While looking through DataShare for datasets about research practice, I found the Hiberlink project dataset [1], which perfectly illustrates some of the challenges the changing digital research landscape poses to good research practice.

The Hiberlink project investigated ‘reference rot’, which happens when a publication includes links that no longer contain the information the authors originally cited. The Hiberlink researchers found one in five articles in their sample contained at least one link which didn’t resolve to the originally referenced content [2].

This project garnered lots of press coverage around 2015-16, and is just as relevant 10 years on, still resurfacing on Twitter every so often. Sometimes the coverage takes a negative bent, from those who view the reproducibility crisis as proof that academia is a waste of tax money and human potential. More often though, it comes from people advocating better, more open research practices.

Richard Tobin, who deposited the Hiberlink dataset, did a good job of completing the metadata and helpfully included a link to the project’s website, hiberlink.org. However, if you follow this link it appears to have expired and been purchased by an unknown party selling “virtual data rooms”. None of us are safe.

Unknown author, “What Is a Virtual Data Room? A Guide to Secure Online Document Management,” Hiberlink (https://hiberlink.org : 5 February 2025); archived at Wayback Machine (https://web.archive.org/) > https://hiberlink.org > 19 March; citing a capture dated 15 March 2025.

Why links die and why it matters

Change is a given in research projects nowadays. The path of enquiry shifts, researchers leave the university and others join, and new tools emerge for carrying out research and sharing findings. Researchers share their work on blogs, project websites, and a seemingly endless chain of social media platforms, moving with the digital tides.

But digital repositories, which are often modelled after physical archives and aim to take a static snapshot of research, can struggle to represent research projects in flux. This article takes a look at how nascent web archives used archiving frameworks taken from the field of librarianship [3].

Traceability is a core tenant of open research, but traceability can be difficult online. Digital and web-based resources often evolve over time, unlike traditionally published articles. URLs in publications or metadata may expire, or the content on the linked page may radically change. Changing content makes the research process less transparent and makes research findings harder to verify and reproduce.

Academic staff are often encouraged to have a strong online presence. Sharing research online is considered an important part of doing ‘open research’, and a strong online presence is seen as important for academics’ personal career development. But most of us don’t often think much about the web of links created during a research project. These links can drift and degrade as researchers leave an institution or move on to new projects, as a pot of funding runs dry, or as reminders to renew a domain registration end up in a spam folder.

The case of web domains is especially interesting, as they can be bought by anyone. Old links to defunct external web pages may lend credibility to questionable groups or dodgy businesses that claim a domain once a researcher’s registration expires.

Why links pose a challenge for data management

While depositing a research dataset in an open access repository seems like a natural conclusion to a project, you might be horrified to learn that the work doesn’t stop here. In data management plans we think about how we can share, store and preserve our data for the future. We don’t usually consider how all the peripheral stuff around our data might also need to be preserved and maintained.

We usually recommend that instead of using a live URL to link to a project website, researchers cite archived copies of the web pages and use persistent identifiers (like DOIs) where possible. The authors of the Hiberlink paper encourage researchers to reference archived versions of the web, like the non-profit Internet Archive. But as could have been the case with the Hiberlink project, linking to an archived copy isn’t ideal if a project website is still being actively updated and you want to direct people to the most recent version.

What can we do?

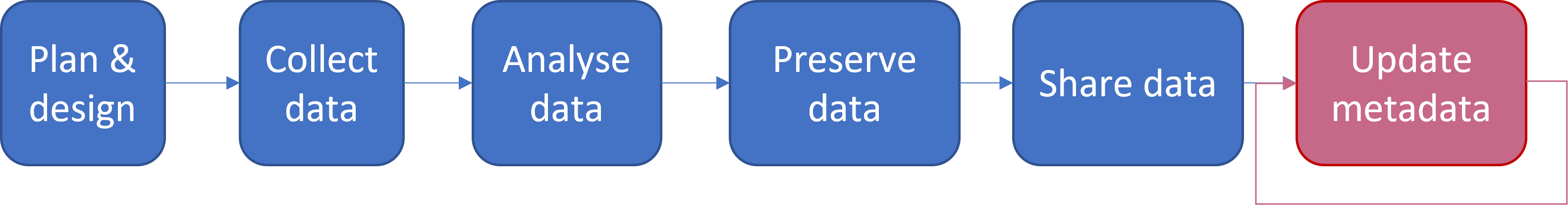

So, beyond using persistent identifiers, how can we make sure that a repository doesn’t contain a bunch of dead links? The obvious answer is that researchers should periodically review all their items in the research repositories at every university they’ve worked at, and update the metadata… forever? As is often the case with good research practice, solutions often require an ongoing investment of time that researchers simply don’t have.

Maybe as data archivists, we have to accept that metadata will decay, and that messy metadata is better than invisible research data.

The metadata update hell loop

How can you avoid reference rot?

For help figuring out how you can preserve your websites, see the university’s resources on web archiving [4]. Dr Alice Austin does regular training sessions on web archiving, which I recently attended and found very useful. And if you’d like advice on linking all your archived research outputs together in a way that ensures they’ll be useful in years to come, get in touch with us!

Learn more about the Hiberlink project

You can read more about these issues in the archived versions of hiberlink.org from before March 2022 in the Internet Archive [5].

If you’d like to read more about reference rot, the authors of this project wrote two great papers on this phenomenon:

Scholarly Context Not Found: One in Five Articles Suffers from Reference Rot [2] looks at reference rot in over 3.5 million STEM articles from 1997-2012 and finds that one in five contains a link which doesn’t resolve to the originally referenced content.

No More 404s: Predicting Referenced Link Rot in Scholarly Articles for Pro-Active Archiving [6] explores the use of machine learning to identify links at risk of rotting.

While writing this blog post I spoke with Richard Tobin, one of the researchers on the Hiberlink project, and he had this to say: “Neither of us is working on related research now, but it would be interesting if someone were to take the data and see how much further the links have decayed.”

Links

[1] Tobin, Richard; Grover, Claire; Zhou, Ke. (2015). Hiberlink project data, 1997-2012 [dataset]. University of Edinburgh. https://doi.org/10.7488/ds/230.

[2] Klein M, Van de Sompel H, Sanderson R, Shankar H, Balakireva L, Zhou K, et al. (2014). Scholarly Context Not Found: One in Five Articles Suffers from Reference Rot. PLoS ONE 9(12): e115253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115253

[3] Hegarty, K. (2022). The invention of the archived web: tracing the influence of library frameworks on web archiving infrastructure. Internet Histories, 6(4), 432–451. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701475.2022.2103988

[4] The university’s web archiving service: https://library.ed.ac.uk/heritage-collections/collections-and-search/archives/digital-archives-and-preservation/web-archiving

[5] Archived version of Hiberlink project website. https://web.archive.org/web/20220306174247/http://hiberlink.org/

[6] Ke Zhou, Claire Grover, Martin Klein, and Richard Tobin. (2015). No More 404s: Predicting Referenced Link Rot in Scholarly Articles for Pro-Active Archiving. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL ’15). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1145/2756406.2756940