Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 16, 2025

Marking up collections sites with Schema.org

This blog was written by Holly Coulson, who is working with Nandini Tyagi on this project.

For the last three months, I have been undergoing a Library Metadata internship with the Digital Development team over in Argyle House. Having the opportunity to see behind the scenes into the more technical side of the library, I gained far more programming experience I ever imagined I would, and worked hands on with the collections websites themselves.

Most people’s access to University of Edinburgh’s holdings is primarily through DiscoverEd. But the Collections websites exist as a complete archive of all of the materials that Edinburgh University have, from historical alumni to part of the St Cecilia’s Hall musical instrument collection. These sites are currently going through an upgrade, with new interfaces and front pages.

My role in all of this, along with my fellow intern Nandini, was to analyse and improve how the behind-the-scenes metadata works in the grander scheme of things. As the technological world continually moves towards linked data and the interconnectivity of the Internet, developers are consciously having to update their websites to include more structured data and mark-up. That was our job.

Our primary aim was to implement Schema.org into the collections.ed.ac.uk spaces. Schema, an open access structured data vocabulary, allows for major search engines, such as Google and Yahoo to pull data and understand what it represents. For collections, you can label the title as a ‘schema:name’ and even individual ID numbers as ‘schema:Identifier’. This allows for far more reliable searching, and allows websites to work in conjunction with a standardised system that can be parsed by search engines. This is ultimately with the aim to optimise searches, both in the ed.ac.uk domain, and the larger search engines.

Our first major task was the research. As two interns, both doing our Masters, we had never heard of Schema.org, let alone seen it implemented. We analysed various collections sites around the world, and saw their use of Schema was minimal. Even large sites, such as the Louvre, or the National Gallery, didn’t include any schema within their record pages.

With minimal examples to go off, we decided to just start mapping our metadata inputs to the schema vocabulary, to get a handle on how Schema.org worked in relation to collections. There were some ideas that were very basic, such as title, author, and date. The basics of meta-data was relatively easy to map, and this allowed us to quickly work through the 11 sites that we were focusing on. There were, however, more challenging aspects to the mapping process, which took far longer to figure out. Schema is rather limited for its specific collection framework. While bib.schema exists, an extension that specifically exists for bibliographic information, there is little scope for more specific collection parameters. There were many debates on whether ‘bib.Collection’ or ‘isPartOf’ worked better for describing a collection, and if it was viable to have 4 separate ‘description’ fields, for different variations of abstracts, item descriptions, and other general information.

The initial mappings for /art, showing relatively logical and simple fields

More complicated mappings in /stcecilias, with a lot of repetition and similar fields, and ones that were simply not possible, or weren’t required.

There were other, more specific, fields we had to deal with, that threw up particular problems. The ‘dimensions’ field is always a combined height and width. Schema.org, with regards to specific dimensions, only deals with individual values: a separate height and a separate width value. It wasn’t until we’d mapped everything that we realised this, and had to rethink our mapping. There was also many considerations for if Schema.org was actually required for every piece of metadata. Would linking specific cataloguing and preservation descriptions actually be useful? How often would users actually search for these items? Would using schema.org actually help these fields? We continually had to consider how users actually searched and explored the websites, and whether adding the schema would aid search results. By using a sample of Google Analytics data, we were able to narrow down what should actually be included in the mapping. We ended up with 11 tables, for 11 websites (see above), offering a precise mapping that we could implement straight away.

The next stage was figuring out how to build the schema into the record pages themselves. Much of the Collections website is run on PHP, which takes the information directly from the metadata files and places them in a table when you click on an individual item. Schema.org, in its simplest form, is in HTML, but it would be impossible to go through every single record manually and mark it up. Instead, we had to work with the record configuration files to allow for variables to be tested for schema. If they were a field with a schema definition, the schema.org tag is printed around it, as an automated process. This was further complicated by filters that are used, meaning several sets of code were often required to formulate all the information on the page. As someone who had never worked with PHP before, it was definitely a learning curve. Aided by various courses on search engine optimisation and Google Analytics, we were becoming increasingly confident in our work.

Our first successes were uploading both the /art and /mimed collections schema onto the test servers, only receiving two minimal errors. This proved that our code worked, and that we were returning positive results. By using a handy plugin in Chrome, we were able to see if the code was actually offering readable Schema.org that linked all of our data together.

The plugin, OpenLink Structured Data Sniffer, showing the schema and details attributed to the individual record. In this case, Sir Henry Raeburn’s painting of John Robison.

As we come to the final few weeks of our internship, we’ve learnt far more about linked data and search engine optimisation than we imagined. Being able to directly work with the collections websites gave us a greater understanding of how the library works overall. I am personally in the MSc Book History and Material Culture programme, a very hands-on, physical programme, and exploring the technical and digital side of collections has been an amazingly rewarding experience that has aided my studies. Some of our schema.org coding will be rolled out to go live before we finish, and we have realised the possibilities that structured data can bring to library services. We hope we have allowed one more person to find the artwork or musical instrument they were looking for. While time will tell how effective schema.org is in the search results pages, we are confident that we have helped the collections become even more accessible and searchable.

Holly Coulson (Library Digital Development)

Database trials – China Core Newspapers & The Eastern Miscellany

China Core Newspapers provides the full-text articles from 633 current newspapers in China from 2000 onwards. The database is updated daily. The trial can be accessed by going to the China Core Newspapers entry in the Library’s Databases A-Z list, or simply click here. The trial will end on 31 July 2018.

The Eastern Miscellany (《東方雜誌》) was an iconic periodical of the Commercial Press from 1904 to 1948. It is highly regarded as a very important resource for the study of the modern history of China. The database includes the full 44 volumes (819 issues), with over 30,000 articles, 12,000 pictures, and over 14,000 advertisements. Articles cannot be downloaded directly, but the full texts of the articles can be copied and pasted. To access the trial, please click here on the University network. The trial will also be advertised on the Library’s E-resources Trials website. The trial will end on 21 July 2018.

Feedback would be appreciated.

Session Paper Project Internship

My name is Claire and I am the first intern to work with Nicole on the Session Papers Project. I am due to graduate with a master’s degree in paper conservation this year, but I am starting this internship to broaden my knowledge of book conservation. Methods and skills within conservation tend to overlap, and this is especially true with books and paper. My role within this pilot project is to assist in the conservation of 300 books. Conservation treatments include structural repairs, consolidation, and board reattachment. The volumes need to be in a good enough condition to withstand digitisation and further handling following the project.

Claire working in the conservation studio

Scotland’s languages: Pronunciation and purity

In the last post we looked at predominantly Gaelic, Scots and English speaking parishes. But, it is important to note that the other minority languages have impacted on whatever the majority language was, including its pronunciation and intonation. The linguistic landscape of Scotland’s parishes was far from black and white. For some of those writing the parish reports, the jumble of languages used was an unwelcome development, as they saw it as an erosion of the “superior” pure form of language.

Pronunciation

It has been fascinating to find out how people pronounced words. Several parish reports give us a idea of the kinds of sounds produced, in the various Scots dialects in particular. Again, it is other languages which greatly influenced pronunciation.

In Wick, County of Caithness, “the language spoken over all the parish is, with exception of that of some Gaelic incomers, a dialect of the lowland Scottish. It is distinguished, however, by several peculiarities. Wherever the classical Scottish has wh, the dialect of the parish of Wick has f; as fat for what, fan for whan; and wherever the Scottish has u, this dialect has ee ; as seen for sune, meen for mune, feel for fule. Ch at the beginning of words is softened into s, or sh; as, surch for church; shapel for chapel. Th at the beginning of words is often omitted. She, her, and hers are almost invariably used for it and its. This seems a Gaelic idiom; and the tendency to pronounce s and ch, as sh, seems a relic of Gaelic pronunciation.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 144)

Jedburgh, County of Roxburgh – “The common people in the neighbourhood of Jedburgh pronounce many words, particularly such as end in a guttural sound, with a remarkable broad, and even harsh accent. They still make use of the old Scotch dialect. Many of the names of places, however, are evidently derived from the Erse, and expressive of their local situation in that language. For instance, –Dunian, John’s Hill; –Minto, Kids Hill; –Hawick, Village on a River; –Ancrum, anciently called Alnicromb a Creek in the River; etc. etc.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 15)

Wilton, County of Roxburgh – “The language generally spoken by the lower orders, throughout this district, contains many provincialisms, but these are becoming gradually obsolete. Two diphthongal sounds, however, seem still to maintain their ground, namely, those resembling the Greek eǐ, and the ow, as in the English words, cow, sow, how, now,–e.g. the common people generally pronounce, tree, treǐ; tea, teǐ; knee, kneǐ; me, meǐ; and, instead of the diphthongal sound of oo in the pronoun you, the pronunciation is almost invariably yow, as in now.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 78)

Dalgety, County of Fife – “The language commonly spoken in the parish is the Old Scotch dialect, and there seem to be no peculiar words or phrases which are not in general use throughout most parts of the kingdom. The words are pronounced with a broad accent; and I have often heard in this part of the country a sound given to the diphthong oi, which is not, I believe, so usual in other places: it is frequently pronounced as if it consisted of the letters ou, as for boul boil, pount for point, vauce for voice, etc.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 265)

Caputh, County of Perth – “The Stormont dialect, of course, prevails, in which the chief peculiarity that strikes a stranger is the pronunciation of the Scotch oo as ee, poor being pronounced peer, moon meen, aboon abeen, &c.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 677)

Dunlop, County of Ayrshire – “The language which they speak is a mixture of Scotch and English, and has no other singularity, but the slow drawling manner in which it is spoken, and that they uniformly pronounce fow, fai-w, and mow, mai-w.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 541)

Alves, County of Elgin – “The language generally spoken is the Scotch. A stranger is struck with the peculiar vowel sounds, given in a great many words, as wheit for wheat, feel for fool, pure for poor, and wery for very, &c.” (NSA, Vol. XIII, 1845, p. 107)

Montrose, County of Forfar, “One great peculiarity which strikes a stranger from the south, in the language of the common people in this county, and in the neighbouring counties on the north, is the use of f for wh, as fan, far, &c. for when, where, &c. Except by the better classes, the lowland Scotch is universally spoken with a strong provincial accent.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 279)

The Buchan dialect is mentioned in several parish reports from the County of Aberdeen. It is also known as the Doric dialect, and is a sub-dialect of Northern Scots, found in a small area between Banff and Ellon. In Peterhead, County of Aberdeen, “the language spoken in this parish is the broad Buchan dialect of the English, with many Scotticisms, and stands much in need of reformation, which it is to be hoped will soon happen, from the frequent resort of polite people to the town in summer.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 592) People in the parish of Aberdour, County of Aberdeen, also spoke “the broad Buchan, or real Aberdeenshire, and this dialect is much the same as it was forty years ago.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 266) For more information on the Buchan dialect take a look at the parish report for Longside, County of Aberdeen. (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 294)

Intonation is also described in some of the parish reports. In Dunfermline, County of Fife, “the language is a mixture of Scotch and English. The voice is raised, and the emphasis frequently laid on the last word of the sentence.”(OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 479) A similar observation was also made in the report for Lesmahago, County of Lanark. “The language spoken is the broad Scotch dialect, with this peculiarity, very observable to strangers, that the voice is raised, and the sound lengthened upon the last syllable of the sentence.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 433)

Purity

Some writers of the parish reports had a very clear perception of language purity and, conversely, corruption. Inhabitants in many parishes were considered to be speaking a language that was not in its pure and correct form.

- Lochgoil-Head and Kilmorich, County of Argyle – “The Gaelic that is spoken in this place, owing to the frequent communication with the Low Country, is corrupted with a mixture of English words and phrases, and is not so pure, nor so correct, as that which is spoken in the more remote parts of the Highlands.” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 190)

- Logierait, County of Perth – “The language spoken here, is a corrupted dialect of the Gaelic. The Saxon dialect of the lowlands is, however, pretty generally understood here.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 82)

- Comrie, County of Perth – “All the young people can speak English; but, in order to acquire it, they must go to service in the Low Country. The Gaelic is not spoken in its purity, neither here nor in any of the bordering parishes.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 186)

View on the Earn, Comrie, Scotland. Taken between ca. 1890 and ca. 1900. By The Library of Congress [No restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons.

- Fortingal, County of Perth – “The Gaelic is the language of the natives. It is, however, losing ground, and losing its purity, very much of late. Forty years ago, in some parts of the parish, especially in the district of Rannoch, it was spoken in as great purity as in any district of the Highlands. That race of genuine natives having disappeared, many of their phrases and idioms have become almost unintelligible to the rising generation. It is, however, gratifying to the antiquary and to the lover of Celtic literature, that so much has been done to rescue the language and insure its permanency and stability; still all that is practicable has not yet been achieved. Hundreds of vocables might be collected which have escaped the notice of the several learned compilers of our Gaelic dictionaries.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 553)

- Halkirk, County of Caithness – “[Erse] is much corrupted, but yet spoken with great fluency and emphasis, and not without harmony of sound. [English] has also many words, which are neither English nor Scotch, yet, according to its idiom, it is spoken with great propriety, and the sentiments are expressed by it, either in narration or description, as intelligibly and significantly, as in any county in Great Britain, nay, I dare say, more so than in most of them. These languages are spoken in various degrees.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 62)

- Eddlestone, County of Peebles – “The language generally spoken is a corrupt Scotch, with a barbarous admixture of English. A few only of the oldest of the people speak the Scottish dialect in its purity. These, however, are rapidly disappearing, and in a few years more in all probability there will not be one person alive who could have held converse with his grandfather without the aid of a dictionary.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 149)

- Evie and Rendall, County of Orkney – “In the language of the people, there is an intermixture of Norse words with Scotch and English; but, on the whole, they speak more correctly than the peasantry do in other parts of Scotland. The accent is peculiar though far from being unpleasant.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 202)

In the parish report for Kilmalie, County of Inverness, it was noted that “it is remarkable, yet not the less true, that the illiterate Highlander, who is a stranger to every other language but the Gaelic, speaks it more fluently, more elegantly, and more purely, than the scholar.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 430)

In some cases, inhabitants were strongly criticised for speaking impure languages, especially those of Kilmadock, County of Perth!

- Kirkmichael, County of Perth – “The prevailing language in the parish is the Gaelic. A dialect of the ancient Scotch, also, is understood, and currently spoken. These two, by a barbarous intermixture, mutually corrupt each other.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 516)

- Kilmadock, County of Perth – “The language of the common people in this parish, like many of the parishes in the neighbourhood, is a mixture of Scotch and English. This jargon is very unpleasant to the ear, and a great impediment to fluent conversation. No language is more expressive than the Scotch, when spoken in perfection; and, though the ancient be short and unmusical, yet it is by no means disagreeable to hear two plain country men conversing in the true Scotch tongue; but, in this parish, you seldom meet with such instances... In the quarter towards Callander, the generality of the inhabitants speak Gaelic; and this is perhaps still more corrupt than even the Scotch, in the other quarters of the parish. It is impossible to conceive any thing so truly offensive to the ear, as the conversation of these people. The true Gaelic is a noble language, worthy of the fire of Ossian, and wonderfully adapted to the genius of a warlike nation; but the contemptible language of the people about Callander, and to the east, is quite incapable of communicating a noble idea… It ought, therefore, to be earnestly recommended to the people of this parish, and, indeed, to other parishes in that quarter, to study a more perfect style; either to practice the true Gaelic, the true Scotch, or the true English tongue. But all kinds of civilization in society go hand in hand; and when arts and sciences begin to flourish here, the language will gradually polish and refine.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 53)

Language trends

A couple of parishes reported a particularly interesting development, that of younger Gaelic speakers interspersing their language with English or Scots words. In North Uist, County of Inverness. “The language spoken is the Gaelic, which the people speak with uncommon fluency and elegance. One fifth of the whole population above the age of twelve years understand and speak English. Such of them as are in the habit of going to the south of Scotland for trading or for working, are fond of interlarding some English or Scotch phrases with their own beautiful and expressive language. This bad taste is confined to so limited a number, that it has but slightly affected the general character of their native tongue. There are only five individuals in the parish who do not understand the Gaelic, and some of these have made considerable progress in its attainment.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 172) In Gairloch, County of Ross and Cromarty, “some young men, indeed, who have received a smattering of education, consider they are doing great service to the Gaelic, by interspersing their conversation with English words, and giving them a Gaelic termination and accent. These corrupters of both languages, with more pride than good taste, now and then, introduce words of bad English or of bad Scotch, which they have learned from the Newhaven or Buckie fishermen, whom they meet with on the coast of Caithness during the fishing season. The Gaelic, however, is still spoken in as great purity by the inhabitants in general, as it was forty years ago.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 95)

In some cases, however, the impure form of language at least made it easier for certain groups of people to understand. In Rogart, County of Sutherland, “a considerable proportion of the inhabitants, however, can converse in the English language; and, in a few years it is likely that none may be found who cannot do so. Their English, being acquired from books, and occasional conversation with educated persons, is marked by no peculiarity, except a degree of mountain accent and Celtic idiom; so that it is more easily intelligible to an Englishman than the dialect spoken by the Lowland Scotch.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 51)

Conclusion

Languages are very fluid, with changes occurring over time in vocabulary, pronunciation and intonation. In some parish reports there are some strong comments bemoaning the lack of language purity, but the pure form of a language is an ideal, not a reality. This is certainly the case in Scotland where the Gaelic, Scots, English and Scandinavian languages influenced each other.

Changes were even felt between the first and second Statistical Accounts of Scotland, most notably the increased comprehension and use of English. In the final post on Scotland’s languages we look look more closely at the reasons for linguistic change.

A Stitch in Time: Mahābhārata Delivered Online

I don’t know if I have ever been more excited about a digitisation project going live: the Edinburgh University’s 1795 copy of the Mahābhārata is now available online. This beautiful scroll is one of the longest poems ever written, containing a staggering 200,000 verses spread along 72 meters of richly decorated silk backed paper. As one of the Iconic items in our Collection it was marked as a digitisation priority, so when a customer requested the 78 miniatures back in April 2017 it seemed like a good opportunity to digitise it in its entirety. There was just one problem: it was set to go on display in the ‘Highlands to Hindustan’ exhibition, which opened at the Library in July. This left us with only a narrow window of opportunity for the first stages of the project: conservation and photography. Read More

Scotland’s languages: Gaelic, Scots and English

This is the second post on Scotland’s languages. This time we look more closely at the languages spoken throughout the parishes. As can be gleaned in the last blog post, at one point the majority of Scots spoke Gaelic, or Erse as this was called in some of the parish reports. According to the authors of the Statistical Accounts, Gaelic was more widely spoken in many parishes. But there were also areas of Scotch or Scots speakers, with English beginning to make strong inroads.

Predominantly Gaelic-speaking parishes

There were many parishes where most inhabitants spoke Gaelic, including:

- Barvas, County of Ross and Cromarty (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 147);

- Moy and Dalarossie, County of Inverness (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 499);

- Applecross, County of Ross and Cromarty (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 102)

- Gairloch, County of Ross and Cromarty – “The Gaelic is the prevailing language in this, as well as in several other corners on the West coast” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 93);

- Inverary, County of Argyle – “The language generally spoken is the Gaelic. Among the agricultural labourers, it is almost exclusively used; and as many of them, for various reasons, remove from the country into the burgh, they naturally continue to speak their mother tongue, and to teach it to their children.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 27).

Brown, William Beattie; Coire-na-Faireamh, in Applecross Deer Forest, Ross-shire; 1883-84. Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/coire-na-faireamh-in-applecross-deer-forest-ross-shire-186783

However, this situation was beginning to change. If you look at the parish reports for Gigha and Cara, County of Argyle, you can see the differences in language use even between the Old and New Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

“The language of the common people is Gaelic, but not reckoned the purest, on account of their vicinity, to Ireland, and intercourse with the low country, by which many corruptions have been introduced into their phraseology. They understand English, and several speak it well enough to transact business; but very few of them can understand a connected discourse in that language.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 65)

“English, however, is much better understood by young and old than it was forty years ago, but there are not above ten persons in the parish who do not understand and speak Gaelic.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 401)

By the time of the New Statistical Accounts, in practically all of the parishes English was increasingly understood and spoken. It is always interesting when figures, even approximations, are provided. In Southend, County of Argyle, “the language generally spoken by two thirds of the people is Gaelic; but, from the establishment of schools and the intercourse with Campbelton, and the Lowland districts of Scotland, the English language is beginning to be universally understood. Families who understand Gaelic best, 210; English best, 145.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 431)

We will be looking at the rise of the English language in the next post.

Predominantly Scotch/Scots-speaking parishes

Scots is a Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and some areas of Ulster. It is itself “a dialect of the Dano-Saxon, which was brought from the other side of the German Ocean, by the Danish invaders of the ninth and eleventh centuries”. (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 226) Here are some examples of parishes which were predominantly Scots-speaking. Again, we can see that in many cases other languages have also left their mark.

- New Spynie, County of Elgin (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 637)

- Cromarty, County of Ross and Cromarty – “The language of all born and bred in this parish, approaches to the broad Scotch, differing, however, from the dialects spoken in Aberdeen and Murrayshire; this being one of the three parishes in the counties of Ross and Cromarty, in which, till of late years, the Gaelic language, which is the universal language in the adjacent parishes, was scarce ever spoken. There has been a considerable change, of late years, in this respect, among the inhabitants here; the Gaelic having become rather more prevalent than usual.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 254) This was attributed to Gaelic-speaking people coming to work in the parish.

- Kirkmichael, County of Ayrshire – “The language is a mixture of Scotch and English, without any particular accent. In this district, as in every other, there are certain provincial words and phrases peculiar to itself.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 111)

- Drainie, County of Elgin – “The only language here is Scotch; but the pronunciation is gradually approaching nearer to the English. Gaelic is not spoken nearer than 20 miles; and very few

of the names of places here seem derived from it.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 87) - Boharm, County of Banff – “The Scotch is the only language spoken in the parish; but, with a few exceptions, the names of the places belong to the Erse tongue.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 362)

- Tannadice, County of Forfar – “The broad Scotch is the only language spoken here. Some of the names of places are Gaelic, and others of Gothic origin; although the former seems to abound most.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 380)

- Kinfauns, County of Perth – “The language of this parish and corner is Saxon, intermixed with Scottish words and expressions; attended, however, by little or no provincial accent or dialect. Though this part of the country is not at a great distance from the Highlands, yet neither Gaelic words nor accent are known amongst the natives below Perth. Very few names of places are Erse; but great number are Scotch or Saxon.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 223)

- Canisbay, County of Caithness – “The Scotch, with an intermixture of some Norwegian vocables, is the only language spoken in the parish… There is scarcely a place in the whole parish, whose name is not of Norwegian derivation.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 162)

- New Machar, County of Aberdeen – “The common people speak the Scotch language, and in what is commonly called, and well known by the name of, the Aberdonian Dialect.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 470)

Nasmyth, Alexander; Robert Burns; 1821-22. National Portrait Gallery, London; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/robert-burns-157341

In some parish reports, particular Scots pronunciation was remarked upon. In Gamrie, County of Banff, “the language spoken in this parish is the Scottish, with an accent peculiar to the north country. There is no Erse.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 477) In Dron, County of Perth, “the language spoken here is Scotch, with a provincial accent or tone; the pronunciation rather slow and drawling, and apt to strike the ear of a stranger as disagreeable.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 478) Scots spoken in the county of Fife also had its own pronunciation. In Carnock, County of Fife, “the language now generally spoken in this district, is the broad Scotch dialect, with the Fifeshire accent, which gives some words so peculiar a turn, as to render the speaker almost unintelligible to the natives of a different county.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 496) In St Andrews and St Leonards, County of Fife, “the language of this parish is the common dialect of the Scotch Lowlands. The Fifans are said, by strangers, to use a drawling pronunciation, but they have very few provincial words.”(OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 215) Specific examples of pronunciation will be given in the next post on Scotland’s languages.

Predominantly English-speaking parishes

What is particularly interesting to note about the predominantly English-speaking parishes is that, for the most part, they do not actually border England! (Read the next post to look at possible reasons why.) Again, there are influences from other languages, such as Gaelic and Scots, and Norse in the Shetland Isles.

- Cushnie, County of Aberdeen – “English is the only language now known in the parish, the Gaelic having ceased to be understood.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 177)

- Ardersier, County of Inverness – “The language generally spoken in the village, which contains three-fourths of the population of the parish, is English. In the interior, Gaelic prevails. But, from recent changes in the lessees of farms, and from the new occupants possessing little of the Celtic character, it may be fairly stated, that the Gaelic has lost, and is losing ground.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 472)

- Newbattle, County of Edinburgh (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 70)

- Broughton, County of Peebles – “The language spoken here is English, with the Scotch accent.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 158)

- Kirkconnell, County of Dumfries – “only the English language is now spoken here, as in the rest of Nithsdale, with considerable purity, excepting chiefly a few old Scotch, or rather obsolete Saxon words, that now and then occur; and in a plain, easy, manly style of pronunciation, without any of those grating peculiarities of provincial accent, that mark the dialect of some of the adjoining counties. With the small exception, of one from England, and another from Ireland, the inhabitants are all natives of Scotland.” (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 447)

- Portpatrick, County of Wigton – “English is spoken in this parish, with less of provincial accent and less mixture of Scotch than in the more central and populous districts of Scotland.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 145)

- Section on the county of Shetland from volume 15 in account 2 – “The language is English, with the Norse accent, and many of its idioms and words.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 156)

Here, we should mention that there seems to be some confusion between the English language and the Scots dialect. In some quarters, Scots is seen as a dialect of English, or even “English or Saxon, with a peculiar provincial accent” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 193), instead of it being a language in its own right. This makes it a little difficult to identify those parishes speaking English and those speaking Scots. Examples include:

- Bellie, County of Elgin – “The Gaelic tongue, however, has long disappeared in this part of the country; the language, in general, being that dialect of English common to the North of Scotland; though, among all persons who pretend to anything like education, the English language is daily gaining ground.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 264)

- Luss, County of Dumbarton -“The language now universally spoken by the natives of the parish is the English language, or rather the provincial Scotch dialect.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 162)

- Speymouth, County of Elgin – “The language here spoken is the English, if the broad Scotch that is spoken throughout the greatest part of Murray, Banff, and Aberdeenshires, be thought entitled to that name. Erse is not the common language within 20 miles of us.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 406)

- Keith, County of Banff – “In this parish, and in all the neighbourhood, the language spoken is the Scotch dialect of the English language.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 423)

Language differences within parishes

As well as language differences between parishes, there are differences within parishes. In the parish of Luss, County of Dumbarton, “south from Luss, English, and north from it the Gaelic, is the prevailing language.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 266) Here are some other inter-parish variations:

- Keith, County of Banff – “All the old names of places are evidently derived from the Gaelic, which language is generally spoken in a detached corner of the parish, by a colony from various districts of the Highlands; who being indigent, and supported by begging, or their own alertness, are allured there by the abundance of moss, and the vicinity of a very populous and plentiful country.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 423)

- Little Dunkeld, County of Perth – “In that part of the parish which is below lnvar, the people speak the Scottish dialect of the English, and are not distinguished by any perceptible shade of character from the inhabitants of the low country parishes around them. The rest of the inhabitants (more than three fourths) are Highlanders, who speak a dialect, not perhaps the purest, of the Gaelic. They have all a strong attachment to their native tongue; many speak English with tolerable case, and the youth, by means of the charity schools, can write it with rather more propriety, and copiousness than those of the low country part of this parish, who are very all situated with respect to schools.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 369)

- Dowally, County of Perth – “It is curious fact, that the hills of King’s Seat and Craigy Barns, which form the lower boundary of Dowally, have been for centuries the separating barrier of these languages. In the first house below them, the English is, and has been spoken; and the Gaelic in the first house, (not above a mile distant), above them.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 490)

- Edenkillie, County of Elgin – “In the lower part of the parish, the Scotch dialect of the English language is only spoken; but, in the upper part, the Gaelic is still much in use. About 50 years ago, the minister preached the one half of the day in English, and the other half in Gaelic.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 566)

- Strathdon, County of Aberdeen – “The language spoken is English, or rather broad Scotch, excepting in Curgarff. The people there, especially in the upper part of that district, speak also a kind of Gaelic; but that language among them is much on the decline.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 183)

- Monzie, County of Perth – “This parish being situated on the borders of the Highlands, and having much intercourse and connection with the natives, we need not be surprised to find that the Gaelic is spoken in the back part of it, and the old Scotch dialect in the fore part, pronounced with the Gaelic tone and accent. There are, however very few persons in the whole parish, who do not either speak or understand Gaelic.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 251)

- Dunkeld, County of Perth – “The English language is spoken in Dunkeld. In Dowally, with the exception of 110 persons, English is spoken with fluency, but they prefer Gaelic. Gaelic is still preached, and it is taught, along with English, at school.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 989)

- Crieff, County of Perth – “The people speak the English language in the best Scotch dialect: although the Gaelic be commonly spoken at the distance of three miles north, of four west from Criess, yet no adult natives of the lowland part of the parish can either speak or understand it. They have not even contracted the peculiar tone of that language, by their intercourse with the numerous Highland families now residing in the town. Many indeed of these understand no other language but the Gaelic, and their children born in Crieff speak that alone for a few years as their mother-tongue.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 601)

Conclusion

It has been very interesting to discover the language similarities and differences between parishes and even within parishes. It is clear that, even though parishes were predominantly Gaelic, Scots or English speaking, other languages were influencing what was being spoken. In the next post, we will look at the concept of language purity and, conversely, corruption, as well as specific examples of pronunciation found in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

Fitba’ crazy, fitba’ mad? A football inspired reading list (yet again!)

The 2018 World Cup kicks off today in Russia and to mark this occasion we decided to resurrect and update our football inspired reading list that we originally published just over 2 years ago when Euro 2016 began (and 2 years before that when the 2014 World Cup started – don’t say we don’t have any new ideas!) These are just a small number of the e-books currently available to staff and students of the University in the Library’s collections that look at different aspects of the beautiful (or not so beautiful) game from a social sciences perspective.

Football and supporter activism in Europe: whose game is it? edited by

Marketing and football: an international perspective edited by Michel Desbordes and Simon Chadwick examines in two parts the study of football marketing in Europe and the development of a marketing dedicated to football, with the question of the European example being used worldwide.

Football hooliganism, fan behaviour and crime: contemporary issues edited by Matthew Hopkins and James Treadwell focuses on a number of contemporary research themes placing them within the context of palpable changes that have occurred within football in recent years. The collection brings together essays about football, crime and fan behaviour from leading experts in the fields of criminology, law, sociology, psychology and cultural studies. Read More

Correcting Shakespeare

Since November last year, I have been volunteering on the Luna Project in the Digital Imaging Unit. Throughout the project I have been working with the University of Edinburgh’s Shakespeare Collection. As a fan of Shakespeare’s work, I was delighted to have the opportunity to work closely with this collection which contains a variety of different classic Shakespeare plays such as; Romeo and Juliet, Henry VI, Midsommer Night’s Dreame and my personal favourite, the Taming of The Shrew. Read More

Since November last year, I have been volunteering on the Luna Project in the Digital Imaging Unit. Throughout the project I have been working with the University of Edinburgh’s Shakespeare Collection. As a fan of Shakespeare’s work, I was delighted to have the opportunity to work closely with this collection which contains a variety of different classic Shakespeare plays such as; Romeo and Juliet, Henry VI, Midsommer Night’s Dreame and my personal favourite, the Taming of The Shrew. Read More

D-Day anniversary: Norman memories in the archives

A more personal take on our archives…

As any archivist knows, you can sometimes stumble upon archives with an unexpected and personal connection: this was the case for me when I found out that in the Special Collections of the Library was an album containing 175 photographs and postcards showing my home city, Caen, before and during the Second World War (Coll-164)… It immediately reminded me of my own grandparents, who had lived through the occupation, the bombing and finally the liberation of this medium-sized Norman city. They would always tell me stories about life during the war, and describe the way Caen looked before it: indeed, about 80 percent of the city was destroyed, in particular during the controversial bombing raid that preceded the ‘Operation Charnwood’ in July 1944.

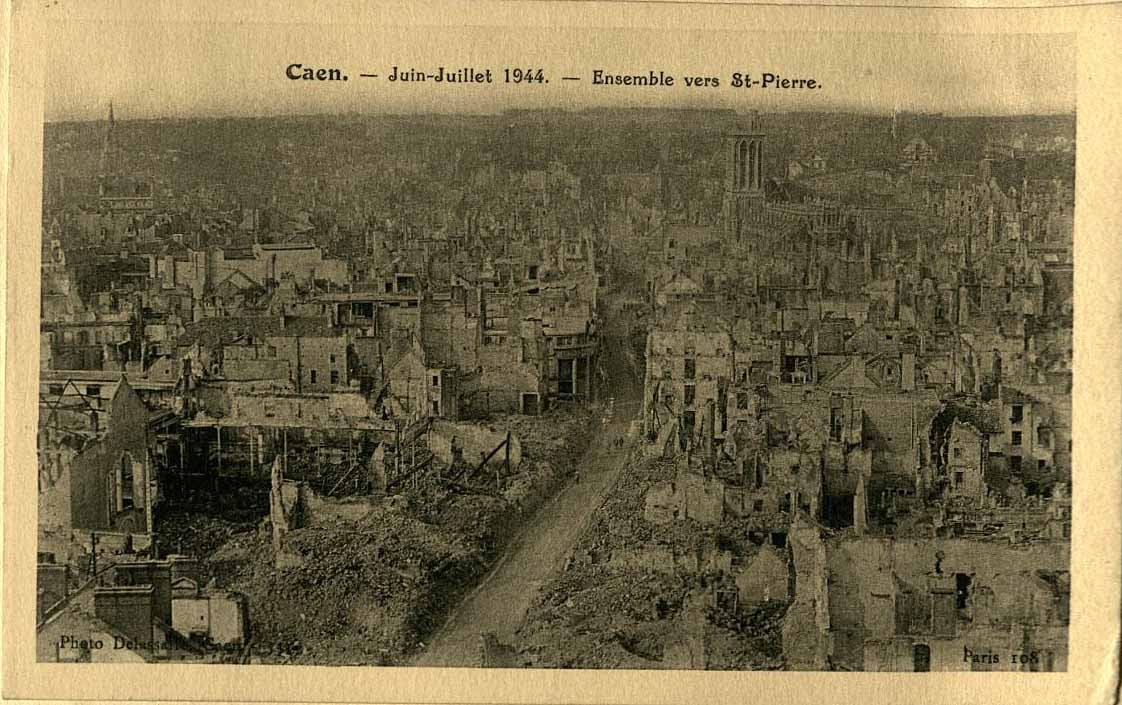

Aerial view of Caen after the bombings in July 1944 (Coll-164/4)

As you can see in the picture, the city was ravaged. The central area around the castle, St Pierre Church, and the neighbourhood called îlot St Jean were particularly affected. Post-war Caen looks like a field of ruins, and I was moved when I browsed the album for the first time and saw the full extent of the devastation. When it happened my grandmother, who was around 15 at the time, had taken shelter in a town a few kilometres away; but my grandfather was there and took part in the rescue effort to help searching the rubbles for survivors. He was only 18.

Looking through the album, I was able to recognise a few familiar buildings amid the destruction: churches, streets, houses, the castle… I knew exactly where these were and what they looked like now. I found the comparison really interesting, and this is why I decided to do a little before/after photo shoot when I went home for the Christmas holidays.

St Pierre Church and surrounding area (Coll-164/58)

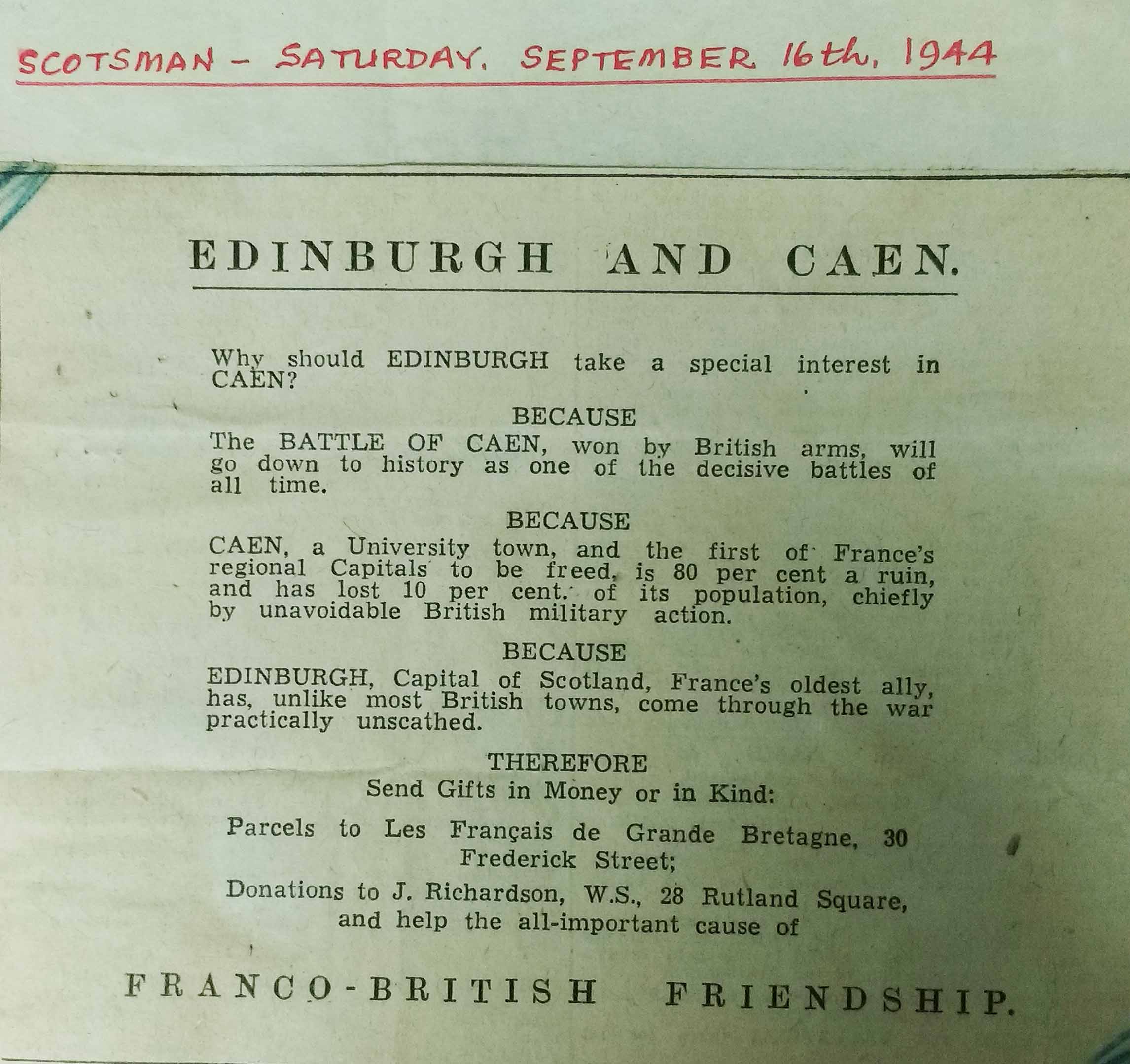

I started my little project on a sunny winter afternoon. Walking past my old university, I remembered that one of the nearby avenues was called ‘Avenue d’Edimbourg‘; and I finally understood why! Edinburgh was one of the cities that sent help and supplies to Caen after the bombing raid. The album is testimony to this connection: it was donated by John Orr, Professor of French at the University of Edinburgh and founder of the Caen-Edinburgh Fellowship. The latter was set up after the war to help the inhabitants of Caen by sending food, clothes, and supplies to the devastated city. John Orr himself organised for books to be sent to the library of the University, which was completely destroyed and had to be rebuilt from scratch, and for this he’s also had a street named after him.

Street signs named after John Orr.

Call for donations to Caen from the papers of Professor John Orr held in the Special Collections (Coll-77).

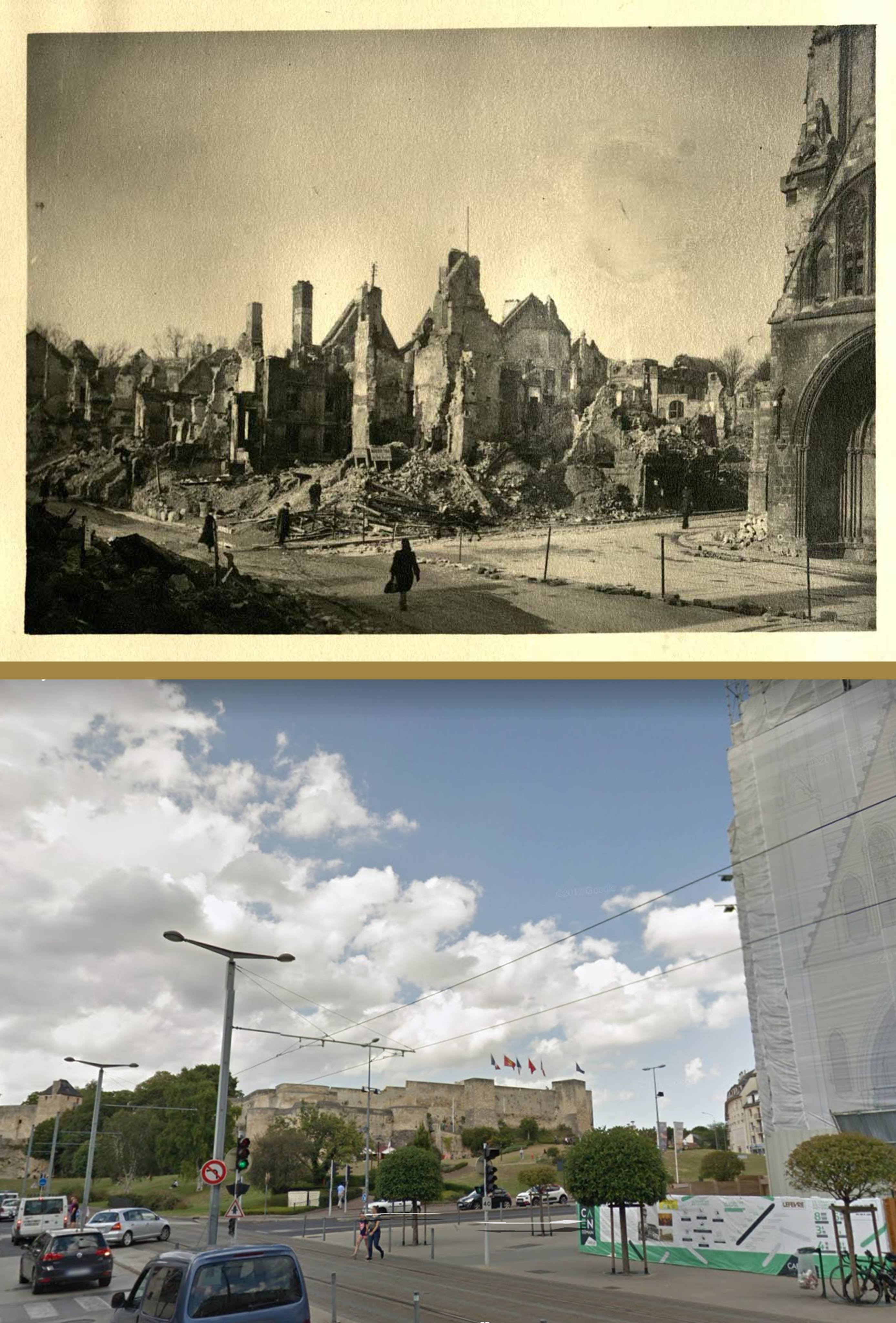

I soon arrived in the city centre. The most noticeable building in Caen is its massive castle, founded in 1060 by William the Conqueror. It was used as barracks between 1789 and 1945, and occupied by German troops during the War, which explains why it was targeted by bombings. Some buildings and parts of walls were damaged, but most of it survived in decent condition. The same cannot be said for the houses build alongside its walls…And so, after the clearing of the ruins, the castle reappeared, and it was decided to restore and showcase this millennium-old building that overlooks the city. The words of my grandmother came back to me: ‘We didn’t even know we had a castle because there were so many houses around it! After the war it came a bit as a surprise…’

Castle of Caen seen from St Pierre Church. The surrounding buildings which were hiding it for centuries were not rebuilt after the war. (Coll-164/61)

Maison des Quatrans. The buildings which were in-between the house and the castle have been destroyed. (Coll-164/71)

But not everything was completely destroyed in Caen! Our old town centre, the Quartier St-Pierre (‘St Pierre neighbourhood’), still has many original features. The Church, for starter – the tower was destroyed and then rebuilt, and is now being cleaned to restore its original white-yellowish colour, darkened by pollution. The buildings around it, however, went up in smoke. La Rue Montoire Poissonerie (Montoire Poissonerie Street), for example, has vanished.

St Pierre Church from Rue Montoire Poissonerie (now an apartment building). (Coll-164/11)

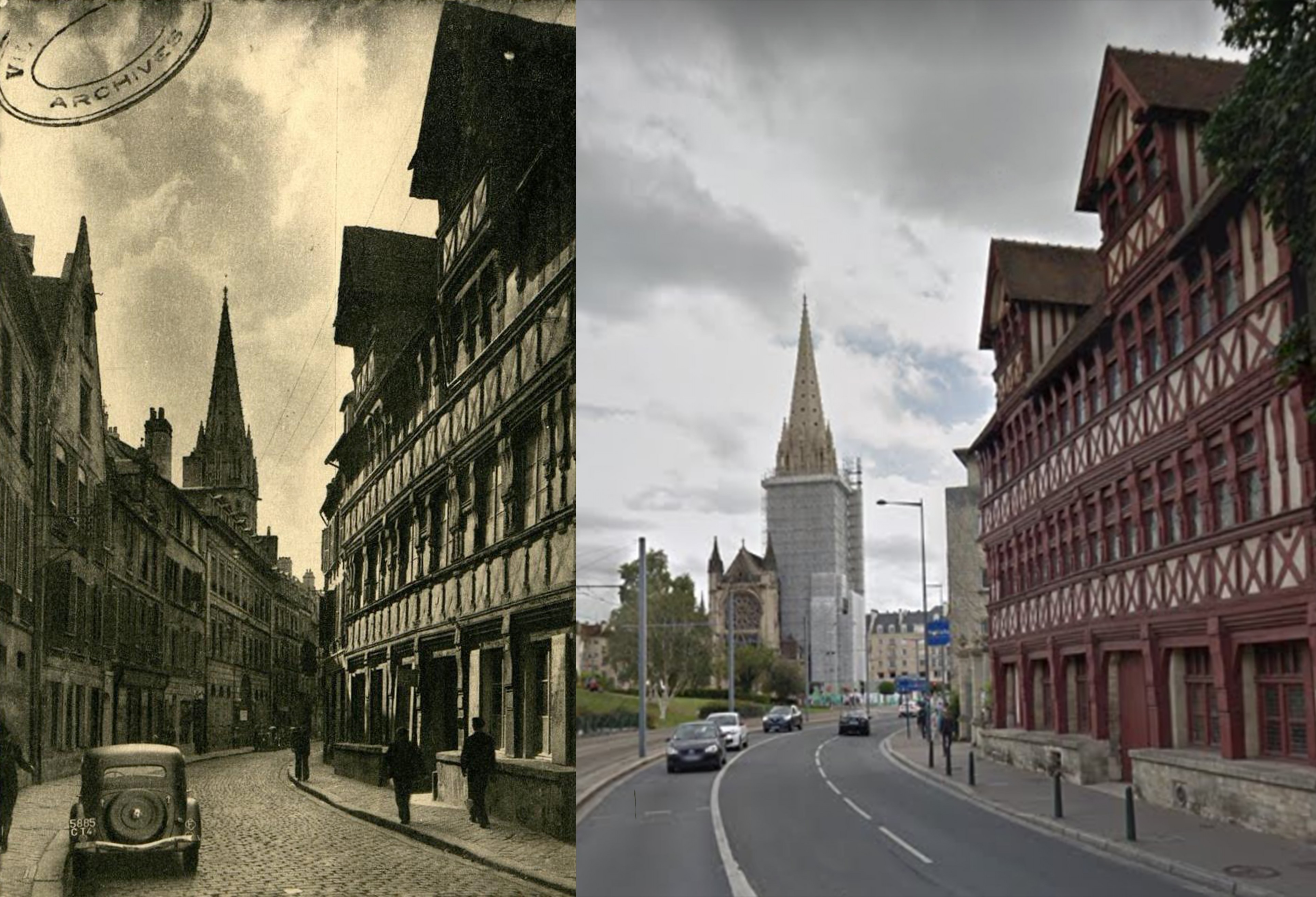

On the other hand, the main street of the neighbourhood, la rue St Pierre, has been more or less spared, and the old stands alongside the new. In the picture below you can see the busy Place St Pierre, full of shoppers and tourists, with the church Notre-Dame-de-Froide-Rue in the background and a beautiful half-timbered house from the 15th century. They miraculously survived, and are now being restored to get their lively colours back!

Place St Pierre and its 15th century half-timbered houses. (Coll-164/18)

Place St Pierre and Notre-Dame-de-Froide-Rue Church. (Coll-164/38)

As a medievalist, I still regret the loss of the Rue St Jean, a once beautiful street full of hôtels particuliers and ancient half-timbered houses just like the one in the picture above. One of the only original buildings still standing is the very curious Eglise Saint-Jean – which has the particularity of being completely wonky! Our very own modest Pisa Tower, which is leaning because Caen was built on unstable grounds. Everybody thought this fragile building would never last – little did they know it would be the only monument to survive the raid of St-Jean street.

Eglise Saint-Jean, which is much sturdier than it looks…(Coll-164/72)

Sometimes, there was nothing to save but a section of wall, a half-collapsed doorway, the base of a pillar…left as a memory, a reminder of what the city had gone through:

Saint-Gilles Church, now a small park. The only recognisable feature is an archway. (Coll-164/36)

Saint-Julien Church before, during and after the bombings. (Coll-164/45 and Coll-164/48)

Like many French towns and cities, old Caen was full of narrow, dark medieval streets that would add a lot of charm to a city nowadays. I remember lamenting about the destruction of these quaint quarters – some of the largest boulevards in Caen have actually been shaped by American bulldozers –, and my grandfather replying: ‘it was dark and dirty before, very cold and inconvenient. It’s nicer now. They did a good job rebuilding everything’. The inhabitants rebuilt their home with the very typical Caen stone, which has a light and warm yellow colour, and the new blends in with the old. The city may not be as beautiful as other French towns spared by the war, but it is a nice place to live, where history has left its mark.

Our archivist doing some fieldwork…

Description of the album on ArchivesSpace: https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/312

Aline Brodin, cataloguing archivist, 6 June 2018.

Special thanks to Clément Guézais and Inès Prat for their help in taking and editing the photographs.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....