Musica Getutscht (Basel, 1511) is the earliest printed treatise on musical instruments in the west. Written by Sebastian Virdung who was a priest and a chapel singer, it provides rudimentary instruction on playing the clavichord, lute and recorder. It was also the first of its kind to be written in a vernacular language, making it a widely accessible text. Both Virdung and his printer, Michael Furter, were no doubt aware that this would be an important document to offer the German-speaking world, changing the way music education was delivered and creating a new culture of amateur musicians and performers in the sixteenth century.

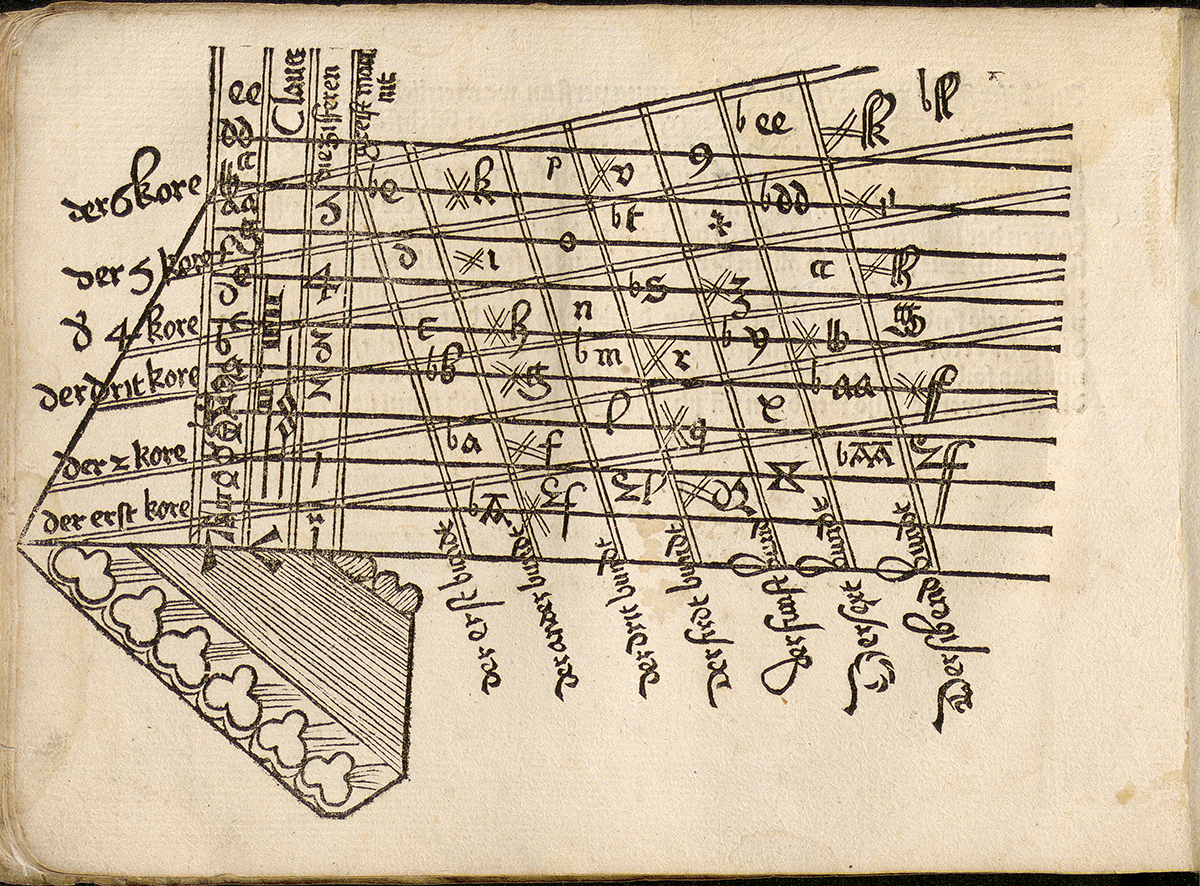

The book is in quarto format, 110 pages including the cover, and has been bound in a vellum manuscript (not the original binding). There has been writing added to the front cover (possibly in the 19th century), “Old German History of Musical Instruments Oblong Parchment”. To decipher the text on the cover I adjusted the colours (slightly radioactive!) in post-processing for ease of readability. Other markings to our text include maths notes, and a child’s scribbles on the first and end pages. It appears that our copy is incomplete, lacking the last few leaves O2, O3, and O4. These missing pages are a continuation of the instruction of recorder fingering that is found in the last section of the book, with a woodcut chart as a visual aid. It’s a shame that the last few pages are lost, but this could have been the reason for the re-binding of the text.

The book is in quarto format, 110 pages including the cover, and has been bound in a vellum manuscript (not the original binding). There has been writing added to the front cover (possibly in the 19th century), “Old German History of Musical Instruments Oblong Parchment”. To decipher the text on the cover I adjusted the colours (slightly radioactive!) in post-processing for ease of readability. Other markings to our text include maths notes, and a child’s scribbles on the first and end pages. It appears that our copy is incomplete, lacking the last few leaves O2, O3, and O4. These missing pages are a continuation of the instruction of recorder fingering that is found in the last section of the book, with a woodcut chart as a visual aid. It’s a shame that the last few pages are lost, but this could have been the reason for the re-binding of the text.

The first page shows a very long title beginning with ‘Treatise on Music in German’ with a following explanation that the text is in the vernacular rather than Latin (the norm for all treatises in the early sixteenth century), and that the work was compiled from a larger treatise. He alludes to the larger work often throughout the book, showing his intentions of publishing a large in-depth study of musical concepts as well as detailed instructions on learning to play certain instruments. There may have been several reasons for doing this – first, it served as a guarantee for potential sales of further books to be published which in turn funded the next round of printing. Secondly, to keep the information brief and to the point so as not to waste the allocated printing space, and lastly, it served as a good introductory book for those keen to learn about music, as it was not deeply technical or serious in its language.

The first page shows a very long title beginning with ‘Treatise on Music in German’ with a following explanation that the text is in the vernacular rather than Latin (the norm for all treatises in the early sixteenth century), and that the work was compiled from a larger treatise. He alludes to the larger work often throughout the book, showing his intentions of publishing a large in-depth study of musical concepts as well as detailed instructions on learning to play certain instruments. There may have been several reasons for doing this – first, it served as a guarantee for potential sales of further books to be published which in turn funded the next round of printing. Secondly, to keep the information brief and to the point so as not to waste the allocated printing space, and lastly, it served as a good introductory book for those keen to learn about music, as it was not deeply technical or serious in its language.

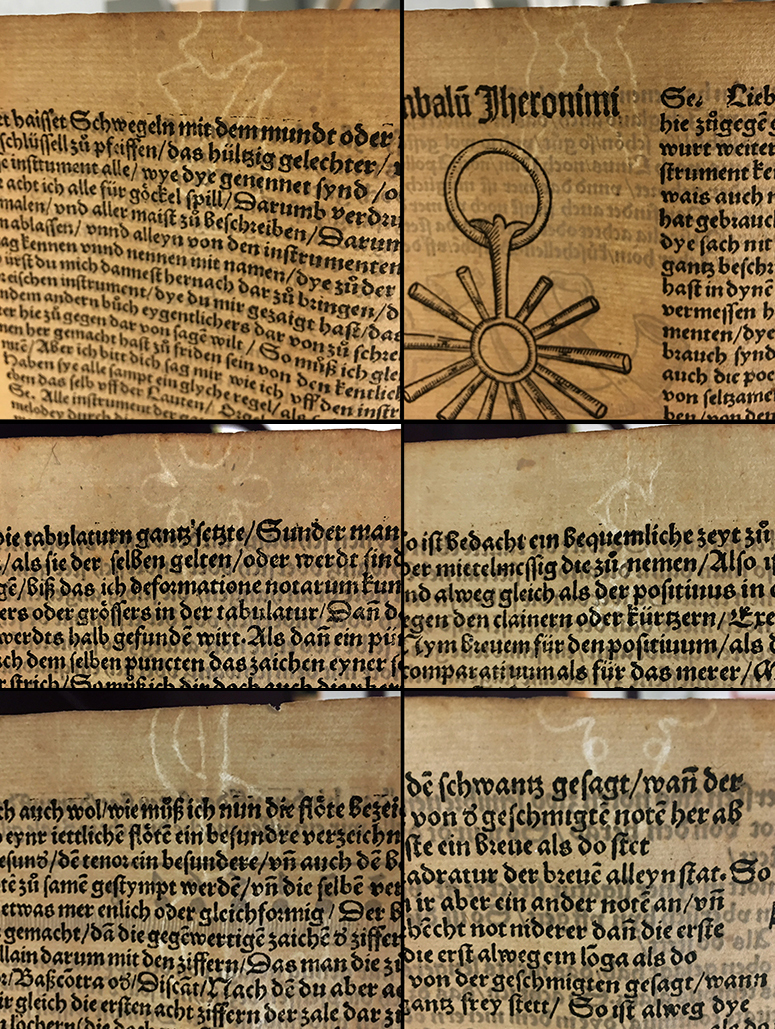

The entire text is written in the guise of an informal conversation with a fictional character, Andreas Silvanus. Their relationship is one of colleagues sharing knowledge rather than master and pupil, and the addition of woodcut illustrations and visual aids to communicate to the readers in an easy and popular style. Interestingly, since the woodblock illustrations have been reversed left-to-right when printing, the names have been typeset incorrectly, appearing above the opposite of the intended figure. In Virdung’s opinion, Andreas Silvanus represented the ideal ‘persona’ to learn a musical instrument, showing him to be a man of the woods (as his name suggests) with a knife in his belt and a boar spear in his hand. It is clear that the academic robed figure is Virdung. He sets the scene with Silvanus, describing what the book will teach him.

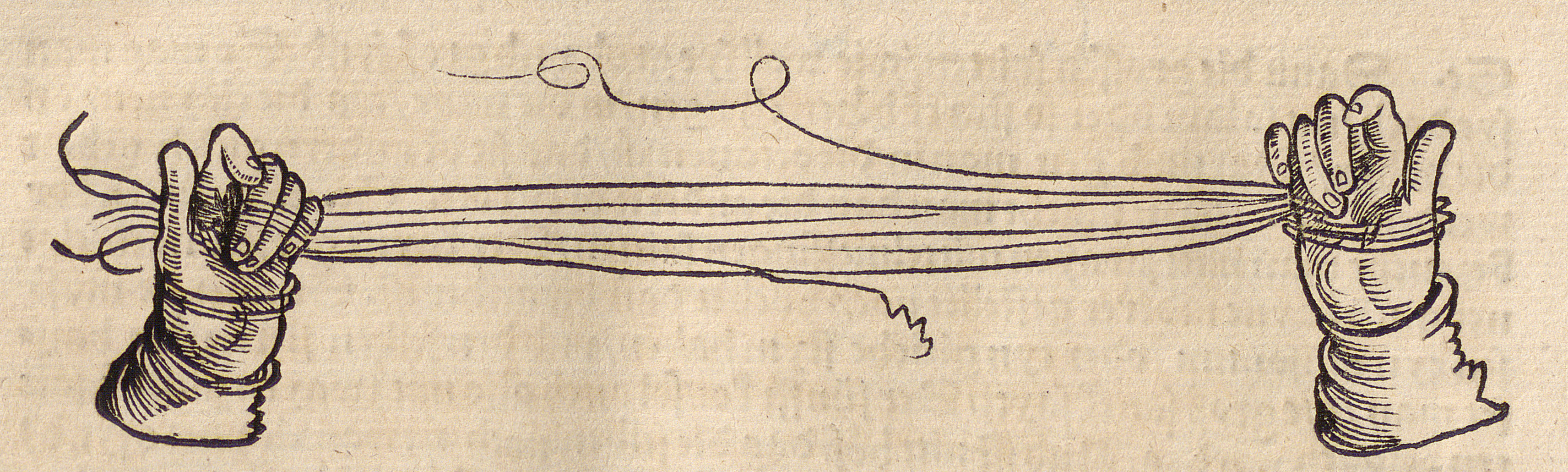

There is an extensive collection of illustrations of musical instruments, which Virdung has separated into three categories; stringed, sounded by air, and ‘metal’ or other resonant instruments. The illustrations are aided by brief explanations by Virdung, who claims that he has returned from travels from which he has brought examples of the instruments he was studying. To him, the major source for his treatise was to be the empirical evidence of the instruments themselves, rather than anecdotal. The do-it-yourself approach gives us insight into music making in that era, but surprisingly, also illuminates other aspects of society in the years just before the Reformation.

In his introductory essay to Musica getutscht, Virdung promotes performance on modern instruments as a Biblically sanctioned avenue toward salvation (“blessedness”) , offering as the rationale for his writing and publishing this little book the idea that its use will increase the number of blessed people. So important is this point that Virdung reiterates it at his conclusion, this placing the entire treatise within the realm of religious duty. Biblical authority, then, is the most prominent element in Virdung’s defence of musical instruments and their actual use by non-specialists. In keeping with his goal of introducing instruments to a public composed of persons from diverse backgrounds and circumstances, he quotes Biblical passages that support his arguments, using the German language rather than Latin. By his use of the vernacular for these as well as liturgical texts, our author foreshadows Lutheran reforms, and he outs himself in the company of other German humanists of his day who places high value on their mother tongue as a proper vehicle for bringing understanding of the literary monuments of antiquity (the Bible included) to a larger segment of society. – Musica Getutscht : A Treatise on Musical Instruments (1511) by Sebastian Virdung / Sebastian Virdung, Edited and translated by Beth Bullard.

One fascinating look into the intellectual climate of the early sixteenth century comes from Virdung’s long phrases explaining the Arabic numerals in his lute and recorder tablatures. He calls each symbol “the numeral that represents the number.” Thus, he carefully separates the graphic symbol from the abstract concept. His unwieldy verbal formula, repeated in every case, reflects the fact that at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Arabic numerals (really Hindu in origin, having been transmitted from India to the West via Arabs) were only just being adopted into practical use in northern Europe. These numerals included the novel concept of zero, which Virdung takes pains to explain as well. – Musica Getutscht : A Treatise on Musical Instruments (1511) by Sebastian Virdung / Sebastian Virdung, Edited and translated by Beth Bullard.

As with many printed books of the time, the varying watermarks and slight differences in woodblock quality show a complicated printing history. With these variations it is also possible to establish printing provenance and date individual pages more accurately.

The fluid nature of the lucrative printing industry brought new waves of woodcut artists who were able to copy existing illustrations for a fraction of the cost. Although delighting Virdung’s contemporaries, they invite criticism today. Indeed, there are questions as to what scale, proportion and perspective the original instruments would have had. The quality and contours of the woodcuts do not give enough detail to accurately portray the instruments in a way that we could make prototype replicas. Thus, the illustrations in Musica Getutscht serve merely as a guide rather than accurately represented instruments.

Musica Getutscht includes a woodcut of a lutenist from the eminent Swiss artist, Urs Graf. Most scholars assumed all the woodcuts were illustrated by him on the basis of a single image that bore his signature. The comparative crudeness of the other illustrations however, clearly indicate that there was no connection with Graf’s work. In fact, the printers haven’t done the best job aligning the title page, using various woodblocks to complete a disjointed border around the text.

Within the first two decades after its publication, Musica Getutscht generated two adaptations into other languages (Musurgia seu praxis musicae and Dit is een seer schoon Boecxken) as well as a subsequent book titled Livre plaisant. The authors of these derivative works selected certain elements from Virdung’s work, but presented them in contexts that differed from the original. Many misinterpretations and misprints created a completely new meaning to certain explanations.

Tragically, Virdung died not long after the first printing of Musica Getutscht, not even being able to oversee addendums or printing errors, thus the larger treatise, his magnum opus that he so often mentions in the text is sadly lost to us. However his legacy continued on throughout the century and well into the seventeenth century, when musicologists like Agripola and Praetorius published their own treatises on music using Virdung’s as a model.

This book serves a great importance as we are able to see through Virdung’s eyes the changes that were starting to occur within Renaissance Germany and the foreshadowing of the Lutheran reformation. Through his use of the vernacular and limiting his focus to musical instruments in German areas, Virdung added to the growing feeling of pan-German national identity of the time.

The entire work can be found on our image repository:

https://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/view/search/what/Musica+Getutscht?q=virdung&os=100

The translation, lengthy introduction, and annotations by Beth Bullard have been invaluable resource, I highly recommend her book for further reading.

https://discovered.ed.ac.uk/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=44UOE_ALMA51152179410002466&context=L&vid=44UOE_VU2&lang=en_US&search_scope=default_scope&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=default_tab&query=any,contains,beth%20bullard&sortby=rank&offset=0

Juliette Lichman

Digitisation Assistant

Be First to Comment