In this week’s blog, Special Collections Conservator, Emily, discusses how she is using different imaging techniques to reveal concealed script.

I was recently challenged with a seemingly impossible task in the conservation studio; to reveal hidden texts in a book without using any invasive conservation treatment. The item in question is Recueil de Desseins Ridicules (1695), a bound volume with 111 illustrations by French artist George Focus. The illustrations have been pasted down overall on to the pages of the volume, however, there is writing on the verso of the drawings which is now, of course, obscured. Little is known about the artist, and this text is thought to be unique, so being able to read it could reveal a great deal about this enigmatic figure.

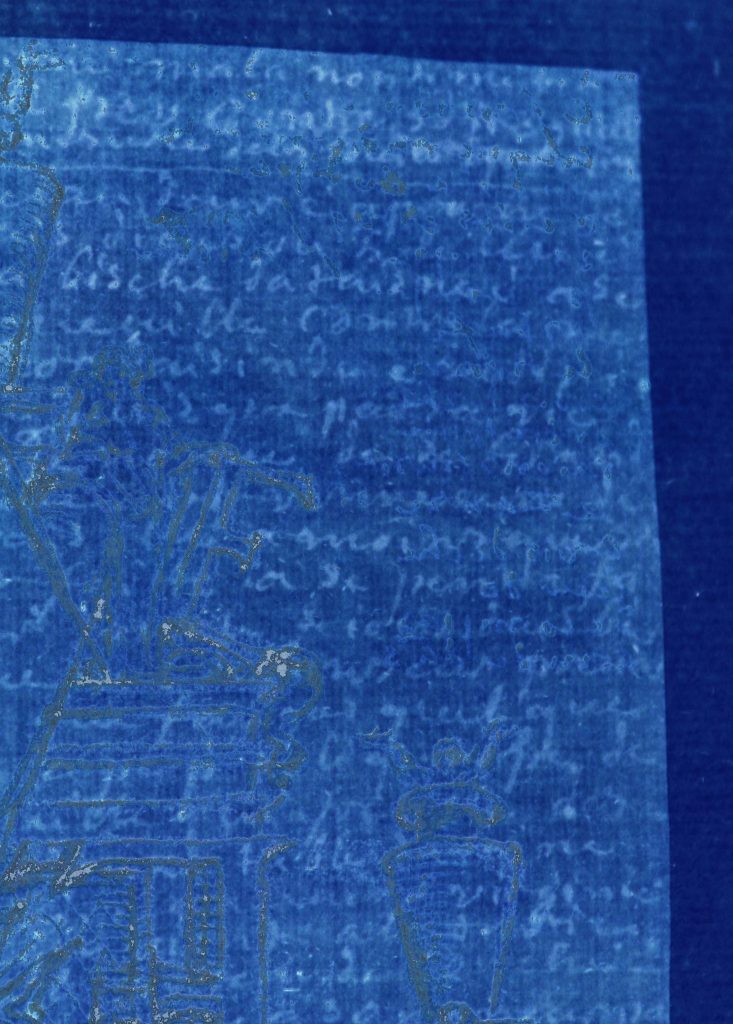

Illustration from Recueil de Desseins Ridicules (1695) by George Focus

One way to view the writing is to remove the illustrations from the page using an aqueous method to soften the adhesive and peel the item away from the page. However, this is highly invasive and there are multiple risks involved. Media could bleed or be washed away completely. Also, when paper becomes wet, it become very fragile, so there is a high risk of loss or damage to the sheet during treatment. Prior to carrying out this type of treatment, each ink used would have to be tested for solubility, making this a very time consuming and labour intensive task. As such, this option was quickly discounted, as we felt that other, non-invasive treatment options would have to be exhausted before attempting treatment of this kind.

Due to this, I began to research different imaging techniques that could be used to reveal the concealed script. One option that has been used successfully to capture images of previously unseen handwriting is Macro X-ray Spectrometry (MA-XRF). This method uses a thin beam of X-rays to scan the object, charting the presence and abundance of various elements below the surface to create digital image. Have a look at this article for more information on this topic.

Image courtesy of Leiden University Library. 180 E 18: large fragment inside parchment binding – Photo Anna Käyhkö

Although this technique would be ideal, it is not offered commercially in the UK, and can be very time consuming to carry out; up to 24 hours per page. This would be our preferred option, and it may be possible in the future to have a research collaboration with an institution who has this type of technology available.

With the first two options not immediately viable, we decided to experiment using transmitted light (light shone from behind the item to the front) and Photoshop. Transmitted light showed up the writing on the back better than in normal lighting conditions, but it still wasn’t clear enough to be read easily. To solve this, we flipped the image in Photoshop, so that the writing on the verso was the right way round. We then attempted to reduce the image layer on the recto by adjusting the RGB channels, and the brightness and contrast. We then inverted the colours in attempt to make the writing stand out. Although this was relatively successful and some words could be read, it wasn’t enough to get a clear picture of the whole of the page, especially in areas where the sketching was dense. However, I do think this technique has some scope in the future for revealing small lines of hidden text.

Detail, photographed in transmitted light

Detail, photographed in transmitted light, and adjusted in Photoshop

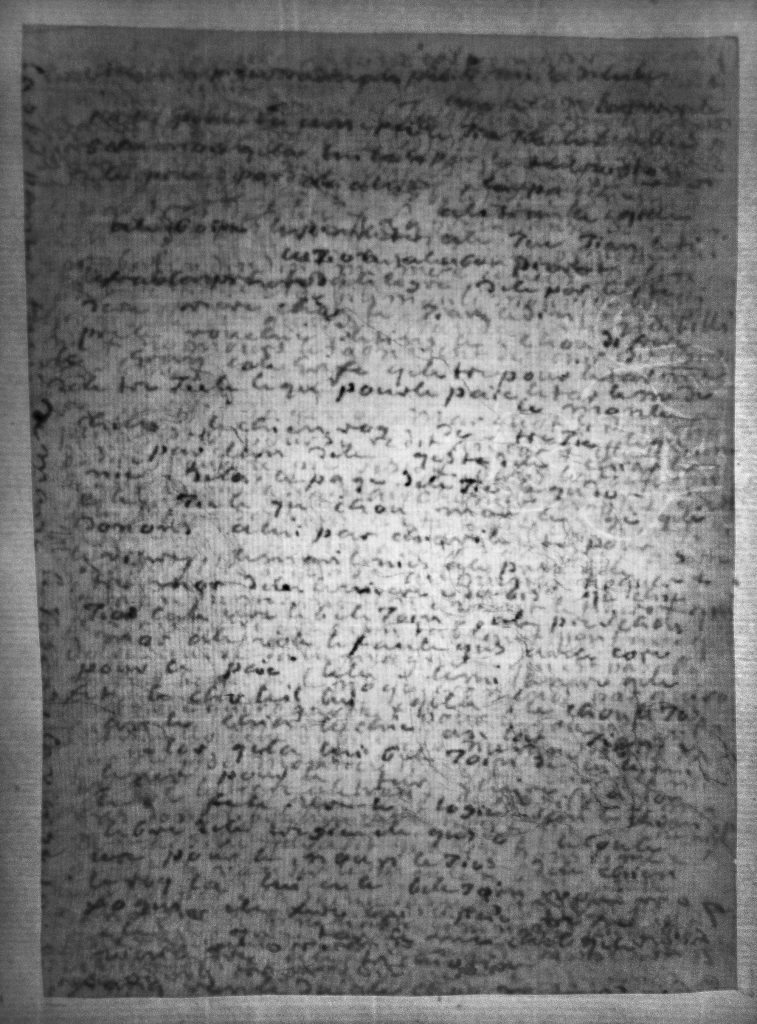

Lastly, we photographed the verso of the page in transmitted infra-red (IR) light. IR light has been frequently used reveal preliminary sketches, underdrawings, or compositional changes that lie beneath visible paint layers. We were able to carry out test shots in our digital imaging unit and the results were surprisingly effective. The writing on the verso was much clearer.

Whole recto photographed in reflected light

Whole recto photographed in transmitted IR light

However, the equipment available at the CRC is not ideal for this type of imaging technique, so the image is still not crystal clear. We hope to partner with Historic Environment Scotland (HES) to use their Multi-Spectra Image System (MUSIS) to carry out further examination of these illustrations. Watch this space for the results of this experiment!

Emily Hick

Special Collections Conservator