By Dr Teàrlach Wilson

The first time I ever visited the SSSA, I was being given a tour by my supervisor to-be. I hadn’t officially submitted an application to do a PhD at the University of Edinburgh yet, but I had come up to Edinburgh from London to meet with my supervisor to-be, Dr Will Lamb, and to have an introductory tour of the University and the resources I hoped to work with. The SSSA was one of the reasons that attracted to me to Edinburgh. It was especially the moment that Will was showing me the Linguistic Survey of Scotland materials (collected between 1951 and 1963), and my eye was caught by a folder on which was written ‘St Kilda’. Anybody with an interest in Scottish history, culture, and identity will be fascinated by St Kilda, and there is often a nostalgia for what once was. As a linguist with a particular interest in geographical variation (‘dialects’), I was immediately excited and saddened by a very simple fact represented by the words ‘St Kilda’ on a document containing linguistic material: when a community ceases to exist, its special variety of speech also ceases to exist. The loss of the St Kilda dialect is not just a loss of localised language and cultural knowledge, it is also a reduction of the Scottish Gaelic language more generally. We have to be eternally grateful to the organisers and fieldworkers of the Linguistic Survey, or else this dialect – and others – could have been lost forever. We may never regain these dialects, but at least we have some idea of the linguistic patterns that existed within them. A great frustration for those studying linguistic variation is the lack of data available from previous periods of history, and it would be a great shame to have failed to collect this data in the 20th century when recording methods and technologies were available.

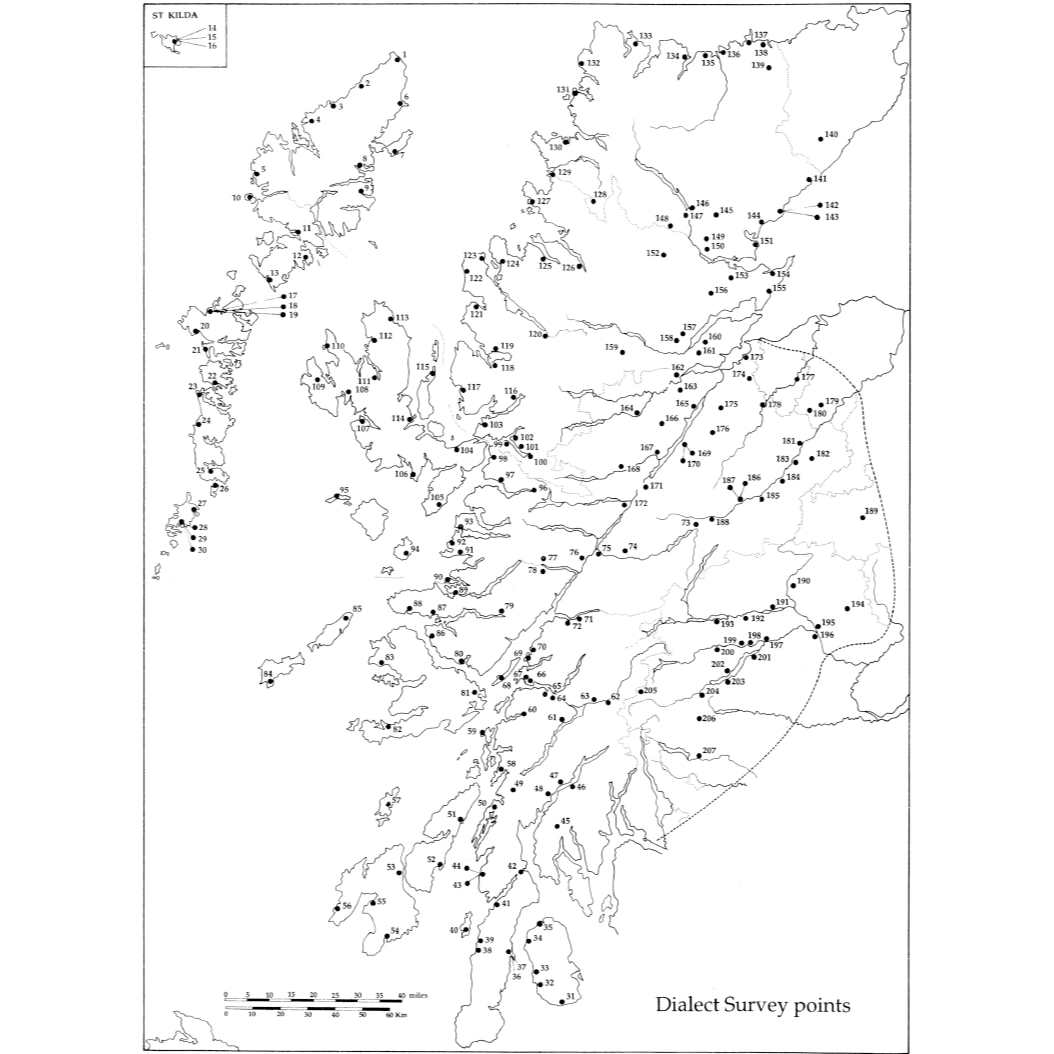

St Kilda isn’t, of course, the only ‘lost’ dialect to have been captured for posterity in the Linguistic Survey of Scotland. Another painful fact for those interested in Gaelic – be they linguists or from other disciplines – academic or not – is the generally northwesterly withdrawal of Gaelic across Scotland, so that the majority of mainland dialects are now obsolete and the Outer Hebrides are the last stronghold of the language. If you open the Linguistic Survey materials, or the only publication to come of the Linguistic Survey – ‘The Gaelic Dialects of Scotland’ (Ó Dochartaigh (ed.) 1997) – you will find this map of Scotland that represents the location of speakers who contributed their speech to the archive material:

Look at the geographic extent of the fieldwork activity! From as far north as Srathaidh (Strathy) in Sutherland to Sean-achaidh (Shannochie) at the most southerly tip of the Isle of Arran – and from as far west as Hiort (St Kilda) to Bràigh Mhàrr (Braemar) in Aberdeenshire – the entire Gàidheatachd (‘Gaelic-speaking region’) seems to be represented (except Loch Lomond, the Cowal peninsula, the Isle of Bute, and the south end of the Kintyre peninsula). By looking at this map and not looking at census data, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Gaelic was in a strong position – having so many speakers across the Scottish territory. However, the Linguistic Survey fieldworkers were also quite thorough in their note-taking and hints at the impending shift can be found in the notes that they took. On a number of occasions, fieldworkers talk about struggling to find speakers or note that the speakers have few, if any, fellow Gaelic speakers within their local social networks. Take into consideration that the majority of the contributors to the Survey were elderly (most being born in the 1880s), and you realise that the fieldworkers arrived at the cusp of a tipping point where traditional local Gaelic dialects go from ‘just holding on’ to ‘no longer existing’. Some fieldworkers even suggest that ‘linguistic decay’ (a term I absolutely loathe) is observable in the speech of those Gaelic speakers who represent the last speakers of their areas and who have perhaps not spoken Gaelic for years, even decades. The implication of this is that some of the material in the Survey don’t not, in fact, represent the traditional local dialects of some areas (Another term used is ‘linguistic attrition’, but I describe it as ‘contact-influenced change’ in my work to show that linguistic changes are natural and that ‘contact’ with the dominant language – English in our case – are driving some of those changes).

When I commenced my fieldwork – with the intention of comparing dialects of the Linguistic Survey with the dialects of speakers of a similarly elderly age today (who represent the grandchildren – or at least the grandchildren generation – of the contributors to the Survey), I found that the geographical extent of my fieldwork was going to be far more restricted than the range had by the fieldworkers who collected the Survey data around 60 to 70 years ago. Imagine the excitement of seeing historical linguistic forms mixed with an overwhelming sadness that they are lost. The emotions were, and still are, sometimes debilitating. I’d be looking at materials in the SSSA, with people around me in silence also looking at materials, and the rollercoaster of emotions would go from wanting to scream, “WOW!” to wanting to cry. I’m sure I wasn’t alone. There is sometimes a melancholy in the SSSA (which should never put you off going there) because visitors and researchers are all feeling the pain of loss – a loss that was so unnecessary. Sometimes you did not speak to fellow visitors or researchers, and so you had no idea what they were looking at or that they were feeling loss. Yet you still sometimes knew. As though a united purpose of capturing loss and criticising the unnecessary causes of loss was reverberating around the building. As I said: don’t let the melancholy put you off – it is a form of human bonding and communication. And that silent bonding is sometimes the most powerful.

It should go without saying that it’s not always melancholy. As I said, there are some moments of almost extreme excitement. One of the things that I enjoyed most about my research was finding contributors to my fieldwork who remembered or were related to contributors to the Linguistic Survey in the 1950s and 1960s. Reading fieldworkers’ notes about people – probably based on short experiences with the people and making assumptions sometimes driven by the fieldworkers’ own assumptions – and hearing stories about the same people from their neighbours and descendants made my cheeks hurt from smiling so much. Seeing a name written in the Survey and then asking a contributor, “did you know X?”, which then led to information not recorded in the Survey was like finding a precious treasure trove – the dialectological equivalent of finding Tutankhamun’s tomb. The similarities or differences between the accounts of people’s personalities and type of Gaelic was always amusing. I remember in particular one fieldworker noting how a female contributor had been quite conservative – almost archaic – in her use of Gaelic grammar, and then a neighbour of this woman (who must have died some half a century ago) recounting how forced her Gaelic sometimes seemed, how pious she was, and how miserable she was! She’d apparently often come to the door as she saw people passing her bothy on her croft just to lament at the state of the world! Something not noted in the fieldworker’s accounts, but you could certainly sense that it was the same woman! Maybe the fieldworker hadn’t been around long enough to witness her lamentations, or maybe she was on her best behaviour with the fieldworker, or the fieldworker wasn’t a member of her close social network. Nonetheless, the fieldworker’s comments about her Gaelic being old-fashioned made me think as I heard stories about her, “yes, it makes sense that someone like that would have some very old-fashioned speech!”

My fieldwork ended up being restricted to the Hebrides – both Inner and Outer. I went to the most northerly inhabited point of the Hebrides (Nis, Leòdhas, or Ness, Lewis in English) and to one of the most southerly (Port na h-Abhainne, Ìle, or Portnahaven, Islay). It was not easy to find contributors and my fieldwork is not as exhaustive as the Linguistic Survey. But combining Archive research with fieldwork in rural island communities has certainly been one of the most enriching experiences of my life, that has really informed who I am today and helped me develop my views and feelings about rural island communities, minority languages, and the importance of cultural – tangible and intangible – in a post-colonial, urban-centric, and land-facing society. I didn’t look at these people’s contributions to Lowland life, but make no mistake about it: rural island communities know how to survive when most Lowland urbanites only know how to go to a supermarket. Island communities are at the forefront of action against climate change because they know how to work their land sustainably while they will be the first to see the consequences of the climate crisis, as big cities invest in infrastructure to protect themselves from rising sea levels. All the while, the members of these communities are the guardians of our cultural and agricultural heritage, who provide us with food and energy. It’s not just their speech that needs to be protected. Their speech is just one facet of their entire way of life that needs to be protected. You may not see that when you look in the St Kilda folder and see that the typical Hebridean pronunciation of bàta ‘boat’ (sounds a bit like paaaaahhhhtuh) was not a feature of St Kilda dialect, even though St Kilda is a considered a Hebridean island (they said something more like baaaatuh). But all these issues are interlinked and the voices calling for respect and understanding of our world ring out through the records of their speech. This is worth thinking about while COP26 is going on in Scotland’s biggest city, i.e. how linguistic minorities protect the planet and what those (mainly male) world leaders need to do to protect them. Linguistic diversity is a part of our planet’s biodiversity, and so the loss of a dialect is like the extinction of a species and the SSSA like the Natural History Museum in those terms.

Dr Teàrlach Wilson is a former University of Edinburgh student, who completed his PhD in Celtic and Scottish Studies in 2021, looking at the links between Gaelic grammar, dialects, and geography. He now lectures Scottish Gaelic at Queen’s University Belfast and is the founding director of An Taigh Cèilidh, a nonprofit Gaelic community hub in Stornoway, Outer Hebrides.

Very happy to have read this. I am glad you included your points about emotions during research. Far too much fieldwork is deprived, “sanitized” before publication and we miss the humanity behind a language, which supports a language’s survival. Great point about COP26 and leaders being mostly male. I may be completely wrong, but is it not that in some distant past women used to be the ones with knowledge and applied it to medicine, storytelling, education? Meantime most men were occupied with stealing cattle and killing. Thus came the “owners” of land, or as they ended up being called, the Nobles, who then created the lawyers to protect private property – a totally unnatural concept, in my mind. I was glad to visit Park recently, just to find out it has been bought out by the community.