Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

February 24, 2026

Data Carpentry Workshop, Spring 2018

Following on from the success of previous Carpentry workshops we have hosted, the Research Data Support team organised another two day Data Carpentry workshop on 12th /13th June 2018 in the David Hume Tower teaching studio.

Data Carpentry workshops focus on introductory computational skills needed for data management and analysis in all domains of research. If you have never heard of ‘Data Carpentry’, ‘Software Carpentry’ or ‘the Carpentries’ we suggest you go take a look around the Data Carpentry and Software Sustainability Institute websites. While the ‘Data Carpentries’ follow a similar theme, the lessons can vary between different workshops, depending on the level of the learners and their requirements. The topics covered were:

- Data Cleaning with OpenRefine

- Programming and Data Visualisation with R

- Relational DataBases and SQL

All the sessions received positive feedback from students on both content and delivery. The headliner for the workshop was undoubtedly the R programming: two R sessions delivered over Tuesday afternoon and Wednesday morning by the lead instructor Edward Wallace. Edward is based at King Buildings and uses R in his own research into RNA-protein interactions. He is clearly a great teacher as the feedback on these sessions indicated it was really well delivered and the pace of the course was just right. That is not easy to do when you have such a wide range of students from all disciplines.

This course was fully booked within a few hours of being advertised and there remained over 50 people registered on the waiting list indicating the demand for these data handling courses. The overwhelming feedback from the course was “more R training please!”. Keep a lookout for advertising on the RDS website and the university Events booking as more Carpentry training is on its way!

Thanks from the Research Data Support team to all the excellent helpers and trainers for making this event possible. All the trainers and helpers for this workshop were Edinburgh University staff.

Trainers: Edward Wallace, Giacomo Peru, Manos Farsarakis, Lucia Micheilin.

Helpers: Rosey Bayne, Sean McGeever, Mario Antonioletti, Daniel Robertson, Evgenij Belikov, Jennifer Daub.

This workshop was organised in collaboration by Research Data Service, EPCC, ARCHER and the Software Sustainability Institute.

Jennifer Daub

Research Data Support

Library & University Collections

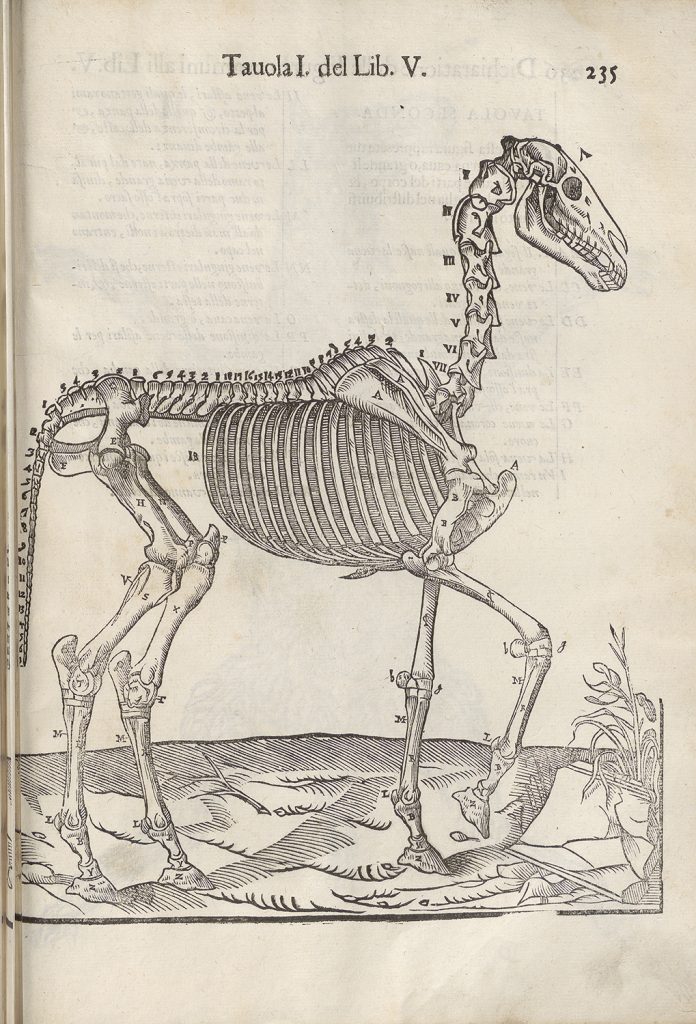

The Anatomy of the Horse

Recently I digitised Carlo Ruini’s ‘Anatomia Del Cavallo’ (The Anatomy of the Horse, Diseases and Treatments) as part of our Iconic’s collection on our i2S V-shape cradle scanner. It is a lavishly illustrated anatomic manual on the study of horses and was the first book to focus exclusively on the structure of a species other than man. In Ruini’s estimation, the horse combines ‘great love of man’ with natural docility and is celebrated for its many ways to bring pleasure and assistance to man that it is commemorated everywhere in monuments, tombs, poetry, and painting.

Completion of the Thomson-Walker Project

In this week’s blog our final Thomson-Walker Intern, Giulia, talks about the completion of the Thomson-Walker project and her experience of working at the CRC…

Giulia working in the studio

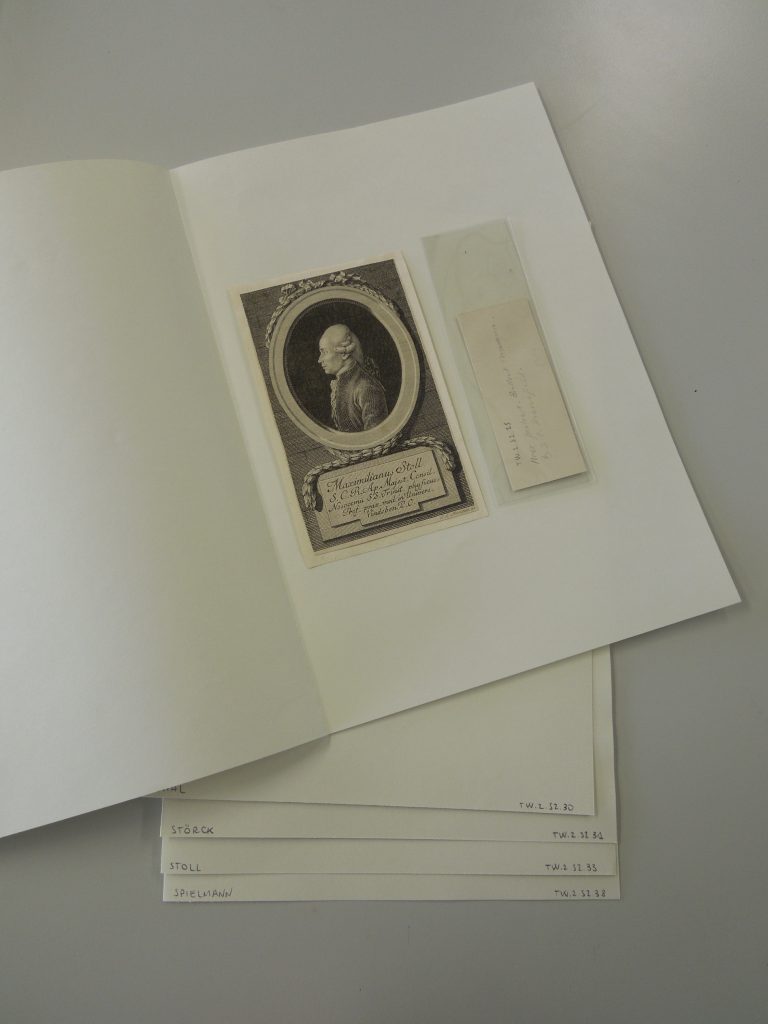

We did it! The conservation of the Thomson-Walker collection of medical portraits is finally complete! It took four years, five interns, dozens of batches of carboxymethylcellulose (CMC), several metres of lens tissue, and an indefinite number of acid-free paper sheets, but the 3,000 prints are finally free from acidic secondary supports, adhesive residues and tape hinges, and are now ready to be fully catalogued and digitized. At the beginning of my internship, I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to get through the final boxes in the collection. The previous interns’ fantastic work (you can read all about here, here, here and here) left me with 600 prints to conserve, from portraits classed under letter “P” to the ones under “Z”, with two jam-packed boxes labelled “S” in between. I really wanted to do my best to complete the project, since I was going to be the last intern to work on the Thomson-Walker collection, and also because I was determined to challenge myself, testing the workload I was able to carry out in a short period of time.

Print, after conservation, rehoused in a single crease acid-free folder

Scotland’s Languages: Changes and reasons

Here is the last in our series of posts on Scotland’s languages. This time we look more closely at why there were changes in the languages spoken in Scotland. As illustrated in the last two posts, it is inevitable for there to be changes in languages (vocabulary, pronunciation and intonation) and their use. As people are influenced by others from different parishes and even further afield, so their language reflects this. The single most important change to affect Scotland was the rise in the usage of the English language.

The rise of the English language

The English language was gaining ground by the end of the 18th century for a number of reasons:

- Ability to converse with people from other countries

- English was the language of trade

- English was the language of the higher ranks and well-educated

- English was increasingly being taught in schools and used in religious instruction

Here are some examples of what was written in parish reports on the use of English:

Alness, County of Ross and Cromarty – “The English, however, has made very considerable progress in the parish for 20 years back, owing to the benefit received from the number of schools planted in it much about that time.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 240)

Kirkhill, County of Inverness – “The language chiefly spoken by the common people is Gaelic; although a great many of them, from their being taught to read English at school, can transact ordinary business in that tongue.” (OSA, Vol. IV, 1792, p. 121)

Assynt, County of Sutherland – “The Gaelic language is still universal in Assynt, and the only medium of religious instruction. The English language, however, is making slow but sure progress. The youth of the parish are ambitious of acquiring it, being, sensible that the want of it proves a great bar to their advancement in life.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 112)

Aberdeen, County of Aberdeen – “The provincial dialect of the English, which is generally spoken here, is not commonly considered as being very pure. Owing, however, to a much greater intercourse with the English than formerly, a sensible change to the better has taken place in the idiom… The consideration also that this is a place of education; the seat of an university of considerable eminence; has proved an inducement to several, especially to those who have entertained thoughts of publishing in English, to make the proper idiom of the language more a matter of study than was ever done as any former period, a circumstance that has not failed to produce good effects.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 182)

Kilmorie, County of Bute – “yet persons advanced in years understand the English language tolerably; they acquire it by intercourse with other countries, and are greatly assisted by having the organs of speech formed in their youth, it being the first language they are taught to read.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 170)

Calder Mid, County of Edinburgh – “Though the Scotch be the prevailing language of the country, yet, by the influence of those who have a more extended intercourse with the world, the people here are making evident approaches toward a more intimate acquaintance with the English tongue, which is the more desirable, as, since the union of England and Scotland, the language of the court of London has been received as the standard language of the united kingdoms.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 365)

Dalmeny, County of Linlithgow – “The Dano-Saxon has continued to be spoken in the greater part of Scotland, and particularly what is called the Lowlands, with little deviation from the original, till near the present times, in which it has been giving place very rapidly to the modern English language. The cause of this, independent of the comparative merits or demerits of the two dialects, has been the union of the Scottish and English crowns; from which, as England is the larger and wealthier country, and is, besides, the court end of the Island, the English tongue has gained the ascendancy, and become the standard of fashion and of propriety.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 228)

Inverchaolain, County of Argyle – “Gaelic is the language of the natives, both old and young, but all of them can read and speak English. English is gaining ground, and all are anxious to acquire it.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 112)

As mentioned in an earlier post (Scotland’s languages: Gaelic, Scots and English), those parishes where English was gaining ground were not necessarily anywhere near the English border. This shows that trade and travel impacted on the language spoken. As can be observed in the excerpts above, education also had a massive impact on language use.

Education

More and more schools were teaching the English language at the time of the Statistical Accounts. In Tain, County of Ross and Cromarty, “the inhabitants of the town speak the English, and also the Gaelic or Erse. Both languages are preached in the church. Few of the older people, in the country part of the parish, understand the English language; but the children are now generally sent to school, and taught to read English.” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 393)

It was felt that knowing how to read and speak English would improve people’s lives, such as those in Jura, County of Argyle. “The language universally spoken in the parish is Gaelic. Very few of the old people understand English. But from the laudable endeavours of the schoolmasters to teach their scholars the vocabulary, and use of that language, and from a general opinion gaining ground, that it will be of great service in life, it is hoped that the rising generation will make considerable progress in acquiring the English language. The inhabitants do not feel that strong desire of bettering their circumstances, that would stimulate them to exertion and enterprize. Instead of trying the effects of industry at home, they foster the notion of getting at once into a state of ease and opulence, with their relations beyond the Atlantic.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p 322) (This last sentence is a very revealing one! See our previous post on emigration.)

In Kilmuir, County of Inverness, some very interesting reasons were given why children were being taught the English language first. “1st, The imitative powers of children, with respect to sounds and articulation, are more acute in early life than in maturer years; and were the Gaelic taught first, it would be almost impossible to adapt the tone of the voice afterwards to English pronunciation; 2dly, Although the English may take a longer period than the Gaelic to acquire it properly, yet, when it is acquired, the pupils can master the Gaelic without any assistance; and 3dly, Such as cannot speak the English, naturally are more reluctant to leave the country in quest of that employment which they cannot procure at home.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 281)

Some schools taught English as well as Gaelic, such as that of the parish of Gigha and Cara, County of Argyle (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 406). However, many parishes had more than one school, and it depended on which school you attended what language or languages you were taught. In Rogart, County of Sutherland, “there are three schools at present in operation in the parish,-the parochial school, a school supported by the General Assembly, and a Gaelic school, supported by the Gaelic School Society. In the parochial school, English reading, writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, mensuration, and land-surveying, are taught. In the General Assembly’s school, English reading, Gaelic reading, writing, arithmetic, and sometimes the rudiments of Latin, are taught. In the Gaelic school, the reading of the Gaelic only is taught.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 55)

There were five schools in the parish of Fodderty, County of Ross and Cromarty, each with a good number of attendees: “1. The parochial school, which has the maximum salary attached to it, exclusive of a dwelling-house,and L.2, 2s.in lieu of a garden. The branches taught are, English reading, grammar,writing, arithmetic, book-keeping, geography, Latin, and Greek. The average attendance is 63, and the annual amount of school fees paid may be about L. 16. 2. The school at Tollie, in the Brahan district, in connection with the Inverness Education Society. The attendance is 70. Both Gaelic and English are taught, together with writing and arithmetic. 3. The Gaelic school, supported by that excellent institution, the Gaelic School Society of Edinburgh, in which, old and young are taught to read the sacred Scriptures in their own language, and which is attended during winter by about 60. 4. The school at Maryburgh, on the scheme of the General Assembly’s Education Committee. The average attendance is 120. And, lastly, a school on the teacher’s own adventure, in the heights of Auchterneed ; at which the attendance is 84.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 259)

It wasn’t always in school where children learnt languages! In Balquhidder, County of Perth, “towards the end of Spring, most of the boys go to the low country, where they are employed in herding till the ensuing winter; and, besides gaining a small fee, they have the advantage of acquiring the English language.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 95)

The Gaelic School Society

As can be gleaned from above, the Gaelic School Society established many schools teaching Gaelic throughout Scotland. The society was set up in Edinburgh to primarily teach people to read the Scriptures in Gaelic. It, therefore, played a very important role in encouraging the use of the Gaelic language. (For more information see the 19th century section in the Wikipedia entry for Gaelic medium education in Scotland.) In Assynt, County of Sutherland, “it is likely, nevertheless, that Assynt is one of the very last districts in which the Gaelic language shall cease to be the language of the people. It is remarkable that the Gaelic School Society will probably prove the means, at a remote period, of the expulsions of the Gaelic language from the Highlands. The teachers employed by that useful society, to whom we owe much, taught the young to read the Scriptures in their native tongue. This implanted a desire to acquire knowledge on other subjects, which induced them to have recourse to the English language as the medium of communication.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 112)

Scripture extracts : for the use of the schools supported by the Gaelic School Society in the Highlands and Islands in Scotland. Published in Edinburgh for the Society in 1824. Digitized by The National Library of Scotland and accessed via the Internet Archive.

In some parishes, it was thanks to this Society that people could read at all. In the parish of Lochs, Ross and Cromarty, “there are only 12 persons in all the parish who can write; but half the inhabitants from twelve to twenty-four years of age can read the Gaelic language, which is the only language spoken generally. A few of the males can speak broken English. It was by the instrumentality of the Gaelic School Society that so many of them were enabled to read Gaelic. The Gaelic School Society has four schools at present in the parish of Lochs, which are the only schools in it.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 168)

Incidentally, it was claimed in the parish report of Killin, County of Perth, that “in the manse of Killin the present version of the Gaelic Scriptures was begun. The Gaelic Testament was executed by Mr James Stewart, from whom his son, the well-known Dr Stewart of Luss, obtained that knowledge of and taste for Gaelic literature which enabled him so faithfully to finish the Gaelic translation of the Bible. Killin may then fairly lay claim to the honour of this great work.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 1087)

However, not everyone in the county of Ross and Cromarty thought the Society so praiseworthy! In the parish report for Kiltearn, the Reverend Thomas Munro wrote the following: “The Gaelic School Society, by establishing schools throughout the country, have done much to eradicate the language. This may appear paradoxical; but it is actually the case. Those children that had learned to read Gaelic found no difficulty in mastering the English; and they had a strong inducement to do so, because they found in that language more information suited to their capacity and taste, than could be found in their own. English being the language universally spoken by the higher classes, the mass of the people attach a notion of superior refinement to the possession of it, which makes them strain every nerve to acquire it; and it is no uncommon thing for those who have lived for a short time in the south, to affect on their return, a total forgetfulness of the language which they had so long been in the habit of using.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 323)

You can read a fascinating article Gaelic School Society. Appeal to British Christians, Resident Abroad found in the Colonial Times, Tuesday, February 22, 1842, which is appealing to those living in Australia with Scottish connections to help the Society by giving donations or by subscribing to the Society.

The Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge

At the time of the Statistical Accounts of Scotland, there was also in existence the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge. This society established schools teaching the reading and writing of English and/or Gaelic, along with other common branches of instruction, such as arithmetic and knowledge of the Scriptures, such as the school established by the Society at Aberfoyle, County of Perth. (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 1158) In the Starthyre district of the parish of Balquhidder, County of Perth, “there is a school supported by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, in which are taught English, writing, arithmetic, and Gaelic.”(NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 348) In the parish of Urquhart and Glen, County of Inverness, “in the schools supported by the Society, great attention is paid to the teaching of the Gaelic language; and in the other schools, it is taught to those who wish to acquire it. (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 50)

As reported in the Appendix for Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh, “an hundred and sixty thousand children have been educated by this society, and there are ten thousand in their schools this year 1792.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 590) The quality of their schools was very important to the society, and they were not afraid to close schools down. For some reason, “the ambulatory school, once established in this parish [Small Isles, County of Inverness], by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, was removed in Summer 1792.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 290) Also, in the parish of Rathven, County of Banff, “the school in Buckie has been withdrawn by the Society, on the ground, that the school house has been allowed to fall into decay.” (NSA, Vol. XIII, 1845, p. 266)

In several parishes, such as that of Kincardine, County of Perth, applications were made to the society to establish much-needed schools. “Application having accordingly been made by the proprietor, the Society was pleased to enter very warmly into the situation of these poor people, and with the greatest alacrity agreed to the appointment of an experienced teacher, who was settled at Martinmas 1793. This teacher, who is well acquainted both with the Gaelic and the English languages, officiates through the week as schoolmaster, and on Sundays convenes the people in the schoolhouse, where be instructs them in the principles of religion, and says prayers to them in their native tongue.” (OSA, Vol. XXI, 1799, p. 181)

These applications show how important the society was to parishes throughout Scotland. Indeed, in Callander, County of Perth, you can find the following commendation: “Much praise is due to the excellent Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge; but for it, thousands in the Highland’s would have been deprived of the means of instructions. The people are alive to the benefit of education. All in this parish have the means of instruction, and all from six years and upwards can read. A very visible change in the conduct, morals, &c. of the people has taken place, since the facilities of education were increased.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 358). The Society even paid to inoculate the poor in the parish! (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 625)

Religion

The establishment of schools by both the Gaelic School Society and the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge illustrates the direct link which existed between education and religion at that time. Languages, whether the native-tongue or not, were being taught in order to enable people to read and learn from the Scriptures and the Shorter Catechism.

Of course, the most important consideration to parish ministers was what languages parishioners actually understood and used the most. Their needs and abilities had to be catered for. Here are some examples of having to find someone who could preach in Gaelic.

Cromarty, County of Ross and Cromarty – “There are two clergymen in the parish; the parish minister, and the minister of the Gaelic Chapel. There was no Gaelic preached in this place, until the erection of the chapel; and the principal reason of introducing it was, for the accommodation of Mr. Ross’s numerous labourers, and others who came from the neighbouring parishes to the manufacture of hemp.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 256)

Crathie, County of Aberdeen – “There is missionary minister, paid by the Royal Bounty, stationed in Braemar; but as he has not the Gaelic language, and as there are some persons who do not understand any English, the parish minister is obliged to exchange pulpits with him very frequently. The General Assembly of the church of Scotland have now pledged themselves, that how soon the present missionary is otherwise provided for, they shall appoint one for the future to that mission, but persons having the Gaelic language.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 344)

Ardersier Parish Church, near Inverness. Photograph taken by Dave Connor, 2015. Via Flickr under Creative Commons License 2.0. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Ardersier, County of Inverness – “It is a curious circumstance that, from the year 1757 to 1781, during the ministrations of two incumbents, no Gaelic was preached in the parish. On the ordination of the Rev. P. Campbell, in the latter year, it was requested by the peoples, and agreed to by him, that be should exhort them in the Gaelic language.” (NSA, Vol. XIV, 1845, p. 472)

However, as previously mentioned, English was becoming more widespread. Therefore, the availability of religious instruction in English was also increasing. In Dunoon and Kilmun, County of Argyle, “the language of the parish is changing much, from the coming in of low-country tenants, from the constant intercourse our people have with their neighbours, but above all, from our schools, particularly, those established by the Society for propagating Christian Knowledge. Hence the English or Scottish language is universally spoke by almost all ages, and sexes. But the Gaelic is still the natural tongue with them, their fireside language, and the language of their devotions. They now begin, however, to attend public worship in English as well as Erse, which 30 years ago they did not do.” (OSA, Vol. II, 1792, p. 389)

As reported in the parish of Aberfoyle, County of Perth, “in ancient times, the Gaelic language alone was spoken in this parish; and, even in the memory of man, it extended many miles farther down the country than it now does. The limits of this ancient tongue, however, are daily narrowed here as every where else, by the increasing intercourse with the low country. At present, every body understands English, though the Gaelic is chiefly in use. The service in church is performed in English in the forenoon, and in Gaelic in the afternoon.” (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 129)

There are some very interesting observations made in the parish report for Torosay, County of Argyle, on languages, education and religious instruction. “So far, therefore, as they [the natives] are concerned, the language [Gaelic] has neither gained nor lost ground, for the last forty years. How long it may remain in this stationary condition is uncertain, especially as there are several families from the lowlands of late settled in the parish. These, having no inducement to study the Gaelic, as they find themselves generally understood in English, may, through time, habituate the natives to speak this language, even among themselves. At school, children are taught to read in both languages. Though the teaching of them thus to read Gaelic would seem to tend to its permanency, the contrary effect, in all probability, will ensue. By being able to compare both versions of the Scriptures, they daily add to their vocabulary of English words, so that the Gaelic in this manner forms to them a key for the acquisition of the English. So long as the native Highlanders understand Gaelic better than English, religious instruction must be communicated to them in that language, even if this circumstance should have the effect of postponing the day when English shall be the universal language of the empire. For, however desirable that event may be, it would be making too great a sacrifice to attempt to expedite it by suffering, in the meantime, even one soul to perish for lack of that knowledge which maketh wise unto salvation.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 289)

Resistance to change

Even though all these changes were taking place in schools and churches throughout Scotland, it must be noted that there was some resistance to the increasing use of English. Gaelic was still the preferred language in some quarters. In Urray, County of Ross and Cromarty,”Gaelic is the vernacular language of the whole parish, except in gentlemen’s families. Several of the inhabitants read the English Bible, and can transact business in that language; but they, as well as the bulk of the people, prefer religious instruction in Gaelic; and therefore are at pains to read the Gaelic New Testament, and Psalm Book, etc.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 259)

Both the Gaelic and Scotch languages were seen as noble and expressive languages. In Callander, County of Perth, “the language spoken by persons of rank and of liberal education, is English; but the language of the lower classes is Gaelic. It would be almost unnecessary to say anything of this language to those who understand it. They know its energy and power; the ease with which it is compounded; the boldness of its figures; its majesty, in addressing the Deity; and its tenderness in expressing the finest feelings of the human heart. But its genius and constitution, the structure of its nouns and verbs, and the affinity it has to some other languages, are not so much attended to. These point at a very remote area, and would seem to deduce the origin of this language from a very high antiquity.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 611) In Dalziel, County of Lanark, “the language generally spoken is a mixture of Scotch and English. The use of the Scotch has decreased within the last forty years, in consequence, I apprehend, of the improvement in teaching at the schools. But when persons are under excitement, the language used is Scotch. Then, the writer has observed, here and in other parts of Scotland, that the lower orders of society and many in the middling ranks, too, discover an acquaintance with that expressive dialect, which could not be inferred from their ordinary conversation.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 454) The native tongue is an integral part of the heritage and history of the people in the locality; its influence cannot be easily diminished, as the two examples above illustrate.

Conclusion

Looking at the Statistical Accounts of Scotland, one can identify several influences on the use of language, and English in particular, most notably travel, trade and education. What is really interesting is how these factors were interrelated. A knowledge of English allowed people to converse with people from the low countries and beyond. This then enabled greater trade, which allowed people to gain influence. The English language became the language of opportunities, so was increasingly being taught in schools. In turn, changes in education affected what was being used in everyday life and had a direct bearing on the language of people’s devotions, i.e. what was read and spoken in religious contexts.

______________________________________

It has been really fascinating to look at language use as a whole in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland, from place names through to the factors impacting on the languages spoken in Scotland. The country’s geography, history and culture have all played their part in shaping its linguistic landscape, making it what it is today. It is hoped that these series of posts will encourage you to further explore Scotland’s languages in the Statistical Accounts. If you find something particularly interesting let us know!

New to the Library: The SHAFR Guide Online

Thanks to a request from staff in HCA the Library now has access to The SHAFR Guide Online: An Annotated Bibliography of U.S. Foreign Relations since 1600. This is a near-comprehensive, 2.1 million-word online annotated bibliography of historical work covering the entire span of U.S. foreign relations.

You can access The SHAFR Guide Online via the Databases A-Z list, History database list and other relevant subject database lists. You’ll soon also be able to access it via DiscoverEd.

The SHAFR Guide Online covers all eras in U.S. history from colonial days onwards.

It also includes four new thematic chapters—on economic issues; non-governmental actors; domestic issues, the Congress, and public opinion; and race, gender, and culture.

Created by the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR), entries in the guide are drawn from many sources, from collections of government documents to biographies, monographs, book chapters, journal articles, web sites, and more.

Access The SHAFR Guide Online via the Databases A-Z list, History database list and other relevant subject database lists.

Access is only available to current students and staff at the University of Edinburgh.

Caroline Stirling – Academic Support Librarian for History, Classics and Archaeology

New to the Library: The Listener Historical Archive

I’m happy to let you know that after a successful trial earlier this year the Library now has access to The Listener Historical Archive, 1929-1991 from Gale Cengage. This gives you complete access to the archive of this landmark BBC publication.

You can access The Listener Historical Archive, 1929-1991 via the Databases A-Z list and Newspapers & Magazines database list. You can also access the title through DiscoverEd.

Screenshot from front page of first issue, Wednesday, January 16, 1929.

NHS at 70: Explore the history of the NHS through our primary sources

70 years ago today, 5 July, the National Health Service (NHS) was established, one of a number of social and welfare reforms from the post-World War II Labour government (though initial proposals for the NHS came from the World War II coalition government). Launched just over two years after Aneurin Bevan, Minister of Health, published his National Health Service Bill, the NHS provided medical and healthcare services for free at the point of delivery.

On the NHS’s 70th birthday I have pulled together a small selection of primary resources, digital and physical, you have access to at the Library that will help you explore the history of the NHS.

What did the people think?

Mass Observation was a pioneering social research organisation founded in 1937. The aim was to create an ‘anthropology of ourselves’, and by recruiting a team of observers and a panel of volunteer writers they studied the everyday lives of ordinary people in Britain. This original work continued until the early 1950s and gives unparalleled insight into everyday life in Britain during that time.

Through our Library you have access to Mass Observation Online, which makes available the entire Mass Observation archive from that period and includes original manuscript and typescript papers (such as diaries, day reports, questionnaires, observations, etc.) created and collected by the Mass Observation organisation, as well as printed publications, photographs and some interactive features.

Mass-Observation. 1949. Meet Yourself at the Doctor’s. London: Naldrett. Available from Mass Observation Online.

In Mass Observation Online you will find a large amount of material detailing people’s opinions and experiences of the NHS from its earliest days. From Mass Observation’s own file reports and publications pulling together people’s comments, observations and experiences of the NHS to the original diary entries and questionnaire responses.

The material available allows you to read about people’s views on the NHS prior to it being launched and their opinions and experiences of the service in its first few years of existence.

When you are using Mass Observation Online the easiest way to find material regarding the NHS is by clicking on the “Popular Searches” button near the top right-hand side of page and then under the “Organisations” tab click on “National Health Service”. Read More

A Prized Collection

We were recently rather excited to receive a significant accrual to an existing donation of records from Scottish Gymnastics. This includes over 100 books (some of them rare and inscribed), papers and photographs and an extensive collection of shields, trophies, medals, and other artefacts. A donation of objects like these in such a quantity is quite unusual for us and they make up by far the largest part of the Scottish Gymnastics archive. However the proportion of objects to paper records makes complete sense in the context of the organisation’s chief focus on local, national and international competitions.

The collection comprises a real mix of objects, including medals, shields, trophies and plaques, dating from the 1890s (when the organisation was new) right up to 2017. As well as objects which were given as awards, the collection also includes commemorative objects, particularly glassware, which were given to Scottish Gymnastics to mark their participation in particular events over the years.

Probably the most historically notable item in the collection is the Scottish Shield, an impressively decorated three-foot wide object bearing the Scottish Gymnastics logo and the names of the previous winners (picture below):

The shield was awarded as part of an annual competition between Scottish gymnastics clubs. The first winners, in 1890, were the Aberdeen Gymnastic and Rowing Club (the oldest of the Scottish gymnastics clubs). Jim Prestidge’s invaluable book The History of British Gymnastics also features this photograph of the shield in 1902, when it was won by the Dundee Gymnastic and Athletic Club (shield is on the far left).

At the time Prestidge was writing (1988), the Scottish Shield was still being awarded, and Prestidge states that it “is the longest serving Team Shield still in service”. It must certainly be one of the oldest gymnastics awards in Scotland, predating the famous Adams Shield (also featured in the above photograph, on the right) by nine years. We would like to find out more about the history of the Scottish Shield, so please do let us know if you have any information to share!

Artefacts like these form an important part of sporting heritage collections, but because of their unwieldy nature, they are often at risk of being discarded or forgotten, with institutions sometimes being reluctant to take them in. So it’s fantastic to now have this very tangible – and often downright beautiful – part of gymnastics history here at the Centre for Research Collections. The items are a valuable resource for understanding the material culture of gymnastics as well as giving precise information about individual, team and club achievements over time. It would be great to now see researchers begin to use this collection to its full potential.

The Scottish Gymnastics archives catalogue is currently being updated to include these new items. Once this is complete, the catalogue will be viewable here:

http://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/86677

Clare Button

Project Archivist

Sources

Prestidge, Jim, The History of British Gymnastics (British Amateur Gymnastics Association, 1988)

New to the Library: New York Amsterdam News

I’m delighted to let you know that following a successful trial in 2017/18 the Library has now purchased access to the New York Amsterdam News (1922-1993) from ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Founded in 1909 this is one of the leading Black newspapers of the 20th century and the oldest and largest Black newspaper in New York City.

You can access New York Amsterdam News (1922-1993) via the Databases A-Z list and Newspapers & Magazines database list. You can also access the title through DiscoverEd*

The Amsterdam News was founded over 100 years ago by James H. Anderson and was named after the street where he lived and where the first issues were produced and sold. It was one of only 50 Black newspapers in the United States at that time. Read More

New! News, Policy & Politics Magazine Archive

I’m happy to let you know that following some successful trials in the last couple of years the Library has purchased the News, Policy & Politics Magazine Archive from ProQuest. This resource offers digital access to the archival runs of 15 major 20th and 21st century consumer magazines covering such fields as the history of politics, current events, public policy and international relations. Central to this collection is the archive of Newsweek, one of the 20th century’s most prominent and highest circulating general interest magazine.

You can access News, Policy & Politics Magazine Archive from the Databases A-Z list and appropriate databases by subject lists. You’ll soon be able to access it from DiscoverEd as well. Read More

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....