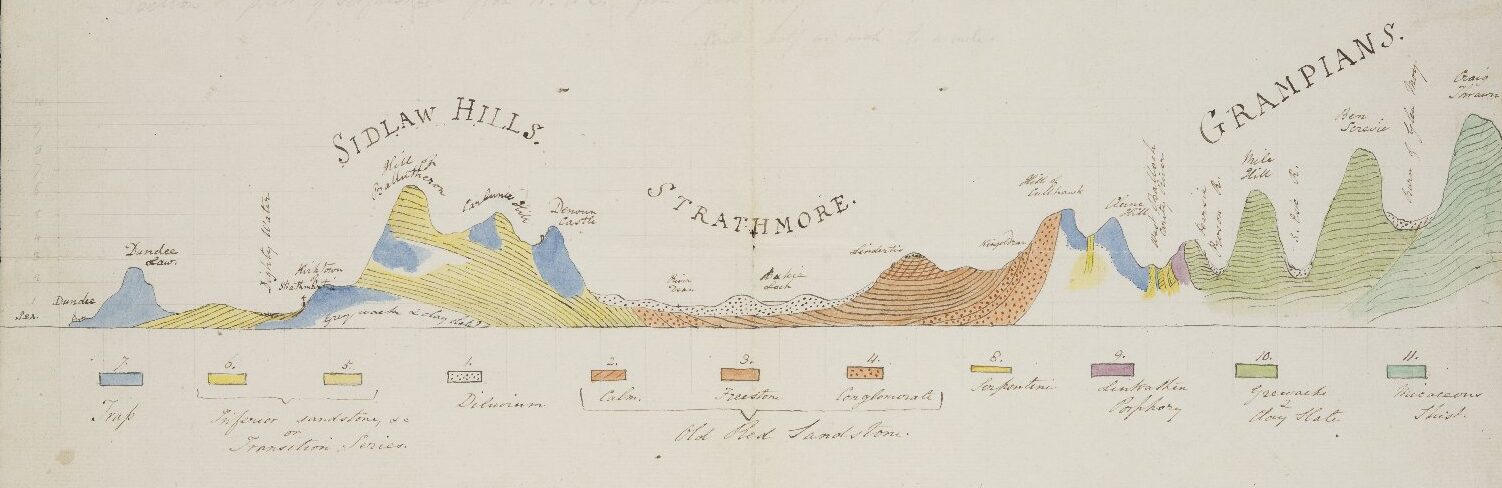

When I think of Sir Charles Lyell, I see a man in constant motion and possessing a thirst for knowledge that knew no boundaries. I can picture him observing the volatile Mount Etna, or immersed in the identification of mollusc species, or exploring geologic formations and petrified fossils millions of years old. I imagine him pausing to scribble down his observations in notebooks in his own inimitable style (a combination of English, French, Italian and Latin), so he wouldn’t miss any detail.

The detail of the collection is of untold value to researchers and presents interesting challenges as we describe the collection. In addressing these challenges, the Transkribus platform is an invaluable tool.

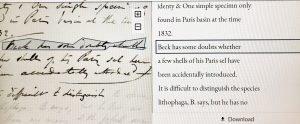

Transkribus is “a comprehensive platform for the digitisation, AI-powered text recognition, transcription and searching of historical documents – from any place, any time, and in any language.”1 Using the algorithmic handwriting model developed on the EDITOR project, we were able to upload more raw material from the Lyell collections to the Transkribus platform. In my recent work with Sir Charles Lyell’s notebooks, I found that Transkribus was able to decipher Latin species names with which I was unfamiliar. This saved me a significant amount of time and gave me the ability to transcribe much faster. An example of this occurred when Transkribus identified “Fissurella graeca”.2 A species of mollusc, this name has since been replaced by the accepted name “Diodora graeca”3 . It is remarkable that it was correctly interpreted by the software in the first place.

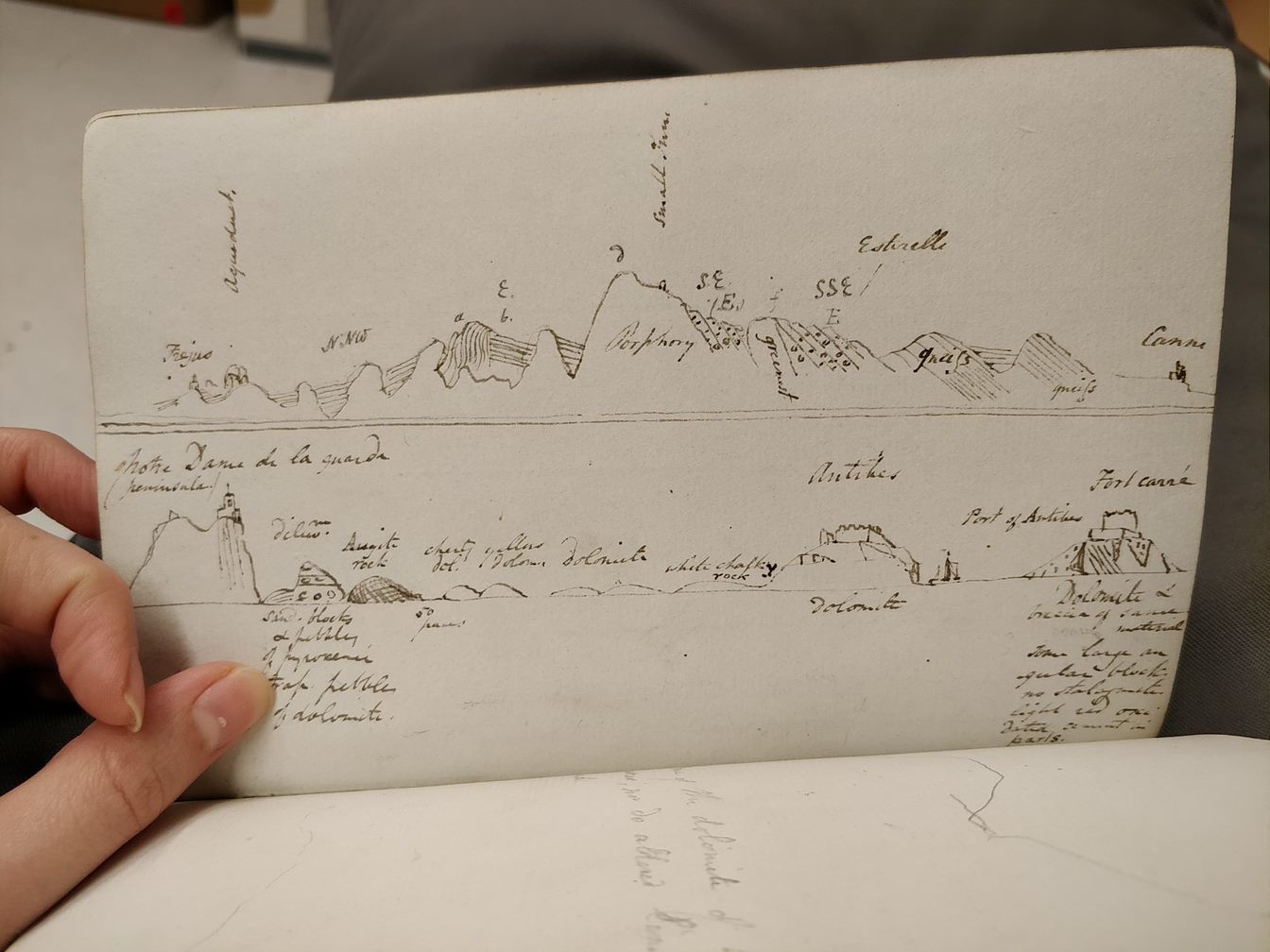

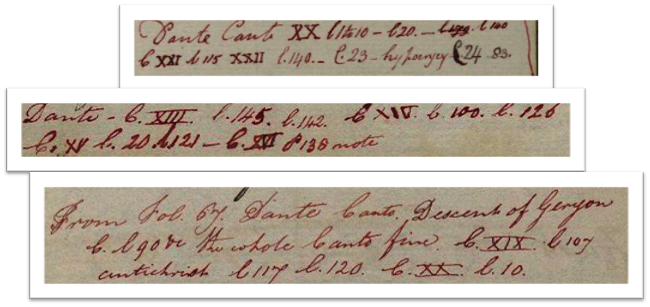

An example of transcription output from the Transkribus platform.

From Sir Charles Lyell Notebook, No. 65

(Ref: Coll-203/A1/65) – (with apologies for the poor quality image).

The transcriptions that Transkribus produces require minor to moderate spellcheck amendments, primarily where vowels are mistaken. There were some instances of errors in phrases, names, and once a whole line of text. In this case I transcribed this line myself which I had done previously with indexes in two other notebooks. These issues are minor and they do not detract from the immense amount of time I saved using Transkribus compared to transcribing without the aid of the algorithmic model. In particular, we were all struck by the accuracy of the model in recognising and deciphering antiquated species names. This was invaluable and changes the role of the transcriber.

The overall benefit of the Transkribus software is that it is helping us to develop a much more comprehensive approach to describing and interpreting the Sir Charles Lyell Collections. To a much greater degree than previously possible, we can document and unlock the life and travels of this principal figure in the evolution of the discipline of geology.

Elise Ramsay, Lyell Project Archivist

Erin McRae, Lyell Project Volunteer

Sources and further information:

1.“Transkribus.” Read Coop. Accessed April 19, 2021.

2. “Fissurella graeca (Linnaeus, 1758).” WORMS: World Register of Marine Species. Accessed April 19, 2021.

3. Ibid.

You can learn more about our revelatory transcription work on the Sir Charles Lyell Collections, part of the EDITOR project, on YouTube:

Editor Transcription Workshop: Day 1/Session 3 – Video 3 of 10 – YouTube

Editor Transcription Workshop: Day 2 /Session 3 – Video 6 of 10 – YouTube

We are excited to offer a new opportunity to experience this collection, a Zoom presentation by the Lyell Project staff on 10 December 2020 at 1pm GMT. This event reveals the ongoing work at the University of Edinburgh with the geological collection of Sir Charles Lyell, a rich corpus of material including his notebooks, family papers, and geological specimens.

We are excited to offer a new opportunity to experience this collection, a Zoom presentation by the Lyell Project staff on 10 December 2020 at 1pm GMT. This event reveals the ongoing work at the University of Edinburgh with the geological collection of Sir Charles Lyell, a rich corpus of material including his notebooks, family papers, and geological specimens.

![An image of a notebook page written in pencil or light pen in which Charles Lyell writes his thoughts on University education. Transcript: What is the portion of those who ought to have a Univ[ersit]y Ed[ucatio]n in England. Who really have one? 1. Learn number Att[ourn]ys & their cle-rks. Barristers not Oxf[or]d or any Univ[ersit]y men - Dissenter who an barrister, attournies, or spe-cial pleaders &c [etc] 2. Engineers, Architects, Surveyors 3. Physician dissenters how many Surgeon d[itt]o. Discipline was intended. ought not those below 16 to be required to go to church.](http://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/lyell/files/2020/09/0183475c.jpg)

During this lockdown, the Lyell Project has been able to continue enhancing metadata, despite having no access to the Lyell notebooks, thanks to some quick digitisation done by the amazing team at the DIU prior to lockdown. We’ve been working quite a bit with Notebook No. 4, from 1827, when Lyell was balancing his two callings; the law and geology. In 1825 his eyesight was no longer ailing him as it had been years previously, and following his father’s wishes, he was called to the bar and joined the Western Circuit for two years. But during this time, as we can see from the Notebook, he also maintained fervent correspondence with fellow geologists, read the works of George Poulett Scrope, and Lamarck, and thereby fostered a great curiosity for the volcanic Auvergne region in France. In 1825 he joined Scrope as a Secretary to the Geological Society, and contributed frequently to the Quarterly Review (published by John Murray, the archive of issues

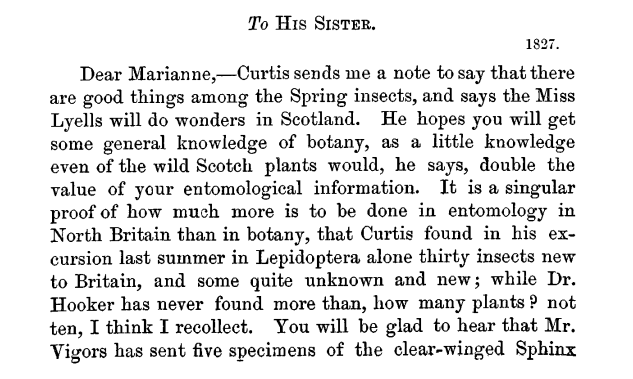

During this lockdown, the Lyell Project has been able to continue enhancing metadata, despite having no access to the Lyell notebooks, thanks to some quick digitisation done by the amazing team at the DIU prior to lockdown. We’ve been working quite a bit with Notebook No. 4, from 1827, when Lyell was balancing his two callings; the law and geology. In 1825 his eyesight was no longer ailing him as it had been years previously, and following his father’s wishes, he was called to the bar and joined the Western Circuit for two years. But during this time, as we can see from the Notebook, he also maintained fervent correspondence with fellow geologists, read the works of George Poulett Scrope, and Lamarck, and thereby fostered a great curiosity for the volcanic Auvergne region in France. In 1825 he joined Scrope as a Secretary to the Geological Society, and contributed frequently to the Quarterly Review (published by John Murray, the archive of issues  Another curious element in this notebook is the inclusion of citations to works by Dante, namely Dante’s Inferno. These appear often among entries on other subject, and without explanation. Clearly, this an excellent area of research, as we know Lyell’s father was a great scholar on Dante.

Another curious element in this notebook is the inclusion of citations to works by Dante, namely Dante’s Inferno. These appear often among entries on other subject, and without explanation. Clearly, this an excellent area of research, as we know Lyell’s father was a great scholar on Dante.