Today we have the second instalment of a two-part series by Projects Conservator Mhairi Boyle. Mhairi spent April 2022 working on The Witness, a collection of Edinburgh-based newspapers held by New College Library. You can read the first part of the series here.

The first instalment of this series focused on the contextual background and the condition of The Witness newspapers. In this final instalment, I will be discussing the ethical challenges of digitisation conservation work and reveal some highlight findings from the collection.

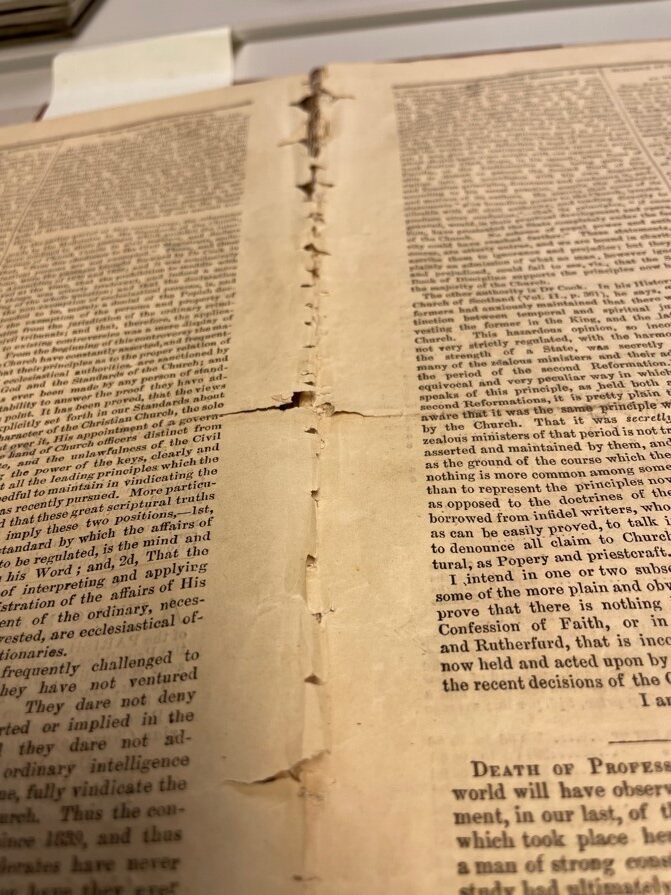

Weak and damaged areas.

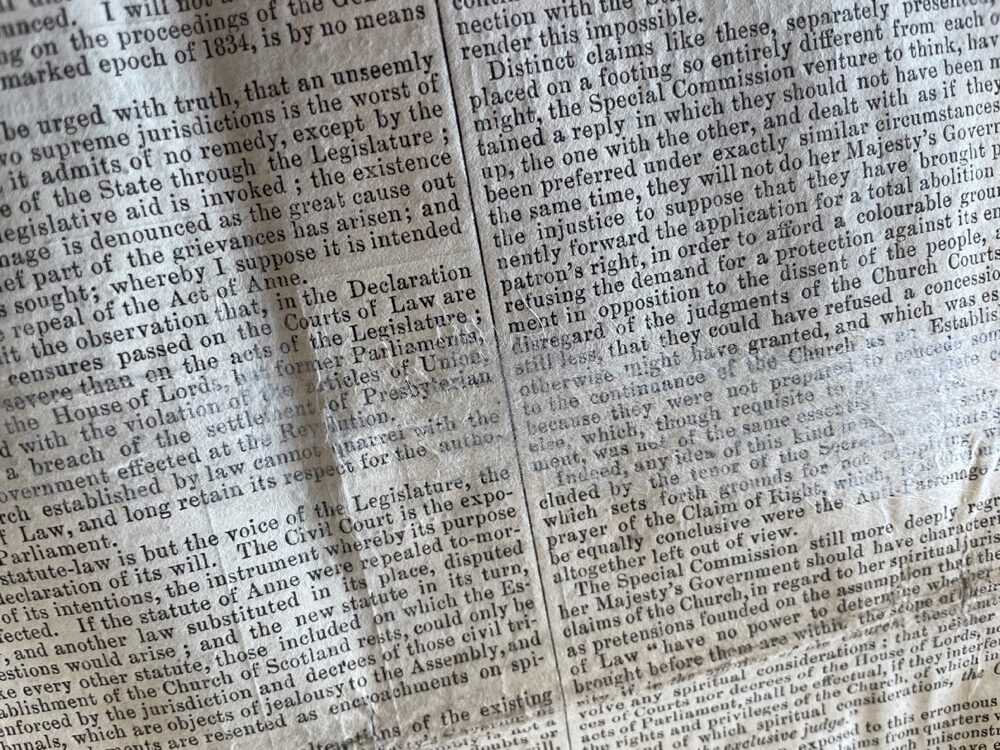

In the Conservation team we often use the terms ‘pre-digitisation treatment’ and ‘post-digitisation treatment’. When assessing objects for digitisation, it is important to consider the condition of each object and how it will be digitised. If the pressing or scanning of an object will worsen its condition, pre-digitisation conservation treatment is often recommended. If there is damage to an object that will not be made worse during the digitisation process, then it can be flagged for post-digitisation treatment. In the case of The Witness, each newspaper will be laid flat, and each page scanned. This could worsen the split areas and areas of weakness when each page is turned for scanning. When each page is pressed, the tension from the old adhesive and thread holding each volume together could also create new splits and damage. This presented a new dilemma: we had to decide whether to keep the newspapers bound, or disbind each volume.

There are pros and cons to each approach. As previously mentioned, the binding of the newspapers was two-fold: there were residual fragments of binding and adhesive from the original larger bound volume, as well as a single thread binding which was added later. Removing the original adhesive would be very time-consuming, and potentially further damage the fragile and damaged edges of each page. After discussing this with the curators and the Senior Collections Manager, we agreed on a partial pre-digitisation disbinding. I removed the additional single-thread binding, which we agreed was adding unnecessary stress and tension to each newspaper. By removing some of the tension from each page, less damage is likely to occur when each volume is pressed flat under a scanner.

The text block was repaired with a thin Japanese tissue, which is strong but also preserves legibility.

I also made the decision to leave the previous repairs in place. Although they have cracked in places, removing them could result in further damage and render` parts of the newspapers illegible. Instead, I repaired vulnerable areas and large losses. I focused on any tears and cracks, which threatened the text block and legibility of each volume. I also repaired areas of weakness which could potentially catch at a wrong angle and worsen when the pages are turned. I used a thin Japanese tissue, which is thinner than the newspapers – this means that if these repairs fail in the future, they should bear the brunt of the damage rather than the original items.

10% w/v carboxyl methylcellulose.

I consulted Projects Conservator Claire Hutchison, who has previously worked on a sizeable newspaper project for the National Library of Scotland, on the best adhesive to use. Claire cited carboxyl methylcellulose (CMC) as her adhesive of choice, because of its viscosity, water content, and drying time. CMC is a ‘cellulose ether’. It is a dry, powdery substance made from purified cellulose commonly derived from wood or cotton. This undergoes a reaction with chloroacetic acid to create CMC, whose structure is more amorphous than pure cellulose. It is commonly used in the food and cosmetic industries as a thickener. In conservation it has three main uses: as an adhesive; to soften and remove historic adhesive; and to strengthen flaky/powdery media. Once it is added to water and vigorously stirred, it magically transforms into a gel overnight.

Because of its gel-like form, it is less likely to further damage fragile paper by way of oversaturating it with water. It dries in a fairly quick time to a clear, flexible film, which is advantageous when working with newspapers, whose pages are turned and flattened.

Areas of weakness have been reinforced with Japanese tissue.

During this project, I became a repair administering machine. Each page of each Journal was re-examined for areas of weakness and repaired.

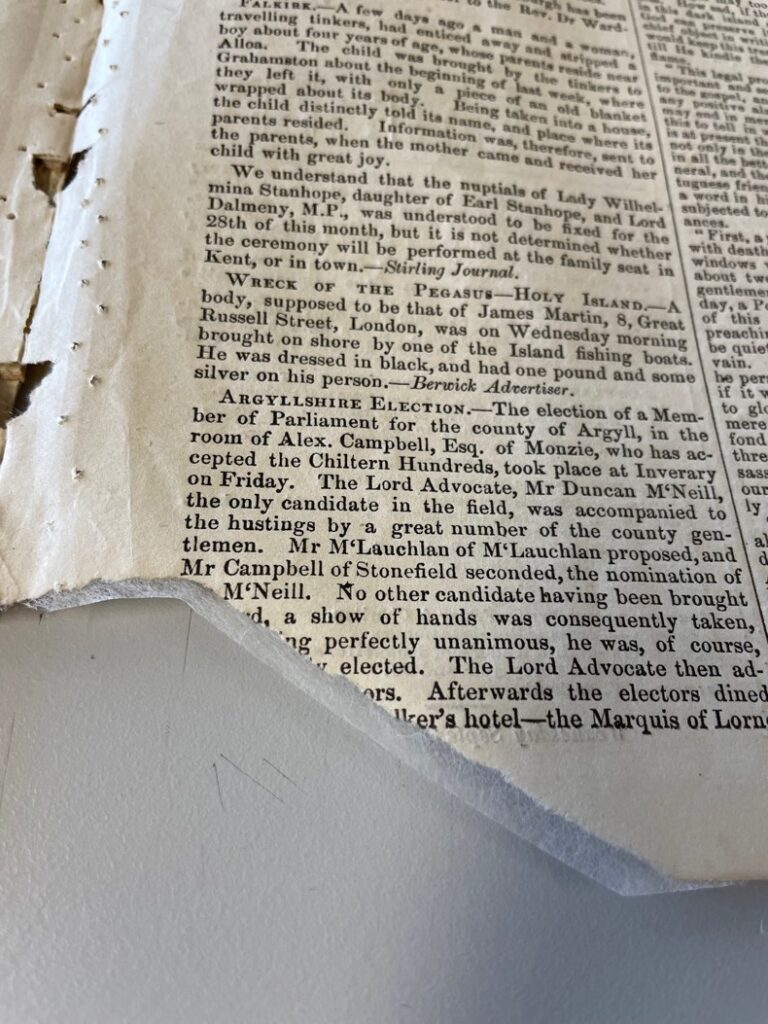

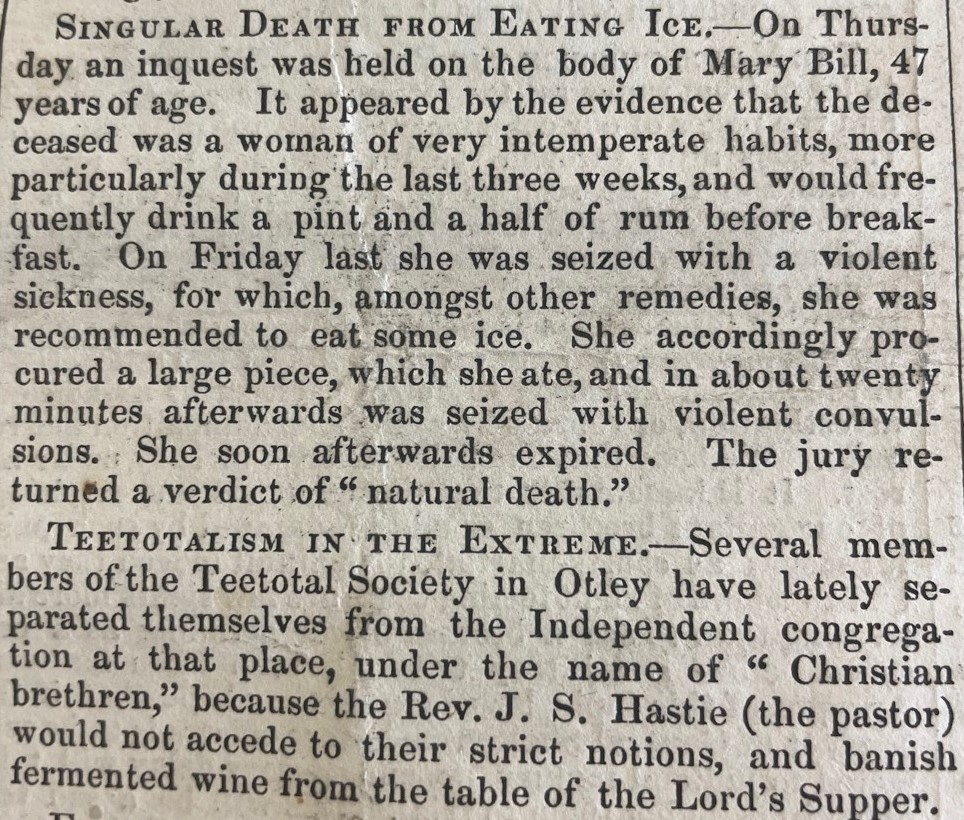

I did stop a few times to check out the local news from 1800. One of the differences between digital news outlets and physical newspapers is that online there is no need for ‘gap-filler’ articles. These happen to be some of my favourite ‘gap-fillers’.

From rum and ice to extreme teetotalism!

It is also interesting to examine the differences between the language used in the 1800 versus today. I think I could take a few tips from The Witness on how to craft concise-yet-sophisticated prose!

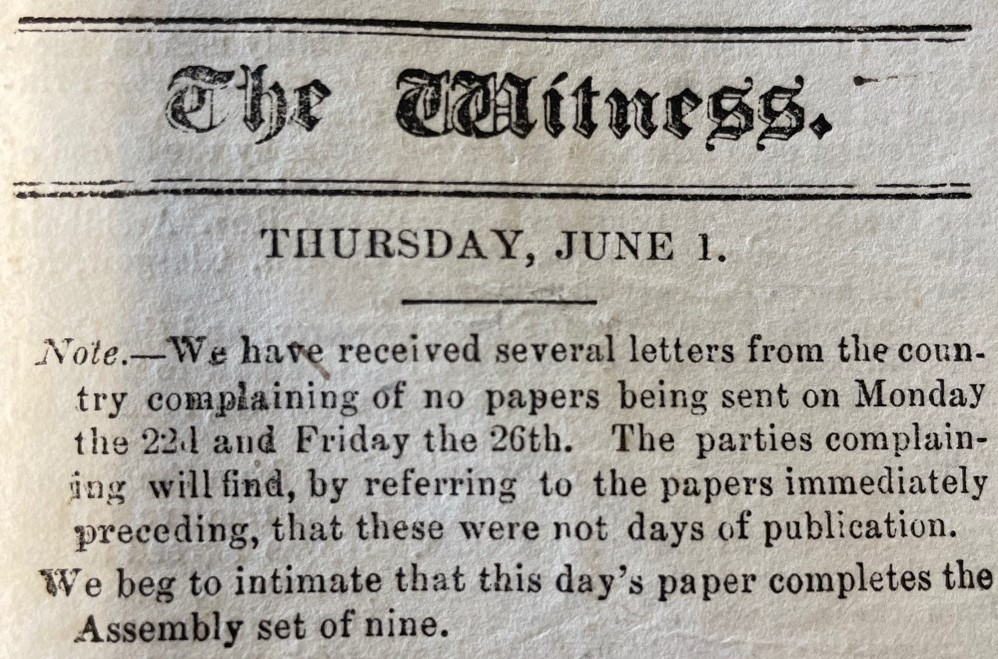

A stern reminder of the newspaper’s publishing days.

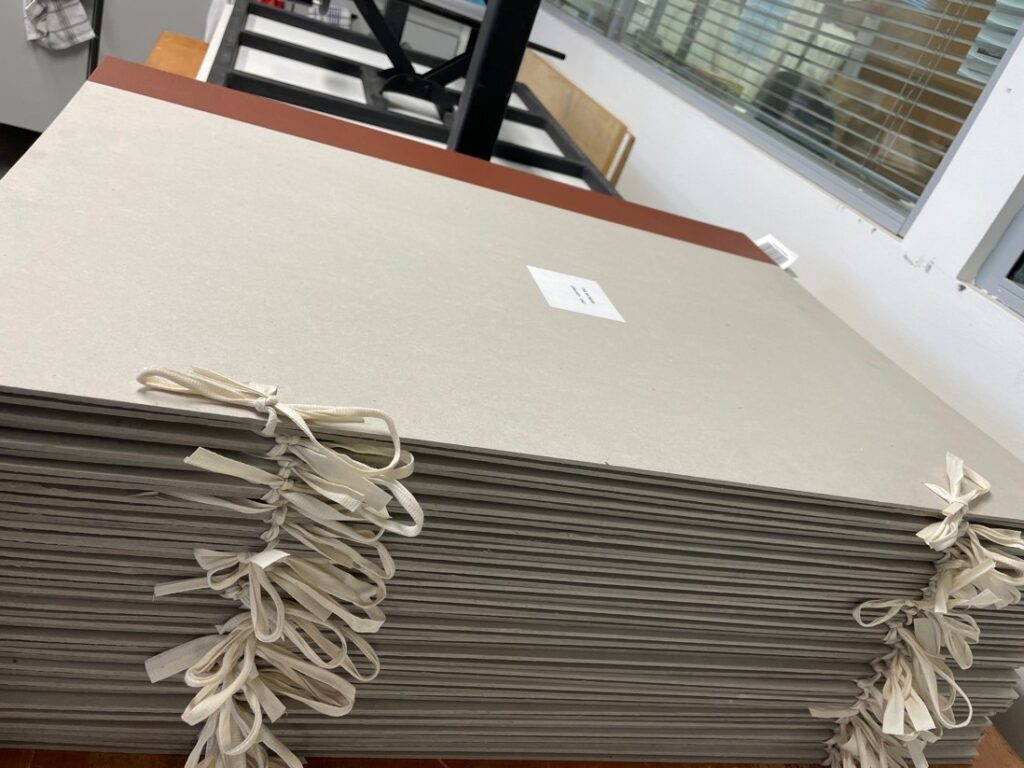

The newspapers are now ready for digitisation.

Now that the pre-digitisation conservation treatment is complete, the newspapers will be digitised and accessible online. However, the work doesn’t stop there. Once they return to the CRC, I will examine them for any further damage and discuss further treatment options with the curators. Options include archival rehousing; testing out removal of the historic repairs; and removing the aged adhesive and historic bindings. Although The Witness will be available online, some users will still prefer to come and interact with the material objects themselves.

One of the reasons I enjoy being a conservator is getting hands-on with collections. With so many workflows now taking place entirely through a computer screen, I find the physicality of remedial treatment work very mindful and refreshing. Working closely with The Witness has reminded me of a slightly slower way of life, when consuming the daily news involved physically engaging with an object rather than scrolling through apps and ads fighting for your attention.

Further reading:

Feller, RL., & Wilt, M. 1990, Evaluation of Cellulose Ethers for Conservation, J. Paul Getty Trust, USA.

Tobey, D.A., ‘Preserving history: Here’s how to keep that historic newspaper for years to come’, NYT Regional Newspapers, https://www.mnhs.org/preserve/conservation/reports/nytimes_preserving.pdf