For the last couple of months I have had the pleasure of both volunteering with the DIU and now working a bit more seriously through my work placement as part of the MSc in Book History and Material Culture. My undergraduate degree is in Creative Writing and I primarily focus on Children’s Literature in my current studies, so the Digital Imaging Unit might seem like a strange fit for me at first glance. The exact opposite is true though. In the world of Children’s Literature, illustrations and images in general are essential to the construction and survival of texts. During my time here I have been working on compiling the metadata for our ECA Rare Books Image Collection. This project is dear to my heart for two reasons. 1) I am exposed to images and illustrations of every variety, both artistically and mechanically. 2) I learn something new every day. There are many books in this collection that are far out of my expertise and for that reason I am forced to research all sorts of things I have never even heard of. Because of this I have become a huge fan of nature lithography, Italian architecture and handmade books. The latter is what I would like to discuss today.

As I was researching the ECA Rare Book Collection, I found that many of the materials I was working with had no author and no date. Because of the nature of these type of handmade scrapbook-like works, there is no imprint or page of information on the piece. In this way, dating a work becomes a bit of a guessing game. If there is an attributed author or illustrator one can narrow down the production date to the lifetime of this person. If it is known to be made in a certain region by this person, for example, that can also narrow down the search for the date. It becomes a Sherlock Holmes kind of exploration to put all the pieces together and decide on a more narrow range of dates that a book could have been produced.

In this collection there are many examples of successful dating as well as some cases that have proved to be a bit trickier to pin down. I first noticed this when looking at a page from a hand created book titled by the cataloguer as ‘Album of printed initials, ornaments, illustrations and title pages, cut from books: collected as examples of typographical design, woodcut, engraving, illustration and ornament’. The particular page (see below) is of printed initials that have been cut from another book and then rearranged and adhered to the page as part of a collection of typographical designs, woodcuts, engravings, illustrations and ornaments. The book itself, or rather portfolio because the leaves are not bound together, has not been dated. The reason we know anything about the age of this book is from the age of the books in which were borrowed to create the new one. From some identified works, the collection of images comes from sometime around 1490 all the way to 1715. The pages themselves seem to have been compiled around 1880 to 1920.

A second example of dating from context is a curious photo album from Lord Elgin’s diplomatic missions to China. Unlike with the printed initials, these images have names attributed at points and even dates in the case below. Because of these acknowledgements, it becomes much easier to place this piece in history. Oddly enough though, some photographs are heavily annotated and others sit alone without any clues to what exactly they represent. We cannot be entirely sure when these were taken and if found out to be earlier or later than the other images, it could skew the data on the item as a whole.

A third very interesting undated book is that of calico samples that have been neatly cut and arranged, much like the printed initials from our earlier example. The manufacturers of these fabrics have been identified by the creator, which narrows down the date to the time in which these were all in business. The most helpful bit for this work though is a racehorse. One of the fabrics shows an image of ‘Gladiateur’, a racehorse who was accomplished from 1865-1866. This unsuspecting clue is mighty helpful when trying to confirm the time in which these fabrics would have been made and collected. If this particular horse had gone unnoticed, situated next to many other animal designs, we would know much less about this funny little collection.

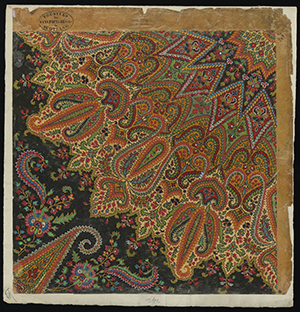

One thing I didn’t expect to gain out of my work placement at the DIU was detective skills but it seems that I now know a bit more about how to date a book than I did a month ago. Unfortunately, there is one book that has no date and also has no catalogue information. This unique piece is a book of shawl designs that have been labelled and neatly placed on paper. There are some clues on these pieces that help us date it to a certain point (most noticeably the stamp from the Trustees for Manufacturers) but even with this it seems to remain quite mysterious. If you feel like testing your skills, feel free to check out the images of ‘Shawl Design’ at http://images.is.ed.ac.uk/luna/servlet/UoEwmm~3~3 and let me know if you find anything.

-Caitlin Holton, MSc Book History and Material Culture

Be First to Comment