Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

December 15, 2025

New E-Resources for Literature

JSTOR’s Lives of Literature E-Journal Collection

We have added the newly available “Lives of Literature” collection to our Jstor subscription. This collection supports advanced literary studies and interdisciplinary research on writers and texts critical to curricula in literature. With its focus on journals that use an author or text as a starting place, Lives of Literature also fulfills a scholarly resource need for in-depth study and courses on a single author or text. It will contain 120 journals that are all new to JSTOR when completed.

Key thematic topics include:

- Medieval Authors & Texts

- Modernist Authors

- Victorian, Edwardian & Gothic Authors

- Literary Theorists

View the title list at https://www.jstor.org/titlelists/journals/livesoflitext-backfile-collection?filter=head_titles&fileFormat=xls

Further info

Access Jstor via the Databases AZ list, this e-resource is also available to University of Edinburgh alumni.

A user guide to this collection is available from https://guides.jstor.org/livesofliterature

Oxford Bibliographies – Literary and Critical Theory

Oxford Bibliographies – Literary and Critical Theory

We have taken out a subscription to Oxford Bibliographies – Literary and Critical Theory which currently contains 70 articles. As these articles are not yet available in DiscoverEd, please search the Oxford Bibliographies website directly – a user guide is available via the video below.

Further info

The following Oxford Bibliographies modules are available to the University of Edinburgh – American Literature, Anthropology, Biblical Studies, British and Irish Literature, Buddhism, Chinese Studies, Cinema & Media Studies, Classics, Criminology, Education, Hinduism, International Law, International Relations, Islamic Studies, Jewish Studies, Latin American Studies, Linguistics, Literary and Critical Theory, Medieval Studies, Music, Philosophy, Psychology, Social Work, Sociology, Victorian Literature. See http://oxfordbibliographiesonline.com/obo/page/subject-list for individual module title lists.

Access is available via the Databases AZ list.

To the city, in the city, for the city: Patrick Geddes in India

Our project archivist, Elaine MacGillivray, travels to India later this week to deliver presentations at the CEPT Archives (Architecture, Planning and Design) in Ahmedabad, and at the ARTISANS’ gallery in Mumbai. In advance of touch-down in India, we take a brief look at Geddes’ experience there.

Patrick Geddes and class of c1919, University of Bombay Department of Sociology and Civics (Ref: Coll-1869/11)

Patrick Geddes first travelled to India in the autumn of 1914. He was 60. Prompted by the success of Geddes’ urban regeneration projects in the Edinburgh Old Town, Lord Pentland, (the then Governor of Madras), had invited Geddes to travel to India to advise on urban planning issues. In that first of many seasons that Geddes was to spend in India he was accompanied by his eldest son Alasdair. Together, they travelled thousands of miles across the vast country, all the time surveying each of the cities they visited. After arriving at Bombay, they headed north to Ahmedabad, Ajmer, Jaipur, Agra and to New Delhi before travelling across India to Lucknow, Cawnpur, Allahabad, Benares, Calcutta and then southward to Madras.

Geddes had planned to show in India, his favoured tool of civic education, the Cities and Town Planning Exhibition. He faced an unfortunate setback when the ship transporting his exhibition to India, the Clan Grant, was sunk near Madras by the German ship, the Emden. Aided by friends and colleagues at home, a committee, led by H.V. Lanchester, collected and forwarded a replacement exhibition. The first shipment made it to Madras by December 1914. The exhibition, comprising over 3000 maps, prints and photographs and set out on a quarter-mile of wall and screen, opened at the Senate Hall of Madras University on 17 January 1915. Geddes went on to tour his Cities and Town Planning Exhibition across India. The exhibits make up much of the Patrick Geddes archive collections now held at the universities of Edinburgh and Strathclyde.

An example of the plethora of notes made by Patrick Geddes’ on India, its cities, institutions and culture (Ref:T-GED/12/1/191a)

Geddes worked tirelessly to survey and compose reports on Indian cities and towns, 13 alone in Madras. Lewis Mumford, in his introduction to Jaqueline Tyrwhitt’s Patrick Geddes in India (1947), wrote that throughout Geddes’ time in India he worked to promote his ‘broad humanistic outlook on the social aspects of civic improvement’.[1] To quote Geddes himself ‘town-planning is not mere place-planning, nor even work-planning. If it is to be successful, it must be folk-planning’.[2]

The measure of the success of a city survey depends on its appeal to the individuals that compose the city: upon its power to rouse each from his, often life-long, training of seeing himself as a self-interested economic man and therefore mere dust of the State – to realising himself as an effective citizen valuing…his contribution to his city, in his city and for his city.[3]

Cities and Town Planning Exhibition at University of Bombay (Ref: T-GED/1/7/21a)

After a season of touring the Cities and Town Planning Exhibition, surveying and reporting on Indian cities, Geddes returned to Scotland in the summer of 1915 to fulfil his teaching responsibilities as Chair of Botany at the University College Dundee. Thereafter, he continued to travel to India each autumn. In 1917 he was prevented from travelling home to Scotland due to the dangers of being attacked by German U-boats. Geddes, at this point, was accompanied by his wife Anna and together they planned a summer school in Darjeeling. They recruited renowned Bengali polymath, poet, musician and artist, Rabindranath Tagore. The school opened on 21 May 1917, and marks the beginning of Geddes and Tagore’s friendship.

It was in India in 1917 that Geddes was dealt the harshest of blows. In April, he received a telegram to advise that his eldest son Alasdair had been killed in action in France. He bore this news alone for four months, afraid that sharing the news with his dear wife Anna would accelerate her own illness. Devastatingly, his dearly beloved and stalwart companion, Anna, died at Calcutta in the summer of 1917. She was unaware that she had been predeceased by her son.

Bereft, Geddes continued to work tirelessly to survey and report on Indian Cities, advocating and adapting his ideas on ‘diagnosis before treatment’, ‘conservative surgery’, and ‘regional survey for regional service’ to Indian traditions and values. His attempt to study and understand the interaction between humans and their environment utilised a range of disciplines including biology, sociology, geography, geology, and town planning. Sometimes he would only spend one or two swift days surveying a city. In others cases, as for Indore, he would spend months, culminating in a two-volume planning report, published in 1918.

Geddes returned to Scotland for a period in 1919. In the summer of 1919, he was offered the Chair of Sociology and Civics at the University of Bombay, by the then vice-chancellor, Sir Chimanlal Setalvad. Now at the age of 65, Geddes accepted the offer. By 1924, Geddes’ health had deteriorated and his contract with the University of Bombay was to come to an end. The success or otherwise of Geddes’ terms at the University of Bombay are debated. Certainly, there is evidence that the University Senate expressed dissatisfaction at Geddes’ periods of absence (in some part due to his town-planning commitments in Palestine). Geddes left India in 1924 and settled in Montpellier in the south of France.

For more in-depth accounts of Patrick Geddes in India you may find the following publications a useful starting point:

- Boardman, P., The Worlds of Patrick Geddes, (1978)

- Fraser, B., A meeting of two minds: Geddes Tagore letters, (2005)

- Tyrwhitt, J., Patrick Geddes in India, (1947)

- Munshi, I., Patrick Geddes: Sociologist, Environmentalist and Town Planner, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 35, No. 6 (5-11 Feb 2000), pp.485-491

Elaine will be delivering presentations at the CEPT Auditorium, Ahmedabad on 1 March 2019, and at ARTISANS’, Mumbai on 5 March 2019. For further information please contact Elaine elaine.macgillivray@ed.ac.uk

[1] Tyrwhitt, J., Patrick Geddes in India, (1947), p.16.

[2] Ibid., p.22.

[3] Ibid., p.35.

Judaism and Jewish Studies: the work of John ‘Rabbi’ Duncan and Adolph Saphir

New College Library holds collections of and about a number of individuals who gathered material and wrote extensively on Judaism and Jewish Studies, motivated by their interest in the conversion of Jews to Christianity. Two significant figures in this area of interest are John ‘Rabbi’ Duncan and Adolph Saphir.

Duncan was a colourful, intelligent and, at times, tortured soul, one particularly gifted in the study of languages and in missionary work. Born in 1796, he obtained an MA from the University of Aberdeen in 1814. When he began his study of theology, he was still an atheist and did not convert to Christianity until 1826. Even thereafter, he had times of doubt before settling into firm belief.

John ‘Rabbi’ Duncan – portrait by Hill & Adamson

In 1840, having spent some years as an ordained minister, Duncan’s interest in Hebrew and his growing interest in the church’s work concerning the conversion of the Jews to Christianity led to his appointment as the Church of Scotland’s first missionary to the Jews. Stationed in Budapest from 1841-43, Duncan was remarkably successful in his work there converting, among others, the young Adolph Saphir and his family to the Christian faith.

But in 1843, following The Disruption, Duncan’s calling took him back to Edinburgh where he held the chair of Hebrew and Oriental Languages at the newly-founded New College, remaining in post there until his death in 1870.

Until recently, Duncan’s collection was not easily accessible but it can now be searched for online. Resources by, about or owned by Duncan can be found in DiscoverEd and also via this resource list compiled by Academic Support Librarian, Christine Love-Rodgers.

In 1843, one of Duncan’s converts, 13-year-old Adolph Saphir, came with him to Edinburgh from Budapest, his father being keen that the young Adolph improve his English and train as a minister of the Free Church. This process took some time and saw Saphir travel to Berlin, Glasgow and Aberdeen, becoming a student of theology at the Free Church College, Edinburgh in 1851. In 1854, Saphir, himself a Jewish convert, was appointed a missionary to the Jews. Saphir’s mission took him first to Hamburg and then, in 1856, to South Shields. Five years later, he moved to London where he remained until his death in 1891.

Adolph Saphir – photograph by T. Roger, Swan Electric Engraving Co.

Despite Duncan’s inner battles of the spirit and his lack of prowess as a formal teacher, his personal piety, linguistic and informal teaching abilities, as well as his success as a missionary, were impressive. Saphir and he contributed significantly to the collection of items in New College Library, particularly with reference to the Christian mission to the Jews during the 19th century. Their legacy is to the ongoing benefit of scholars of Judaism and Jewish Studies.

A small exhibition of some of our Duncan and Saphir material will run from 26th February-31st March 2019 in New College Library.

Bibliography

http://www.clan-duncan.co.uk/john-rabbi-duncan.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Duncan_(theologian)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolph_Saphir

https://archive.org/stream/rschsv028p1barr/rschsv028p1barr_djvu.txt

Mighty in the Scriptures: a memoir of Adolph Saphir, D.D./by Gavin Carlyle. J.F. Shaw and Co.; 1893.

Gina Headden, IS Helpdesk Assistant, New College Library and Christine Love-Rodgers, Academic Support Librarian, School of Divinity, New College.

With many thanks to Jessica Wilkinson from the School of Divinity who contributed so much to identifying and listing the relevant New College Library collections.

E-Resources on trial for LGBT+ History Month

Alongside our print book display in the main library, we are also trialling the following E-Resources for LGBT+ History Month:

LGBT Magazine Archive

LGBT Magazine Archive is a searchable archive of major periodicals devoted to LGBT+ interests, dating from the 1950s through to recent years. 26 leading but previously hard-to-find magazines are included in LGBT Magazine Archive, including many of the longest-running, most influential publications of this type. Of particular note, The Advocate is made available digitally for the first time. The Advocate is the oldest surviving continuously published US title of its type (having launched in 1967). LGBT Magazine Archive also includes the principal UK titles, notably Gay News and its successor publication Gay Times. More info about this e-resource can be found on the SPS Librarian Blog.

Trial ends 28th Feb. – for off campus access please use the University VPN

Archives of Gender & Sexuality

Archives of Sexuality & Gender provides a robust and significant collection of primary sources for the historical study of sex, sexuality, and gender. With material dating back to the sixteenth century, you can examine how sexual norms have changed over time, health and hygiene, the development of sex education, the rise of sexology, changing gender roles, social movements and activism, erotica, and many other interesting topical areas. This growing digital archive offers rich research opportunities across a wide span of human history. The database currently includes 3 collections: LGBTQ History and Culture since 1940, Part I and Part II and Sex and Sexuality, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century. More info about this e-resource can be found on the HCA Librarian blog.

Trial ends 18th March.

Further info

Visit our e-resources trials webpage for more details about currently running trials and to complete feedback forms on trialled e-resources as your comments influence purchase decisions.

Crime and punishment in late 18th-early 19th century Scotland: Types of punishment

In our last two blog posts in our series on crime and punishment we have looked at levels, types, causes and prevention of crime. But, how exactly did parishes in late 18th – early 19th century Scotland, and even earlier, punish offenders? It wasn’t just a matter of throwing people into prison. As we have found out in the last post, some parishes did not even have a bridewell or prison. Also, what was the correlation between the type of crime and type of punishment? We will find out in this post.

Punishments

It is fascinating to discover some of the crimes and resulting punishments detailed in the Statistical Accounts of Scotland. Examples include: in Leochel, County of Aberdeen, “breaking and destroying young trees in the churchyard of Lochell, [a fine of] one merk for each tree; letting cattle into mosses and breaking peats, 40S.; beating, bruising, blooding and wounding, L. 50;… putting fire to a neighbour’s door, and calling his wife and mother witches, L. 100… ” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 1125) and in Paisley, County of Renfrew, “1606, May 18.-Three vagabonds are ordered to be “carted through the street and the cart;” with certification that if they return, they shall be “scourged and burnt,” ie. we presume, branded on the cheek;… 1622, June 13.-Two women accuse one another of mutual scolding and “cuffing;” the one is fined 40s. the other is banished the burgh, under certification of “scouraging,” and “the joggs” if she returned… 1642, 24 January.-“No houses to be let to persons excommunicated and none to entertain them in their houses, under a pain of ten punds… ” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 182)

It was noted in the parish report of Glasgow, County of Lanark, that all the punishments given by the kirk session in Glasgow, whether it was “imprisoning or banishing serious delinquents, or sending them to the pillory, or requiring them to appear several Sabbath days in succession at the church-door in sackcloth, bare-headed and bare-footed, or ducking them in the Clyde,… no rank, however exalted, was spared, and that a special severity was exercised toward ministers and elders and office-bearers in the church when they offended. There was no favouritism.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 932)

Below we look more closely at punishments for particular crimes, many from times before the Statistical Accounts of Scotland.

- Punishment for adulterers

On the 16th August 1587, a Kirk session in the parish of Glasgow, County of Lanark, “appointed harlots to be carted through the town, ducked in Clyde, and put in the jugs at the cross, on a market day. The punishment for adultery was to appear six Sabbaths on the cockstool at the pillar, bare-footed and, bare-legged, in sackcloth, then to be carted through the town, and ducked in Clyde from a pulley fixed on the bridge.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 110) You can also read here, in the parish report for Glasgow, County of Lanark, what the punishment was for “a man excommunicated for relapse in adultery”, which involved being “bare-footed, and bare-legged, in sackcloth, with a white wand in his hand”!

As mentioned in the appendix for Edinburgh, County of Edinburgh, “in 1763-The breach of the seventh commandment was punished by fine and church-censure. Any instance of conjugal infidelity in a woman would have banished her irretrievably from society, and her company would have been rejected even by men who paid any regard to their character. In 1783-Although the law punishing adultery with death was unrepealed, yet church-censure was disused, and separations and divorces were become frequent, and have since increased. Women, who had been rendered infamous by public divorce, had been, by some people of fashion, again received into society, notwithstanding the endeavours of our worthy Queen to check such a violation of morality, decency, the laws of the country, and the rights of the virtuous. This however, has not been recently attempted.” (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 611)Punishment for witchcraft

There are several reports on witchcraft trials and punishments in the Statistical Accounts, a chapter of Scottish history which, by the late 18th-early 19th century, was seen as a disgrace. As noted in the parish report of Dalry, County of Ayrshire, “this parish was the scene of one of those revolting acts which disgrace the annals of Scotland, of condemning persons to the flames for the imputed crimes of sorcery and witch-craft. This case, which is allowed to be the most extraordinary on record, occurred in 1576. Elizabeth or Bessie Dunlop, spouse of Andrew Jack in Linn, was arraigned before the High Court of Justiciary, accused of sorcery, witchcraft, &c.” (NSA, Vol. V, 1845, p. 217)

During the 1590s, “the crime of witchcraft was supposed to be prevalent in Aberdeen as well as in other parts of the kingdom, and many poor old women were sacrificed to appease the terrors which the belief in it was calculated to excite. Few of the individuals who were suspected were allowed to escape from the hands of their persecutors; several died in prison in consequence of the tortures inflicted on them, and, during the years 1596-97, no fewer than 22 were burnt at the Castlehill.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 21)

In Erskine, County of Renfrew, “these unhappy creatures, (who seem by their own confession to have borne no good character,) were brought to trial at Paisley in the year 1697, and after a solemn inquest, they were found guilty of the crime of witchcraft, and sentenced to be burnt alive, which sentence was carried into effect at the Gallow Green of Paisley on Thursday the 10th June 1697, in the following manner: They were first hanged for a few minutes, and then cut down and put into a fire prepared for them, into which a barrel of tar was put, in order to consume them more rapidly.” (NSA, Vol. VII, 1845, p. 507) For more information on the crime of witchcraft read our blog post “Wicked Witches“.

Punishment for other crimes

You can find many more examples of punishments for a number of different crimes in the Statistical Accounts. In Blantyre, County of Lanark, “any worker known to be guilty of irregularities of moral conduct is instantly discharged, and poaching game or salmon meets with the same punishment.” (NSA, Vol. VI, 1845, p. 324) In Nairn, County of Nairn, “unfortunately, however, this spring two lads were tried and condemned at Inverness for shop-breaking and theft. One of them was hanged. It is surely much to be wished that his fate may prove a warning to others, to avoid the like crimes. The other young man (brother to the lad who was executed), has been reprieved” (OSA, Vol. XII, 1794, p. 392)

There are also some particular, infamous crimes reported in the parish accounts, including that of Maggy Dickson in the parish report of Inveresk, County of Edinburgh. “No person has been convicted of a capital felony since the year 1728, when the famous Maggy Dickson was condemned and executed for child-murder in the Grass-market of Edinburgh, and was restored to life in a cart, on her way to Musselburgh to be buried. Her husband had been absent for a year, working in the keels at Newcastle, when Maggy fell with child, and to conceal her shame, was tempted to put it to death. She kept an ale-house in a neighbouing parish for many years after she came to life again, which was much resorted to from curiosity. But Margaret, in spite of her narrow escape, was not reformed, according to the account given by her contemporaries, but lived, and died again, in profligacy.” (OSA, Vol. XVI, 1795, p. 34)

Many of the examples of punishments are actually from previous times of the Statistical Accounts, and, as for those for witchcraft, were by the time of the Statistical Accounts seen as barbaric. In the parish report for Campbelton, County of Argyle, it is noted that “five or six centuries seem to have made no change in manners, under the later Kings, or their successors, the Macdonalds; as we find the most barbarous punishments inflicted on criminals and prisoners of war such as putting out their eyes, and depriving them, of some other members.” (OSA, Vol. X, 1794, p. 542)

Castle Campbell – general view form the north east. [Photo credit: Tom Parnell [CC BY-SA 4.0] from Wikimedia Commons]

More evidence of such a punishment can be found at Fyvie Castle, County of Aberdeen.”The south wing has in front a tower called the Seton tower, with the arms of that family cut in freestone over the gate. The old iron door still remains, consisting of huge interlacing bars, fastened by immense iron bolts drawn out of the wall on either side; and in the centre of the arch above the door-way, a large aperture called the “murder hole,” speaks plainly of the warm reception which unbidden guests had in former times to expect.” (NSA, Vol. XII, 1845, p. 331)

Instruments of Punishment

As not all parishes, or even counties, had a bridewell or prison, instruments of punishment were being used, especially before the days of the Statistical Accounts. It had the added advantage of acting as a deterrent – making the punishment very public and, therefore, humiliating.

Jougs

Jougs are “an instrument of punishment or public ignominy consisting of a hinged iron collar attached by a chain to a wall or post and locked round the neck of the offender” as defined by the Scottish National Dictionary (1700-) found on the Dictionary of the Scots Language website. (Incidentally, this is a great resource to use if you come across words you don’t understand in the Statistical Accounts!)

In the parish report of Dunning, County of Perth, “there is no jail, but in lieu of it there is that old-fashioned instrument of punishment called the jougs.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 722) The jougs in Marykirk, County of Kincardine, were to be found “on the outside of the church, strongly fixed to the wall.” Interestingly, “these were never appropriated by the church, as instruments of punishment and disgrace; but were made use of, when the weekly market and annual fair flood, to confine, and punish those who had broken the peace, or used too much freedom with the property of others. The stocks were used for the feet, and the joggs for the neck of the offender, in which he was confined, at least, during the time of the fair.” (OSA, Vol. XVIII, 1796, p. 612)

In Yester, County of Haddington, the jougs were “fastened round neck of the culprit, and attached to an upright post, which still stands in the centre of the village, and is used for weighing goods at the fairs. Here the culprit stood in a sort of pillory, exposed to the taunts and missiles of the villagers.” (NSA, Vol. II, 1845, p. 166)Similarly, jougs were described in the parish report of Ratho, County of Edinburgh. “This collar was, it is supposed, in feudal times, put upon the necks of criminals, who were thus kept standing in a pillory as a punishment for petty delinquencies. It would not be necessary in such cases, we presume, to attach to the prisoner any label descriptive of his crime. In a small country village the crime and the cause, of punishment would in a very short time be sufficiently public. Possibly, however, for the benefit of the casual passenger, the plan of the Highland laird might be sometimes adopted, who adjudged an individual for stealing turnips to stand at the church-door with a large turnip fixed to his button-hole.* The jougs are now in the possession of James Craig, Esq. Ludgate Lodge, Ratho. * Since writing the above, we find that the jougs were originally attached to the church, and were used in cases of ecclesiastical discipline.” (NSA, Vol. I, 1845, p. 92)

In the parish report for Monzie, County of Perth the jougs belonged “to the old church of Monzie, taken down in 1830” and was described as thus: “It was simply an iron collar, fastened to the outside of the wall, near one of the doors, by a chain. No person alive, it is believed, has seen this pillory put in requisition; nor is it known at what period it was first adopted for the reformation of offenders; but there can be no doubt, that an age which could sanction burning for witchcraft, would see frequent occasion for this milder punishment. It is now regarded as a relic of a barbarous age, and has been affixed to the wall of the present church merely to gratify the curiosity of antiquaries.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 270)

The jougs in Dunkeld, Country of Perth, were not, as per usual, attached to the the church but to the old cross. “The old cross was a round pillar, on which was four round balls, supporting a pyramidal top. It was of stone, and stood about 20 feet high. The pedestal was 12 feet square. On the pillar hung four iron jugs for punishing petty offenders. The cross was removed about forty years ago.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 979)

Branks

In the parish report of Langholm, County of Dumfries, you can find a description of branks. “This was an instrument of punishment kept by the chief magistrate, for restraining the tongue. The branks was in the form of a head-piece, that opens and incloses the head of the culprit,–while an iron, sharp as a chisel, enters the mouth and subdues the more dreadful weapon within. Dr Plot, the learned historian of Staffordshire, has given a minute description and figure of this instrument; and adds, that he looks upon it ” as much to be preferred to the ducking-stool, which not only endangers the health of the party, but also gives the tongue liberty ‘twixt every dip, to neither of which this is at all liable.” When husbands unfortunately happened to have scolding wives, they subjected the heads of the offenders to this instrument, and led them through the town exposed to the ridicule of the people”. (NSA, Vol. IV, 1845, p. 421)

Conclusion

As can be seen from reading this and the previous posts, the Statistical Accounts of Scotland contains a wealth of information on crime and punishment. Many parish reports describe the crimes and subsequent punishments from olden times, sometimes showing a sense of disgust at their barbarous, unjust nature. In some instances, there are even physical reminders, with there being instruments of punishment still in the parish. This all illustrates how changes are made continually and how, by looking back, you can discover how far we have come.

Cataloguing the correspondence of Thomas Nelson & Sons

Cataloguing the correspondence of Thomas Nelson & Sons

Last January, our intern Isabella started a 10-week placement at the CRC, as part of her MSc in Book History and Material Culture. Using our online system ArchivesSpace, she is cataloguing part of the records of Thomas Nelsons & Sons Ltd., a British publishing firm founded in Edinburgh in 1798. So far, she has been dealing with correspondence, advertising material, and printed material relating to publishing, all dating from the end of the 19th century. Here are some of her most interesting finds:

1. W. H. Allen & Co. Copy

1. W. H. Allen & Co.: Pictured above is a beautiful embossing from the stationary of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd., a London based bookseller and publisher. The company were ‘publishers to the India office’ as can be noted on the seal. The coordination of a lion and a unicorn most likely represents the company’s work across Scotland and England.

2. There are three letters from one Mrs. Allan enquiring about the potential for her 15 year old son to take up an apprenticeship with Nelson & Sons. She describes her son as being a naturally gifted illustrator and when the company takes a bit long to reply she sends further letters describing how she and her son are ‘wearing of waiting’ for a response. Though the company eventually accepted samples of the young Mr. Allan’s work, he was not offered an apprentice position.

3. Lady Aberdeen Insignia

3. Lady Aberdeen Insignia: Pictured above is the signet of Lady Ishbel Aberdeen who wrote to the offices of Nelson & Sons on September 14th 1896, sending several copies of Canadian literary reports and magazines as well as personal letters inquiring as to whether the company would wish to send any penny or bargain literature they may have the copyrights for to Canada as she believes the country is in desperate need of ‘good, cheap literature.’ She speaks about her children’s magazine “Wee Willie Winkie” named after the Scottish fairy tale as well as the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC). Lady Aberdeen was the founder of the NCWC, an advocate for the creation of the Victorian Order of Nurses as well as a well-known supporter of the Canadian suffrage movement. The signet is a blue embossed crown containing her initials wrapped together with a vine-esque tie (information on Lady Aberdeen acquired via the Canadian Encyclopaedia).

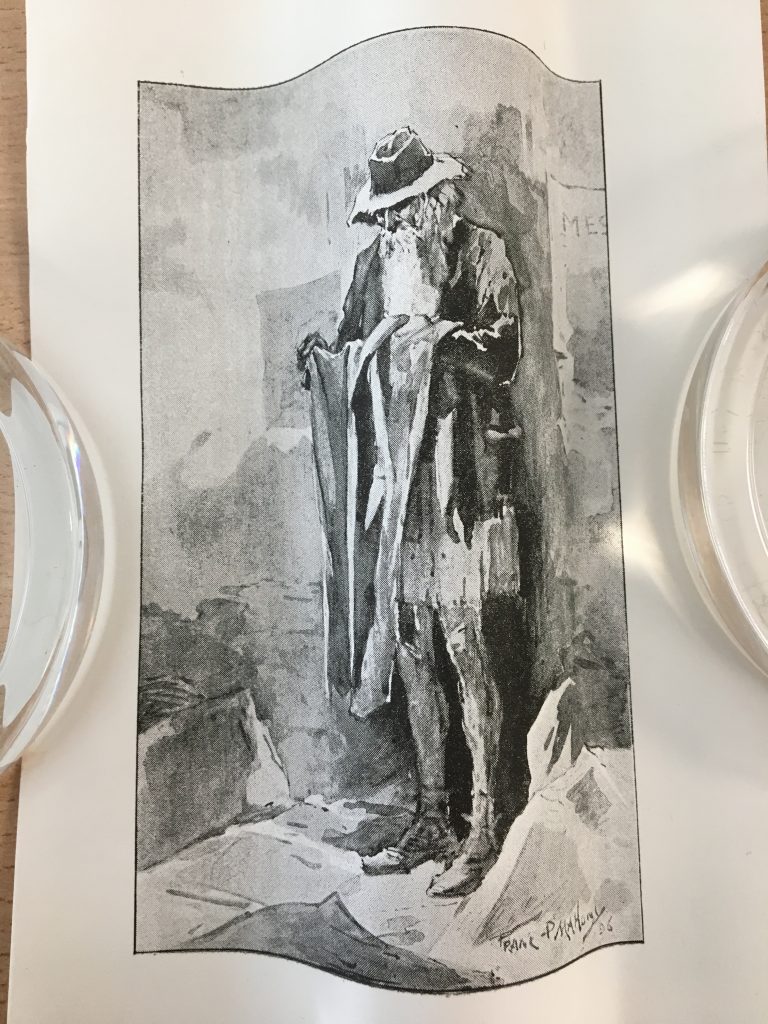

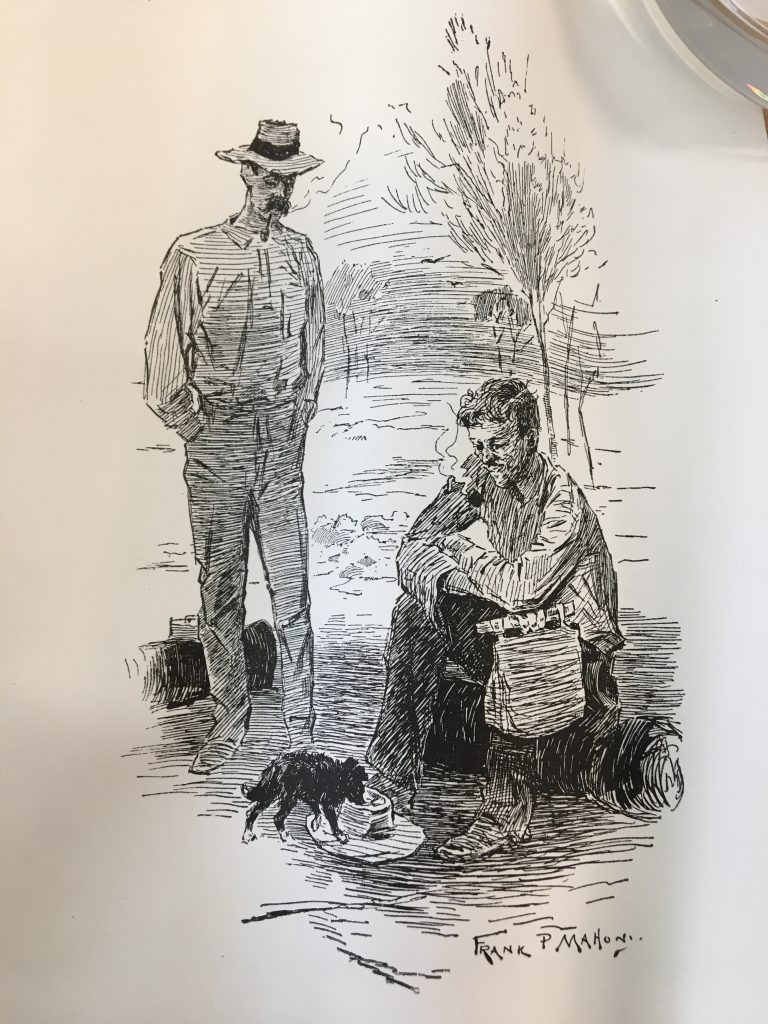

4. Frank Mahony (1)

4. Frank Mahony (2)

4. Frank Mahony (3)

4. Frank Mahony (4)

4. Frank Mahony (5)

4. Frank Mahony (6)

4. Frank Mahony: Pictured above are six printed illustrations from illustrator Frank P. Mahony. Mahony was an artist from Melbourne Australia whose work was used in the construction of the ‘New South Wales Reader’ a larger and heavily documented project undertaken by Nelson & Sons transcontinentally in congress with several agencies in Australia including leather workers, booksellers, and authors. As can be seen, the copies of the illustrations have been warped from years of being curled into a scroll-esque form at the centre of a group of letters and cost projections for the ‘New South Wales Reader.’ In order to examine each paper with minimal damage, two glass weights are placed at the edges of the copy pictures to examine them as a whole without compromising the form the paper has taken over years of storage.

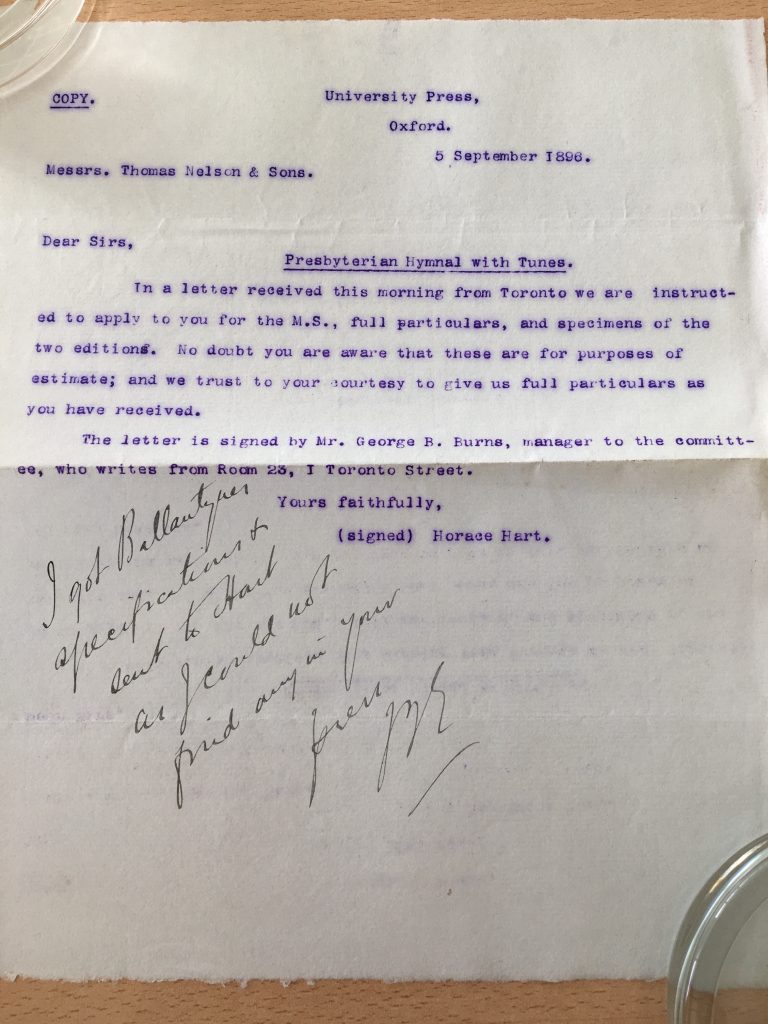

5. Oxford University Press

5. Oxford University Press: This letter addressed to Nelson & Sons is a copy of a letter from the University Press of Oxford requesting manuscript materials for the Presbyterian Hymnal with Tunes, a project which was spearheaded by Reverend James Anderson of Toronto. The initial correspondence regarding the publication of the Presbyterian Hymnal between Reverend Anderson and George Brown of Nelson & Sons deals mostly in obtaining or paying license for the use of tunes from other previously published hymnals. The various letters sent between the two men gives a glimpse into the nature of musical copyright laws and penalties in 1896 both in Canada, where the Reverend Anderson was based and in Scotland where Nelson & Sons offices were. The publication of the hymnal went on to be so successful that the University Press of Oxford requested to take up the publication of the piece as well.

6. Schwebius signature

6. Schwebius letter: Much of the cataloguing done for this archive requires some previous exposure to palaeography, or the study of dated handwriting. However, sometimes in deciphering particularly unclear script a second opinion or cross referencing is required to confirm the context of a letter in order to properly interpret the piece. For this letter, the name Schwebius, though written twice, was not entirely apparent in its spelling. The content of the letter referred to the sale of a foundry and various machines from a leatherworker in New York. The cataloguer referred to a digitized directory from the library of Hoboken, New York which not only lists the recipient of this letter, a George Schwebius, but mentions details of his business which were substantiated by the letter from the Nelson Archive. Corroborating information across archives and databases allowed not only for the correct spelling of the sender’s name to be identified but gave further insight into the transactions between the sender and Nelson & Sons.

7. George Brown’s signature

7. George Brown’s Signature: In 1896 Nelson & Sons decided to invest several substantial sums which were guaranteed by an American investment firm. Their correspondence with the American firm was directed to a Mr. Stewart Tods and concerned the investment of two separate sums of more than 10,000 dollars each. The letter, though entirely concerned with business, reflects the genial nature of professional signatures from the time. Here George Brown, a manager at Nelson & Sons, signs ‘Believe me, Yours Faithfully’. Though the letter concerns references to significant sums of money and is a reflection of a transaction, the signature is incredibly genial and far more affectionate than would be used in the same manner of business today.

8. Nelson & Sons employed a vast number of employees who all were integral to discovering, creating, and marketing literature. From travel writers to leather testers, Nelson & Sons often employed numerous professionals to vet their literature including Jane Macgregor and Jane Borthwick. Though each women worked with the company under other supervisions at various periods, Jane Borthwick was a translator of German hymns as well as a writer of English hymns, a collection of letters in this archive reveals that these two women were also engaged as test readers for the manuscripts sent to the company. Many of the letters sent by Borthwick and Macgregor reference literature they have been sent which contains female protagonists, from which it could be inferred that Nelson & Sons were recruiting female employees for female driven literature.

The Thomas Nelson collection (Coll-25) on our online catalogue: https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/resources/85801

On trial: digital collections relating to the slave trade and slavery in the West Indies

*The Library has now purchased access to the collection ‘Slavery: supporters and abolitionists, 1675-1865 ’. See New to the Library: Slavery: supporters and abolitionists, 1675-1865*

Thanks to a request from staff in HCA the Library currently has access to two digital archive series from British Online Archives relating to the slave trade in the West Indies, Running the West Indies: British records from West Indian countries under colonial rule and The trade in people: The slave trade in Africa and the West Indies.

You can access these digital resources via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 17th March 2019. Read More

On trial: Archives of Sexuality & Gender

*The Library has now purchased access to Archives of Sexuality & Gender. See New to the Library: Archives of Sexuality & Gender*

Thanks to a request from staff and students in HCA the Library currently has trial access to the Archives of Sexuality & Gender from Gale. This fully searchable digital archive spans the 16th to 21st century and is the largest digital collection of primary source material relating to the history and study of sex, sexuality and gender.

You can access this digital resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 18th March 2019.

Archives of Sexuality & Gender include documentation covering social, political, health and legal issues impacting LGBTQ communities around the world, as well as rare and unique books on sex and sexuality from the sciences to the humanities, providing a window into how sexuality and gender roles were viewed and changed over time. The types of documents covered include periodicals, newsletters, manuscripts, government records, organizational papers, correspondence, posters, books and other materials. Read More

Celebrating 100 years of Social Work at Edinburgh University

Welcome to the introductory blogpost of Advisors, Advocates & Activists: A Century and more of Social Work in Edinburgh.

Work has now begun on cataloguing the collections of Edinburgh University’s Social Work Department and the papers of associated individuals, including former staff. This blog will keep you updated on the project’s progress and share some of the highlights. Alongside posts from the project’s archivist and research assistant it is hoped to have contributions from other individuals who have an interest in the material.

Please follow us on twitter @socialwork100

In the meantime you can read more about the project in the About Us section and more about the history of social work education and practice at the university and beyond at www.socialwork.ed.ac.uk/centenary.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....