Last summer, I spent five days photographing the skeleton of William Burke to document recent conservation as a record for future collection care. The remains had been conserved and cleaned for the first time since the 1800s and the skeleton was going on display at the National Museum of Scotland for their 2022 exhibition “A Matter Of Death and Life“. I also photographed the life and death masks of Burke, Hare and Robert Knox (“the man who buys the beef”).

I.C.28 is part of a 19th century numbering system for the skull collection at the University of Edinburgh’s Anatomical Museum. This working educational museum hosts extensive anatomical objects which are still currently used in teaching. I.C. means ‘British Irish’ (in the days before the Republic) and 28 means it’s the 28th Irish skull to be accessioned into the collection.

Photographing human remains is never an easy thing to do. There is a constant reminder of the fragility of the material that makes up our bodies and, layered on top of that feeling, is the fact that this person took the lives of other human beings for money – sixteen in total, that we know of.

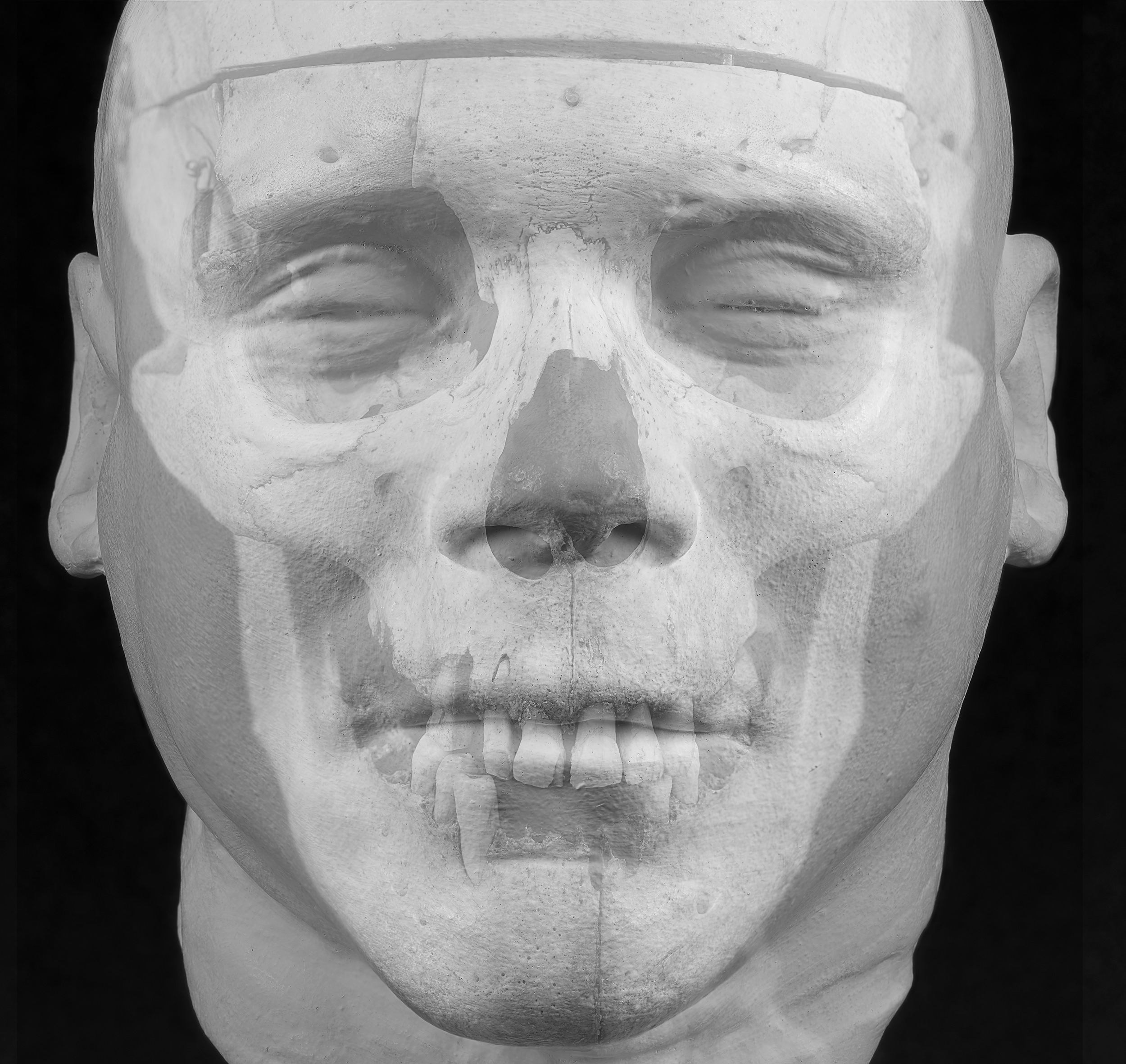

Although this work was carried out at the request of the University, my own curiosity drove me to explore the possibility of a forensic composite matching the skull to the physical death mask. I have followed the police use of forensic composites in the past to identify human remains, and the result of this experiment can be seen in the photograph introducing this post. This image has already been used in talks by the anatomy curator when discussing the collection.

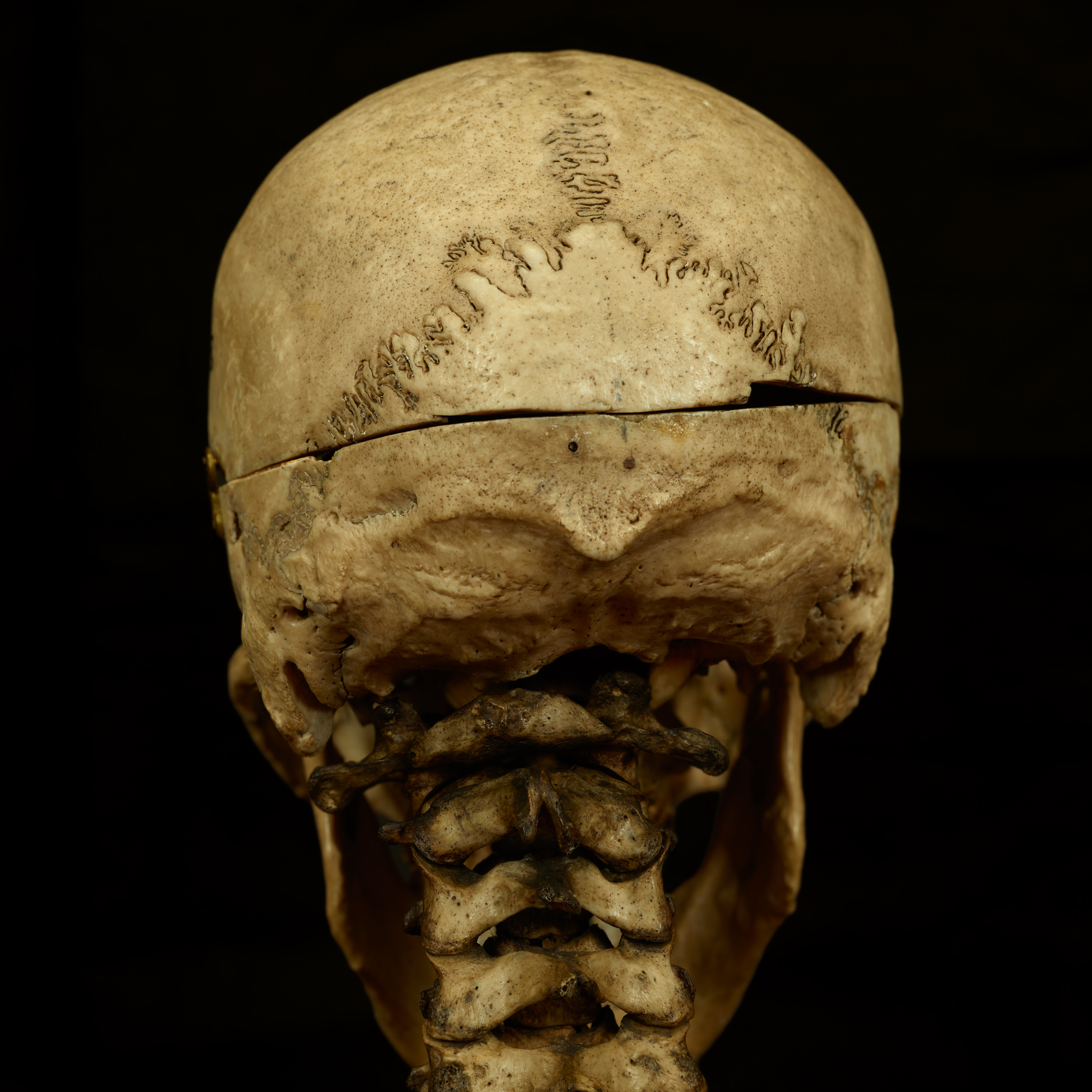

New camera and lens technology allows remarkably rich detail capture and I focus stacked a number of the images for research documentation. I used a PhaseOne IQ3 camera with a Macro lens for the focus stacking element: this was the first time our team had used this camera in an untethered shoot on location . I was assisted in moving the skeleton from its glass case by Malcolm MacCallum, the curator of the Anatomical Museum. We also removed the skull from the torso in order to photograph inside it for the first time.

It was essential to capture the neck portion in detail, as there has been a lot of speculation around whether Burke’s neck was broken when he was hanged for his crimes. It is clear from the photography that his neck bones remained intact, indicating that rather than a quick end to his life, Burke most likely suffocated slowly.

The murderous hand of William Burke.

Burke’s modus operandi, using his hands and knees to suffocate his victims, led to the forensic term “Burking”:

“‘Burking’ is a method of homicidal smothering with traumatic asphyxia. The term ‘Burking’ is derived from notorious criminal ‘Burke’, who with his accomplice ‘Hare’, killed old people by a combination of smothering and traumatic asphyxia, and sold the bodies to the medical school in Edinburgh.”1

As challenging as it is working on anatomy collections, it is rewarding to add to accumulated resources for teaching and learning. It feels important to contribute to research, albeit in a supportive role. The history of medicine in Scotland is fascinating, if somewhat gruesome at times, and I feel privileged to work with these astounding collections and to make that very real point of contact with history.

Malcolm Brown, Photographer.

Sources:

- Prasad, D.D. ‘Burking: A Case Report’, Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences, Vol.3, Issue 39, (2014). Accessible here: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA467680885&sid=googleScholar&v=2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=22784748&p=AONE&sw=w&userGroupName=anon%7E2438bd11

Fascinating, thank you.

In 2013, I was given special permission to photograph the Burke and Hare artifacts in the anatomy museum.

The case was opened for me and I too examined the cervical vertebrae and saw no sign of a hangman’s fracture. I also saw that Burke had obviously been a short man in life. Recently, Malcolm MacCallum kindly verified that the veretbrae are undamaged and that Burke was measured as being 4ft 4 1/2in tall, post the current articulation of the skeleton.

One aspect I took particular note of lay in the life and death masks. I spotted that there are two masks from Burke. As far as I know, one is a life mask and the other was taken post execution. It seems to me that in the latter, Burke looks ten years younger, which makes sense given the circumstances.

I’ll be ineterested in hearing any thoughts you have on this.

Many thanks, David

Hi David,

Thank you for getting in touch. I was specifically asked to photograph the neck by Malcolm MacCallum to settle the debate around Burkes neck being broken during the drop from hanging. Its incredibly grim that he probably died slowly from suffocation.

I agree Burke does look younger in the death mask. His head was shaved which can make people look younger. I agree though that the death mask probably made him look more serene than the life mask. The issues he faced no longer a concern in death.

Photographing human remains is always challenging. In this case I was reminded of the fragility of the material that makes up our bodies. Respect for a former living human is also crucial. On top of all that Burke did take the lives of other human beings for profit. It was a complicated task to photograph Burke.

I do enjoy the historical element and above all else the point of contact with history whilst working with these fascinating collections.

Kind Regards,

Malcolm Brown.