A more personal take on our archives…

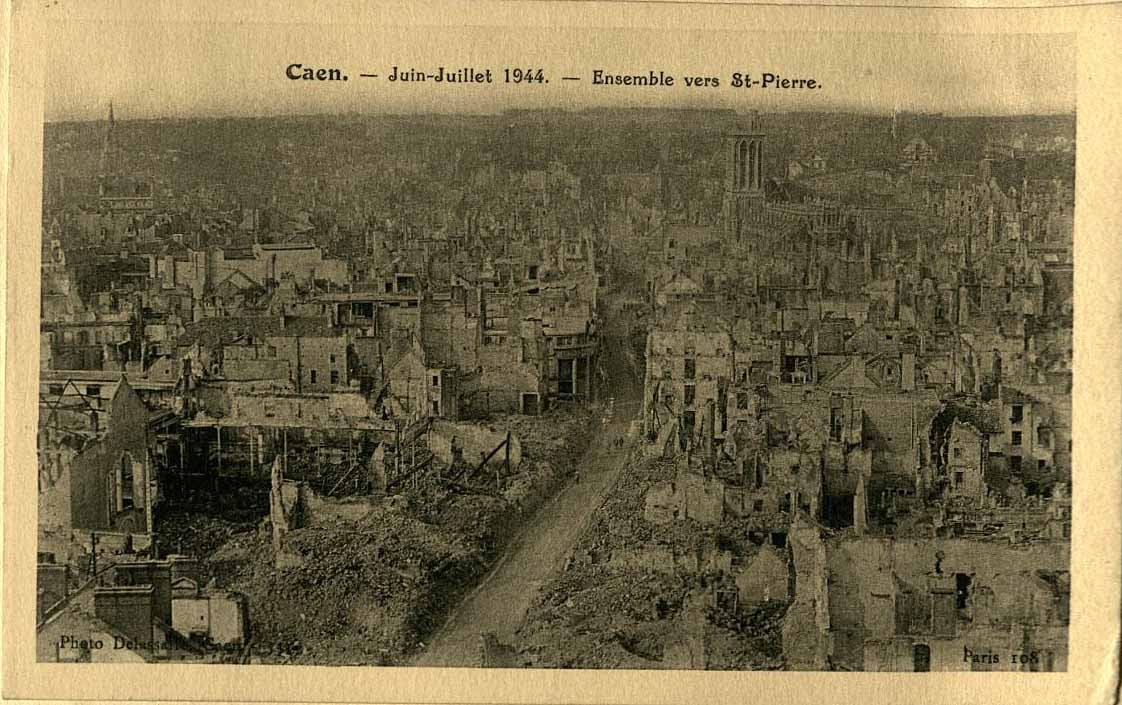

As any archivist knows, you can sometimes stumble upon archives with an unexpected and personal connection: this was the case for me when I found out that in the Special Collections of the Library was an album containing 175 photographs and postcards showing my home city, Caen, before and during the Second World War (Coll-164)… It immediately reminded me of my own grandparents, who had lived through the occupation, the bombing and finally the liberation of this medium-sized Norman city. They would always tell me stories about life during the war, and describe the way Caen looked before it: indeed, about 80 percent of the city was destroyed, in particular during the controversial bombing raid that preceded the ‘Operation Charnwood’ in July 1944.

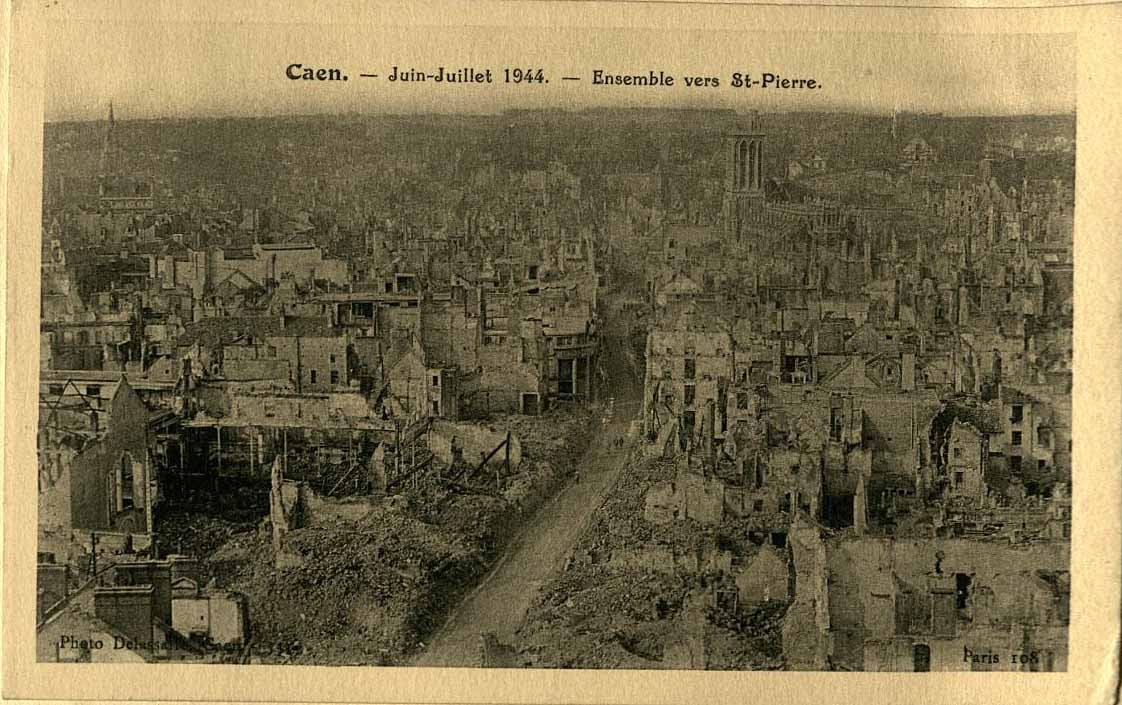

Aerial view of Caen after the bombings in July 1944 (Coll-164/4)

As you can see in the picture, the city was ravaged. The central area around the castle, St Pierre Church, and the neighbourhood called îlot St Jean were particularly affected. Post-war Caen looks like a field of ruins, and I was moved when I browsed the album for the first time and saw the full extent of the devastation. When it happened my grandmother, who was around 15 at the time, had taken shelter in a town a few kilometres away; but my grandfather was there and took part in the rescue effort to help searching the rubbles for survivors. He was only 18.

Looking through the album, I was able to recognise a few familiar buildings amid the destruction: churches, streets, houses, the castle… I knew exactly where these were and what they looked like now. I found the comparison really interesting, and this is why I decided to do a little before/after photo shoot when I went home for the Christmas holidays.

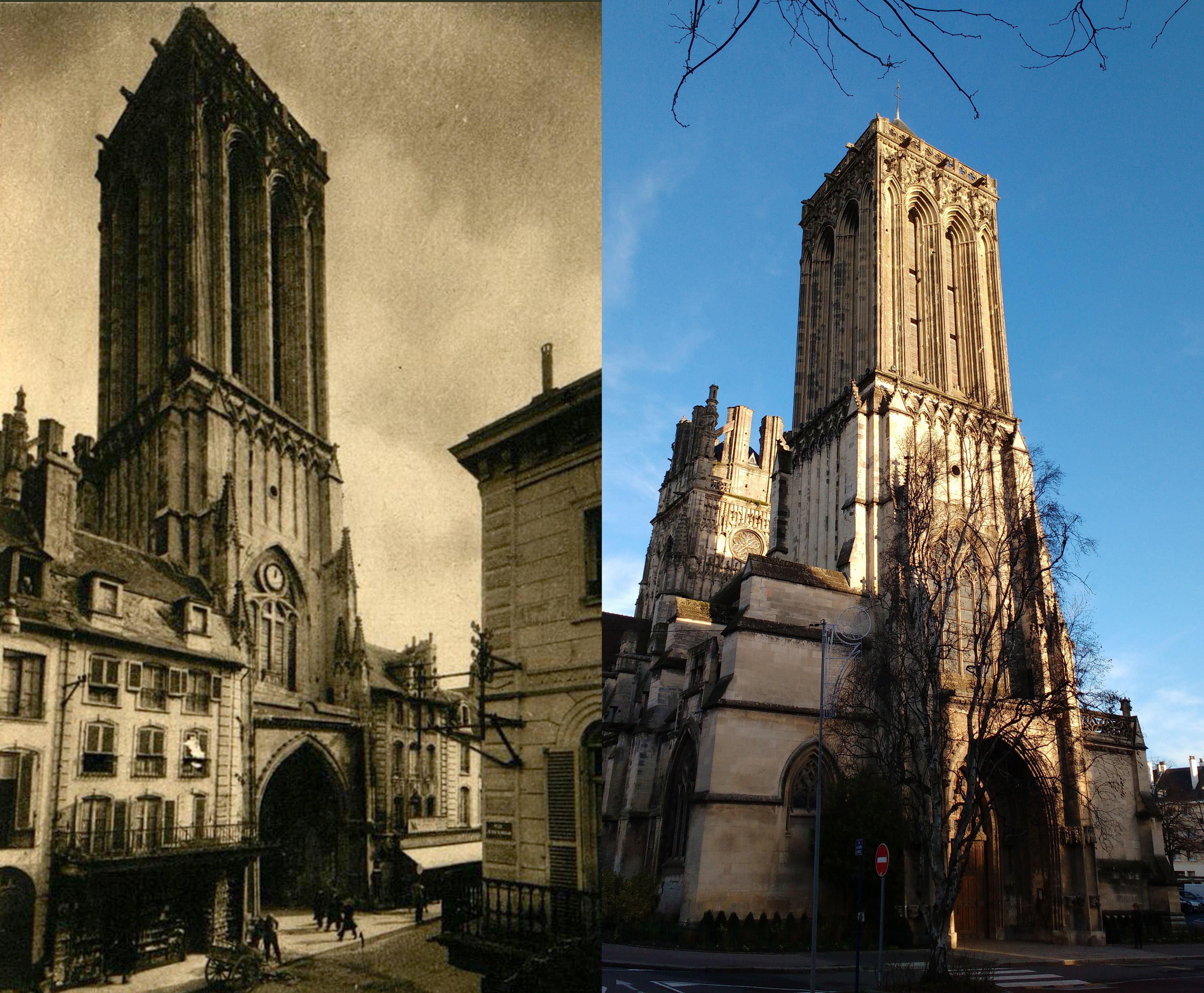

St Pierre Church and surrounding area (Coll-164/58)

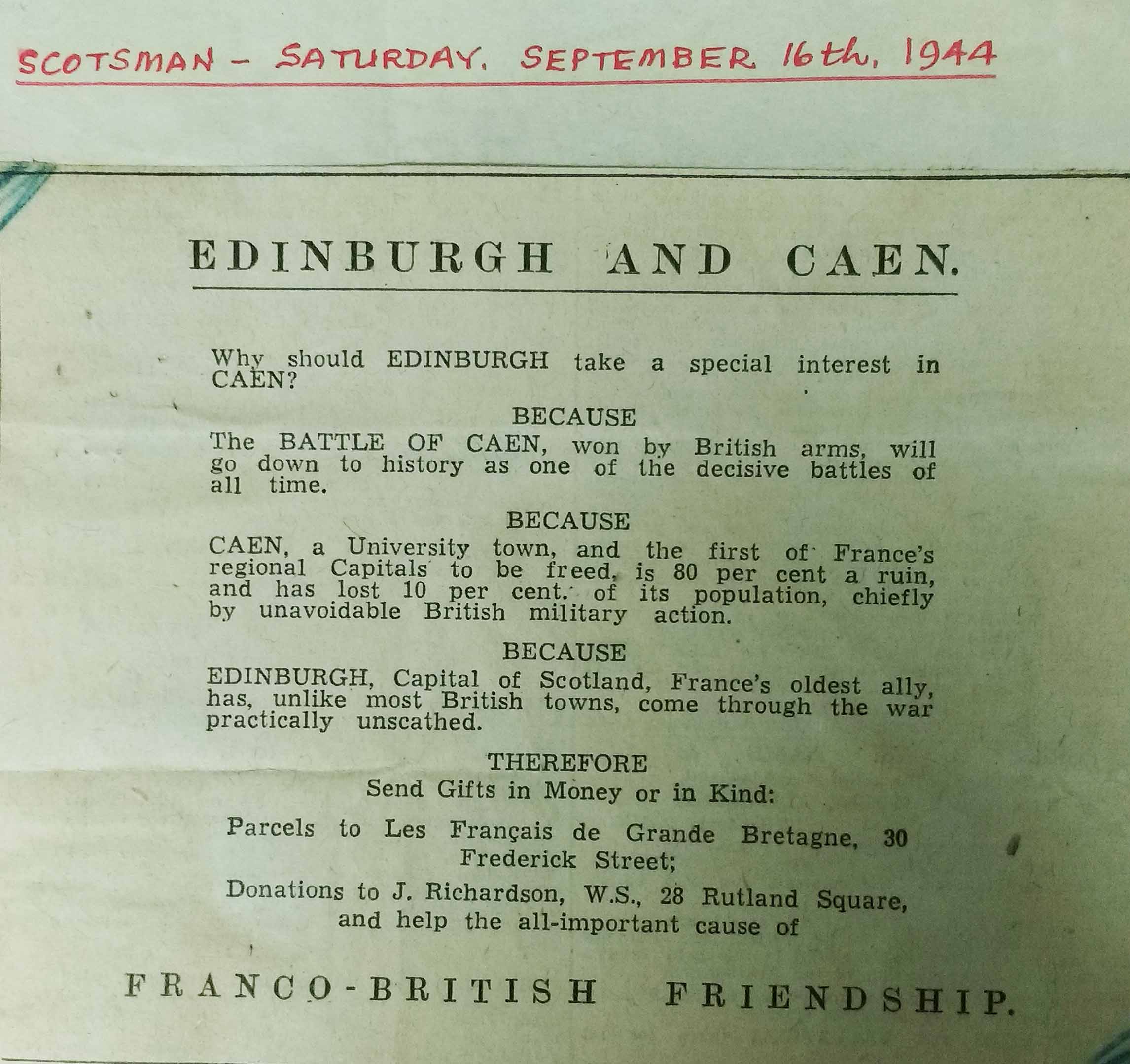

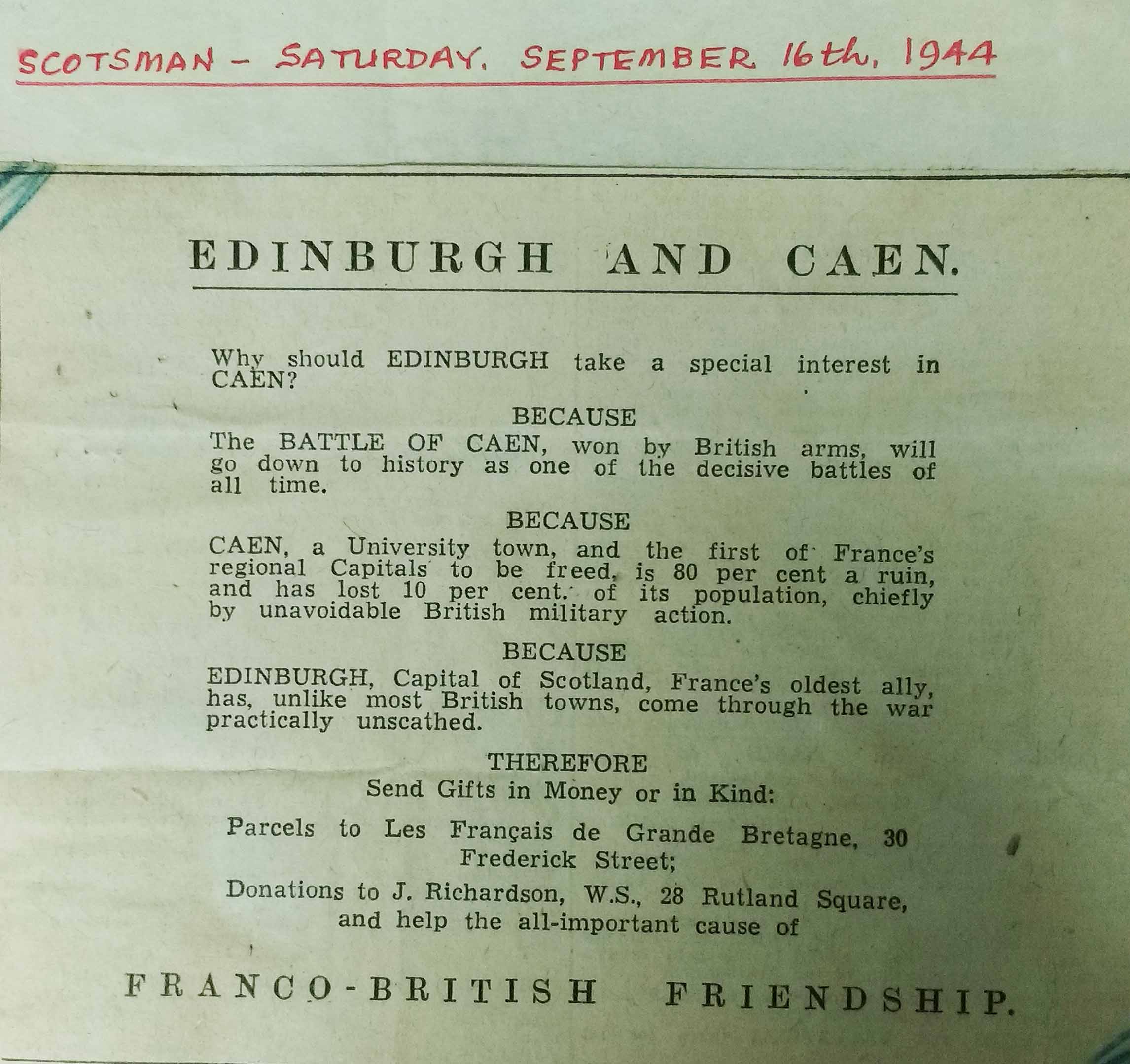

I started my little project on a sunny winter afternoon. Walking past my old university, I remembered that one of the nearby avenues was called ‘Avenue d’Edimbourg‘; and I finally understood why! Edinburgh was one of the cities that sent help and supplies to Caen after the bombing raid. The album is testimony to this connection: it was donated by John Orr, Professor of French at the University of Edinburgh and founder of the Caen-Edinburgh Fellowship. The latter was set up after the war to help the inhabitants of Caen by sending food, clothes, and supplies to the devastated city. John Orr himself organised for books to be sent to the library of the University, which was completely destroyed and had to be rebuilt from scratch, and for this he’s also had a street named after him.

Street signs named after John Orr.

Call for donations to Caen from the papers of Professor John Orr held in the Special Collections (Coll-77).

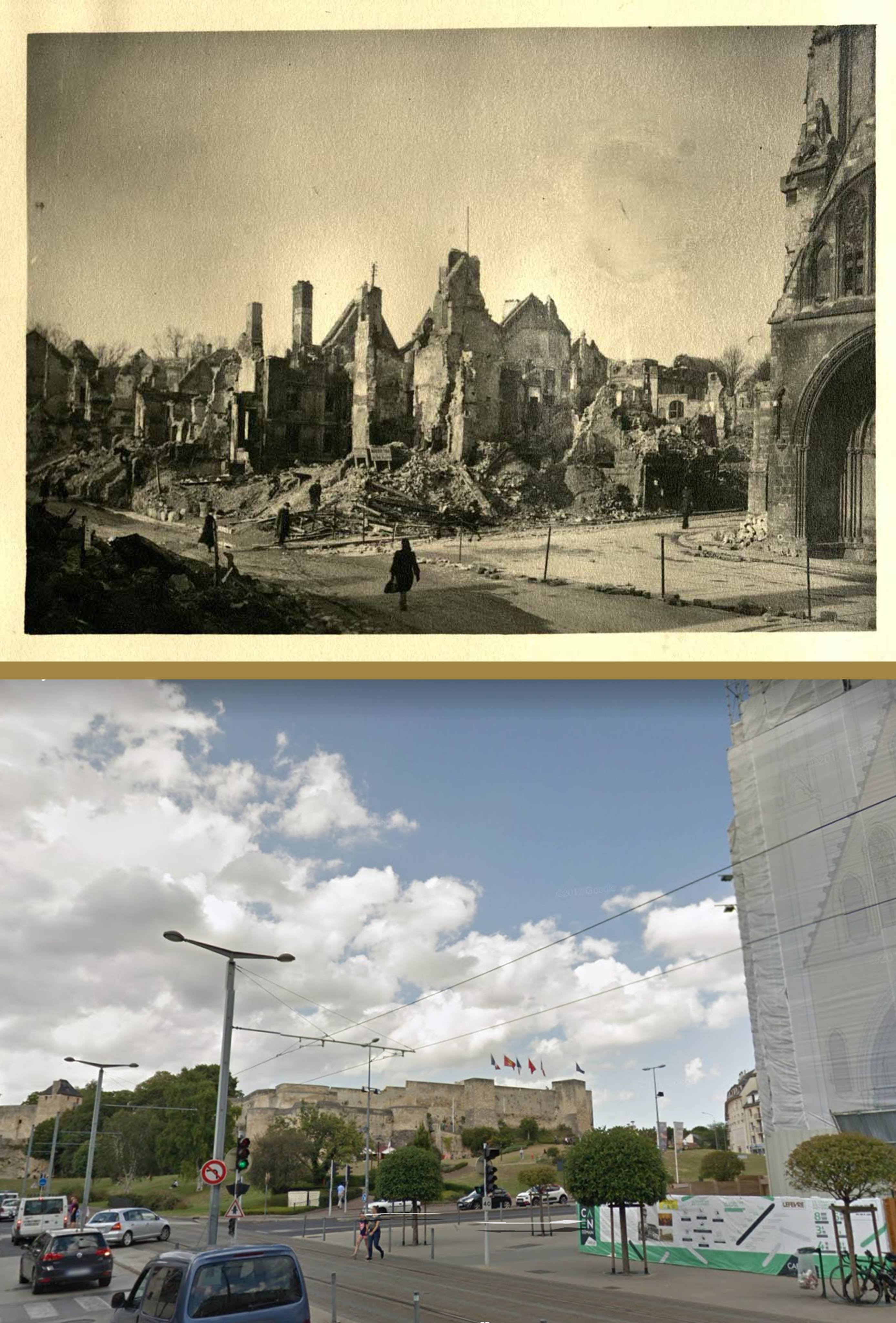

I soon arrived in the city centre. The most noticeable building in Caen is its massive castle, founded in 1060 by William the Conqueror. It was used as barracks between 1789 and 1945, and occupied by German troops during the War, which explains why it was targeted by bombings. Some buildings and parts of walls were damaged, but most of it survived in decent condition. The same cannot be said for the houses build alongside its walls…And so, after the clearing of the ruins, the castle reappeared, and it was decided to restore and showcase this millennium-old building that overlooks the city. The words of my grandmother came back to me: ‘We didn’t even know we had a castle because there were so many houses around it! After the war it came a bit as a surprise…’

Castle of Caen seen from St Pierre Church. The surrounding buildings which were hiding it for centuries were not rebuilt after the war. (Coll-164/61)

Maison des Quatrans. The buildings which were in-between the house and the castle have been destroyed. (Coll-164/71)

But not everything was completely destroyed in Caen! Our old town centre, the Quartier St-Pierre (‘St Pierre neighbourhood’), still has many original features. The Church, for starter – the tower was destroyed and then rebuilt, and is now being cleaned to restore its original white-yellowish colour, darkened by pollution. The buildings around it, however, went up in smoke. La Rue Montoire Poissonerie (Montoire Poissonerie Street), for example, has vanished.

St Pierre Church from Rue Montoire Poissonerie (now an apartment building). (Coll-164/11)

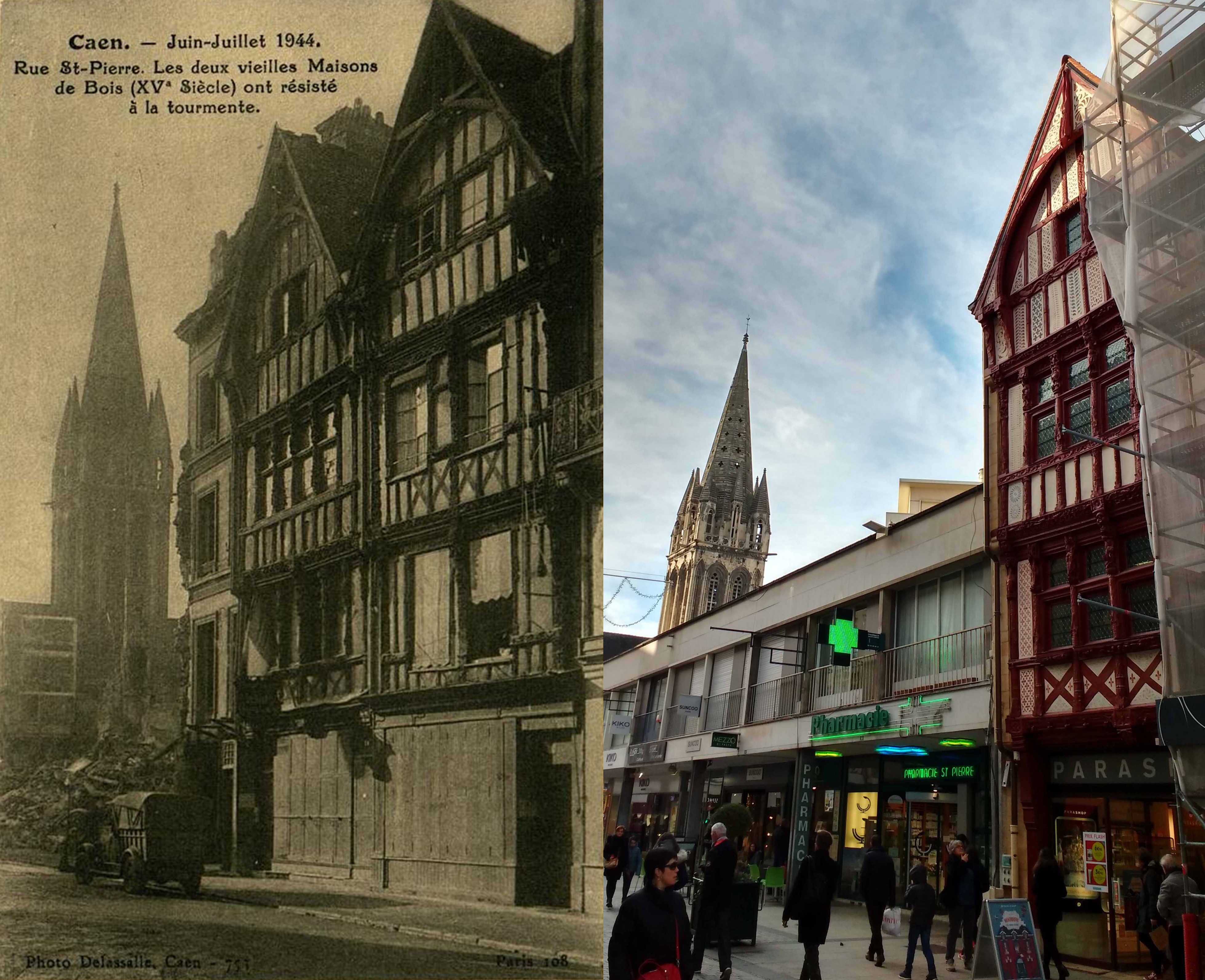

On the other hand, the main street of the neighbourhood, la rue St Pierre, has been more or less spared, and the old stands alongside the new. In the picture below you can see the busy Place St Pierre, full of shoppers and tourists, with the church Notre-Dame-de-Froide-Rue in the background and a beautiful half-timbered house from the 15th century. They miraculously survived, and are now being restored to get their lively colours back!

Place St Pierre and its 15th century half-timbered houses. (Coll-164/18)

Place St Pierre and Notre-Dame-de-Froide-Rue Church. (Coll-164/38)

As a medievalist, I still regret the loss of the Rue St Jean, a once beautiful street full of hôtels particuliers and ancient half-timbered houses just like the one in the picture above. One of the only original buildings still standing is the very curious Eglise Saint-Jean – which has the particularity of being completely wonky! Our very own modest Pisa Tower, which is leaning because Caen was built on unstable grounds. Everybody thought this fragile building would never last – little did they know it would be the only monument to survive the raid of St-Jean street.

Eglise Saint-Jean, which is much sturdier than it looks…(Coll-164/72)

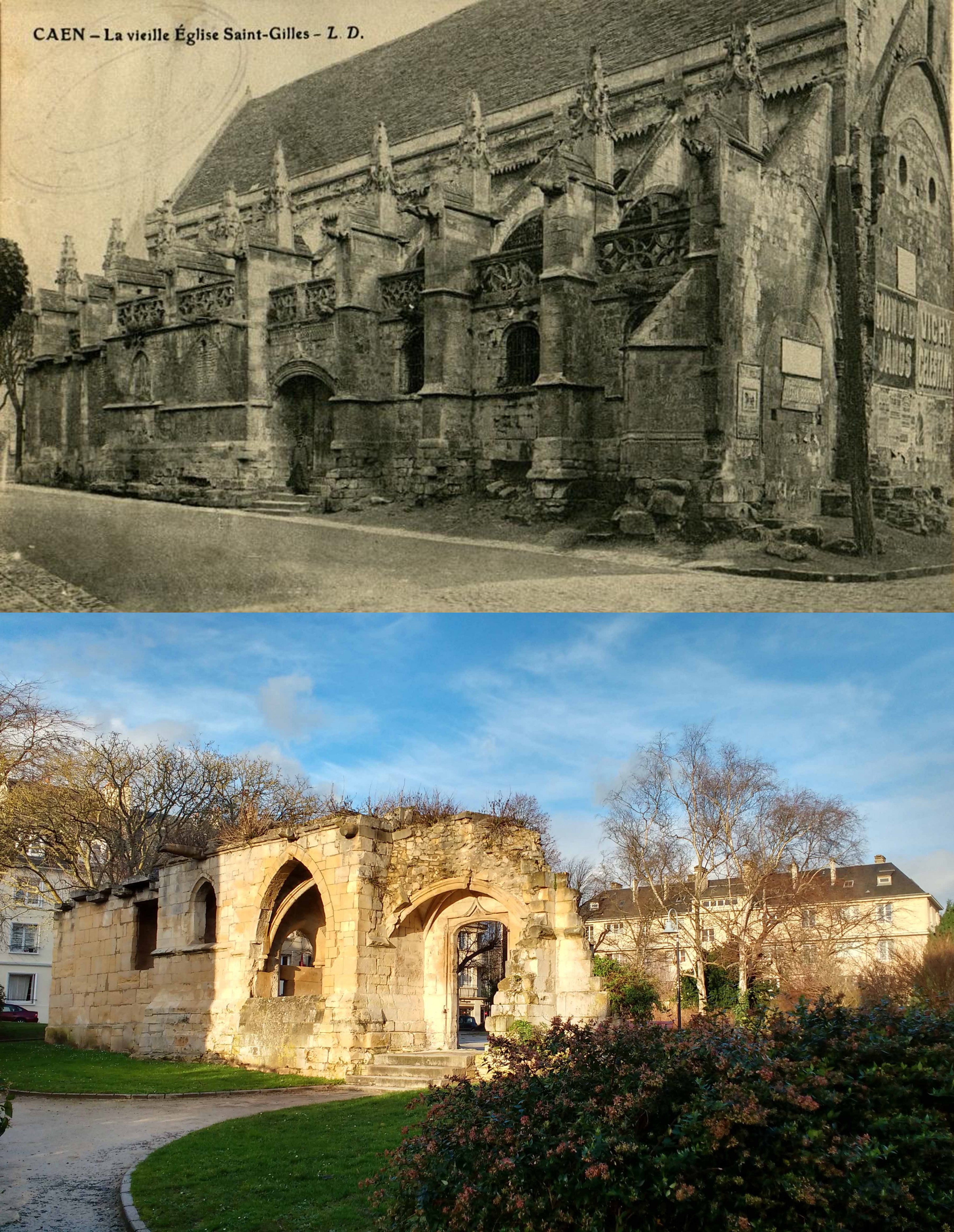

Sometimes, there was nothing to save but a section of wall, a half-collapsed doorway, the base of a pillar…left as a memory, a reminder of what the city had gone through:

Saint-Gilles Church, now a small park. The only recognisable feature is an archway. (Coll-164/36)

Saint-Julien Church before, during and after the bombings. (Coll-164/45 and Coll-164/48)

Like many French towns and cities, old Caen was full of narrow, dark medieval streets that would add a lot of charm to a city nowadays. I remember lamenting about the destruction of these quaint quarters – some of the largest boulevards in Caen have actually been shaped by American bulldozers –, and my grandfather replying: ‘it was dark and dirty before, very cold and inconvenient. It’s nicer now. They did a good job rebuilding everything’. The inhabitants rebuilt their home with the very typical Caen stone, which has a light and warm yellow colour, and the new blends in with the old. The city may not be as beautiful as other French towns spared by the war, but it is a nice place to live, where history has left its mark.

Our archivist doing some fieldwork…

Description of the album on ArchivesSpace: https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/312

Aline Brodin, cataloguing archivist, 6 June 2018.

Special thanks to Clément Guézais and Inès Prat for their help in taking and editing the photographs.