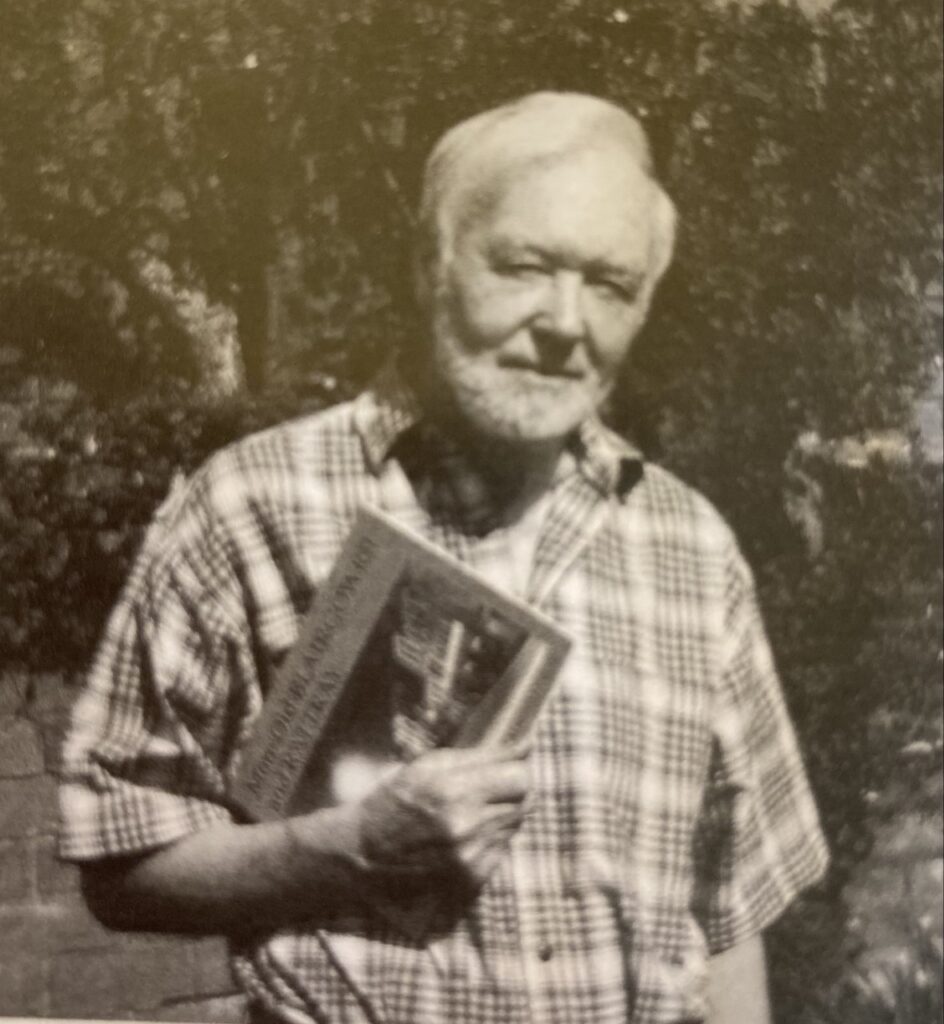

Staff, colleagues and friends of the School of Scottish Studies Archives were very sad to hear of the passing of Maurice Fleming in August last year.

David Fleming, Maurice’s son, has written a touching memorial to his father, which he has asked us to share.

Maurice Fleming, a song-collector from the early days of the School of Scottish Studies, passed away in August 2020.

Maurice was born in the Perthshire town of Blairgowrie in 1926. His father, James, owned a local draper’s shop and the family lived in comfortable circumstances in a house on the town’s Perth Road. Largely self-educated, James R. A. Fleming was an avid book collector with a particular interest in French and Russian literature. The family room at home, always known as the Library, was dominated by large glass-fronted bookcases full of works by the great writers of the day. Maurice’s parents both wrote in their spare time. His father composed reviews, travels sketches and a detective novel; his mother, Jessie, published volumes of poetry. In the 1920s, they collaborated on a successful radio play The Lost Piper which drew on folkloric material and concerned a ghostly musician roaming a warren of tunnels under the city of Edinburgh.

Maurice was educated in Blairgowrie. He left school without any formal qualifications but had developed a love of the written word. As a child, he roamed the fields and woods near his home and became very interested in wildlife, particularly birds. His first ambition was to become a nature writer, following in the footsteps of authors such as H. Mortimer Batten and F. Fraser Darling.

Called up for military service in 1944, Maurice joined the Cameronian Rifle Regiment and began training for service overseas in the Far Eastern Campaign. However, a misfiring Bofors gun shattered his eardrum, rendering him unfit for combat and leaving him with lifelong deafness in one ear. He saw out the war as a lance corporal, serving as a barman in the Officers’ Mess at Fort George and later at Dreghorn Barracks. These postings left him time to pursue his interest in bird-spotting and to enjoy solitary walks in the countryside.

After leaving the army, Maurice pursued a career in hotel management by taking on a number of jobs in hotel kitchens and working for a time in a busy Lyons Corner House off Piccadilly. It was while working at a country hotel in Glen Shee that a colleague suggested he could develop his literary interests by becoming a journalist. In November 1953 he joined the Dundee publishing company D.C. Thomson where he worked on women’s magazines before getting his “dream job” on the staff of The Scots Magazine. He took over as editor from Arthur Daw in 1975 and remained in the post until retirement in 1991.

Maurice’s involvement with the School of Scottish Studies began on the evening of the 26th July, 1954. His old school friend Archy Macpherson had invited him through to Edinburgh to attend a formal dinner in the Adam Rooms, George Street, and quite by chance the two men found themselves sharing a table with Hamish Henderson. Maurice was enthralled by Hamish’s account of the School’s work in seeking out and recording traditional singers and storytellers, and readily agreed to have a go when Hamish suggested he visit the berryfields around Blairgowrie where large numbers of travelling people, still bearers of a folk oral culture, would be at work picking the annual harvest of soft fruit and camping out in fields near his home.

Among the songs Hamish mentioned to look out for was The Berryfields of Blair and Maurice was to find this song and its original author not in a traveller’s camp, but in a small house in Rattray on the other side of the Ericht river from Blairgowrie. The house was occupied by a settled traveller family. Though singers, they were unknown outside the travelling community but they were soon to be internationally famous as the Stewarts of Blair. Maurice made frequent visits to their home, where he recorded Belle Stewart and her daughter Sheila. Belle introduced the young song-collector to many other local singers, and Hamish made trips through from Edinburgh as it became apparent what a wealth of traditional material had been uncovered.

In notes made concerning his memories of Hamish Henderson, Maurice has left us this impression of these exciting times:

“One day I told my mother I was going to a ceilidh that evening.

“Where is it to be held?” she asked, expecting it to be up at the Stewart’s home in Old Rattray or in one of the Blairgowrie hotels.

Instead I told her it was to be at the standing stones on the Essendy Road. This ancient circle is believed to be the only one in the country that has a road running through it. On one side was a raspberry field, and the travellers who had come to pick the fruit had pitched their tents on the grassy strip just over the fence from the road, next to the track leading to the Darroch, now popularly known as the Bluebell Wood. It was on the latter strip that the ceilidh was to take place.

Hamish and Belle Stewart had made the arrangements between them, telling all the pickers on the site and sending word to other singers and musicians camped round about. Hamish, of course, was to be making recordings of the event.

Although it was a warm evening, a few open fires had been lit and the smell of the woodsmoke hung in the air when I walked down the Essendy road. The ceilidh had already begun and I knew the voice of the singer. They had persuaded Jeannie Robertson to come down from her home in Aberdeen.

Hamish always regarded Jeannie as the greatest of his discoveries. A powerful ballad singer, her repertoire was astonishing. And here she was, come to join her friends the Stewarts and other travellers to make a night of it.

But Belle Stewart was on home ground and, surrounded by the crowd, she was at Hamish’s side, ready to point out to him this or that singer who could give what he wanted on his tape.

And, of course, Hamish was loving it all. Watching the two of them it seemed to me that this is how song-collecting should be, a joyous affair, not in some studio but out under the open sky and with the sights, sounds and smells of nature around us.

The ceilidh was still going strong when I rose, stiff, from the ground and bade everyone goodnight.”

Over the next few years, Maurice roamed Perthshire in search of more singers and songs. He often travelled by bike, carrying the heavy tape-machine with him, and made recordings of such distinguished traditional singers as Charlotte Higgins and Martha Reid. Among his most charming field recordings are those he made of the youthful Betty (Dolly) White who he came upon by chance camped out on a hill with her father above the waters of Clunie Loch one sunny day in 1956. (A selection of his Perthshire Field Recordings was released as a CD in 2011.)

During this time, he wrote a series of articles about traveller life and customs. Some of them appeared in the Edinburgh Evening News and The Countryman under the pen name Muiris MacEanruig.

In the late fifties, Maurice moved to Dundee to be nearer his work and was quickly involved in the folk scene there. In 1964, he recorded the singer and fearless political campaigner Mary Brooksbank who was by then a pensioner living quietly with her nephew in a city prefab. The two became friends and Maurice was able to do her a great service by retrieving a manuscript of her writings that had long been in the hands of another singer. This manuscript was to form the basis of Mary’s poetry collection Sidlaw Breezes.

During the 1960s, Maurice was involved in the organisation and hosting of concerts such as that held at the Dundee Art Galleries in July 1961. He also tried his hand at composition and wrote a couple of songs about the old Dundee to Newtyle railway. He was a founder member of Dundee Folk Club but had concerns about the commercialisation of the folk scene and feared that traditional singers were being squeezed out by popular entertainers. These concerns, shared by others at the time, led him to help form and work for the Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland. With the renowned song-collector and singer Pete Shepheard as its guiding light, the TMSA aimed to give a platform to grassroots musicians and singers by running a number of locally based ceilidhs and other events. These included the now legendary Blairgowrie Festivals of Traditional Music and Song which were held each August between 1966–70. Maurice’s intimate knowledge of Blairgowrie performers and venues, along with his journalistic skills, help to ensure the success of these events. He also collaborated with Pete in collecting material for a Dundee Song Book. The fruits of this collaboration were to form part of Nigel Gatherer’s Songs and Ballads of Dundee.

Maurice had a great love of the theatre. He wrote plays for both the professional and amateur stage. His debut, The Runaway Lovers, which was produced at Dundee Rep in 1956, drew on his experiences in the hotel trade and was inspired by legends of Grainne and Diarmid which he found circulating within the oral tradition of Glen Shee.

His other plays included The Comic, set during the dying days of Variety Theatre; The Assembly Murder, a fast-moving Edinburgh thriller; and the highly popular Me and Morag, about a spirited young woman who shakes up a stuffy Edinburgh publishing house – produced at Perth Theatre in 1990. His last performed play, The Haunting O’ Middle Mause, (1992) was based on historical records of strange occurrences at a farm near Blairgowrie in the early eighteenth century and incorporated folksong material. Amongst his unperformed work was a one-man-play concerning the life of the Blairgowrie-born covenanter Donald Cargill. With the exception of a one-act play about Anne Frank, all Maurice’s plays were set in Scotland and celebrated the Scots language and people.

Maurice enjoyed a long and fruitful retirement after leaving The Scots Magazine. He wrote books on local folklore for the Mercat Press – The Ghost O’Mause and other Tales and Traditions of East Perthshire (1995) and The Sidlaws: Tales, Traditions and Ballads (2000) as well as a more general work, Not of This World: Creatures of the Supernatural in Scotland (2002). There was also a book for younger readers, The Real Macbeth and other Stories from Scottish History (1997), and a torrent of freelance journalism for a variety of newspapers and magazines.

A founding member of Blairgowrie, Rattray and District Civic Trust, he served as Chairperson for a number of years and was deeply involved in the successful campaign to establish the authenticity of the Essendy Road Standing Stone Circle and prevent its removal elsewhere to facilitate traffic. This took eight years and involved a good deal of patience dealing with various interested parties. Having gained the necessary permissions, an archaeologist was employed to survey the Stones and confirm their prehistoric credentials.

Maurice played a leading role in another local controversy in 2006 when an historic trophy, known as the Rattray Silver Arrow, was in danger of being sold at Southeby’s by its then custodian who considered himself its owner. The affair attracted national press attention and was the subject of a public debate chaired by John Swinney MSP during which Maurice successfully put the case for the Arrow being the rightful property of the People of Rattray.

A keen postcard collector, Maurice compiled two books of old Blairgowrie and Rattray Cards for Stenlake Publishing, and over the years assembled a comprehensive visual record of his home town and district. The collection now rests in the archive of the A.K. Bell Library in Perth.

Maurice married Nanette Dalgleish in 1958 and the couple were together for 59 years until Nanette passed away in 2017. They had three children: Gavin, David and Airlie.

His final years were darkened by the loss of Nanette and the onset of several health issues but he was able to continue living at his home in Blairgowrie until a few weeks before his death. He retained a love of folk music and always thought of his collecting days as some of the happiest and most exciting of his life.

Maurice was modest about his achievements, courteous in his dealings with others, and generous with his time in helping aspiring writers. In his own quiet way, as song collector, journalist, dramatist and folklorist, he carved a legacy for himself across several facets of Scottish cultural life.

David Fleming

You can find over 120 of Maurice’s recordings from The School of Scottish Studies online, via Tobar an Dualchais.