Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 13, 2025

Revealing and Expanding Diversity in our Library Collections: Black History Month 2018

It’s Black History Month, and to celebrate diversity in the University’s collections we now have a new book display in the Main Library foyer. This follows on from the success of our Black History Month ‘micro-exhibition’ with EUSA last year.

Our latest display is part of a project where the Library is working with EUSA to reveal, and further expand, the diverse collections which the Library holds. This month, we have a selection of texts on display, from works by Chinua Achebe to Zadie Smith, and a number of new purchases for the Library’s collections.

We also have a resource list, detailing many of the items on display:

Black History Month 2018 resource list

Head down to the Main Library from 8-19 October to browse and borrow!

New electronic resource trial: Artfilms-Digital

Artfilms-Digital is the video streaming service of Contemporary Arts Media and Artfilms and provides access to over 1660 videos in Arts & Humanities subject areas with strengths in performing arts, visual and digital art, architecture, design, new media, film, cinema, communication and culture. Includes masterclasses, documentaries, and interviews. Read More

Greater Expectations? Writing and supporting Data Management Plans

“A blueprint for what you’re going to do”

This series of videos was arranged before I joined the Research Data Service team, otherwise I’d no doubt have had plenty to say myself on a range of data-related topics! But the release today of this video – “How making a Data Management Plan can help you” – provides an opportunity to offer a few thoughts and reflections on the purpose and benefits of data management planning (DMP), along with the support that we offer here at Edinburgh.

“Win that funding”

We have started to hear anecdotal tales of projects being denied funding due – in part at least – to inadequate or inappropriate data management plans. While these stories remain relatively rare, the direction of travel is clear: we are moving towards greater expectations, more scrutiny, and ultimately into the risk of incurring sanctions for failure to manage and share data in line with funder policies and community standards: as Niamh Moore puts it, various stakeholders are paying “much more attention to data management”. From the researcher’s point of view this ‘new normal’ is a significant change, requiring a transition that we should not underestimate. The Research Data Service exists to support researchers in normalising research data management (RDM) and embedding it as a core scholarly norm and competency, developing skills and awareness and building broader comfort zones, helping them adjust to these new expectations.

“Put the time in…”

My colleague Robin Rice mentions the various types of data management planning support available to Edinburgh’s research community, citing the online self-directed MANTRA training module, our tailored version of the DCC’s DMPonline tool, and bespoke support from experienced staff. Each of these requires an investment of time. MANTRA requires the researcher to take time to work through it, and took the team a considerable amount of time to produce in order to provide the researcher with a concise and yet wide-ranging grounding in the major constituent strands of RDM. DMPonline took hundreds and probably thousands of hours of developer time and input from a broad range of stakeholders to reach its current levels of stability and maturity and esteem. This investment has resulted in a tool that makes the process of creating a data management plan much more straightforward for researchers. PhD student Lis is quick to note the direct support that she was able to draw upon from the Research Data Service staff at the University, citing quick response times, fluent communication, and ongoing support as the plan evolves and responds to change. Each of these are examples of spending time to save time, not quite Dusty Springfield’s “taking time to make time”, but not a million miles away.

There is a cost to all of this, of course, and we should be under no illusions that we are fortunate at the University of Edinburgh to be in a position to provide and make use of this level of tailored service, and we are working towards a goal of RDM related costs being stably funded to the greatest degree possible, through a combination of project funding and sustained core budget.

“You may not have thought of everything”

Plans are not set in stone. They can, and indeed should, be kept updated in order to reflect reality, and the Horizon 2020 guidelines state that DMPs should be updated “as the implementation of the project progresses and when significant changes occur”, e.g. new data; changes in consortium policies (e.g. new innovation potential, decision to file for a patent); changes in consortium composition and external factors (such as new consortium members joining or old members leaving).

Essentially, data management planning provides a framework for thinking things through (Niamh uses the term “a series of prompts”, and Lis “a structure”. As Robin says, you won’t necessarily think of everything beforehand – a plan is a living document which will change over time – but the important things is to document and explain the decisions that are taken in order for others (and your future self is among these others!) to understand your work. A good approach that I’ve seen first-hand while reviewing DMPs for the European Commission is to leave place markers to identify deferred decisions, so that these details are not forgotten about (This is also a good reason for using a template – a empty heading means an issue that has not yet been addressed, whereas it’s deceptively easy to read free text DMPs and get the sense that everything is in good shape, only to find on more rigorous inspection that important information is missing, or that some responses are ambiguous.)

“Cutting and pasting”

It has often been said that plans are less important than the process of planning, and I’ve been historically resistant to sharing plans for “benchmarking” which is often just another word for copying. However Robin is right to point out that there are some circumstances where copying and pasting boilerplate text makes sense, for example when referring to standard processes or services, where it makes no sense – and indeed can in some cases be unnecessarily risky – to duplicate effort or reinvent the wheel. That said, I would still generally urge researchers to resist the temptation to do too much benchmarking. By all means use standards and cite norms, but also think things through for yourself (and in conjunction with your colleagues, project partners, support staff and other stakeholders etc) – and take time to communicate with your contemporaries and the future via your data management plan… or record?

“The structure and everything”

Because data management plans are increasingly seen as part of the broader scholarly record, it’s worth concluding with some thoughts on how all of this hangs together. Just as Open Science depends on a variety of Open Things, including publications, data and code, the documentation that enables us to understand it also has multiple strands. Robin talks about the relationship between data management and consent, and as a reviewer it is certainly reassuring to see sample consent agreement forms when assessing data management plans, but other plans and records are also relevant, such as Data Protection Impact Assessments, Software Management Plans and other outputs management processes and products. Ultimately the ideal (and perhaps idealistic) picture is of an interlinked, robust, holistic and transparent record documenting and evidencing all aspects of the research process, explaining rights and supporting re-use, all in the overall service of long-lasting, demonstrably rigorous, highest-quality scholarship.

—

Martin Donnelly

Research Data Support Manager

Library and University Collections

University of Edinburgh

New! Royal Society of Chemistry E-Books 2018

The Library has purchased the 2018 copyright year of Royal Society of Chemistry e-books. The first batch of titles have now been added to DiscoverEd. (50 titles).

The Library has purchased the 2018 copyright year of Royal Society of Chemistry e-books. The first batch of titles have now been added to DiscoverEd. (50 titles).

A title list can be viewed at http://pubs.rsc.org/en/ebooks#!key=copyright-year&value=2018

‘Moving forwards towards perfection’: Dunfermline College of Physical Education

Dunfermline College, original building. Part of the Records of Dunfermline College of Physical Education (EUA IN16)

On this day (4th October) in 1905, the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust College of Hygiene and Physical Training (later renamed Dunfermline College of Physical Education) was founded. It was opened by the Marquis of Linlithgow (who was Secretary for Scotland) in the ‘palatial’ Carnegie Gymnasium in the presence of over 1,000 people. The ceremony was an important milestone in the history of the town of Dunfermline but also Scotland as a whole; this was the first college of physical education of its kind in the country.

Dunfermline had already been home to a number of health-focused amenities, thanks to funding from its native son, the Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. There was ‘The Carnegie Gymnastics Club’ for young men and, later, a new gymnasium, swimming baths and Turkish Baths on Pilmuir Street.

The Carnegie Baths. Part of Records of Dunfermline College of Physical Education (EUA IN16)

Turkish Baths, Dunfermline. Part of the Records of Dunfermline College of Physical Education (EUA IN16)

The idea of public health and fitness was a growing concern following the publication of the Report of the Royal Commission on Physical Training (Scotland) a year earlier. With widespread poverty and malnutrition, cramped, urban lifestyles and a lack of physical education in schools, the fitness of the general population was found to be severely lacking. The Report effectively recommended compulsory physical education in schools to help combat this.

A syllabus of physical exercises was published for use in public elementary schools and the Carnegie Dunfermline Trustees provided male and female teachers to visit schools weekly and instruct children. However, there was a shortage of teachers specially trained in physical instruction and it was decided that a training college should be formed.

Miss Flora Ogston (daughter of Sir Alexander Ogston, Regius Professor of Surgery, University of Aberdeen from 1882 to 1909) became the first Principal of the College, which accepted women students only. Teaching at the College focused on theoretical and practical aspects of physical education, and included human anatomy and physiology, Ling’s Swedish system of gymnastics, remedial massage and, perhaps surprisingly, singing and voice production. The first 11 students to complete the two-year diploma course did so in 1907.

College Hockey Team, 1905-1906. Part of the Records of Dunfermline College of Physical Education (EUA IN16)

Giving a toast to the College at a dinner following the opening ceremony, Alexander Ogston concluded with his vision of what it represented in terms of national achievement and improved human wellbeing:

Scotland does not stand where it did; where formerly it was covered with what were quaintly termed “foul moors,” it is now so altered that it presents in their stead scenes of charming beauty and fertility, or is filled with the evidence of man’s industry and genius. It is not too much to expect that the agencies now active in the amelioration of the physical condition of its people, among which we hope the Dunfermline College will play a great part, will result in a somewhat similar elevation of all its inhabitants, in the production of a higher, nobler, better race, moving forwards towards perfection.

The records of Dunfermline College of Physical Education are currently being catalogued and we look forward to sharing more stories from the archive soon!

Sources:

- Addresses delivered on the occasion of the inauguration of the Carnegie Dunfermline Trust College of Hygiene and Physical Training on the 4th October 1905 (Dunfermline: A. Romanes & Son, 1905)

- Dr I.C. MacLean, The History of Dunfermline College of Physical Education (Edinburgh: Dunfermline College of Physical Education, 1976)

- www.victorianturkishbath.org

Clare Button

Project Archivist

Battle of Cable Street: through our newspaper archives

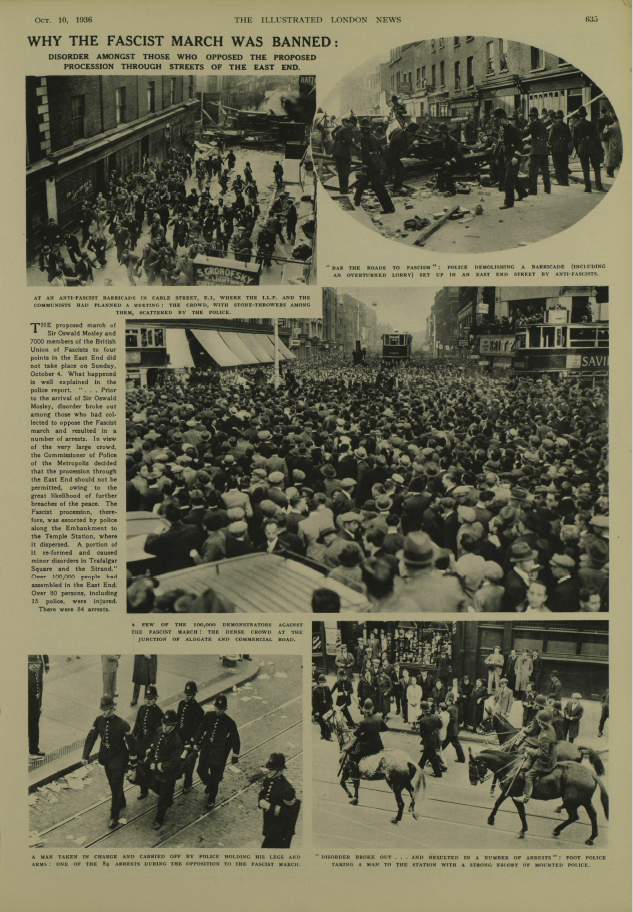

On this day, 4th October, in 1936 large crowds of people gathered in London’s East End, an area of the city that had a large Jewish population, in an attempt to stop a march through the area by the British Union of Fascists (BUF). The protests turned into a riot with anti-fascist demonstrators clashing with Police, large numbers of demonstrators were arrested and even larger numbers of them (and Police) were injured. But they did manage to prevent the march from taking place.

In this week’s blog post I’m using some of the Library’s digital newspaper databases to find primary source material about the Battle of Cable Street (as the demonstrations became known).

Screenshot from Illustrated London News, October 10, 1936, p. 635. From The Illustrated London News Historical Archive.

1893: A story of scary librarians and brave students

Student helpers at New College Library 1893 ( from the New College Library Archives AA 1.8.1)

New College Library and its students have always had a special relationship. Recently, for example, our students chose their preferred most iconic items from our special collections and contributed to our beautiful exhibition ‘Steps through Time’ (you can check the corresponding post here).

However, not everyone knows that from the early stages of New College Library’s existence, students have played a fundamental role in the organisation and establishment of the library. For example, in 1843, when New College was founded, it was ‘student curators’ who stamped and listed the first donations that arrived at the library from various sources (see Disruption to Diversity, D.Wright and G.D.Badcock, p.187).

In spite of their initial involvement though, in its early days browsing New College Library was not a particularly student friendly experience. In fact, until 1893, the library was entirely the domain of the Librarian – he was the only one who had an overview of the entirety of the catalogue and the only one who was able to peruse the shelves and collect the books requested by the students.

Not only were students not allowed to browse the shelves freely, they were also kept in relative ignorance of the contents of the library, especially if some of the books did not meet with the Librarian’s criteria of safe readings. For example, Dr Kennedy, who was the Librarian of New College Library from 1880 until 1922, ‘even adopted the stratagem of frustrating any reader, privileged to inspect the shelves, who sought to escape his lynx-like vigilance, by secreting scores of “dangerous” volumes on shelves hidden behind tables or forms ’, as Hugh Watt writes in New College a centenary history (p.162). The catalogue was also a fairly complicated affair, since for several years it consisted of written slips kept in packages accessible only to the Librarian.

Unsurprisingly, this was a most unsatisfactory system for the poor students. Therefore, in 1892, six students braved the phenomenal Dr Kennedy, and under his ‘lynx-like’ vigilance, they assisted him in re-arranging the catalogue to make it more user accessible. After a year of hard work, they published what you can consider as one of DiscoverEd’s ancestors: The Abridged Catalogue of Books in New College library, Edinburgh,1893.

And here, from the depths of New College Library’s Archive collection, is the picture of our student heroes:

New College Library Archives (AA.1.8.1)

And here, with a well-deserved drink after a year of work with the impressive Dr Kennedy:

New College Library Archives (AA 1.8.1.)

While we are not encouraging you to drink beer in the library, or to rebel against our lovely library staff (nowadays, certainly not as scary as good, old Dr Kennedy), we want to celebrate those students with you today. It was also thanks to their hard work that New College Library became the much loved library that it is today.

Not much is known about those student heroes, their names are faded, a scribble at the back of an old photograph. But perhaps next time you wander through the library, send them a grateful thought. They will surely appreciate it.

Barbara Tesio, IS Helpdesk Assistant, New College Library

Research Data Service use cases – videos and more

Earlier this year, the Research Data Service team set out to interview some of our users to learn about how they manage their data, the challenges they face, and what they’d like to see from our service. We engaged a PhD student, Clarissa, who successfully carried out this survey and compiled use cases from the responses. We also engaged the University of Edinburgh Communications team to film and edit some of the user interviews in order to produce educational and promotional videos. We are now delighted to launch the first of these videos here.

In this case study video, Dr Bert Remijsen speaks about his successful experience archiving and sharing his Linguistics research data through Edinburgh DataShare, and seeing people from all corners of the world making use of the data in “unforeseeable” ways.

Over the coming weeks we will release the written case studies for internal users, and we will make the other videos also available on Media Hopper and YouTube. These will address topics including data management planning, archiving and sharing data, and adapting practices around personal data for GDPR compliance and training in Research Data Management. Staff and users will talk about the guidance and solutions provided by the Research Data Service for openly sharing data – and conversely restricting access to sensitive data – as well as supporting researchers in producing meaningful and useful Data Management Plans.

The team is also continuing to analyse the valuable input from our participants, and we are working towards implementing some of the helpful ideas they have kindly contributed.

Women in Scotland: Women in work

In the last three of posts on women in Scotland we have discovered that women worked in many sectors, including manufacturing (spinning, weaving, needlework,etc), and the farming and fishing industries. In this post we look more generally at the impact society had on women and their work.

Multi-tasking!

In many instances, women had to work as well as look after the family – as they do now! In Northmaving, County of Shetland, “the women look after domestic concerns, bring up their children, cook the victuals, look after the cattle, spin, and knit stockings; they also assist, and are no less laborious then the men in manuring and labouring the grounds, reaping the harvest, and manufacturing their crop.” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 358) They also undertook not just one type of work, but several, depending on the time of year and the wages they received. In Nigg, County of Kincardine, “the whole female part of the parish, when not occupied by these engagements [kelp production], or harvest, the most, and domestic affairs, work at knitting woolen stockings, the materials of which they generally receive from manufacturers in Aberdeen.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 207) In Clackmannan, County of Clackmannan, “during a considerable part of the year, some of the women in the parish continue to sew for the Glasgow manufacturers, but the earnings from this source are now most lamentably small. Most of the females to which the writer has been referring, derive the greater part of their annual subsistence from field-labour, the preparing of bark, &c.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 129)

No time for housework!

Although women had to multi-task, it was sometimes remarked in the parish reports that, due to women working, the state of the home suffered! Here is what was written in the parish report of Cross and Burness, County of Orkney:

“But there is a great want of neatness and cleanliness in the management of household matters, so that their condition has nothing of the tidy and comfortable appearance of what is now to be met with in houses of a like description in the south. And for any effectual improvement in this respect, there are two formidable barriers in the way, which are not likely soon to be overcome. The women have much work to do out of doors, a species of work, too, which peculiarly unfits them for neat management of house-hold concerns, such as cutting sea-weed for kelp, carrying up ware for manure on their backs, and spreading it on the land; and besides, the construction of their houses is very unfavourable, which are not only not plastered but not even built with lime, and seldom have any semblance of a chimney even upon the roof, while, for the sake of having each part of the house supplied with an equal share of heat, the fire-place is most commonly planted in the middle of the floor. The smoke consequently finds its way in every direction, and to keep either the walls or the utensils in a state of proper cleanliness, is next to impossible. Yet the present form of houses is much superior to what was possessed by the last generation; and this form may soon perhaps give way to another in a higher state of improvement.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 106)

In the parish report for Carmylie, County of Forfar, it was noted that weaving, the new type of employment for young women at that time, “forms no good training for their management of household affairs” in the event of them getting married. (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 371) It was an even worse situation for colliers families in Tranent, County of Haddington! “The injurious practice of women working in the pits as bearers (now happily on the decline with the married females), tends to render the houses of colliers most uncomfortable on their return from their labours, and to foster many evils which a neat cleanly home would go far to lessen.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 295). However, spinning, in particular, was considered a job which married women could do and still be able to run a household, as alluded to in the parish report for Moulin, County of Perth. (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 63)

The need for women (and children) to work

In several parishes it was noted that there were many more females than males residing there, mostly due to men working elsewhere, particularly in the army or navy. This obviously had an effect on who undertook the work in that parish. In Stenton, County of Haddington, “the disparity in the number of males and females probably arises from a number of young men leaving the parish in search of employment; and the young women remaining as outworkers, in which occupation a good many single women, householders, are employed, who receive 9d. every day they are called upon to work, with 600 yards of potatoes planted, coals driven, &c. for their yearly service.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 58) Whereas, in Rathven, County of Banff, the disparity between males and females residing there was attributed to losses sustained at sea and an influx of poor women from the Highlands, who wanted to live more comfortably. (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 417)

It was noted in the parish report of Nigg, County of Kincardine, that “during some later months of winter, the subsistence of the family has depended much on the work of the females. Since the commencement of the American and French war 1778, 24 men have been impressed or entered to serve their country in the fleet from the fisher families. In these late armaments, their fishing has been interrupted from fear of their young men being seized; and to procure 10 men, instead of one from each boat, who have been demanded from them, the crews have paid 106 L. 14 s. which exhausted the substance of some families, and hung long a debt on others.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 207)

In Aberdeen, County of Aberdeen, a very interesting observation and explanation was reported in the Old Statistical Accounts with regards to the employment of men and women. “Most of our manufactures, especially the bleaching and thread-making businesses, employ a much greater number of women than of men; and the great manufacture of the place, the knitting of stockings, is carried on almost entirely by females. Accordingly, while most of our women remain at home, many of our young men emigrate to other places, in quest of more lucrative employment than they can find in this part of the country… Besides, the temptations of cheap and commodious houses, of easy access to fuel, and to all the necessaries and comforts of life, from our vicinity to the port and market of Aberdeen, and of the high probability of finding employment from some of the many manufactures carried on in the neighbourhood, induce many old women, and many of the widows and daughters of farmers and tradesmen, to leave the country, and reside in this parish, while their sons have either settled as farmers in their native place, or gone abroad, or entered into the army or navy. If to these observations we add, that in all parishes, in which there are several large towns and villages, most families need more female than male servants, the majority of females in this parish, great as it is, will be sufficiently accounted for.” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 178)

The need to work also extended to children. In Nigg, County of Kincardine, “the male children of the land people, from 9 and 10 years old, often herd cattle in summer, and those of all attend school in winter. The female children learn still earlier to knit and to read.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 207) In fact, in most cases children worked in the same areas of employment as women. Examples include: the mining and farming industries; the weaving industry, in particular preparing the yarn for the loom (see our post on ‘Women in Scotland: Manufacturing‘ for more information) and in the mills (as mentioned in one of our earlier posts and in the parish report for Dundee, County of Forfar, where “more than one-half of those employed in the mills are boys and girls from ten to eighteen years of age; the remainder are partly men and partly women of all ages.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 26))

In many parish reports, the hard-work and fortitude of women and children, is clearly displayed. However, in some parishes, there was no work available for them. In Kiltearn, County of Ross and Cromarty, it was noted that “considering the great number of women in the parish, it would be desirable that some manufacture should be introduced to employ the females, and children of both sexes; for it is a hard case, when a labouring man is unable to work by age or sickness, that his family has no means of earning a subsistence, however unwilling to work.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 288)

Wages

All parish reports in both the Old and New Statistical Accounts of Scotland give the typical wages of workers. Of course, women were paid much less than men. In Houston and Killallan, County of Renfrew, “men servants from L. 7 to L. 10 a year, if they are good ploughmen; women-servants, from L. 1 : 10 : 0 or L. 2 the half year, and upwards.” (OSA, Vol. I, 1791, p. 325)

There are plenty more examples of this, including:

Keig, County of Aberdeen – “The wages of farm-servants were, of men, from L.4, 10s. to L.6, 10s. or L.7; of women, from L.2 to L.3 per annum; of day labourers, 6d. with maintenance. Reapers were hired for the harvest, the men at L.2 and the women at L.1.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 957)

Dollar, County of Clackmannan – “The wages of men labourers are from 10 d. to 1 s. per day; in harvest, they receive 13 d. or 14 d. per day; and for cutting hay, 1 s. 6 d. The wages of women who work without doors, at hay-making, weeding potatoes, etc. are 6 d. per day; except in harvest, when they receive 10 d. per day: out of which wages, both men and women furnish their own provisions.” (OSA, Vol. XV, 1795, p. 164)

Auchtertool, County of Fife – “Men servants used to get 6 L. Sterling for the year; and women, 2 L. 10 s.: But a man servant, now, receives 8L.; and a woman 3 L., for the year.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 119)

Dundee, County of Forfar – “The following are the average wages at present paid at the mills, and generally in the linen manufacture in Dundee, viz. to flax-dressers from 10s. to 12s. weekly; girls and boys, 3s. to 6s.; women, 5s. to 8s.; weavers, 7s. to 10s.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 26)

Kingussie, County of Inverness – “A shilling per day is reckoned but very ordinary wages. Many receive 15 d. and 16 d. and some refuse to work under 18 d. The wages of women, however, is not in proportion; during harvest, and when employed at peats, they receive 8 d. a day, and at every other season of the year only 6 d.” (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 39)

The unfair nature of this disparity in wages was highlighted by the Rev. Mr. Joseph Taylor, who wrote in the parish report for Watten, County of Caithness:

“Women, qualified for tending cattle throughout the winter, driving the plough, and filling the dung cart in spring, had only about 8 s. Sterling, with just half the subsistence allowed the man. Why so little subsistence was and still is allowed to women, no good reason can be assigned. Established customs cannot always be accounted for, nor are they easily or suddenly overturned. This article of wages, however, has of late risen, and still continues to increase.” (OSA, Vol. XI, 1794, p. 274)

There are some very interesting descriptions and comments on wages in the Statistical Accounts. In Colinton, County of Edinburgh, it was reported that women and boys were paid the same amount of money (9d. per day) working in the fields and that “in the time of harvest and of lifting potatoes, their wages are regulated by the hiring market, which is held in Edinburgh every Monday morning during, the season.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 124)

Weavers in Cults, County of Fife, “while in winding the smaller bobbins for the wool… usually employ their wives or children. At this latter employment, if done for hire, from 2s. 6d. to 3s. may be made per week.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 573)

Another interesting comment, this time on the relationship between technology and wages, can be found in the parish report of Moulin, County of Perth:

“The consequence of yarn selling high is an immediate rise in the wages of women servants. Should the machines for spinning linen yarn come to be much and successfully used, so as to reduce the price of spinning, that effect will be severely felt in this country. Single women may, perhaps, find employment in some other branches of manufacture; but it does not appear in what other way married women, who must fit always at home with their children, can contribute any thing to the support of their families.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 63)

In St Vigeans, County of Forfar, the correlation between wages and skill, as well as conditions of employment, are highlighted:

“with respect to the wages of those employed in the factories here, though considerably lower than they have been, we should say, that, looking to age and the preponderance of females, they are perhaps the best paid class employed in the linen trade, with the exception of hacklers. Spinners, who are all girls of fifteen to about twenty-five years of age, earn from 5s. 4d. to 6s. 6d. per week; reelers, from 5s. to 6s.; and those in the preparing departments, from 3s. to 6s., according to the nature of the work assigned to each. The department requiring early and indispensable previous training is the spinning. It consists in expertness and facility in uniting broken threads, and which can only be efficiently acquired by the young. In the present improved state of machinery, the labour is by no means irksome; and hence it is that it is no uncommon thing, in passing through the spinning-flat of a well-conducted mill, to find many of the girls employed in reading. Spreaders, feeders, and reelers have a more laborious work to perform; but the persons employed in these capacities are, for the most part, full-grown women; and, generally speaking, they are allowed a longer time for meals and relaxation than the rest of the hands. The whole of the workers, men, women, and children are at liberty to leave their employment on giving four weeks; notice, in some cases even one week being held sufficient. Hacklers are paid at the rate of 2s. for every hundred weight of rough flax which they dress; and it is no unusual thing for a steady hand, with the assistance of an apprentice, whom he allows 3s. 6d. to 5s. 6d., to earn L. 1, 4s. per week. The average wages, however, of this class, including those who have no apprentices, does not perhaps exceed from 10s. to 12s. per week.*

* In the interview between the writing of this article, in January l842, and the correcting of the proof-sheet in October following, a farther reduction in wages has taken place of five to ten per cent.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 506)

In the parish report of Forfar, County of Forfar, a comparison is made between wages at that time and formerly. “About 60 years ago, a principal farm servant might have been had for 35 s. or 40 s. the half year, and a woman for 40 d. besides her harvest fee. Now many men servants receive L. 12 Sterling per annum, and few or none less than L. 7; and women servants have from L. 3 to L. 4 a year with a lippie of lint ground, or some equivalent called bounties. A man for the harvest demanded formerly half a guinea, now he asks from 30 s. to 40 s, and is sometimes intreated to take more. A female shearer formerly received from 8 s. to 10 s. now 20 s and upwards. Male servants in agriculture, besides their wages, get victuals, or two pecks of meal a-week in lieu thereof, with milk which they call sap. Cottars generally receives from L. 3 to L. 7 a year, with a house and garden, and maintenance of a cow throughout the year. On this scanty provision they live comfortably, and raise numerous families without burdening the public. A family of nine children has been reared by a labourer of this description without any public aid. The cottar eats at his master’s table, or has meal in lieu of this advantage. From 20 to 30 s a year are given to a boy, from 10 to 14 years of age, to tend the cattle or to drive the plough.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 532)

Conclusion

As can be gathered from above, the Statistical Accounts of Scotland contains a lot of information on wages, providing us with examples of differences between both jobs and those employed, whether it be men, women or children. It would be very interesting to make comparisons across parishes! The parish reports are also a great source of comment from the ministers who wrote them, illustrating people’s views on such things as the effect women working had on the community, and the discrepancy between men’s and women’s wages.

In our next post, we will continue to look at the effects society had on women in Scotland, including the existence of poor women and the establishment of female societies; women’s civil status; and women’s health.

Impact of the War on the University and the Art College

The following was written by Gillian McDonald, a MSc Scottish Studies intern, who spent some time in early 2013 looking at selected items in the archives of the two institutions and analysing how World War 1 changed things on the ground.

The First World War had an enormous impact on Scottish society as a whole, but it also had an important effect on specific institutions. The Minutes of the University Court provide an insight into how the war affected the University of Edinburgh, and similar official minutes and other records provide information about Edinburgh College of Art’s reaction to the Great War. During my eleven-week internship at the Centre for Research Collections at the University of Edinburgh, I was able to study this material in detail and discover the many ways in which the war altered the normal running of both institutions.

Perhaps the most obvious impact the war had was on the decreasing number of staff and students able to attend the University. Within the first few months of war, the University Court Minutes had already reported on several cases of members of staff applying for leave of absence in order to take up military service. As the war continued, and conscription was eventually introduced, these numbers only increased further. It was not just military service, however, that prevented members of staff from undertaking their normal duties; some staff members took leave of absence in order to do other war-related jobs. For example, Mycology Lecturer Dr Malcolm Wilson became a Pathologist in the County of London War Hospital, and Mr H.W. Meikle, Lecturer on Scottish History, took on a post in the Intelligence Section of the Ministry of Munitions for the duration of the war.[1] The Minute Books from Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) show a similar story, with many members of staff applying for leave of absence whether to join the military services or to undertake other kinds of war work. This affected janitors, attendants and secretarial staff as well as teaching staff; in July 1916 Attendant Thomas Monteith applied for leave of absence to join His Majesty’s Navy, whereas his colleague Robert Sloane undertook work in a munitions factory during wartime.[2] In most cases, both at the University and at ECA, positions were kept open for the staff members’ return and the institutions paid the difference when military pay was less than their usual salaries. This proved to be a huge drain both on funds and resources, as not only did the University and ECA have to pay partial salaries of absent staff, but those who remained in employment had to undertake extra work to keep classes running. In some instances, it was simply not possible to continue with so many absent members of staff; in June 1916 it was decided that Elementary Greek, Elementary German, Political Economy, Arabic, History of Medicine and Physical Methods in the Treatment of Disease should be suspended during the 1916-17 term.[3]

The absence of a great number of students proved to be an arguably even bigger problem. In 1914, the majority of income for Scottish Universities was derived directly from student fees, but with the bulk of students being military-aged men this income ground to a halt during the war. As early as January 1915, the Courts of the four Scottish Universities had arranged to establish a Conference and prepare a joint memorial to be sent to the Treasury in order to obtain additional funding.[4] This funding was granted due to the ‘special circumstances’ of the war, and continued throughout the conflict. The huge scale of the First World War created the need, for the first time, for widespread state intervention in the running of Scottish Universities. These grants did not end as soon as peace was declared; in May 1919 the Treasury paid the University of Edinburgh an annual grant of £53,000, as well as a non-recurrent grant of £20,000 to help the University restore itself to a pre-war standard.[5] ECA also required financial help to cover the deficit created by a lack of fee-paying students; the Scotch Education Department granted a payment of £8,679 for the session 1914-15, and other similar payments were made throughout the war.[6] Another source of income was from the Carnegie Trust; the newly created Conference of the four main Scottish Universities met regularly throughout the First World War to discuss financial issues, and were able to secure special grants from the Carnegie Trust.[7]

With so many young men absent from the University, one group of students were actually able to improve their position during the war. Women were a very small minority of students in 1914, but by the end of the war their presence had become more widespread in Edinburgh University. Female students had not previously been admitted to the University of Edinburgh Medical School, instead studying at Surgeon’s Hall. With an increasing number of female medical students due to the special circumstances of wartime, Surgeon’s Hall was no longer able to provide satisfactory accommodation and resources and so suggested in June 1916 that women should be admitted to the University to study Medicine. Following many letters and petitions, the following month saw the University agreeing to ‘make provision within the University for the instruction of women in the Faculty of Medicine’.[8] Throughout the war, the Women Students’ Union campaigned for better facilities for female students, but it was not until February 1919 that the University agreed to let out a property in George Square solely for their use.[9] The lack of available male staff also benefitted women as they were often appointed as substitute lecturers, assistants, demonstrators and examiners. The same could be seen at ECA; Dorothy Johnstone, for example, was appointed in place of Walter B. Hislop, an Assistant Teacher in the Drawing and Painting Section who served with the 5th Royal Scots during the war.[10] Perhaps due to the nature of courses on offer, female students already enjoyed a relatively prominent position at ECA so the war did not cause as major a change for them as it did for University students.

As well as the cancellation of some classes and extra provision for women in others, new classes were also introduced to help cater to the needs of a society at war. In June 1915 there were discussions to introduce a course in Military Science which would be open as a qualifying class to ‘all men who have served or are serving with His Majesty’s Forces’.[11] Following the introduction of conscription, however, the Lectureship on Military Subjects as suspended as there were no current or prospective students. Instead, more emphasis was put on ‘practical’ courses which would help keep the country running throughout the war, and aid in rebuilding it after peace was declared. In December 1917 developments began to improve the Forestry Department to cater for the extended teaching which was probable after the war. This began with the conversion of the Lectureship into a Chair, and then in May 1918 a special Diploma and Certificate in Forestry was established which would be open only to those who had served with His Majesty’s Forces during the war.[12] In May 1919 the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce gave the University £15,000 for the purpose of endowing a Lectureship in the subject of Industry and Commerce.[13] Some special courses were set up for demobilised men; schemes were introduced to provide education for invalided Colonial soldiers, and courses in Town Planning and Civic Design were to be provided to train discharged and disabled officers.[14] The Edinburgh Lipreading Association set up special classes at ECA for teaching lipreading to soldiers and sailors deafened in the war, and the men would also be able to attend Art classes whilst they were studying at the College. Convalescent Officers, who had some previous training in art, from Craiglockhart Hospital were also able to study at ECA without payment of fees.[15] It was common for both the University and ECA to admit those who had served in the war, as well as allied refugees, to classes free of charge or at a reduced rate. Some courses which had traditionally been a part of University teaching, however, declined in importance. Despite a Chair of German being established during the war there were strong objections to it due to popular anti-German sentiments, and steps were taken to ensure that no one was appointed to fill the position until after the war ended.[16]

As has been previously mentioned, the First World War saw increasing state intervention in Scottish Universities on a financial level, but during the war itself the state also had a physical presence within both the University of Edinburgh and ECA. The Local War Department took over the Edinburgh University Field Pavilion ‘for the purpose of billeting twenty-five men of the Army Service Corps’ in December 1916, and in February 1918 the Music Hall was commandeered by the Ministry of National Service.[17] The Board of Agriculture also made inquiries in January 1917 about taking over land belonging to the University in order to convert as much vacant land in the city as possible to allotments which were vital in the ‘present emergency’.[18] University premises were also used by other organisations and individuals for war-related activities; the Women Students Help Association used a room in the University as their Office and Committee Room to organise the provision of clothing and ‘articles of comfort’ for soldiers and sailors.[19] The government also had a noticeable presence at ECA during the war. The Food Control Department took over use of several classrooms in August 1917, and several other parts of the College were used by the Local Fuel and Lighting Department.[20] The Ministry for National Service also intended to take over a large portion of the building, but ECA was already overstretched and so it was decided to locate the offices for the Scottish Region Headquarters of the Ministry for National Service at the Royal (Dick) Veterinary School instead.[21]

As well as all these big changes, the war also had a significant impact on the day-to-day running of both institutions, causing many small disruptions and changes. Throughout the war, the University took out various types of Aircraft and Bombardment Insurance and Fire Insurance because of the potential threat of enemy attacks, and lighting regulations were also put in place. Perhaps now more associated with the Second World War, during the Great War “blackout” regulations were also strictly enforced by the City authorities and University buildings had to ‘avoid the display of unshaded lights after 7pm’. To comply with regulations, ECA had to obscure the glass roof of the Painters’ and Decorators’ classroom and the roof lights of the Design classrooms, as they were without blinds.[22] Due to the high cost of paper, the printing of the University of Edinburgh Library Catalogue was suspended until April 1919. Building repairs, the awarding of prizes and bursaries, and the appointing of new staff all had to be temporarily suspended during the war.[23] The already outdated Departments of Science and Medicine had suffered greatly from lack of repairs or upgrades during the war, and after peace was declared the huge influx of new students intensified this problem even further; the need for a ‘large building scheme … is now more than ever urgent’. This eventually led to the creation of the new King’s Buildings campus, the foundation stone of which was laid by the His Majesty on the 6th July 1920.[24] ECA also had to make cutbacks, with the Prospectus being revised in June 1916 to minimise printing and, after special Food Regulations were introduced, the Dining Hall staff had to ‘comply with the rules laid down for Restaurants’.[25]

As the war continued and many students and members of staff lost their lives, both the University and ECA had to consider the most appropriate way to remember those who had fought in the war. In December 1915 the University provided money towards a memorial service at St Giles Cathedral for students who had fallen in the war, but it was not until November 1917 that a Committee was appointed to create a Roll of Honour and collect memorial photographs. The Roll of Honour was published in the spring of 1920 and contained a Roll of the Fallen, with photographs, along with a record of war service and an introductory chapter on the war work of the University. A copy was given to a relative of each of the fallen, as well as to the various public institutions to which the University Calendar was also sent.[26] ECA began their preparations slightly earlier, with a Committee beginning to put together a Roll of Honour by April 1916. There were also discussions at this time about a suitable site and design for a memorial for the fallen to be erected after the war ended.[27] The ECA memorial took the form of a mural tablet which was unveiled on the 27th June 1922, and recorded the names of five members of staff and eighty-six students who lost their lives during the Great War.[28] The University’s memorial, costing approximately £2,000 and located on the west wall of the Old College Quadrangle, was designed by Sir Robert Lorimer and was unveiled on the 19th February 1923.[29]

The information in the minutes of the University Court and College Committee meetings suggests that the University of Edinburgh and ECA had, on the whole, largely similar experiences of war. There is a noticeable difference, however, in the way each institution discusses the war, especially in relation to the staff and students who left Edinburgh to join the military forces. The University Court Minutes remain very formal and there is little mention of where staff or students went or what happened to them. On the other hand, the Minutes of the ECA Committee and Board meetings, which are the records most directly comparable with the Court Minutes, include far more personal information about those who signed up. In most instances, when staff applied for leave of absence the Committee also recorded which battalion they joined, and sometimes where they were stationed or if they had been involved in any major battles. Perhaps because of ECA’s smaller size, it was much easier to “keep track” of those who had joined the forces. In addition to the official Minutes, there is also a Memorial Journal, put together by Miss Agnes L. Waterston, which records in detail information about staff and students involved in the war, along with press cuttings and photographs. Waterston was also Secretary and Treasurer of the War Comforts Fund which helped to organise many fundraising activities throughout the war, details of which are often recorded in the Minutes. These records, along with the ECA Letter Books, help to build up a much more personal view of the war in which ECA appears almost as a small, close-knit community rather than a formal institution. The University records, however, present a much more clinical picture where the focus is on the official running of the institution itself rather than the people who worked and studied there. It must be remembered, however, that the University Court is an organisation which is supposed to deal with mainly financial and administrative matters, but it is interesting to see a contrast between the minutes of the University and ECA nonetheless. Unfortunately, due to time constraints, I was unable to study additional records from the University of Edinburgh – such as the Senatus Minutes – or determine whether any records similar to the ECA Memorial Journal exist; this is certainly an area of study which merits more attention.

[1] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 529, 19th July 1915’, University of Edinburgh Court Minutes, Volume XI, January 1912 – April 1916, p597; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 546, 22nd January 1917’, University of Edinburgh Court Minutes, Volume XII, May 1916 – July 1920, p110

[2] ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 6th July 1915’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.7, October 1914 to July 1915, p87

[3] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 539, 12th June 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p21

[4] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 522, 18th January 1915’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p503-4

[5] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 571, 12th May 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p476-77

[6] ‘Meeting of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 1st February 1916’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No. 8, October 1915 – July 1916, p35

[7] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 536, 13th March 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p682

[8] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 539, 12th June 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p21-22’ ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 540, 10th July 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p30

[9] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 568, 17th February 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p434

[10] ‘Letter, 20th November 1914’, Edinburgh College of Art, Letter Book, No. 14, p184

[11] ‘Minutes of Meeting’ No 527, 14th June 1915’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p569-70

[12] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 556, 17th December 1917’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p251; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 561, 6th May 1918’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p310

[13] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 571, 12th May 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p480-81

[14] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 565, 18th November 1918’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p383

[15] ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 13th March 1917’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No. 9, October 1916 – July 1918, p39; ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 11th December 1917’ Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.9, October 1916 – July 1918, p15

[16] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 550, 14th May 1917’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p 153

[17] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 545, 18th December 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p97; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 558, 18th February 1918’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p267

[18] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 546, 22nd January 1917’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p111

[19] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 520, 16th November 1914’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p487

[20] ‘Meeting of the Sub-Committee of the Board of Management, 14th August 1917’, ECA Minute Book, No.9, p4; ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 5th November 1918’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.10 October 1918 – July 1920, p9-10

[21] ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 5th March 1918’, ECA Minute Book, No.9, p27

[22] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 543, 23rd October 1916’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p60; ‘Meeting of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 1st December 1914’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.7, October 1914 – July 1915, p22

[23] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 567, 13th January 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p402-3

[24] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 567, 13th January 1919’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p404; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 585, 18th October 1920’, University of Edinburgh, Court Minutes, Volume XIII, October 1920 – July 1924, p1

[25] ‘Meeting of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 6th June 1916’, Edinburgh College of Art, Minute Book, No.8, October 1915 – July 1916, p70; ‘Meeting of the Board of Management, 8th May 1917’, ECA Minute Book, No.9, p53

[26] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 532, 13th December 1915’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XI, p637; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 577, 19th January 1920’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XII, p623

[27] ‘Minutes of the College Committee of the Board of Management, 4th April 1916’, ECA Minute Book, No.8, p56

[28] ‘Note, March 1919’, Edinburgh College of Art, War Memorial Papers; ‘Note, February 1920’, ECA, War Memorial Papers; ‘Invitation, June 1922’, ECA, War Memorial Papers

[29] ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 605, 17th July 1922’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XIII, p302; ‘Minutes of Meeting, No 608, 18th December 1922’, UoE Court Minutes, Volume XIII, p331

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....