In 1951, students voting for a new Rector of Edinburgh University faced a choice between a quite extraordinary range of candidates. The election of actor Alistair Sym in 1948 had put an end to a long tradition of electing career politicians or military men. This time, in the wake of Sym’s success, nominees included Nobel-prize winning scientist Sir Alexander Fleming, novelist Evelyn Waugh, music hall entertainer Jimmy Logan, and politician and spiritual leader, Sir Sultan Muhammed Shah, Aga Khan III.

Also on the ballot was Lallans poet Sydney Goodsir Smith, who had come to prominence three years earlier through his collection Under the Eildon Tree, one of the major works of the Scottish Literary Renaissance. Edinburgh University Archives have recently purchased a copy of Smith’s campaign leaflet, adding to our major collection of Smith papers (Coll-497).

Smith was born in New Zealand but moved to Scotland in 1928 when his father Sir Sydney Alfred Smith (1883-1969) was appointed Professor of Forensic Medicine at Edinburgh University. Smith himself began a medical degree at Edinburgh University but soon abandoned it to study Modern History at Oxford. The ‘Message from the Candidate’ in the campaign leaflet alludes to his brief Edinburgh career:

During my short and somewhat hectic time as a medical student here, I must have been inoculated with the bug of not exactly ‘study’ so much as just ‘being a student’, for I seem to have remained a student, of one thing or another, ever since.

Smith thus presents himself as ‘a real student’s rector’, who, unlike his ageing and out-of-touch rivals, will provide an ‘effective student voice’ on the University Court. There is a second strand to his campaign, however, which voters may have struggled to reconcile with his stance as a spokesman for student interests.

The ‘Message from the Candidate’ also states that Smith’s nomination is:

single evidence of the increased regard held for Scottish literature – too long the Cinderella of Scottish life and thought – by the student body of what used to be Scotland’s capital in fact as well as name

The leaflet, in fact, foregrounds Smith’s literary credentials. The cover photo portrays Smith in his study, resplendent in a smoking gown, and surrounded by tottering piles of books. Beneath the caption ‘Sydney Goodsir Smith: Poet, Scholar, Artist, Wit’ are endorsements from major literary figures of the day, Edith Sitwell, Neil M. Gunn, Duncan Macrae, Sorley Maclean, and Hugh MacDiarmid.

Conspicuously, the least political endorsements are placed first. Sitwell claims that ‘it would honour poetry should [Smith] be elected’, Gunn declares that ‘to vote for a Scots poet of so rare a vintage as Sydney Goodsir Smith I should find irresistible’. For actor Duncan Macrae, Smith is alone among the candidates in possessing ‘the distinction of genius’. Maclean too credits Smith with ‘creative genius’ along with an ‘irresistible personality’ and a place among ‘the very finest critical intelligences’.

Only the final endorsement from Hugh MacDiarmid, himself a rectorial candidate in 1935 and 1935, gives a hint of Smith’s political position. Presenting Smith as ‘an outstanding figure in the Scottish Renaissance Movement’, MacDiarmid describes him as:

A scholar, a lover of all the arts, a great wit, a well-informed Scot with all his country’s best interests at heart and above all a passionate concern for freedom and hatred of every sort of cant or humbug, he typifies all that is best in the Scottish National Awakening now in progress and is contributing magnificently thereto.

The rest of the leaflet does not so much explain how a commitment to the Scottish Literary Renaissance will shape Smith’s rectorial work, as set the two strands of his campaign side-by-side, leaving the voter to trace a connection. For example, it gives the following ‘Four Reasons for Supporting Sydney Goodsir Smith’:

- His distinction is that of real creative genius.

- He would be sure to give a worthwhile and amusing address.

- He is a Scotsman who believes in his own country.

- He would be a real students’ rector.

In places, the leaflet is a little self-contradictory. Students are asked to vote for Smith because ‘a Scottish university should first of all honour the great men of its own country’. They should not vote for Fleming, however, because he may be ‘a great scientist and benefactor of mankind’ but the ‘rectorship is an office of spokesman for the student body, not an honour per se‘.

Perhaps, in fact, the strongest claim that emerges from the leaflet is the likelihood of Smith delivering a colourful rectorial address. His credentials as ‘wit and humorist’ are illustrated in a series of put-downs of rival candidates. Particularly acerbic barbs are directed at Jimmy Logan (‘information scanty but supposed to be a comedian’), politician Sir Andrew Murray (‘nicely groomed ex-provost … non-allergic to limelight’), Evelyn Waugh (‘hobby – writing blue books for naughty, naught Catholics’), and the Aga Khan (‘but who can’t?’).

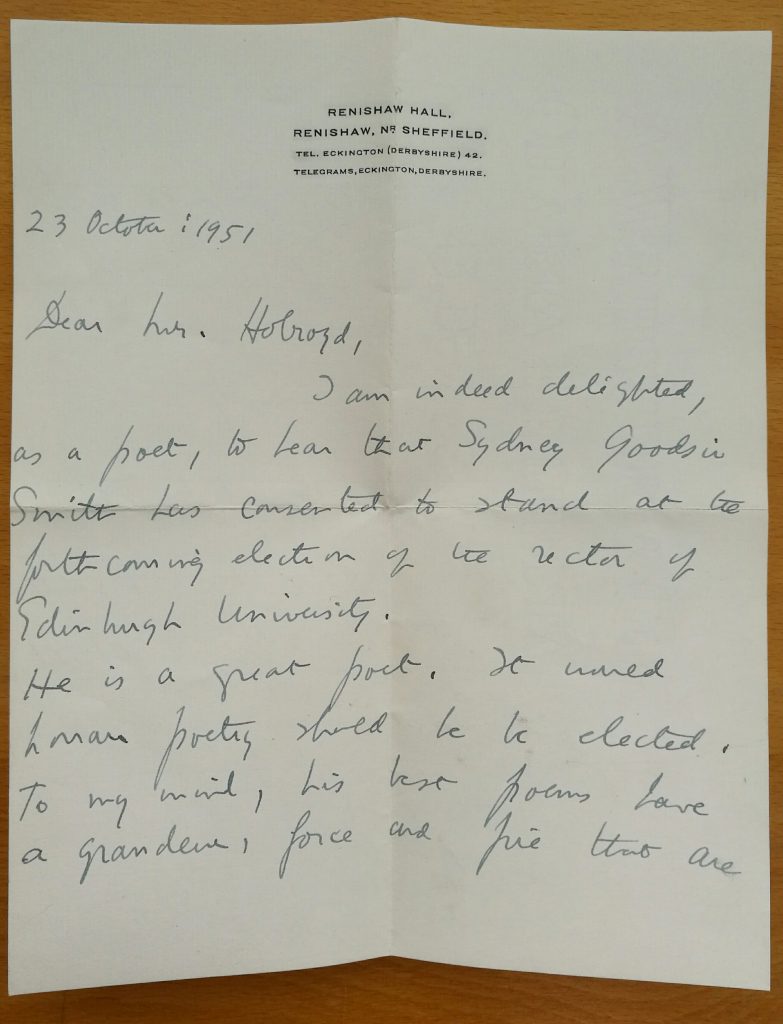

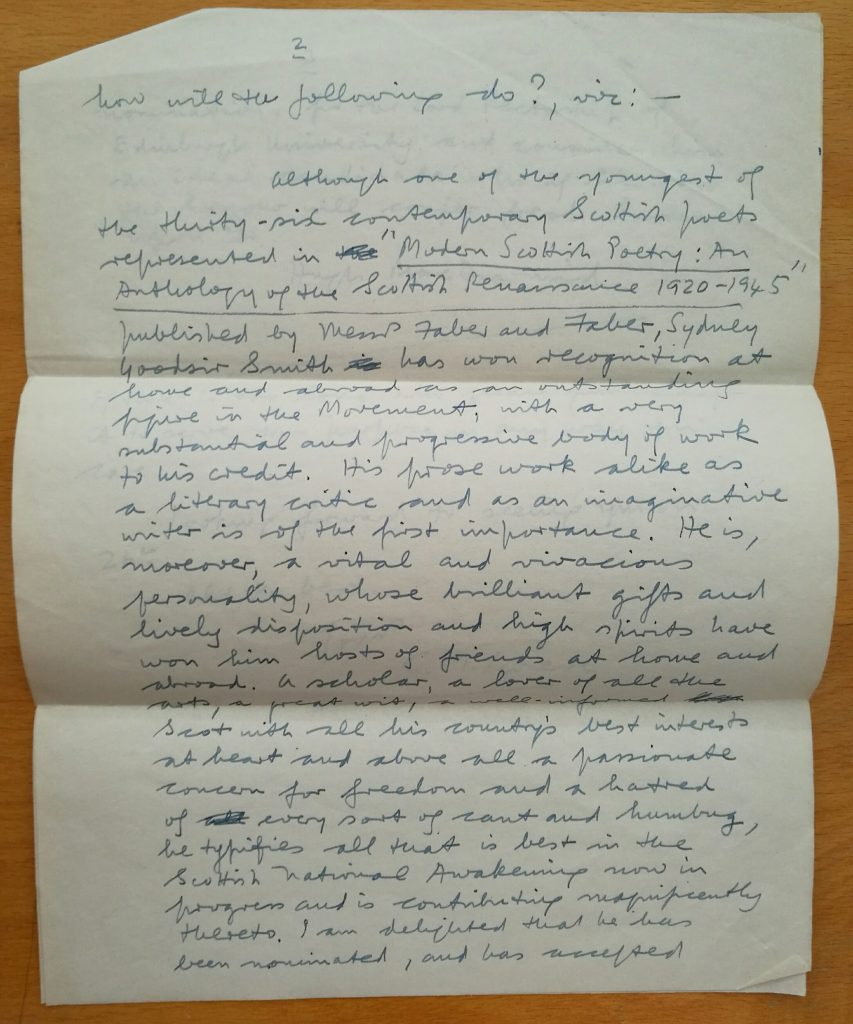

Since acquiring the leaflet, we have discovered that another recent purchase, the archives of the Edinburgh student literary magazine The Jabberwock (Coll-1611), contains a draft version of Smith’s ‘Message from the Candidate’, together with the original manuscripts of the endorsements by Hugh MacDiarmid and Edith Sitwell. The Jabberwock’s editor Ian Holroyd evidently worked as Smith’s campaign manager, and the archive also contains a letter from veteran Scottish writer Compton Mackenzie, regretting that he cannot endorse Smith’s candidature, as he has been approached by two other candidates with equal claims on his support.

- Letter from Edith Sitwell

- Letter from Hugh MacDiarmid

The draft of Smith’s ‘Message from the Candidate’ contains a substantial amount of text omitted from the published version. One deleted paragraph reads:

If this were a political election (which I am told it is not to be, this time), I think my sentiments would be well-known to some of you as those of a man who wished to restore the ancient dignity of Scotland – all-out, in fact, and only falling somewhat short of bombs in letter-boxes and Customs at the Border. However, as this is not to be political, and as we are unfortunately unlikely as yet to get the chance of reducing the tax on whisky, I come to you with no ‘policy’ at all. I have none, in the circumstances, for I believe it would not be proper (in the happy event of my election) or my place to represent any other body than the students of this University and to be their spokesman on the University Court.

Was it the hints of political extremism, the allusion to Smith’s drinking habits, or the cheery admission of having no policy, that most alarmed Smith’s campaign manager? Also deleted is the postscript ‘I am truly sorry Groucho refused – he’d have unstuffed a few more shirts’. Groucho Marx had, in fact, been asked to stand as a rectorial candidate, but sadly declined.

In the end, Sir Alexander Fleming, who enjoyed the near unanimous support of medical students, won a resounding victory. Smith’s backers may over-estimated the average Edinburgh student’s interest in literature. Canvassers for Evelyn Waugh commonly met with the response: ‘Who’s she?’

For more on the 1951 Rectorial campaign, see Donald Wintergill, The Rectors of the University of Edinburgh 1859-2000 (Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press, 2005), pp. 127-35. Although Smith was never to stand again, his father Sir Sydney Smith won the next Rectorial election in 1954.

Paul Barnaby, Acquisition and Scottish Literary Collections Curator