We are grateful to present another guest blog! This time from Timothé Lhoste who is currently completing his master’s degree studying History of Science at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in Paris. Timothé was in touch with the Centre for Research Collections requiring access to Charles Lyell’s Notebooks, and a very interesting story emerged, which sheds light on how Lyell worked. Read on to find out more about Timothé (and Lyell’s!) research …

I am working on a scientific controversy concerning a “human fossil” known as ‘L’Homme de la Denise’, and named to acknowledge its discovery in 1844 on the slopes of the Denise Mountain, near the city of Le Puy-en-Velay in the French Massif Central. The find was crucial, as from the outset, doubts hovered over the authenticity and the exact age of the discoveries. In fact, these bones and the gangue (the material that surrounds them) continued to fuel a lively discussion for more than a century.

Drawing on the method of the biography of scientific objects, such as Marianne Sommer’s Bones and Ochre: The Curious Afterlife of the Red Lady of Paviland, my study seeks to trace the impact of this object on the social world and vice versa. I am also interested in the evolution of different scientific interpretations of these objects.

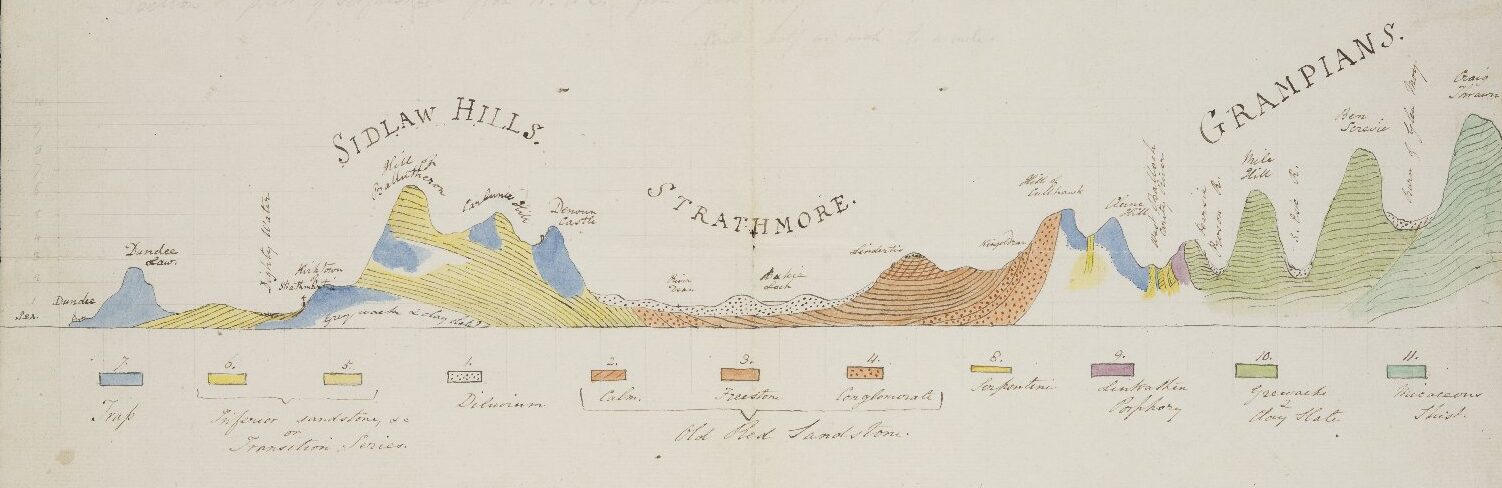

Charles Lyell’s Notebooks 239 and 240 document his trip to France during the summer of 1859, when he stayed in the vicinity of Le Puy-en-Velay from August 6th to 16th. He already knew this region, since he had visited it in 1828, as evidenced earlier in the run of his Scientific Notebooks in Notebook 12, dated 30 June – 21 July 1828. This area of the French Massif Central called Velay was of particular interest to Lyell. Volcanic formations had allowed the genesis and preservation of many fossil sites – and so of course would be of interest to Lyell the ‘volcano hunter’! – but in 1859, Lyell was now looking in particular for solid geological evidence of the antiquity of man.

For this reason, in the wake of Edmond Hébert and Edouard Lartet, he carried out investigations on the Denise site. He described the geology of the surroundings of Le Puy and carefully examined the human bones, which had been found in the region fifteen years before. During his stay, he met with local scholars such as Auguste Aymard, Bertrand de Doue, Pichot-Dumazel and Félix Robert. He even met Georges Poulett Scrope who came to complete his observations of the volcanoes of this region.

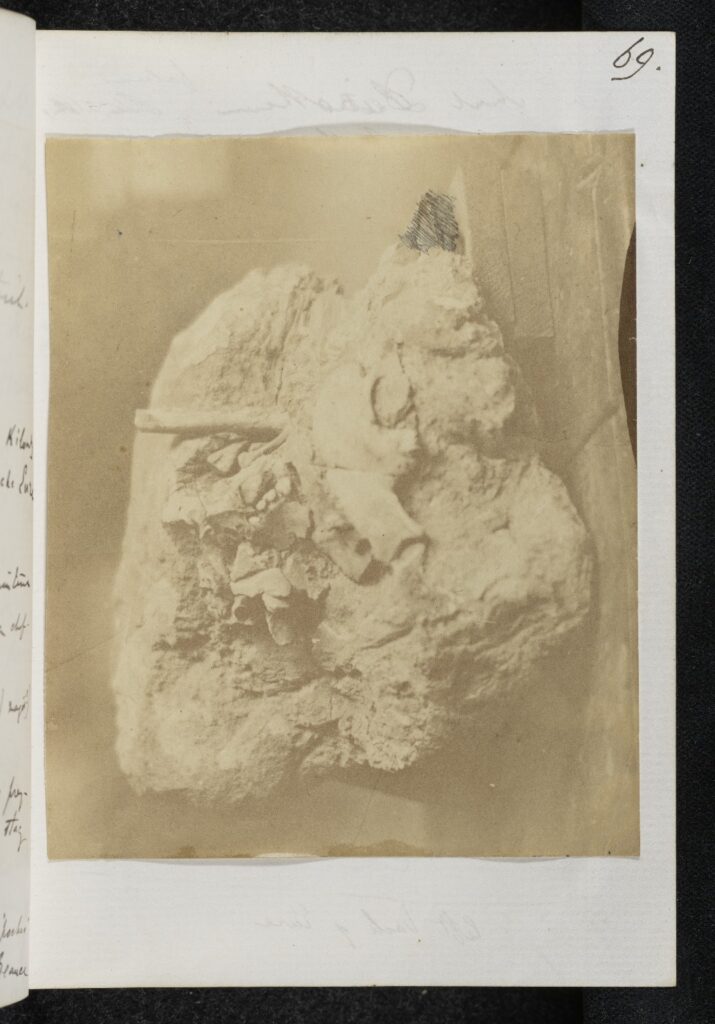

Lyell’s Notebooks testify to the richness of his observations. He visited other geological and paleontological sites (including Polignac, Cussac, Espaly, Saint Privat d’Allier, Doue, and La Roche Rouge), drew multiple sketches and talked with many local people. The most compelling piece of ‘evidence’ is a photograph of the “museum block” (bought in 1844 by Auguste Aymard and Bertrand de Doue for the local museum) which is glued into Lyell’s Notebook 240; this illustrates the particular interest that Lyell had in these bones.

Photograph acquired by Lyell showing the Denise block containing human bones which is glued into Notebook 240 page 69

Moreover, he also took Notebook 240 with him to Aberdeen for the 29th meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, along with the famous photograph commissioned by Prestwich and Evans, and featuring the local workmen, showing the position of a stone axe into the sedimentary series of Abbeville (and for more information on that, please see Clive Gamble’s article featured in the Geological Society of London’s Blog Photographs of the Drift ).

In his speech at Aberdeen (and later in his book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man published 1863), Lyell referred to the Denise findings, acknowledging their authenticity and he praised and acknowledged the scientific validity of the discoveries Jacques Boucher de Perthes had made in Abbeville.

However, Lyell could not commit to the idea of ‘L’Homme de la Denise’ as a proof of the contemporaneity of the man, and the latest eruptions of the Massif Central, refusing to give them any value of antiquity.

Thank you Timothé for sharing your research – we wish you all the best for the completion of your Masters degree. Thanks also to Caroline Lam, Archivist & Records Manager at The Geological Society. This enquiry initially drew our attention to the fact that there was an original photograph in the collection – in fact – one of only two glued into the Notebooks. We can now appreciate how important photography must have been to Lyell – and indeed to others working at that time. It has enabled us to ‘unearth’ many more related archives – we will revisit this topic!

Further Reading:

Lyell Charles, 1859, “On the occurrences of works of human art in post-pliocene deposits”, Twenty-Ninth meeting of the British association for the advancement of science, London, Murray.

Lyell Charles, 1863, Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, London, Murray.

Denise Man is of considerable importance from the point of view of human evolution. Wallace, Darwin’s associate, wrote briefly about the excavations in the Schmerlings Caves (Belgium) and at Denise (Le Puy, France), without actually naming these locations.

https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlps_fac_arw/6

Why was Denise Man of special interest to Wallace? He writes of the size of the skull of Denise Man being equivalent to that of contemporary humans (currently recorded as being roughly in the range, 1055-1500 ml). He went on to point out that fossilised remains of extinct mammoths were found in the same geological strata as Denise Man. Wallace’s puzzle was this: why did a hunter-gatherer need such a big brain, with the cognitive power of contemporary humans, when their existence was so simple at the time of these now extinct mammoths? To Wallace, the human ancestral brain at the time of Denise Man, had evolved beyond need and was therefore at odds with the theory of evolution which states more or less that evolution progresses according to need and not beyond need (with rare exception). It is slightly strange that Wallace, placing considerable emphasis on the importance of the size of the skull of Denise Man, did not record what the dimension of the skull actually was. In an attempt to explore this, I have discovered very little about Denise Man, let alone his skull size. I was unable even to discover what happened to these fossilised remains and whether they are currently located in a museum. If in a museum, it may yet be possible to measure or at least predict skull size from separated fragments. This business of the human brain having evolved to three times the size normally allowed by the body-size-brain-size relationship, has been described as the hardest task for the theory of evolution to explain. I am finalising a paper on the topic of this prima facie evolutionary glitch (“Wallace’s Riddle”) so if anybody can provide a Link to Denise Man’s skull dimensions, please feel free to email me:

coolwaverider@yahoo.co.uk

Editors Note:

In subsequent communication with Malcolm, he has indeed been able to confirm the present location of the fossilised remains of “DENISE MAN” at The Le Puy Museum https://www.musee.patrimoine.lepuyenvelay.fr/ .