This is a guest blog, written by one of our History of Art interns, Rose Hussey.

As part of my Master’s degree at the University of Edinburgh, I have undertaken an internship at the Centre for Research Collections. Throughout this term we have been preparing for the India Exhibition for summer 2017. My part in this involves cataloguing and researching nineteenth century photographic albums, filling in the gaps in the CRC’s database. During this process I have made an interesting discovery, in relation to one particular album.

Linnaeus Tripe (1822-1902) toured South India in the late 1850s as a government employee and photographed art and architecture that he considered to be under risk of falling into ruins. The University of Edinburgh has a good collection of these albums, with views of landscape and architecture from across India. Some of the best of these images are found in his album The Elliot Marbles, published 1858, which capture the contemporary Madras Museum’s collection of the ‘Amaravati Marbles’ (now mostly in the British Museum) from Amarāvatī Mahācaitya (or ‘great sanctuary’) in the Guntur district of India.

In fact, the University is in the rather the unique position of holding two copies of this album. These copies, one from the original University collection, the other incorporated in the collection after the 2011 merge with Edinburgh College of Art, were presumed to be identical. On a cataloguing mission, I have been going looking at these albums, and many others by Tripe, finding out as much as possible about each. Starting with the CRC’s original copy, I went through The Elliot Marbles, trying to identify the sculpture(s) in each photograph, comparing them to the actual objects now in the British museum, and putting together the narratives for every image. Particularly useful was the British Library, who have put a list of the images in their copy of the album online. Our copy seemed to match theirs precisely, so it was slightly surprising to discover that this was not the case when compared to the ECA copy!

Although these volumes only differ slightly, any disparity gives an insight into photographic practices in the nineteenth century, while also raising questions. While a single copy gives a great platform for understanding the album as an art object and an insight into documentations practices and priorities during the British Raj, two copies gives an incredibly unusual potential for comparison between editions.

Below are a few examples of how exactly these copies differed, and an indication of why this might be interesting to us.

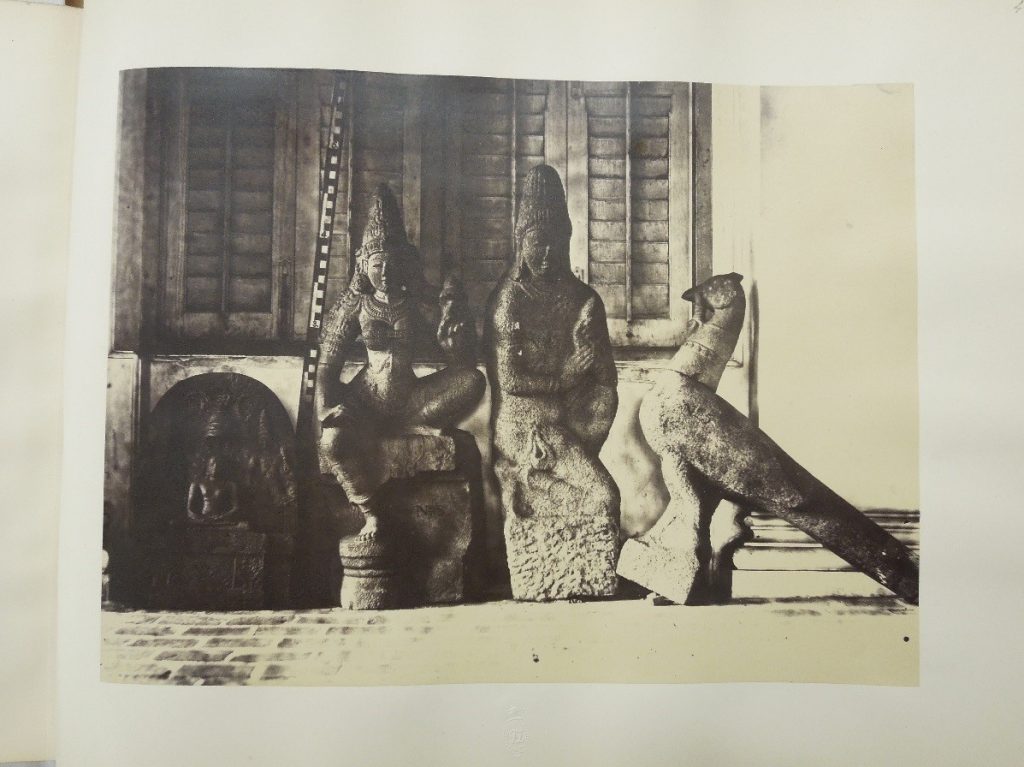

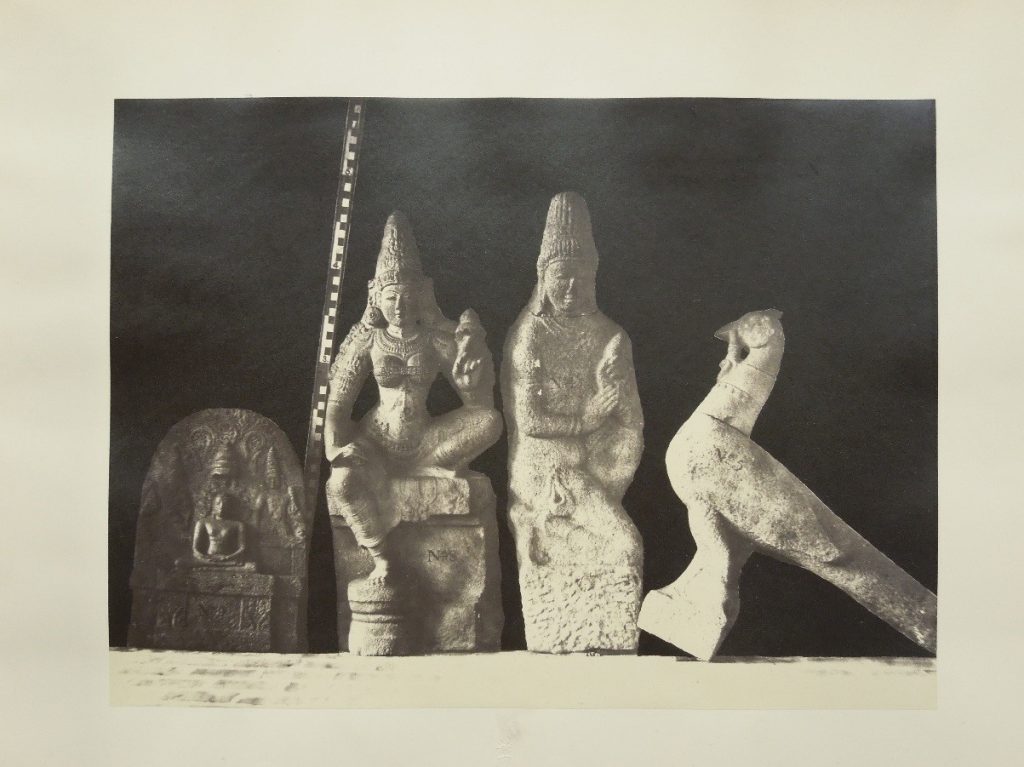

One of the most common differences between these albums are different blacked out backgrounds. So far we cannot discover why these changes occurred. These photographs are all albumen prints, a technique that was popular in the mid-nineteenth century because of its glossy finish and susceptibility to nuanced light. Blacked-out backgrounds were a common way to make the object itself stand out on the page – particularly important for Tripe in his documentation of these marble fragments. This would have been done by painting over the negative.

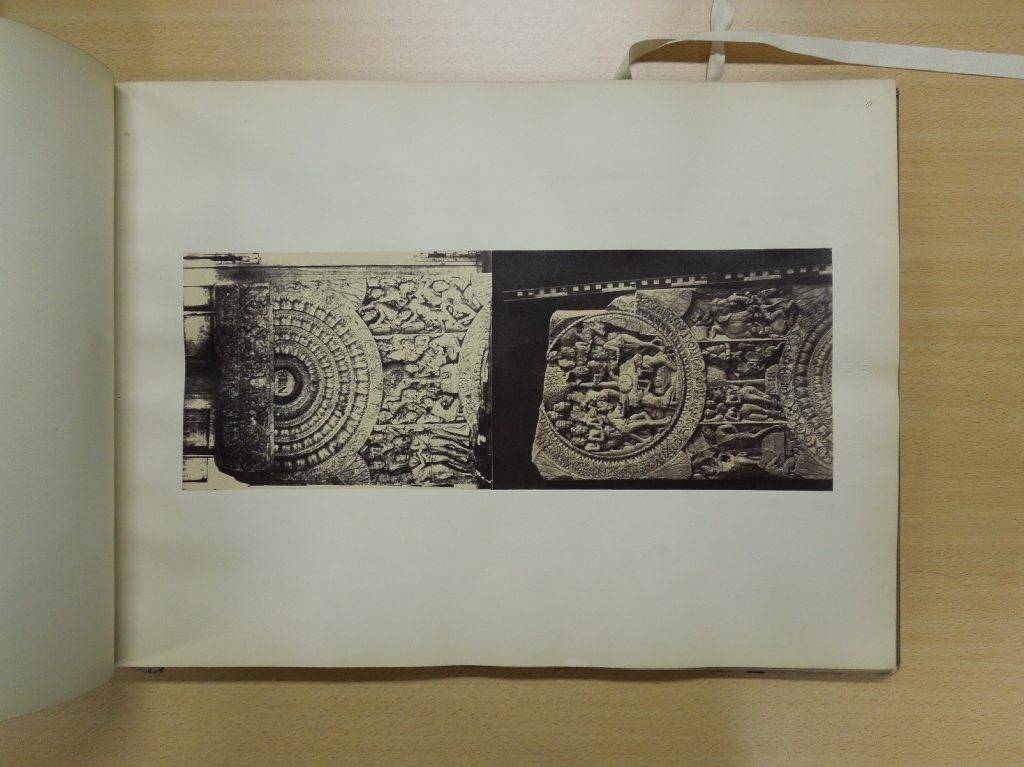

Linnaeus Tripe, Miscellaneous sculptural pieces in The Elliot Marbles, 1858 (CRC copy)

Linnaeus Tripe, Miscellaneous sculptural pieces in The Elliot Marbles, 1858 (ECA copy)

These differences shows how much contemporary photographers edited their negatives, which is interesting because at the time photography enjoyed the reputation of being relentlessly truthful- it was predominantly used as a factual or un-biased recording resource.

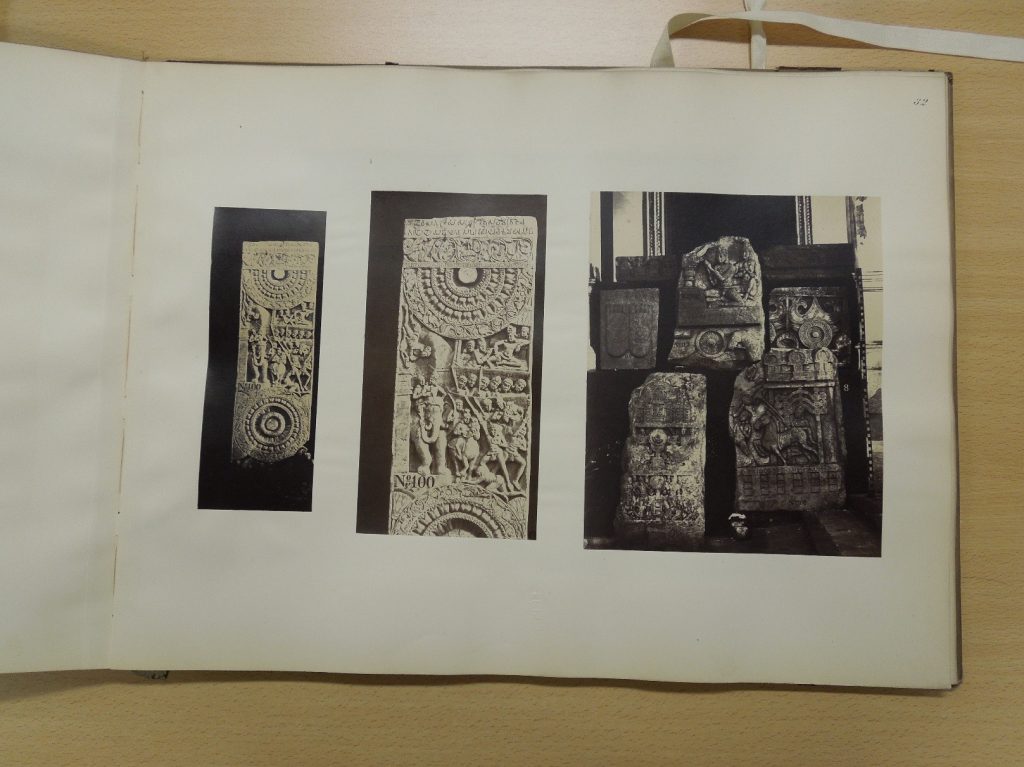

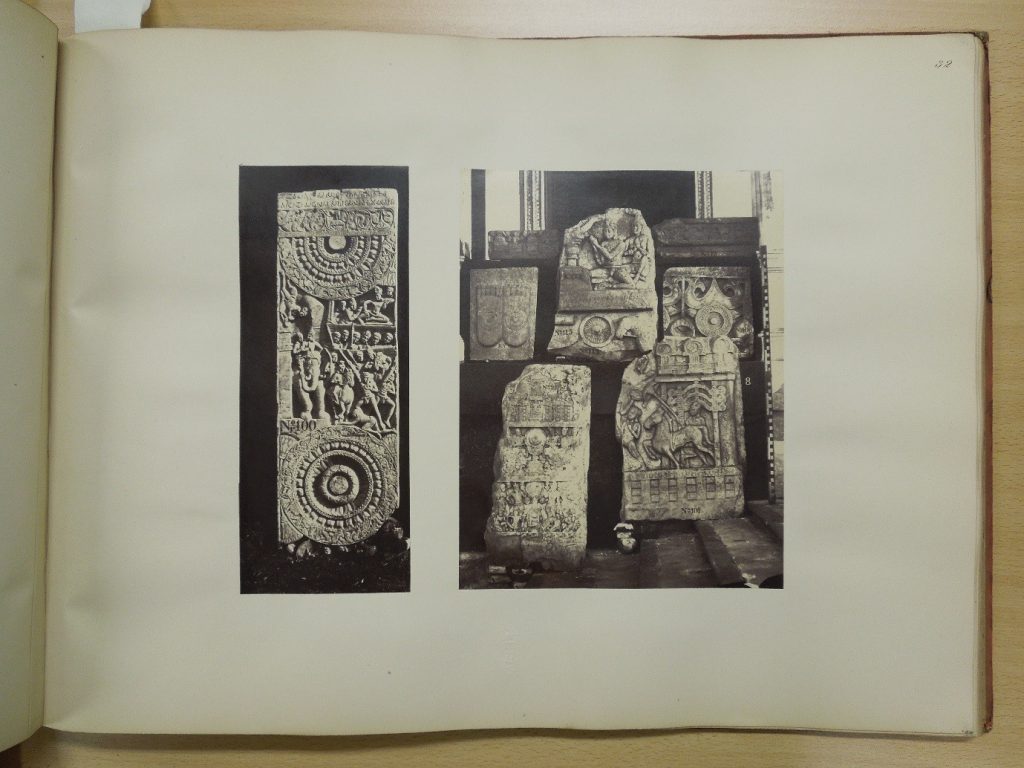

Other differences included an extra image and a removed image in each album, including/excluding detailed views. With the added image, it could be from an original negative that just wasn’t’ included in the CRC copy, or it could be a zoomed in print of a pre-existing negative.

Linnaeus Tripe, Railing crossbar (inner face), Railing crossbar (inner face detail) and Miscellaneous sculptural pieces, in Elliot Marbles, 1858 (ECA copy)

Linneaus Tripe, Railing crossbar (inner face) and Miscellaneous sculptural pieces, in Elliot Marbles, 1858 (CRC copy)

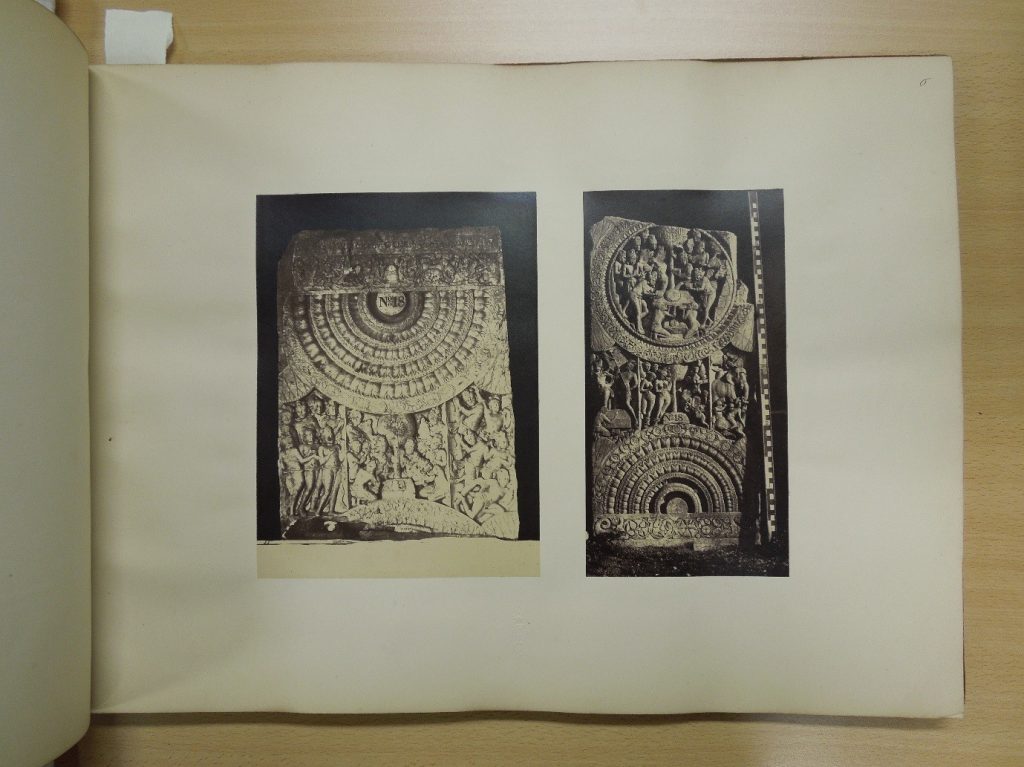

Then there are also formatting differences, which reinforce that each page was done by hand, the photograph stuck in with adhesive and then individual folios placed together and bound.

Linneaus Tripe, Inner face of railing pillar (upper portion) and Inner face of railing pillar (lower portion), in The Elliot Marbles, 1858 (ECA copy)

Linneaus Tripe, Inner face of railing pillar (upper portion) and Inner face of railing pillar (lower portion), in The Elliot Marbles, 1858 (CRC copy)

Furthermore, the measurements of each photograph were different in both albums, reinforcing the fact the each photograph would have been individually printed from the negative and then hand cut. Such differences, while individually small, reveal the individuality of these albums. An opportunity such as this, side-by-side comparison, is very rare and has yielded some interesting outcomes.