Today’s blog post concludes Lyell Intern Sarah MacLeans’s two-part series on the Lyell Project. Sarah discusses the variety of work she carried out over the last few weeks of her internship at the CRC.

With my conservation work on Lyell’s correspondence finally being successfully completed in the sixth week of my time at the CRC, I’ve been able to devote the final fortnight fully to – well – to everything else!

My time in this internship has not, of course, been devoted to Lyell’s letters alone. In fact, I have had ample opportunity to pursue work in many other areas of this exciting collection.

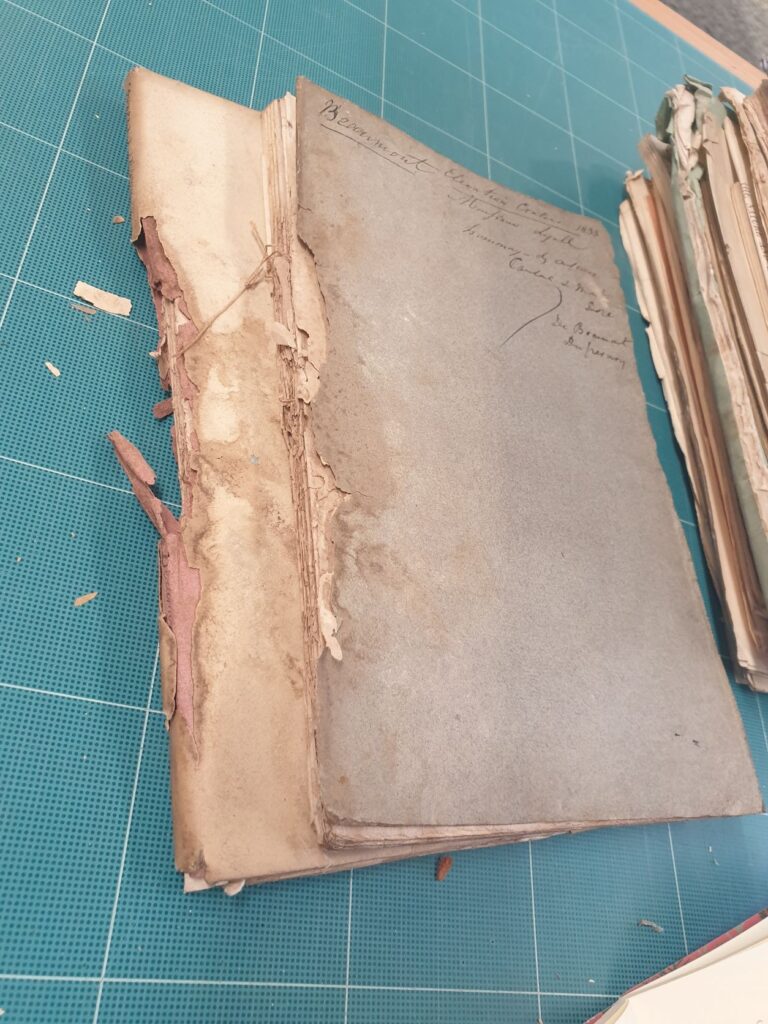

Here I am applying Klucel G in IMS to areas of a notebook cover affected by red rot.

I’ve made the journey out to the King’s Buildings Campus to handle the packing and transport of geological specimens. I’ve made innumerable journeys elsewhere too, gaining insight into the work ongoing at institutes like Historic Environment Scotland as well as the National Library, Museums, and Galleries of Scotland, and forged professional connections with the wonderful staff members there. I’ve boosted my technical skill immeasurably in book conservation, assessing and conserving three of Lyell’s personal notebooks as pictured here. And I’ve rehoused vast quantities of these notebooks by creating book shoes, a bespoke enclosure which protects the notebook but leaves the spine exposed.

After all that excitement, the last big task for me to complete during my time at the CRC has been a comprehensive survey of Lyell’s expansive collection of offprints – a very big task indeed!

An offprint is a separate printing of a work that has originally appeared as part of a larger publication, usually one created by multiple authors – like a magazine, an academic journal, or an edited book. Sir Charles Lyell understandably picked a lot of these up throughout his life, and they range far and wide in subject matter from treatises on the molluscs of Algeria to ruminations on the temperaments of the citizens of 19th Century Reykjavik.

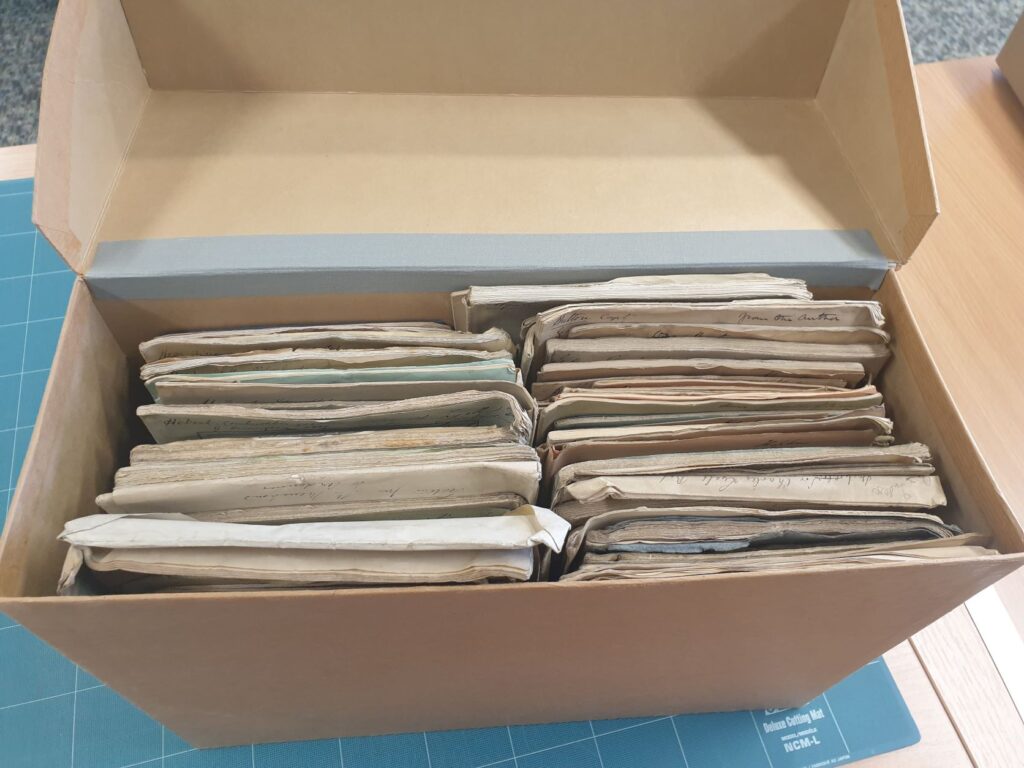

A selection of Lyell’s Offprints in their original state prior to survey and rehousing.

The Offprints also range in physical size from folio (approximate to A4) down to manuscript (more or less A5), a fact that caused initial confusion as the two sizes were alphabetized and housed separately as two different series. And finally, the Offprints range considerably in overall physical condition.

On the whole, they have held up well over the last two hundred years with 12 of the 18 boxes surveyed rating as Grade Two – Fair Condition. The majority of Offprints within this category are reasonably stable, can be handled safely with just a little extra care and attention, and, by and large, show mainly cosmetic or minimal structural damage at worst.

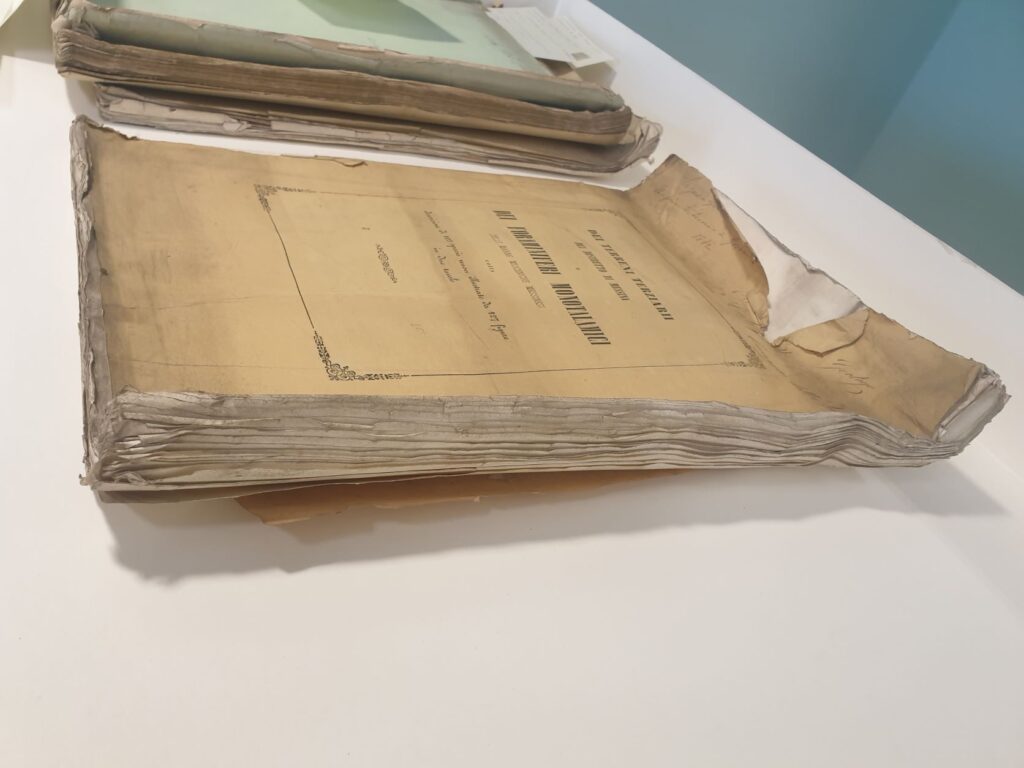

An oversized item that has suffered damage and planar distortion as a result of insufficiently large housing

However, this is not the case across the board.

One issue that I have encountered already in my survey is the issue of size, finding oversized items to be much more common within this series of the collection than initially anticipated. Oversized bound works like that pictured in figure 3 have become distorted and damaged when forced to fit unsuitable housings. Even with time-consuming flattening and other conservation treatment, they will remain too large to fit comfortably within their new housings – so alternatives must be found. As is the case with other oversized flat works like maps and geological diagrams, such items require a great deal of thought and collaboration, leading to a great many conversations with other departments within the CRC to negotiate alternative storage space within available plan chests.

A group of offprints severely affected and embrittled from damage caused by mould.

Another issue that has arisen within this survey is that of the damage caused by mould which, unfortunately, I have discovered within 11 of the 18 boxes surveyed.

I should stress, first and foremost, that the mould I’ve found is historic and entirely inactive. Environmental controls in place within CRC stores have successfully stopped the historic mould in its tracks, depriving it of the warm, humid conditions in which it likes to spread, and ensuring that it can cause no more bother than it already has.

The main challenge that the mould poses now in terms of interventive conservation treatment is the time-consuming surface cleaning process that is now necessary to safely remove it. The mould, although inactive, can appear gritty and is potentially abrasive, so it needs to be removed along with surface dirt in order for the weakened paper substrate underneath to be repaired properly. This, unfortunately, lengthens overall treatment time and potentially complicates the recommendations that I would make about the treatment and care of this part of the Lyell Collection in the future.

Surveying Lyell’s Offprints has been a pleasure not in spite of these unexpected challenges but because of them. The unexpected is something that all archives, libraries and other institutions have to contend with often – as collections grow and become more varied, it can be increasingly difficult just to figure out the extent of what you have, let alone how to handle, and treat it all! The unexpected is also something that I will encounter on a personal level, having now completed my internship and looking to make my next career step as a paper conservator. I’ve gained such invaluable and varied experience throughout my time at the CRC, the challenge of the unexpected is one that I’m now more than ready to meet head on