For several months now I have been working as a Digitisation Operator at our studio in the main University library, and that time has flown by. A large part of my job is to take care of orders that come into the Cultural Heritage Digitisation Service (CHDS), which will often be requests from academics or researchers who require a digital copy of something from our collection. This means that I get to see a fantastic cross-section of what we have here, on a daily basis. This will usually be books, pamphlets, letters – any paper-based object that can sit safely on the scanner, and where the digitised copy doesn’t need to be publication-quality as this would be done on the high-quality cameras at a higher charge.

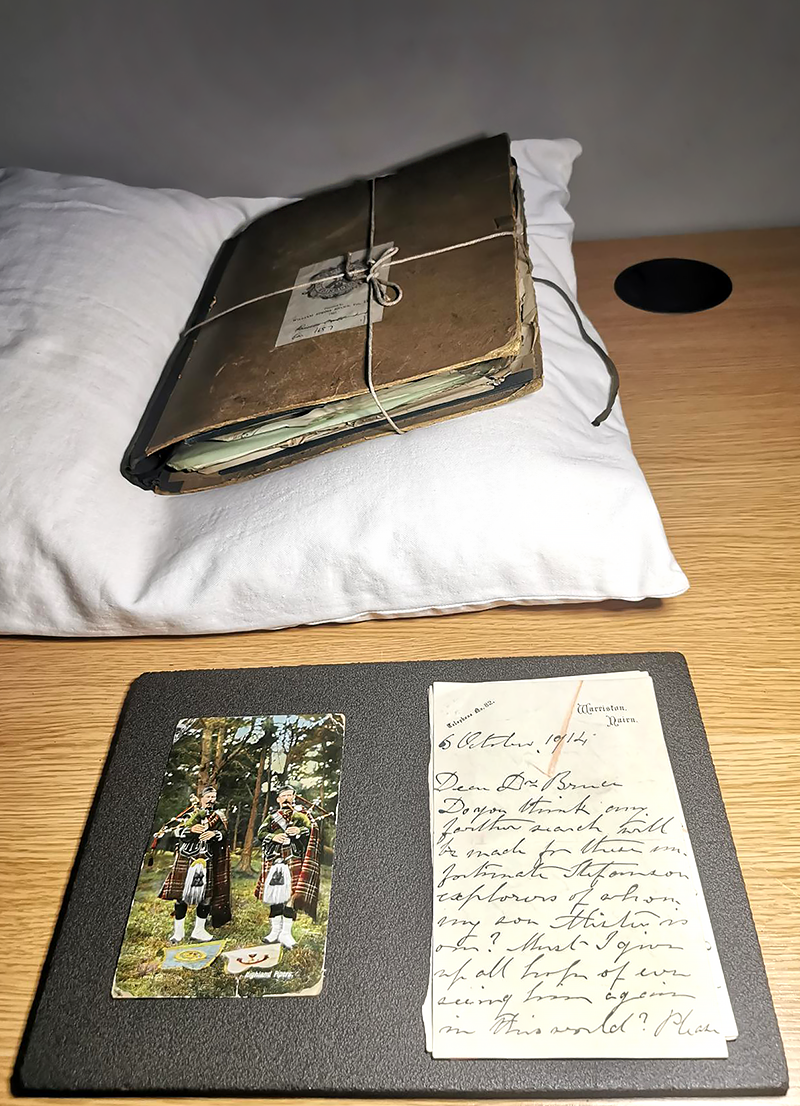

A recent favourite of mine was a set of letters and ephemera relating to a doomed Arctic expedition that set off from the west coast of Canada in June 1913, led by Canadian anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson, and captained by American explorer Robert Bartlett. This was to be the last voyage of the Canadian ship, the Karluk.

K.G. Chipman, Library and Archives Canada, 1974-325.

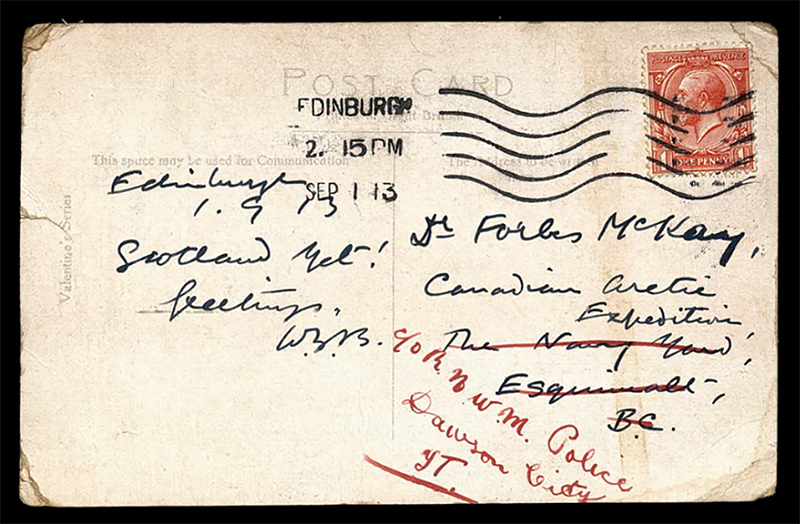

Though the geographic and scientific expedition was primarily Canadian-funded, there were team members on board from various countries including Scotland, which explains why the letters form part of our collection. More specifically, they formed part of the collection of William Speirs Bruce, explorer and geographer, whose papers were donated to the University in 1921.

His connection to the expedition was that he had recommended 24 year-old Glaswegian science teacher, William Laird McKinlay, to be taken aboard, and was in contact with several members of the crew regarding the expedition. McKinlay was joined by two other Scots: physician and biologist Alistair Forbes Mackay; and James Murray, biologist and oceanographer.

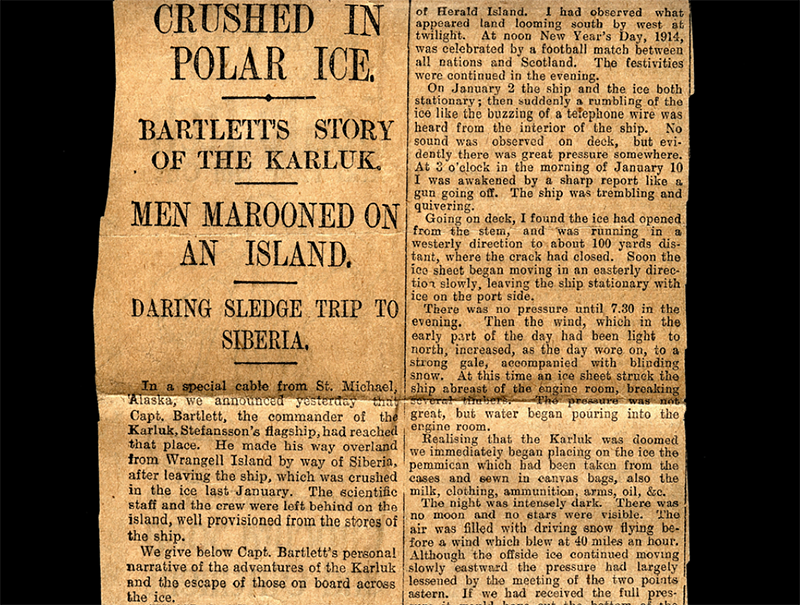

Two months into the expedition the vessel became frozen in heavy sea ice and was forced to drift off course. At the mercy of the ice for several months, they eventually became still for a few days. Stefansson then made the decision to head out with a small group in search of caribou to hunt. They were unable to find the ship on return however as it had drifted further again in strong winds, and so they carried on by dog sled to eventually reach Alaska.

The Karluk continued to drift until January 1914 when it eventually sank due to ice damage on the hull. Fortunately, there had been enough time to unload and store several months’ worth of supplies inside igloos constructed on the surrounding ice. Capt. Bartlett intended on staying put until daylight returned in February, as many of the crew were inexperienced in traversing Arctic terrain, let alone in the relentlessly dark winter months.

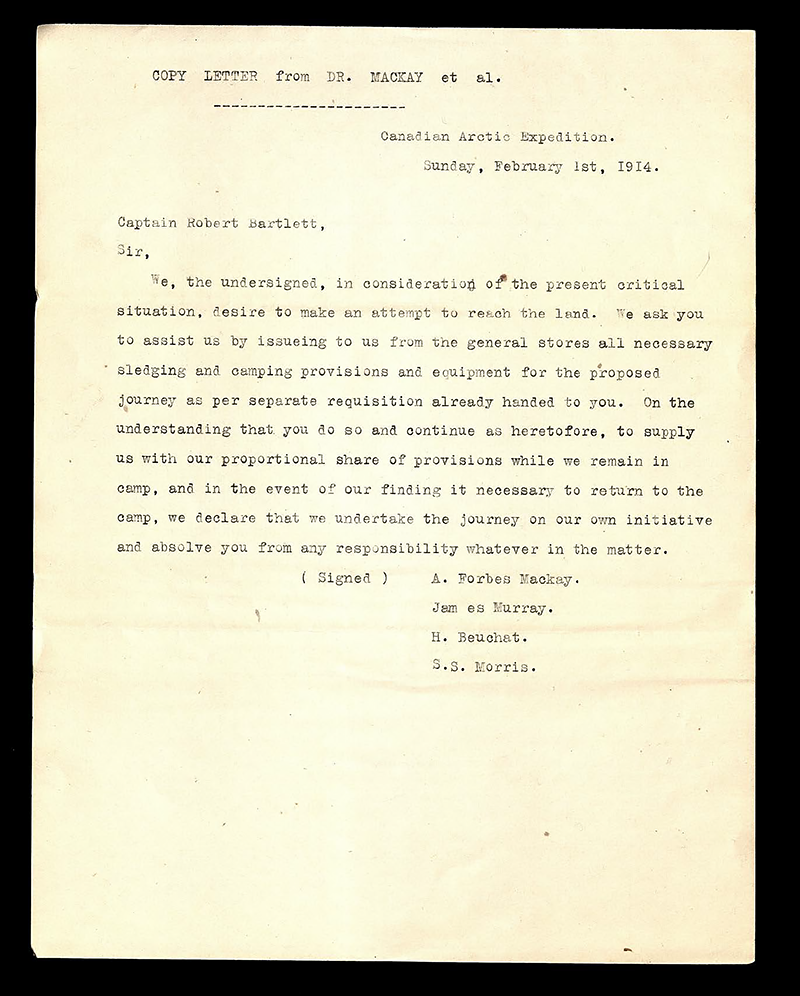

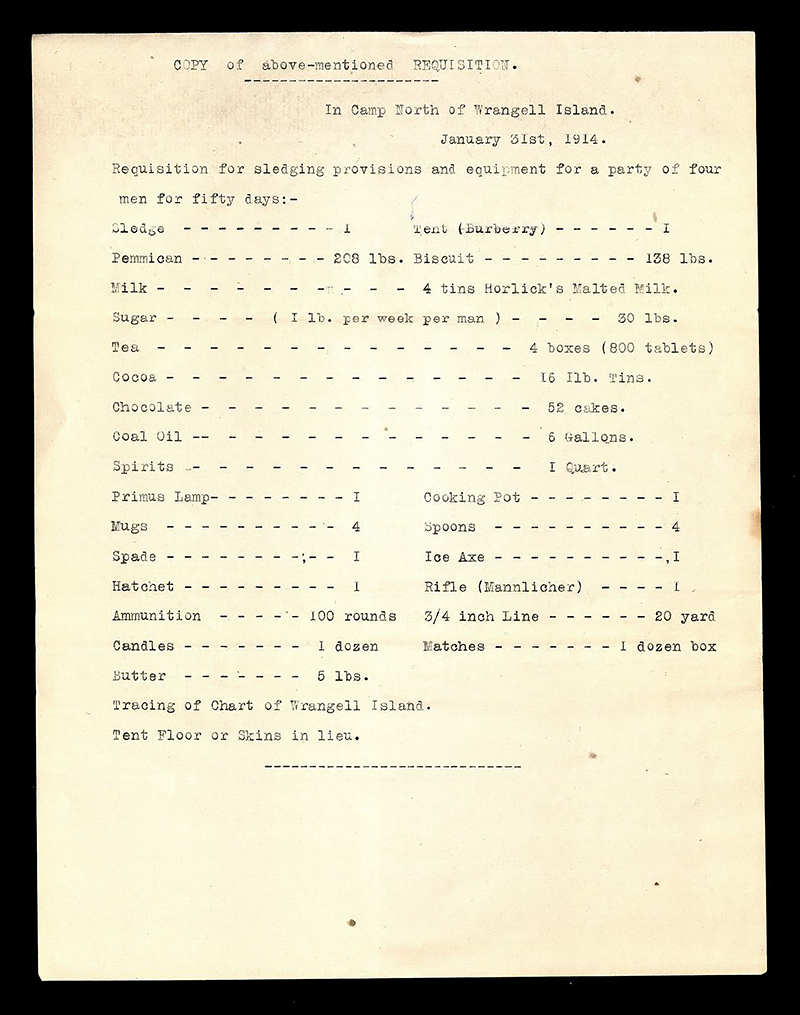

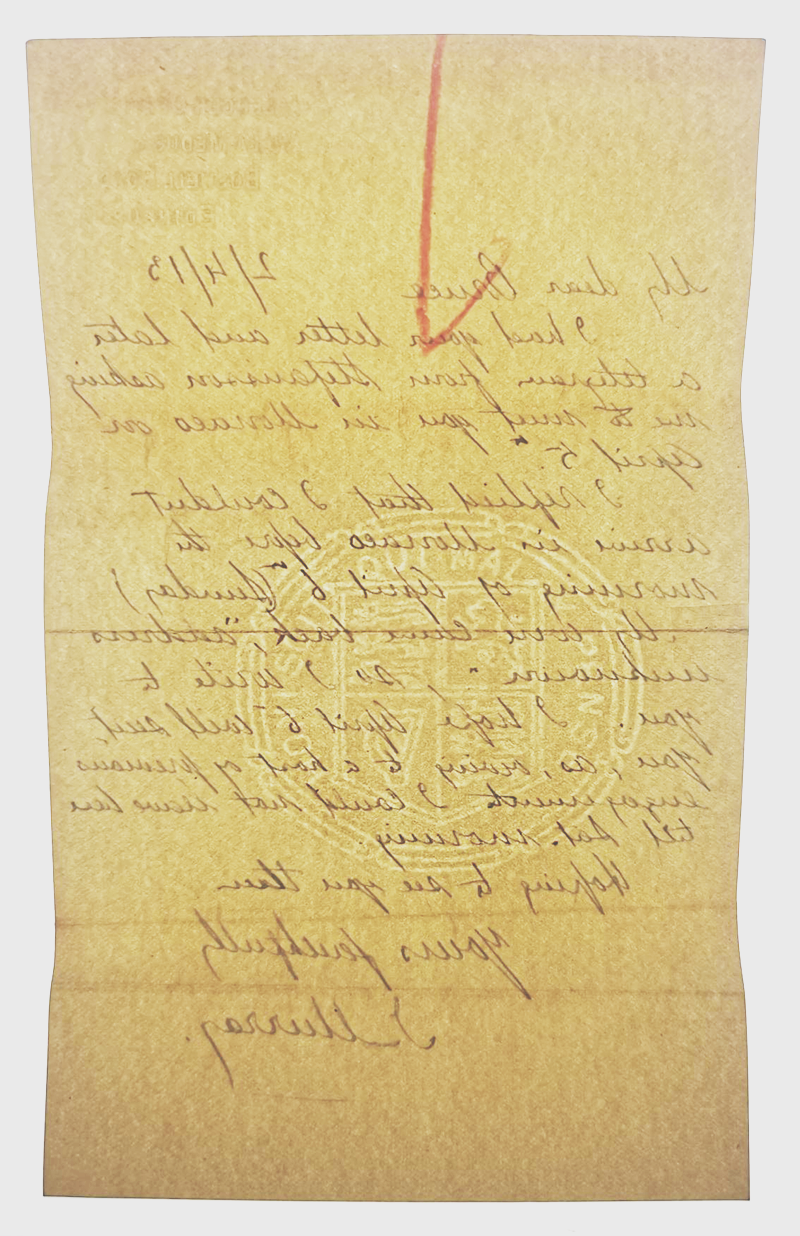

In disagreement and eager to seek land as soon as possible was Charles Forbes Mackay, joined by oceanographer James Murray; anthropologist Henri Beuchat; and seaman Stanley Morris, who all set out the following day. The images below show copies of the group’s request for 50 days-worth of supplies, and the letter written to Bartlett in return which absolved him of any official responsibility for their fate. They were witnessed several days later in a distressed state but refused to return to camp, and from that point were never seen again.

In total, eleven members of the original expedition crew of around 25 perished under various circumstances.

Despite the letter, Capt. Bartlett was heavily criticised in professional spheres for allowing the group to split from the ice camp at all. In the press, among the public, and the survivors however, he was hailed as a hero for ensuring the survival of the remaining crew under such dire straits.

With a collection so varied, each order in turn brings its own unique challenges to the digitisation process. In this case, some of the paper was so thin that it did not scan well on the black scanning bed. To rectify this, a sheet of acid-free white paper was placed behind to balance the look of the page, ensuring that it presented in its digital form as close to its physical form as possible.

Care must also be taken in handling the paper when it is particularly thin or deteriorated, and so it is essential to follow all advice given by our colleagues in the Centre for Research Collection’s conservation department. Despite what you may have seen on TV, gloves are a no-no – as long as hands are freshly washed it is preferable to touch paper objects with bare hands because wearing gloves decreases the sensitivity in your fingers needed to handle delicate sheets without damaging them. There are always exceptions however: if a page or binding has metal work, for example in the form of gilding, you must wear gloves as metals are far more susceptible to deterioration from the natural oils in your skin.

Another tip to remember is to always hold the paper from the sides, being careful where possible to not to touch any printed or written sections as ink is also more susceptible to deterioration.

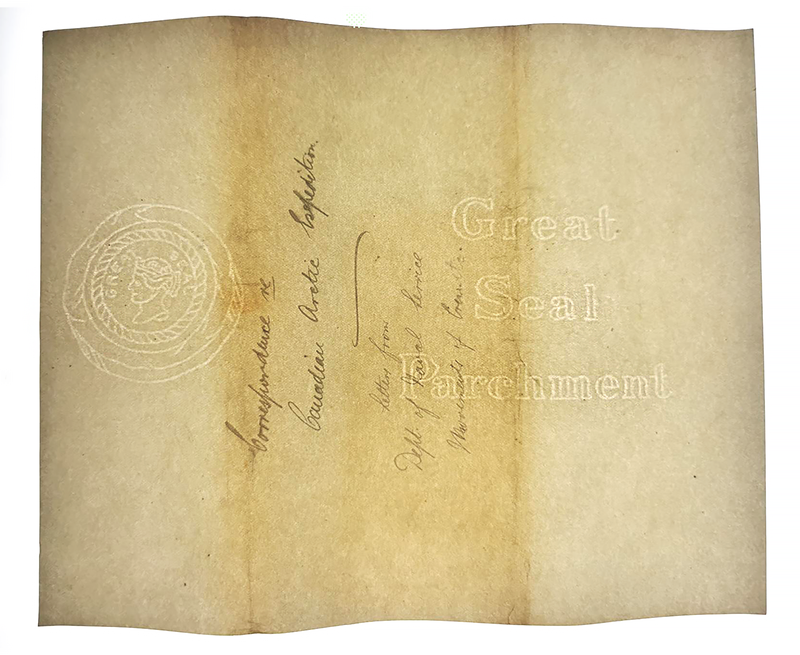

It is also fascinating to see the variety of watermarks that can be found in the paper, best revealed when placed on a light box.

Though simply interesting to look at, they are also useful in telling a story beyond what is written on the paper as they identify the supplier. From there, you can find out where they were based and what years they operated – which can be important particularly if researching the provenance (the origins and past ownership of an object) and authenticity of what the paper has been used for.

Take a look at our previous post for more fascinating information on watermarks.

You can also read more about the papers of William Speirs Bruce here on our online collections resource.

Charlotte Swindell, Digitisation Operator.

Great piece. Very interesting to read and well written. I look forward to more