An unpublished letter from Mary Poppins author P. L. Travers to Hugh MacDiarmid in Edinburgh University’s C. M. Grieve Archive casts further light on the surprising relationship between the two writers revealed in an article in today’s The National. Our letter shows that Travers was so taken by MacDiarmid’s writing that she urged her publisher to bring out an edition of his selected poems.

Jennifer Morag Henderson‘s essay in The National (‘Poppins and MacDiarmid – Truly Whaur Extremes Meet’) reveals that MacDiarmid and Travers met in London in 1931 or 1932, probably under the aegis of Irish writer and mystic George William Russell (1853–1919) who wrote under the pseudonym ‘AE’. Russell was something of a spiritual and literary mentor to Travers, who was then working as a journalist and drama critic, but he also contributed an ‘Introductory Essay’ to MacDiarmid’s 1931 collection First Hymn to Lenin and Other Poems.

Jennifer Morag Henderson‘s essay in The National (‘Poppins and MacDiarmid – Truly Whaur Extremes Meet’) reveals that MacDiarmid and Travers met in London in 1931 or 1932, probably under the aegis of Irish writer and mystic George William Russell (1853–1919) who wrote under the pseudonym ‘AE’. Russell was something of a spiritual and literary mentor to Travers, who was then working as a journalist and drama critic, but he also contributed an ‘Introductory Essay’ to MacDiarmid’s 1931 collection First Hymn to Lenin and Other Poems.

As Henderson notes, the meeting is recorded in a published letter from MacDiarmid to another Irish writer Oliver St John Gogarty, dated 22 January 1932, where he writes: ‘The lady with the pheasant-coloured hair [Travers] is quite a figure in Bloomsbury circles. We have had some most amusing times together – and would have had more but for the horrible tangle of my own affairs (the divorce went through last Saturday).’ Henderson wonders whether the pair discussed their conflicting views on nationalism or their mutual interest in Soviet Russia (which Travers was to describe in her book Moscow Excursion). She concludes, however, that during MacDiarmid’s messy divorce from Peggy Skinner, Travers probably interested MacDiarmid ‘as a woman first and writer second’.

The letter from Travers in our Grieve Archive (Gen. 2094/5 f. 2325), apparently overlooked by editors of MacDiarmid’s correspondence, confirms Henderson’s conjectures as to mutual areas of interest but also suggests that their relationship had a strongly literary character. The letter is undated. A reference to MacDiarmid’s First Hymn to Lenin which Travers ‘would love to have … some day’ might place it in the 1931-32 time-frame discussed by Henderson. The fact, however, that Travers clearly already has a strong relationship with publisher Gerald Howe, who published the first Mary Poppins book in 1934, makes the mid-1930s a more probable date.

The letter from Travers in our Grieve Archive (Gen. 2094/5 f. 2325), apparently overlooked by editors of MacDiarmid’s correspondence, confirms Henderson’s conjectures as to mutual areas of interest but also suggests that their relationship had a strongly literary character. The letter is undated. A reference to MacDiarmid’s First Hymn to Lenin which Travers ‘would love to have … some day’ might place it in the 1931-32 time-frame discussed by Henderson. The fact, however, that Travers clearly already has a strong relationship with publisher Gerald Howe, who published the first Mary Poppins book in 1934, makes the mid-1930s a more probable date.

Travers writes that ‘I have been to see Howe and with every sweet and noble adjective at my command put your suggestion of the 50-100 of your very finest selected’. Howe was ‘definitely interested’ but ‘would not commit himself’. He invites MacDiarmid to submit a selection of verse, either directly or through Travers, but on the understanding that Howe is not ‘bound in any way’. Travers confides that Howe ‘knows nothing in the world about poetry’ and depends entirely on advice from an unnamed writer who, fortunately, is a good personal friend of Travers and whom she believes she can influence in MacDiarmid’s favour.

Travers repeatedly stresses her personal enthusiasm for the project (‘Personally I think the idea such a good one!’) and mentions that Howe had particularly liked the suggestion that W. B. Yeats might write an introduction to the MacDiarmid volume.

In the rest of the letter, Travers mentions that ‘AE’ has dined with her the previous night, and that they had talked about MacDiarmid. She also mentions an article that she is writing on ‘Nationalism and Internationalism’, hinting at the political differences between the pair mentioned in Henderson’s article. While MacDiarmid, of course, combined revolutionary socialism with Scottish nationalism, the Australian-born Travers considered herself a citizen of the British Empire. Here she remarks that the concepts of nationalism and internationalism surely ‘don’t exist on other stars’.

The anthology of MacDiarmid’s selected poems never appeared. Travers mentions Gerald Howe’s fears that, as a poet, MacDiarmid might be tied to his original publisher Victor Gollancz ‘the “cutest” drafter of an agreement in London’, and perhaps that effectively stymied the project. The letter is nonetheless a record of what was clearly a warm literary friendship between figures from what one might have thought were very different worlds.

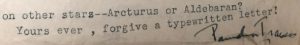

Signature of P.L. [Pamela] Travers