Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

Rare Books – Expect the Unexpected. 3

Hippogriffs, Rabbits, Skyship Ports and Mars: Fantasy Worlds

In our third visit to the student Notgeld and its connections with the exhibition, we move into the realms of fantasy. Some of the students realised that while their Notgeld needed a sense of place, they could improve on the world we have, and design for a better one.

Let us start by letting Naomi Sun lead us to the best of better places: Utopia:

“Here is UTOPIA.

A place for you to escape from the REAL.

You can finally be YOU,

though that will not be long.”

“Tickets are limited.

Please collect your notes and use them wisely.”

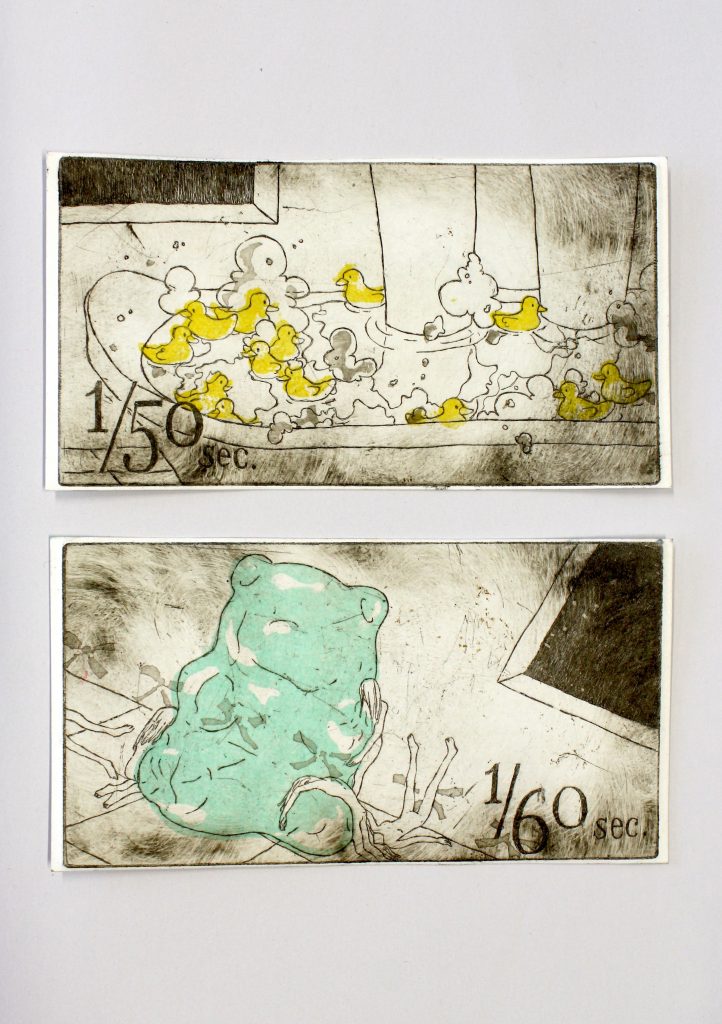

We were particulary impressed with Naomi’s work, as she was the only student to use etching to produce her notes.

Sammi Duong looked to Space, and made a better world on Mars:

“These banknotes are made for a future when we inhabit Mars and are named after the Mars Rover. Together they narrate the process in which humans made Mars habitable.

They were made digitally on Photoshop then risograph printed with red and gold ink.”

Zhaoyang Chen invented a world of rabbits.

“I designed these notes for an imaginary country populated by rabbits. The name of this country is Rabiland, I got the inspiration from Zootopia. The design and layout of the notes are based on modern Chinese notes.”

These also explore space: the third note of the set, which is in the exhibition but not illustrated here, shows the rabbits in very natty space suits.

Shannon Law and Valeria Mogilevskaya have both invented imaginary lands.

Shannon:

“My notes (Oceys) are for a fantasy fishing village that I based around some creative writing that my friend and I worked on. It originally was a market town with watchtowers surrounding it, I changed this due to the colour palette I was using and the style of buildings that were evident in medieval fishing villages.”

Valeria

“Ythers’Narth is a fictional country in a steampunk world, it is a mountainous and beautiful country which presents a scenic idyllic lifestyle to the rest of the world but in reality the strict laws and controlling government make life there far from free. These notes, issued by the capital city and carefully monitored by the nobility show parts of the country people are meant to look up to – the rich history and older civilization Ythers’Narth gets its name from and its people are descended from; the picturesque mountain ranges and fields of golden wheat; the immensely popular sky ship ports that people from all over the world fly to.”

The other exhibits some imagined lands – there are the examples from our collection of American comics, Batman, Spiderman and the irresistably-named “Ms. Tree”, which we cannot reproduce here for copyright reasons.

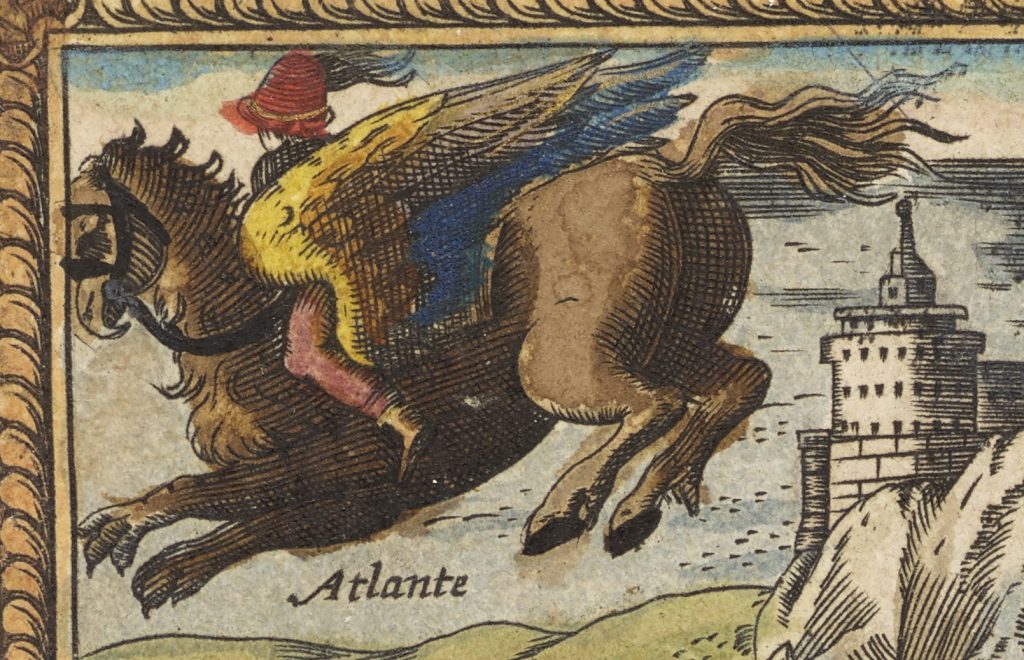

However, we can reproduce a fantasy creature, which would be worthy to inhabit any of the students’ fantasy lands. A hippogriff, from Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso. In the story the knight Astolfo travels by hippogriff to Ethiopia (which is clearly off the edge of the page), to seek a cure for Orlando’s madness, brought on by being jilted in love.

Hippogriff, from Orlando Furioso

Highland Childhoods in the Old Statistical Accounts – Part 1

Guest blog post

It is always wonderful to discover first-hand how people use the Statistical Accounts of Scotland. Two MLitt students of the University of the Highlands and Islands, Helen Barton and Neil Bruce, have carried out research on gender and family in the Highlands using the the Statistical Accounts of Scotland. They have written a blog post, divided into two parts, providing us with the results of their research. Below is part one, covering the themes of health and disease and family structures of children living in the Highlands.

________________________________________

Last year as part of our Masters course, we considered ‘Gender and the Family’ in the Highlands. We were challenged to use the Statistical Accounts to research the experience of childhood. We know very little about children in the region in the pre-Clearance era, and what little we do know is about the offspring of the elite, “the formal education and socialisation of children where it yielded a written record is more easily understood” (S. Nenadic, Lairds and luxury: the Highland gentry in Eighteenth-century Scotland (Edinburgh, 2007), p. 43).

An historian focusing on lost English society, Peter Laslett found the “crowds and crowds of little children … who were a feature of any pre-industrial society” are often missing from the record. Margaret King broadened this point across Europe: “We know less about the course of childhood itself, the socialization of the young, and the lives of the poor, always a black hole” (P. Laslett, The World We Have Lost (London, 1971), pp. 109-110, quoted in H. Cunningham, ‘The Employment and Unemployment of Childhood in England c. 1680-1851’, Past & Present, No. 126 (1990), p. 115; M. L. King, ‘Concepts of Childhood: What We Know and Where We Might Go’, Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 60, no. 2 (2007), p. 388).

Sir John Sinclair included three questions relating to children:

- The parish’s school population

- Family sizes

- The number of under-ten-year olds.

With this limited and “unwitting testimony” provided by the authors of the parish reports, the historian can glean an understanding of what children’s lives involved (A. Marwick, The Fundamentals of History, accessed 26th June 2018).

In our research we focused on the Outer Isles, Skye and the Far North, and the themes of

- Health and Disease

- Family Structures

- Work

- Education

We’ll cover the first two sections in this blog and the other two in part two.

Health and Disease

The reports frequently refer to children (and families) having a high risk of contracting and succumbing to disease. Surviving the first five to eight days was crucial in Lewis, where a “complaint called the five night sickness” “prevails over all the island” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 265, p. 281). The minister in Barvas thought “the nature of this uncommon disease … (was not) … yet fully comprehended by the most skilful upon this island” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 265). In Uig, it was described as epilepsy, where, other than two cases, all contracting it died; one survivor experienced severe fits, remaining “in a debilitated state”. Incomers had initial immunity, but even their new-born could contract it (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 281). Croup “proved very mortal, and swept away many children” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 279).

Smallpox had a “calamitous” effect, during an apparent epidemic, 38 children died within months; parents in Tarbat, Easter Ross, were “deaf” to the “legality and expediency” of inoculation (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, pp. 428-429). An epidemic in Harris in 1792 “carried off a number of the children”, most “inoculated by their parents, without medical assistance” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1794, p. 385). In Strath on Skye, and on North Uist, inoculation had “now become so general” that “the poor people, to avoid expenses, inoculate their own children with surprising success” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1793, p. 224; Vol. XIII, 1794 p. 312). In Tongue, in Sutherland, within five years of inoculations being introduced, smallpox had been virtually eradicated (OSA, Vol. III, 1792, p. 524). Even were a doctor affordable, there were only three surgeons and no physicians listed between Skye, the Small Isles, and the Outer Hebrides, all three in the latter, two of whom were on Lewis (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 250; OSA, Vol XIX, 1797, p. 281; OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 613).

Common “distempers” included colds, coughs, erysipelas (a skin infection) and rheumatism (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 275; OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 308; OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 264). The most comprehensive list of diseases was on Small Isles, including ‘hooping’ cough, measles, catarrh, dropsy of the belly, and pleurisy (OSA, 1796, Vol. XVII, p. 279).

It is more difficult to understand from the reports who cared for children when they were ill, or the role children had caring for others, in a community and society where “constant manual labour produced early arthritis … old age came prematurely, without the possibility of retirement for most” (H. M. Dingwall, ‘Illness, Disease and Pain’, in E. Foyster (ed), History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600 to 1800 (Edinburgh, 2010), p. 114). In rural Sweden, Linda Oja found that both parents had roles in caring for sick offspring (L. Oja, ‘Childcare and Gender in Sweden’, Gender History, Vol. 27, no. 1 (2015), p. 86). Correlating the inter-relationship between diet, health, life expectancy and diseases requires deeper investigation.

Family Structures

The family and work for children of the Highlands and Islands was intertwined. As ordinary daily family life was not the focus of the Accounts’, any details have to be discerned from what they recorded about ‘industry’, wage costs and general passing comments about local living conditions and culture.

Where detailed population statistics were recorded, they demonstrate the average household size. A typical family was nuclear: two adults and four or five children, rising to between seven and 14 in the islands. In many areas, longevity was reported. Women bore children from their early twenties until as late as their fifties, grandmothers were suckling their own grandchildren in the Assynt area (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, pp. 207).

Marriage may have had romantic foundations, but for many was an economic partnership where both partners worked to achieve a living, either waged or unwaged. In Lewis, there was a pragmatic approach to widowhood; “grief … is an affliction little known among the lower class of people here; they remarry after ‘a few weeks, and some only a few days” (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, pp. 261-2). Consequentially, children gained step-parents. This claim does seem extraordinary and further investigation through other sources would be beneficial. Nonetheless, the economic hardship of widowhood is well illustrated by his blunt statement.

Families were also on the move in large numbers. The Highlands and Islands were not immune to changes in agricultural systems taking place in the Lowlands and elsewhere. Sir John Sinclair himself was an enthusiastic encourager of new scientific methods. He enclosed his own Caithness estate, changing its management, and introducing new breeds of livestock, including large non-native sheep flocks (M. Bangor-Jones, ‘Sheep farming in Sutherland in the eighteenth century’, Agricultural Historical Review, Vol. 50, no. 2 (2002), pp. 181-202). Many people were displaced to new crofts and settlements on the coast.

The population was declining rapidly in Highland straths, but overall was generally-rising. Couples reportedly married younger than had previously been the trend locally. This was often by the age of twenty, apparently lower than the national average of 26/27 years old. In Halkirk, the report comments on ‘prudential considerations [being] sacrificed to the impulse of nature’ as young people no longer had to wait for an agricultural tenancy (OSA, Vol. XIX, 1797, p. 23):

Before the period above mentioned, people did not enter early into the conjugal state. The impetus of nature was superseded by motives of interest and convenience. But now, vice versa, these prudential considerations are sacrificed to the impulse of nature which is allowed its full scope; and very young people stretch and extend their necks for the matrimonial noose, before they look about them or make any provisions for that state.

More research on the reasons for earlier marriages would be beneficial.

To be continued …

Rare Books – Expect the Unexpected: 2

Satire

This is the second in our series of posts based on the current exhibition in the Library Gallery, and the project by Edinburgh College of Art Illustration students, based on the album of Notgeld, emergency money, from the early 1920s.

Some of the original German Notgeld was satirical, containing harsh commentary on the world which created it. One of the students picked up on this idea, and produced a set of notes commenting on current U.S. politics. Rachel’s puns on the names of politicians, her comment the state of the economy and political institutions are all completely in the spirit of the satire used on the original Notgeld. What she did not know was that one of the other items in the exhibition contains satire just as biting, but four hundred years older.

Rachel Berman: Politics and Hyperinflation

“The starting point for my project bloomed from two persistent themes within the presentation of the authentic Notgeld: Politics and Hyperinflation.

Indeed, as an avid political cartoonist, I was intrigued by these notions and was compelled to apply these elements to the contemporary context.

For this, I imagined a near dystopian futuristic USA (2019 to be precise), in which our current Supreme Leader has rewritten the course of history by converting the US Dollar to the US Donald. This rookie mistake has resulted in extreme hyperinflation, to the point where 1 Dollar now equates to 100 Donalds.

Furthermore, our Leader-in-Chief has decided to rename the US Penny, the US Pence (after his Vice President Mike Pence) and the US Nickel, the US Kavanickel (after his newly appointed Supreme Court Justice).

Additionally I have played around with several details on each note/bill.

For the Donald, I have altered the numbers to read 007, a reference to James Bond, with whom the President believes he shares a likeness.

For the Pence, I have swapped the ‘United States Federal Reserve System’ with the ‘National Rifle Association’, as the latter bared a strong resemblance with the former and better depicted Mr. Pence’s values.

Finally, for the Kavanickel, I wanted to have this used as a legal acquittal for all ‘past’ offences. For this I modelled the colours after the Monopoly ‘Get out of Jail Free’ card. It is no secret that Judge K’s past has been tainted by many credible allegations of sexual assaults. Despite this, however, he, like many other white men, has managed to evade the consequences of his crimes. I wanted to pay particular attention to this white male privilege and illustrate this section of society’s entitlement mentality.

In conclusion, I added a cheeky ‘Made in China’ label to hone in on the blatant fact that our industries are being overrun by the Chinese government, and that despite Trump’s rhetoric, we are NOT number one.”

There is another piece of trenchant satire in the exhibition; Robert Parsons’ (sometimes known as Persons) response to the edict of Queen Elizabeth I against the Catholics of England (Cum responsione ad singula capita… Elizabethae, Angliae Reginae, haeresim Calvinam propugnantis, saevissimum in Catholicos sui regni edictum, 1592).

This has much in common with Rachel’s Notgeld, and much of contemporary political satire. Firstly it was calculated to gain the maximum circulation, in this case by being written in Latin and published in several European centres simultaneously. Latin was then the language for international communication, much as English is today, while the modern means of gaining wide coverage is, of course, to publish online. Parsons’ satire gains its effect by using all the techniques of argument which were appreciated in the sixteenth-century; complex formal rhetoric, references to classical literature and the Bible, and contemporary ideas of the ridiculous. The modern equivalents are the punning jokes, references to contemporary popular culture and vivid images, which Rachel exploits to the full.

The background to Parsons’ book is the attempted invasion of England by the Spanish Armada in 1588. In the aftermath a proclamation was issued by the English crown, though actually written by the Lord Treasurer, Lord Burghley, accusing English Catholics of being in league with the Spanish against the English state, and English Catholics living abroad as being dissolute criminals. The response was a co-ordinated and sophisticated series of publications from the English Jesuits in Europe, culminating in this.

Parsons avoids attacking the Queen herself, concentrating instead on the ministers who were responsible for the legislation. His style is to make them ridiculous, by interpreting their actions and beliefs as monstrous and re-telling events to make them preposterous (according to some modern commentators his was a more truthful account than the official English version of the story). He points out the ministers’ extra-marital affairs and controversial religious views, as making them unfit to legislate on religious matters. He compares them to evil politicians from English and Biblical history. This is a very similar approach to Rachel’s satire of contemporary politics, with the exception that it depends on words, rather than images, for its impact. We live in a much more visual world than the Elizabethans did: easily-transmitted film and photographs give the modern satirist possibilities for visual jokes which depend on the audience recognising the victim. Rachel exploits this to the full in her Notgeld, but it was something which was not open to Robert Parsons.

On trial: Age of Exploration

I’m pleased to let you know the Library currently has trial access to Age of Exploration, a digital primary source collection from Adam Matthew Digital. This database allows you to discover through archive material the changing shape of exploration through five centuries, from c.1420-1920.

You can access this digital resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 11th February 2019.

Screenshot from ‘Enluminure de Maître d’Egerton: Le Livre des merveilles’. c.1410-1412.

New to the Library: TradeLawGuide

New to the library for 2019, TradeLawGuide provides comprehensive and methodical research tools for WTO law. Its primary document collection includes the WTO agreements and instruments, jurisprudence, dispute settlement procedural documents and negotiating history. Designed to account for the important role of jurisprudence in the development of WTO law, a suite of citators provides comprehensive substantive references to WTO, pre-WTO and Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provisions as well as cross-references within jurisprudence to interpret provisions and update or distinguish jurisprudence. Annotated Agreements, Treaty Interpretation, Terms & Phrases, Subject Navigator, Dispute Settlement Body Minutes (for policy issues arising in jurisprudence) and Jurisprudence Pending provide additional value-added content. Sophisticated full-text search functions are provided for all research tools and document collections along with detailed summaries and commentaries on WTO jurisprudence.

Access TradeLawGuide via the main Databases AZ list, Law AZ list, Business and Management AZ list and DiscoverEd.

Rare Books – Expect the Unexpected. 1

A Sense of Place

If you have been passing the Main Library recently you will have seen the exhibition in the Library Gallery on the ground floor, of some of the more unlikely things to be found in the Library’s Rare Books collections. One exhibit you should not miss is the first thing you come to – the project by students of Illustration from Edinburgh College of Art (ECA), based on an album of German “emergency” banknotes from the years after the end of the First World War.

The schedule for printing the exhibition catalogue prevented us from including any of the student work in it, and in the exhibition itself we only had space for a selection of the student work, and none to include their own commentaries on it.

When we saw the students’ projects, one thing which struck us was how many of them link with items in the exhibition other than the Notgeld. These are entirely fortuitous connections; none of the group knew what the other exhibits were.

In this series of blog posts we want to showcase the student work, including the ones we couldn’t fit into the exhibtion, and make some of the juxtapositions with other exhibits which struck us when we were assembling it.

Notgeld

In Germany many local authorities issued “Notgeld”, “emergency money” during and immediately after the First World War. Initially, the diversion of all available metal to the war effort had caused a scarcity of small change. Locally-issued, low denomination notes, enabled the everyday econonomy to continue to function, even though they had the status only of tokens, and had no national authority behind them. They continued to be issued after the end of the war, into the early 1920s, when they were no longer strictly needed, but had become collectible. These notes were generally very attractive, celebrating the history, industry or culture of the locality which issued them, although they were sometimes satirical or contained propaganda or political messages. In our collections we have two albums full of notes from this late period, from all over Germany.

The ECA third year Illustration students were set a project to design their own Notgeld, exploring the features of the original Notgeld, looking at money and currency more widely, and developing their own ideas. They had to print their notes, using any printmaking technique available to them; some of these are referred to in their descriptions. (Risograph is a digital duplication and printing system, which builds up an image with layers of ink in different colours. The results are similar to screen printing)

The celebration of place is a strong theme in the original Notgeld. This was explored by the students in a number of different ways.

Several used the landscape, landmarks and distinctive features of their home towns.

Celeste John-Wood

My ‘Notgeld’ notes are designed for imagined use on the South Downs Way, a long distance national trail running through the South Downs in Sussex. The wildness and variety in

the environment inspired me to choose this location, and provided a rich resource from which I could develop my imagery and portray some key sites. For my notes, I aspired to create three very different denominations, portraying the contrast in the landscape and present a sense of each place’s distinct history. I have depicted Devil’s Dyke, the Charleston house (home to the Bloomsbury Group) and the Seven Sisters.

Daisy Ness

For my currency inspired by the German Notgeld, I chose my home of the Isle of Wight to create my notes for. I wanted to combine some of the local landmarks, such as Osborne House and the Needles, with the element of nature to create my work. To achieve the clean and precise look I was after, I decided to risoprint my design.

Lydia Leneghan

My inspiration for my notgeld notes was my hometown, Kilkeel, which is a small fishing town in Northern Ireland. My notes feature the most iconic parts of the town: the faerie trees, the harbour, and the legendary fish and chip van which is known across the country.

Philomena Marmion

Kaunas is the second biggest city in Lithuania. Founded in the 14th century, the city has gone through many changes: an important city in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, part of the Russian Empire, the temporary capital of Lithuania during the Interwar period, a city in the Soviet Union. Now Kaunas is in a cultural upheaval preparing for the role of the European Capital of Culture for 2022. All this history has left a mark on Kaunas and made it into the quirky, welcoming city that it is today. This set of Notgeld aims to show the special spirit of Kaunas by including elements unique to it: the green trolleybuses, the bison statue in the Oak Park, and the smiling sundial all with a backdrop of Soviet blocks of flats that make up the suburban areas of Kaunas.

Research Data Management Training for University of Edinburgh staff and students, Spring 2019

Following on from our blog post on the benefits of RDM training which was posted on the 15th of November, we have scheduled our in-person training courses for the Spring 2019 semester. A description of each course and its intended audience can be found on our Training and support resources webpage, alongside details of online training offerings. Courses can usually be booked through MyEd Event Booking approximately four weeks beforehand.

| Course | Dates & Times | Location |

| Creating a Data Management Plan | 16/01/2019@10:30-12:30 | Seminar Room 3, Chancellor’s Building (Little France) Map |

| 28/02/2019@14:00-16:00 | Murchison House, Room G.12 (Kings Buildings) Map | |

| 27/03/2019@14:00-16:00 | Appleton Tower, Room 2.07 (Central Area) Map | |

| Working with Personal and Sensitive Data | 13/02/2019@14:00-16:00 | Seminar Room 3, Chancellor’s Building (Little France) Map |

| 21/03/2019@10:00-12:00 | G.69 Joseph Black Building (Kings Buildings) Map | |

| 01/05/2019@14:00-16:00 | High School Yards, Classroom 4 (Central Area) Map | |

| Good Practice in Research Data Management | 24/01/2019@13:30-16:30 | Murchison House, Room G.12 (Kings Buildings) Map |

| 22/02/2019@ TBC | TBC | |

| 05/03/2019@13:30-16:30 | EW11, Argyle House, 3 Lady Lawson Street (Central Area) Map | |

| 05/04/2019@09:30-12:30 | Seminar Room 6, Chancellor’s Building (Little France) Map | |

| Managing Your Research Data | 17/01/2019@10:00-12:00 | Room B.09, Institute for Academic Development, 1 Morgan Lane, (Holyrood) Map |

| 05/02/2019@10:00-12:00 | Lister Learning and Teaching Centre – Room 1.3 (Central Area) Map | |

| 15/03/2019@10:00-12:00 | Seminar Room 5, Chancellor’s Building (Little France) Map | |

| 12/04/2019@10:00-12:00 | Room B.09, Institute for Academic Development, 1 Morgan Lane, (Holyrood) Map | |

| 25/04/2019@14:00-16:00 | G.69 Joseph Black Building (Kings Buildings) Map | |

| 18/06/2019@10:00-12:00 | Room B.09, Institute for Academic Development, 1 Morgan Lane, (Holyrood) Map | |

| Handling Data Using SPSS | 12/02/2019@13:30-16:30 | Room 1.08, First Floor, Main Library, George Square (Central Area) Map |

| 02/04/2019@13:30-16:30 | EW10, Argyle House, 3 Lady Lawson Street (Central Area) Map | |

| Data cleaning with OpenRefine | 07/02/2019@13:30-16:30 | Lister Learning and Teaching Centre ,2.14 – Teaching Studio, (Central Area) Map |

—

Kerry Miller

Research Data Support Officer

Research Data Service

Library and University Collections

Crime and punishment in late 18th-early 19th century Scotland: Causes of crime and crime prevention

This is the second in our series of posts on crime and punishment in 18th-19th century Scotland. This time we are looking at what the parish reporters thought were the causes of crime, as well as what measures were being put in place help prevent crime. There are some very interesting opinions on both these subjects found in the Statistical Accounts.

Reasons for crime

- Alcohol

It is not surprising to read that crime was mostly attributed to alcohol, or, more specifically, drunkenness! There are some very damning views shared in the parish reports. The Rev. Mr Thomas Martin wrote in the parish report for Langholm, County of Dumfries, “let the distilleries then, those contaminating fountains, from whence such poisonous streams issue, be, if not wholly, at least in a great measure, prohibited; annihilate unlicensed tippling-houses and dram-shops, those haunts of vice, those seminaries of wickedness, where the young of both sexes are early seduced from the paths of innocence and virtue, and from whence they may too often date their dreadful doom, when, instead of”running the fair career of life” with credit to themselves, and advantage to society, they are immolated on the altar of public justice.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 605)

In Tinwald and Trailflat, County of Dumfries, it was reported that “there are at present 2 small dram-shops in the parish which we have the prospect of soon getting rid of. They have the worst possible effect upon the morals of the people: and there is scarcely a crime brought before a court that has not originated in, or been somehow connected with, one of these nests of iniquity.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 50)

‘A drunken brawl in a tavern with men shouting encouragement’, 19th century wood engraving after A. Brouwer. [Wellcome Images, [CC BY 4.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

The cheap cost of alcohol, as well as the number of ale-houses in existence, was believed to be a factor in the higher level of crime. In the parish of Orwell, County of Kinross, “in consequence of the low price of spirits within these last six or eight years, there have been more petty crime and drunkenness than was formerly known.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 66)

It is fascinating to read the parish report from Hutton and Corrie, County of Dumfries, which states that “in 1834, the House of Commons appointed a Select Committee of their number to take evidence on the vice of drunkenness. The witnesses ascribe a large proportion, much more than the half of the poverty, disease, and misery of the kingdom, to this vice. Nine-tenths of the crimes committed are considered by them as originating in drunkenness… The pecuniary loss to the nation from this vice, on viewing the subject in all its bearings, is estimated by the committee, in their report to the House of Commons, as little short of fifty millions per annum. ” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 550)

- Itinerant workers

In the parish of Corstorphine, County of Edinburgh, “the persons there employed are collected from all the manufacturing towns in England, Ireland, and Scotland. They are continually fluctuating; feel no degree of interest in the prosperity of the place; and act as if delivered from all the restraints of decency and decorum. In general, they manifest a total disregard to character, and indulge in every vice which opportunity enables them to perform” and is further noted that “the influence of their contagious example must spread” to others in the parish. (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 461)

- Lack of religious upbringing and instruction

In some corners, crime was also attributed to a lack of religious upbringing and instruction. As mentioned above, there was a report made to the House of Commons on drunkenness and its affect on crime. “In London, Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin, Glasgow, and all the large towns through the kingdom, the Sabbath, instead of being set apart to the service of God, is made by hundreds of thousands a high festival of dissipation, rioting, and profligacy.” (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 550)

Govan, County of Lanark, was seen as a district “where there is no civil magistrate to enforce subordination, and to punish crimes, what can be expected, but that the children should have been neglected in their education; that many of the youth should be unacquainted with the principles of religion, and dissolute in their morals; and that licentious cabal should too often usurp the place of peaceable and sober deportment.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 295) It was also noted that “if neighbouring justices were, at stated intervals, to hold regular courts in so large villages, they might essentially promote the best interests of their country. They would be a terror to evil doers, and a protection to all that do well.”

In the parish report for Ardrossan, County of Ayrshire, it was remarked that “we have certainly too many among us who have cast off all fear of God, and yield themselves up to the practice of wickedness in some of its most degrading forms, yet the people in general are sober and industrious, and distinguished for a regard to religion and its ordinances. Not only is the form of godliness kept up, but its power appears to be felt, by not a few among them maintaining a conversation becoming the gospel.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 199)

Crime prevention

So, according to the parishes throughout Scotland, how best could crimes be prevented? As the parish report of Langholm, County of Dumfries, mentions, “it is much more congenial to the feelings of every humane and benevolent magistrate to prevent crimes by all possible means, than to punish them… Remove the cause, and the effects in time will cease.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 605) In the parish report of North Knapdale, County of Argyle, correcting criminal behaviour is preferable to punishment. “Such evil consequences can never be prevented without knowledge and education; and for this reason men, in power and authority, should pay particular attention to the subject.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 265)

In some quarters, punishments were considered too lenient. In the parish of Fetlar and North Yell, County of Shetland, “the punishments inflicted for such crime of theft, in particular, are so extremely mild, that they rather excite to the commission of the crime than deter from it.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 285) In some parishes trouble-makers and criminals were simply expelled from that city, town or parish, instead of being punished! As pointed out in the parish report of Muirkirk, County of Ayrshire, “this is neither more nor less, than to punish the adjacent country for sins committed in the town, to lay it under contribution for the convenience of the city, and free the one of nuisances by sending them to the other.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 609) (Although in the parish of Killin, County of Perth, “the turbulent and irregular [were] expelled the country to which they were so much attached, that it was reckoned no small punishment by them.” (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 384))

In Liberton, County of Edinburgh, it was felt that “nothing can remove the evil of assessments now, (which would be ten times greater, but for the efforts of the kirk-session,) but the subdivision of parishes, the diffusion of sound instruction and Christian principle amongst the people, and the removal of whisky-shops. Crime, drunkenness and poverty are always found together, and expending money upon the poor, except for the purpose of making them better, will as soon cure the evil as pouring oil upon a flame will quench it.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 27)

In the parish reports there is no lack of suggestions on how to deter crime and punish criminals.

- Suggestions

– Restrictions on selling alcohol

A very interesting suggestion was made in the parish report for Callander, County of Perth in November 1837. ” Considerable improvement has taken place within these few years in the management of the police of the country; yet there are many crimes allowed to pass with impunity. Would it not tend much to diminish crime if there were fewer licenses granted for selling, spirits, and more attention paid to the character of the persons to whom licenses are given?” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 360) A similar observation is made in the report for the parish of Stirling, County of Stirling, where “granting of licenses, without sufficient inquiry as to the character of the applicant” is believed to be one of the reasons for crime. (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 448)

In the report made to the House of Commons on drunkenness and its affect on crime “a great many of the witnesses recommended the prohibition of distillation, as well as of the importation of spirits into the kingdom.” The report also stated that religious institutions had a big part to play in “rooting out drunkenness, now appearing in every part of the kingdom”. (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 550)

In Kennoway, County of Fife, “the grand remedy, if it could be applied, would be to lay a restriction on the improper use of ardent spirits. Drunkenness is certainly the prevailing vice amongst us ; and is the originator, or at least inciting cause, to almost every mischief. Imprisonment for violent assault under its influence has of late been in two instances inflicted.” (NSA, Vol. IX, 1845, p. 381)

– Law enforcement and confinement

In the parish of Gargunnock, County of Stirling, a problem with vagrants is reported. “They spend everything they receive at the first ale-house; and for the rest of the day they become a public nuisance. The constables are called, who see them out of the parish; but this does not operate as a punishment, while they are still at liberty. It would be of great advantage, if in every parish, there was some place of confinement for people of this description, to keep them in awe, when they might be inclined to disturb the peace of the town, or of the neighbourhood.” (OSA, Vol. XVIII, 1796, p. 114)

The parish of Carluke, County of Lanark, reports specific measures taken against vagrancy. “The inconvenience and loss by acts of theft, etc. which many sustain by encouraging the vagrant poor of

other parishes, we have endeavoured to prevent here, not only by making liberal provision for the poor of this parish, and restraining them from strolling, under the penalty of a forfeiture of their allowance; but also by following out strictly the rule of St. Paul, “If any would not work, neither should he eat.” (2 Thess. iii. 10.) and the laws of our country with respect to idle vagrants.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 140)

Some parishes did not have any sort of, or very little, law enforcement in place.

Drymen, County of Stirling – “There is not a justice of peace, nor magistrate of any kind resident within the bounds of this parish neither is there a jail or lock-up house from the most westerly verge of the county onward to Stirling,–a distance of nearly fifty miles. The consequence is, that crime and misdemeanor frequently go unpunished, the arm of the law not being long enough nor strong enough to reach so far.” (NSA, Vol. VIII, 1845, p. 114)

Stromness, County of Orkney – “There is no prison in Stromness. This greatly weakens the authority of the magistrates, and is unfavourable to the morals of this populous district. Were an efficient jail erected, it would intimidate the lawless, and be an effectual means of preventing crime, and the lesser delinquencies.” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 38)

Thurso, County of Caithness – “at present the smallest misdemeanor cannot be punished by imprisonment, without sending the offender to the county jail of Wick, at the distance of 20 miles from Thurso, which necessarily occasions a heavy expense to the prosecutor, public or private, and, of course, is the cause of many offences passing with impunity, which would otherwise meet their due punishment.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 545)

Langholm, County of Dumfries – “Instead of banishing delinquents from a town or county for a limited time… would it not tend more to reclaim them from vice, to have a bridewell, upon a small scale, built at the united expense of the 5 parishes, where they could be confined at hard labour and solitary confinement, for a period proportioned to their crimes… The dread of solitary confinement, and the shame of being thus exposed in a district where they are known, would operate in many instances as a powerful preventive.” (OSA, Vol. XIII, 1794, p. 613)

Kilmaurs, County of Ayrshire – “Two bailies are chosen annually, but their influence is inconsiderable, having no constables to assist in the execution of their authority; the disorderly and riotous therefore laugh at their threatened punishments.” (OSA, Vol. IX, 1793, p. 370)

Employers and proprietors also had a role to play in deterring crime.

Kilfinichen and Kilviceuen, County of Argyle – “The Duke of Argyll, upon being informed of this complaint, gave orders to his chamberlain to intimate to his Grace’s tenants, and all the kelp manufacturers upon his estate, that whoever was found guilty of adulterating the kelp, would find no shelter upon his estate, and that they would be prosecuted and punished as far as the law would admit. This will have a good effect upon his Grace’s estate, and is worthy of imitation by the Highland proprietors of kelp shores.” (OSA, Vol. XIV, 1795, p. 182)

St Cyrus, County of Kincardine – “poaching for game has become much less common of late years, from the active measures employed by a game-association, instituted among the principal landed gentlemen of the county, for the punishment of this species of delinquency.”(NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 286)

- Increased religious instruction/services – spiritual and moral improvement

In Langton, County of Berwick, there were parochial visitations when there was discussion about any issues affecting the congregation between the presbytery and the elders, and then the congregation itself. “It is impossible to conceive a system more fitted to promote the diligence and faithfulness of ministers, or the spiritual and moral improvement of parishes. Its effects, accordingly, were visible in a diminution of crime, and an increase of personal and family religion among the surrounding districts.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 244)

In Hamilton, County of Lanark, “much has been said of the happy influence of Sunday schools in other places. If there were people of wealth and influence heartily disposed to strengthen virtue, to encourage good behavior, and to discountenance vice and irregularity, by establishing that institution here, in order to rescue the children of dissolute parents, from the danger of bad habits, to instruct them in the principles of religion, and a course of sobriety and industry, it is probable, they might be the happy means of restoring and improving the morals of all the people in this populous district.” (OSA, Vol. II, 1792, p. 201)

An interesting observation is made in the parish report of Hawick, County of Roxburgh. “The cases of gross immorality which occurred during the course of about thirty years before the Revolution, and when Episcopacy was predominant, were about double the number that took place during the course of thirty years after it, and when Presbytery was restored, which may justify the conclusion, that the exercise of discipline according to the constitution of the Church of Scotland is of signal efficacy in restraining the excesses of profligacy and crime.” (NSA, Vol. III, 1845, p. 392)

- Better street lighting

In Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh, “the frequent robberies and disorders in the town by night occasioned the town-council to order lanterns or bowets to be hung out in the streets and closes, by such persons and in such places as the magistrates should appoint,–to continue burning for the space of four hours, that is, from five o’clock in the evening till nine, which was deemed a proper time for people to retire to their houses.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 627)

Better street lighting was also identified as a form of crime deterrent in Dundee, County of Forfar. “In consequence of the rapid increase of the population of Dundee and surrounding district, and the ordinary provision of the law for preserving the public peace having become inadequate for the purpose, in 1824, the magistrates, with the concurrence of the inhabitants at large, applied to Parliament for an act to provide for the better paving, lighting, watching, and cleansing, the burgh, and for building and maintaining a Bridewell there… The police establishment has been of essential service to the inhabitants, with respect to the protection of their persons and property; although it cannot be denied that the streets are not much improved. The number of watchmen is too limited for the extent of the bounds, and the suburbs, which are generally haunts of the disorderly, are but poorly lighted.” (NSA, Vol. XI, 1845, p. 8)

________________________________

Conclusion

Writers of the parish reports had very clear opinions on the causes of crime and ways to tackle it. Alcohol and the resulting drunkenness was by far and away the most cited cause. It was deemed such a problem that, in 1834, the House of Commons appointed a Select Committee to investigate and report on ‘the vice of drunkenness’. some also blamed the lack of religious upbringing and moral and spiritual standards. As pointed out in our last blog post, a number of parishes reported that their citizens as, in the main, law-abiding, using such words as honest, sober, industrious, religious and moral. With regards to crime prevention, many parishes reported that the criminal system needed improving, including the building of bridewells and prisons, and the increasing of law enforcement. Specific measures against the licensing to sell alcohol and the cheap pricing of alcohol were also suggested. All this information that we find in the Statistical Accounts provides us with a fascinating insight into crime and its causes at that particular time. It allows us to think about how the causes of crime and preventative measures have changed (or stayed the same!) since the late eighteenth – early nineteenth centuries.

In our next post we will be looking at different types of punishment handed out to criminals in eighteenth and nineteenth century Scotland and how this correlates to the types of crime committed.

New to the Library: The Baltimore Afro-American

I’m happy to let you know that the Library now has access to the digital archive of The Baltimore Afro-American (1893-1988) from ProQuest Historical Newspapers. Founded in 1892 it is the most widely circulated black newspaper on the Atlantic coast and the longest-running family-owned African American newspaper in the United States.

You can access The Baltimore Afro-American (1893-1988) via the Databases A-Z list and Newspapers & Magazines database list. You can also access the title through DiscoverEd* Read More

Trial access to Chinese newspapers of modern China

Shanghai Library has provided us with a trial access to the digital archives of 6 modern Chinese newspapers, until 16 Feb 2019. The trial can be accessed on the same database platform as the Late Qing Dynasty Periodical Full-text Database 1833-1911 and Chinese Periodical Full-text Database 1911-1949, both of which are in the Library’s Databases A-Z list and Databases and the Databases by Subject for East Asian Studies list, or simply go directly to http://www.cnbksy.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/search/advance (EASE login is required).

Shanghai Library has provided us with a trial access to the digital archives of 6 modern Chinese newspapers, until 16 Feb 2019. The trial can be accessed on the same database platform as the Late Qing Dynasty Periodical Full-text Database 1833-1911 and Chinese Periodical Full-text Database 1911-1949, both of which are in the Library’s Databases A-Z list and Databases and the Databases by Subject for East Asian Studies list, or simply go directly to http://www.cnbksy.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/search/advance (EASE login is required).

The six Chinese newspaper archives are:

《小报》The Tabloids (1897~1949)

《新闻报》Sin Wan Pao (1893~1949)

《时报》The Eastern Times (1904~1939)

《大公报》(1902~1949/1952)Ta Kung Pao(1902~1949/1952)

《大陆报》The China Press (1911~1949)

《字林洋行中英文报纸全文数据库》The North-China Daily News & Herald Newspapers and Hong Lists (1850~1951)

Shanghai Library is digitising other Chinese and English newspapers of modern China. We will arrange a free trial when they are ready in 2019.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....