Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

March 3, 2026

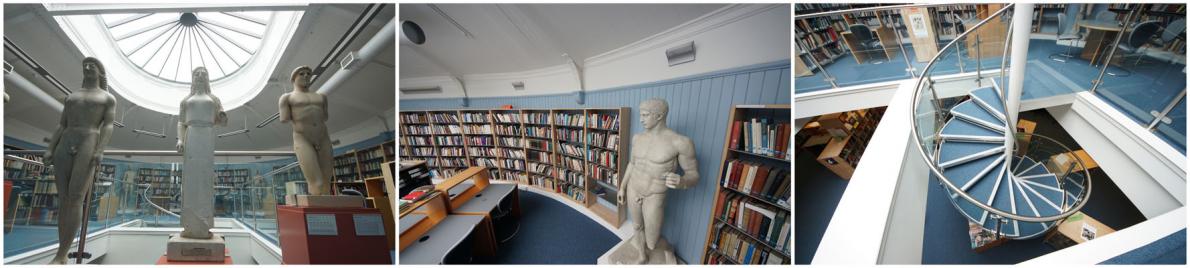

Library Tours for Staff 2024

Are you a new or exisitng staff member who would like to find out more about the University’s libraries?

Join an Academic Support Librarian on a 20 to 30-minute in-person tour of one of our ten Library sites. Find out about key library services, including EdHelp, borrowing, printing, and study spaces. Discover the general print collections at the Library and explore the subjects covered. Suitable for staff in all roles.

To book a tour, visit Event Booking.

Schedule of library tours:

Main Library

Main Library

17 January @ 14:00, 22 January @ 09:30, 6 February @ 10:30, 6 March @ 14:00, 2 April @ 10:30, 8 May @ 14:00, 12 June @ 14:00 (additional tours to be confirmed)

Art and Architecture Library

5 March @ 09:15

Edinburgh College of Art Library

18 January @ 09:15, 6 February @ 09:15, 9 April @ 09:15, 7 May @ 09:15, 11 June @ 09:15

Law Library

19 January @ 11:00, 12 February @ 10:00, 21 March @ 11:00 (additional tours to be confirmed)

Moray House Library

25 Jan @ 11:00, 22 Feb @ 11:00, 21 Mar @ 11:00, 25 Apr @ 11:00, 23 May @ 11:00, 20 June @ 11:00

Noreen and Kenneth Murray Library

Noreen and Kenneth Murray Library

14 Feb @ 15:00 (additional tours to be confirmed)

New College Library

30 Jan @ 16:00, 27 Feb @ 16:00, 26 Mar @ 16:00 (additional tours to be confirmed)

Royal Infirmary Library

26 Jan @ 10:00, 7 Feb @ 10:00, 26 March @ 09:30 (additional tours to be confirmed)

The Lady Smith of Kelvin Veterinary Library

24 Jan @ 14:00 (additional tours to be confirmed)

Western General Hospital Library

25 Jan @ 10:00, 19 Mar @ 12:30, 22 May @ 13:00

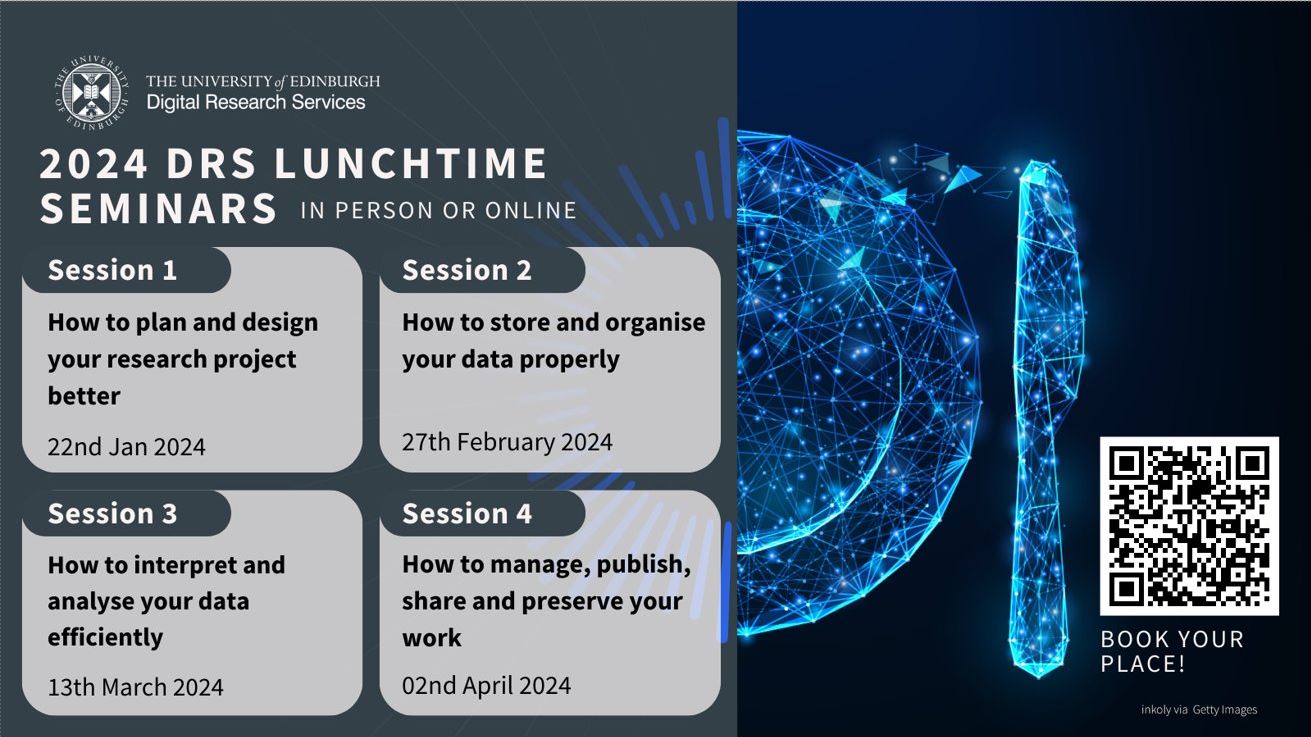

Lunchtime Seminar Series – digestible bites of knowledge on data and computing tools at the University of Edinburgh

For 2023/2024, Digital Research Services have organised a new iteration of the Lunchtime Seminar Series. These one-hour hybrid seminars will examine different slices of the research lifecycle and introduce you to the data and computing expertise at the University of Edinburgh.

The seminars have been designed to answer the most common questions we get asked, offering valuable bite-sized learning opportunities for research staff, postgraduate research students, and professional staff alike. You will gain an understanding of how digital research fits in with wider research support teams and good research practices. Your sessions will cover research funding, research planning, tailored skill development, data management and advancements in AI.

Oh, and did we mention there is free lunch for in-person attendees? That is truly the cherry on top.

DRS Lunchtime Seminars – 2024 Calendar

Have a look at the upcoming seminars:

Seminar 1: How to plan and design your research project better. 22nd January 12:00 – 13:00

This session is all about making sure researchers head off with a strong start. Did you know that the University has tools that help you optimise your data management plan, with funder specific templates and in-house feedback? We will make sure you get the best use out of DMPOnline and the Resource Finder Tool. We will also introduce you to some key concepts in data management planning, research funding and digital skill development.

Seminar 2: How to store and organise your data properly. 27th February 12:30-13:30.

Discover how to best store and organise your data using University of Edinburgh’s tools: DataStore, DataSync and GitLab. If you work in a wet lab, you might be particularly interested in electronic lab notebooks. We will introduce you to the functionalities of RSpace and protocols.io. Finally, the University has just launched an institutional subscription to the Open Science Framework (OSF). You will discover that it is much more than a tool for data storage, as it can help manage complex workflows and projects as well.

Seminar 3: How to interpret and analyse your data efficiently. 13th March 12:00-13:00

This seminar is mainly about big computers, such as UoE’s Eddie and Eleanor. Through EPCC, researchers can get also access to large scale national supercomputers, such as Archer and Cirrus. At the same time, we will show a glimpse on some developments on the AI front.

Seminar 4: How to manage, publish, share and preserve your work effectively. 2nd April 12:00-13:00

The final seminar is all about making sure your work is published and preserved in the best way. We will talk you through different (open access) publishing pathways such as Journal Checker, Edinburgh Research Archive, Read & Publish journal list, Edinburgh Diamond. We will also be talking about data repositories (e.g. DataVault, DataShare) and our research output portal, Pure.

For info and booking:

https://digitalresearchservices.ed.ac.uk/training/drs-seminars

Blog post by Dr Sarah Janac

Research Facilitator – The University of Edinburgh

New E-resources Trials

The Library has two new E-resources Trials running following requests from staff in HCA, ProQuest Historical Newspapers: ABC (1903 – 2010) and Codices Vossiani Latini Online.

Trial access to both databases ends 11th February 2024. You can access these two databases via the E-resources Trials page.

ProQuest Historical Newspapers: ABC (1903 – 2010)

Charles Lyell’s archaeological specimens at the University of Edinburgh

Will Adams completed his MA Archaeology dissertation at the University of Edinburgh Summer 2023 looking at Lyell’s archaeological specimens – achieving an impressive 78% and winning an award to boot! Read on to find out more about his spectacular findings…

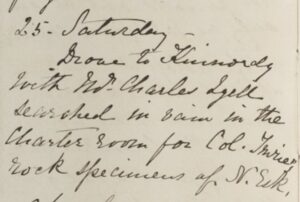

Scientific Notebook 266 page 14

Many specimens from Charles Lyell’s private collection were donated to the University of Edinburgh in 1927 and came directly from his family home and birthplace of Kinnordy House. In the very last Scientific Notebook, number 266, dated 17 July-23 November 1874, Lyell, in advancing age, is driven to Kinnordy to search “in vain in the Charter Room for Colonel Imrie rock specimens of N. Esk”.

This indicates that any finding aids to access what must have been a voluminous personal collection, even during Lyell’s lifetime, were problematic. No detailed documentation about the specimens at the time of the gift in 1927 appears to have survived, and the absolute authentication as having been part of Lyell’s specimen collection, is reliant on the existence of original labels. Subsequent use by staff of the University also had an impact on the specimens – a split occurred in the collection, with specimens now held by both the Cockburn Geological Museum and the Vere Gordon Childe Collection.

This paper is a study of the archaeological flint tool, VGC1363, held in the Vere Gordon Childe Collection and shows how it can be irrefutably reunited with Lyell through studying the object alongside his printed publications and recently acquired notebooks. This work highlights how an interdisciplinary approach utilising archive, library and museum evidence is essential for provenance research in scientific collections.

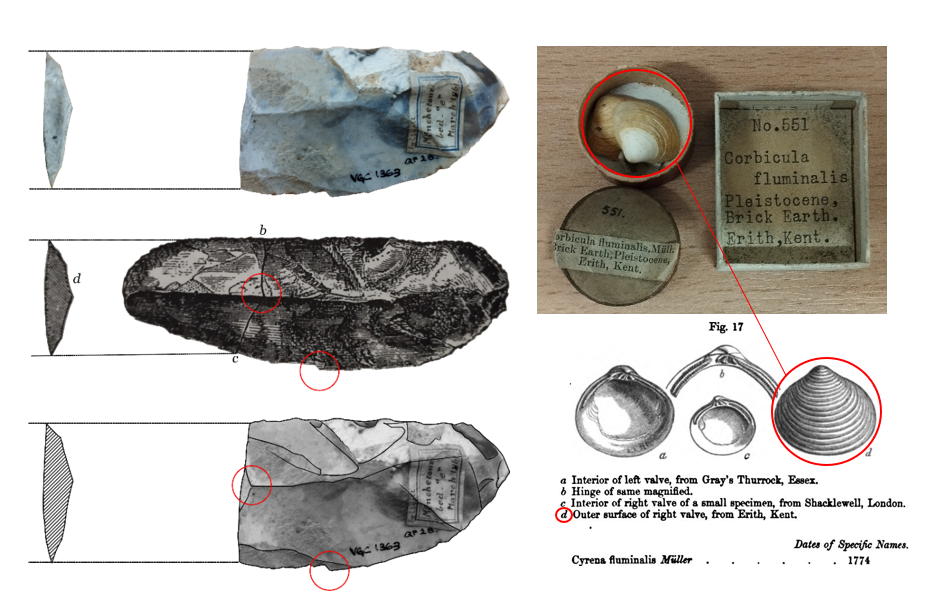

Figure 1. Illustration by Adams (2023) showing a match of specimen EUCM.0001.2022 with a figure in Lyell’s The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man (1863) realised by Dr Gillian McCay, Curator of the Cockburn Geological Museum

Using Lyell’s books as source material, Gillian McCay, Curator of the Cockburn Museum had confirmed that specimen reference EUCM.0001.2022, in Figure 1, had been ‘figured’ and included as an illustration in Lyell’s last major work, The Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man (1863), which had huge public success with almost all of the 4000 copies sold in its first week of publication (Cohen, 1999, 90).

Looking at the rest of the collection, I was intrigued to find out if I could reveal any more, and was particularly interested in a set of flint hand axes in a draw labelled “Misc. French Flints” in the Vere Gordon Childe Collection, that have ‘Sir C Lyell’ written directly on them or on the object label.

VGC1363: An indication of Lyell

Collecting evidence was critical for Lyell – surely more specimens could be found and identified, using his books? From developments in the human antiquity debate by Joseph Prestwich and John Evans in 1859, Lyell conducted his own research in the Somme Valley to provide an authoritative judgement.

Figure 2. Page 118 Antiquity of Man

Figure 2 shows page 118 of Lyell’s Antiquity. Studying this page carefully and using my knowledge of archaeological illustration I could see that this flint tool displayed in Lyell’s “Fig 14” has been broken in half from the “b” and “c” line in the original illustration and the section shown at “d”. Out of all the miscellaneous French flints in this draw, I could now narrow down my search to broken flint tools to provide a positive match.

Figure 3. Photograph by Adams (2023) of a drawer in the Vere Gordon Childe Collection labelled as “…Misc. French Flints” with specimen VGC1363 highlighted by a red circle

The flint tool circled in Figure 3 is broken in half, making it a candidate. It is fortunate to retain its label which reads “Sir C. Lyell, Menchecourt bed – ‘e’, March 1861” this connects it to Lyell. The connection is further supported by Lyell’s description of “Fig.14” as being a flint knife from Menchecourt (Lyell, 1863, 118).

Figure 4(a): Illustration by Adams (2023) comparing VGC1363 with “Fig.14.” through correspondence points; and on the righthand side Figure 4(b): Illustration by Adams (2023) showing a match of the specimen of Cyrena (Corbicula) fluminalis, EUCM.0222.2023, from Erith, Kent to illustration “d” in “Fig.17” of …Antiquity of Man (1863)

Furthermore, the illustration in Figure 4(a) shows how the object matches morphologically to Lyell’s “Fig. 14.”, through the transverse section and from the front view of the object.

This is an important object because of its context of being found “below the sand containing Cyrena fluminalis, Menchecourt, Abbeville” (Lyell, 1863, 124). Later in the book, Lyell goes on to explain that Cyrena (Corbicula) fluminalis is now an extinct species of freshwater shell in modern Europe, suggesting that the presence of a human modified flint tool in a stratigraphic layer below this shell supports human antiquity (Lyell, 1863, 124).

In Figure 4(b) a specimen of Cyrena (Corbicula) fluminalis held in the Cockburn Geological Museum collection appears to match the illustration and place name description of “Erith, Kent” typed in the extant label, in illustration “d” in “Fig.17.” of Antiquity of Man (Lyell, 1863, 124).

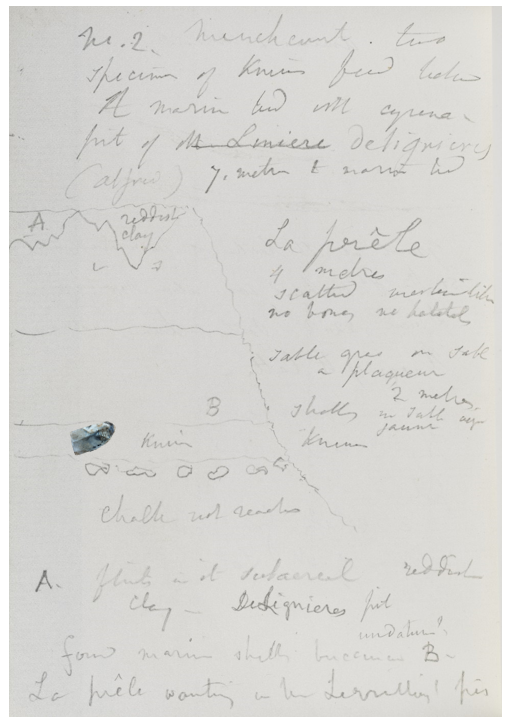

Turning away from the source material of books, and object labels – I was also able to consult Lyell’s rich archive, including the 294 notebooks. Knowing the time frame, and location I was able to establish that Lyell’s Notebook 245 records him being on site in Menchecourt in March 1861.

Figure 5. Figure 5: Edited photograph taken by Adams (2023) of Lyell’s notebook showing the flint knives place in the stratigraphy with a photograph of VGC1363 superimposed into the stratigraphy.

Figure 5 shows an edited version of Lyell’s stratigraphic drawing during his time there, showing flint knives found below a layer containing Cyrena (Corbicula) fluminalis. Lyell’s note at the top of the page 138 reads “Menchecourt. Two specimen of knives found below a marine bed with cyrena” which is the conclusive proof placing Lyell at the right place and time to uncover VGC1363.

Figure 6. Figure 6 The six archaeological specimens from University of Edinburgh conclusively connected to Charles Lyell. From top left to bottom right: EUCM.0001.2022; VGC1363; VGC1368; EUCM.0311.2009; VGC0860; VGC1366 (Adams, 2023)

Lyell’s specimens confirmed

Through my 4th year MA Archaeology dissertation, I conclusively identified another five archaeological specimens in the University of Edinburgh’s collections, shown in Figure 6, as belonging to Charles Lyell, and, through archival research, was able to create detailed object biographies for each. Although there are more flint hand axes with Lyell’s name attached which have not yet received the same detailed analysis, the trends seen in the object labelling system of the six specimens are consistent with the others in the collection. This makes it highly likely that the ‘Sir C Lyell’ labelled hand-axes in the Cockburn and Vere Gordon Childe collections belonged to the private collection of Lyell. An interdisciplinary approach was essential for determining the provenance of all six of these specimens – I had to apply both my archaeological knowledge and skills as well as newly acquired archival skills such as palaeography to fully understand what I was seeing. Piecing together this information was further complicated, due to a lack of relationships created between the different collections. As I embark on my working career, I’ll definitely advocate for establishing relationships between archive, museum and library catalogue entries to avoid a loss of provenance and the dispersal of materials.

Thank you, Will, for all your efforts – you should take great satisfaction for your part in identifying and repatriating a set of ‘miscellaneous French flints’ as being crucial to Lyell and his role in the Antiquity of Man debate, from which all future users will benefit!

Further reading

Cohen, C. 1998. Charles Lyell and the evidences of the antiquity of man. Geological Society Publications 143, pp. 83-93.

Lyell, C. 1863. The Geological Evidence for the Antiquity of Man (3rd Ed). London: John Murray.

Who Made the MIMEd 4477 Double Manual Flemish Harpsichord? (Part1)

In the first post of this two part series, our Musical Instrument Care Technician (and former conservation intern), Esteban Mariño Garza, discusses his Musical Instrument Research and Documentation Internship project to try and discover who made one of the harpsichords in the Musical Instrument Collections of the University. Read More

New Open Research Tool: Open Science Framework

Awesome news! The Research Data Service has a fantastic new addition to its Open Research toolbox! Fresh from the Centre for Open Science (COS) comes our institutional membership to Open Science Framework (http://osf.io): a powerful tool for supporting staff and students at the University of Edinburgh.

OSF is a free, open platform that provides full integration and sharing across the entire data lifecycle. Among many other things, it streamlines workflows with customisable project organisation and automated version control. It also enhances collaborative research, making it easy to find and connect with other UoE users and their research projects. But wait, there’s more! OSF enables easy management of private and public aspects of a project, so sharing with project teams as well as the wider research community couldn’t be simpler; it’s ideal for sharing preprints and preregistered reports. Best of all, with centralised storage for documents, data, and code, it eliminates the need to scramble around hunting for that one file you need right now: no more trawling through email chains to recover lost data!

To launch the new platform we’ve been running Free Lunch Lunchtime sessions, with Free Lunch in the Main Library. The Centre for Research Collections were kind enough to let us use their rooms on the 6th floor, so obviously, all our attendees used the stairs and worked up a proper appetite for their Free Lunch.

The first event was held on August 30th to a packed house, or room. After the Free Lunch and a bit of professional mingling, Gretchen Gueguen from the Centre for Open Science Zoomed in to give us a brief introduction to and overview of OSF: what it is, how it works, and why it’s such an excellent addition to any research toolbox. Gretchen was followed by Emma Wilson, PhD student, UoE representative for ReproducibiliTea, and Open Research Intern extraordinaire. Emma provided the first of two user-perspectives, talking about her experience of using OSF for her projects, presentations, and posters. The second pair of boots on the ground belonged to Mark Lawson, Data Governance Manager for the Childlight project currently being run out of Moray House School of Education and Sport. Being another long time-user of OSF, as well as being a fan of such tools, Mark spoke with great enthusiasm about the use of OSF to support the data management and project management aspects of his work.

Emma Wilson presenting during the OSF introduction event in August.

The second event wasn’t quite as packed as the first, but it was still nice to see those who managed to make it through the December wind and rain. Once again, Gretchen was there to provide the introduction and overview; and Emma, likewise, returned to talk about her experience as an OSF user. This time, the afternoon was rounded off by Gillian Currie who outlined the OSF training she and Eirini Theofanidou were ready and able to deliver. Before the close of the session Gillian had secured several bookings for her training sessions. Sadly, and despite having organised the event – and the Free Lunch – RDS won’t receive any commission for these bookings.

However, we will soon be in vigorous competition with Gillian and Eirini because we’re preparing to offer OSF Winter and Summer Schools. These sessions will be delivered remotely by COS to an in-person cohort of researchers over two or three days. If all goes to plan, we may even be recording the session recordings for future use. And yes, in case you’re wondering, there will, once again, be a Free lunch for attendees.

To learn more about the University OSF membership go to: https://edin.ac/47aGU0S. Questions about OSF? Email us: data-support@ed.ac.uk.

Dr Simon Smith – Research Data Support Officer

Research Data Support, Library & University Collections

Lingerie, Giant Frisbees and Heavy Lifting: Tackling the ITI Collection at Edinburgh University

By Abigail Hartley, Appraisal Archivist and Archives Collections Manager

ITI prior to processing, totalling over 70 linear metres of material

Several months ago, my colleague Jasmine Hide and I wrote two introductory posts about our new roles and what they entailed. This time, I would like to draw attention to a collection we recently appraised, that of the Information Technology Infrastructure, or, in its condensed form, ITI.

Now, it is no secret that – aside from our crucial Digital and Web Archivist team members – most archivists are not experts on the early history of computing. Having said that, for sixty years Edinburgh has prided itself on its forward-thinking approach to IT, particularly artificial intelligence. This is therefore an important collection that needed processing.

Arriving from the Department of Computer Science in 2017, the collection contains material that shows the development of the Edinburgh Regional Computing Centre, as well as the development and implementation of large-scale computing projects, services, applications, and programs from 1966 up to around 2000. It will be of particular interest to anyone researching the development of computing science, both as a practical feature in people’s lives, as well as the academic field.

Student Research Rooms in HCA

Today’s blog post is a guest post from Clare Wilson, SRR Co-ordinator, about the superb book collections available to staff and students from HCA in the Student Research Rooms.

Here at Edinburgh University in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology (HCA), we are fortunate to have the Student Research Rooms (SRR). This is a busy study space that is home to ten book collections. These collections have been bequeathed by important figures in HCA’s history and are continuing to grow.

Among the individuals who have made valuable donations is Jim McMillan, a previous Head of School. As a European historian and researcher of modern French history, he was a pioneer in women’s and gender history. The SRR is also home to the Sellar and Goodhart collection, named after two of Edinburgh’s most influential Classics professors. The Jim Compton collection is an American History compendium of some 2,000 books and boasts some of the only known copies of publications of its kind in Scotland. Read More

Women in STEM studies and careers: Professor Beth Biller and Dr Mary Brück at the University of Edinburgh

Ash Mowat is one of our volunteers in the Civic Engagement Team. Ash has been looking into the career paths of two women in science: Professor Beth Biller, currently Professor at the Institute for Astronomy, part of the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Edinburgh, and Dr Mary Brück, previously a principal scientific officer at the Royal Observatory Edinburgh.

The aim of this blog is to explore the work of two women astronomers with links to the University of Edinburgh. Firstly Professor Beth Biller, currently in post at the Royal Observatory, and also an earlier pioneer Dr Mary Brück who was first a postgraduate student and later teacher here from the 1940s onwards. In doing so we’ll explore the historic and current levels of obstacles facing women accessing studies and careers within the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields.

Introducing Professor Beth Biller

(Image above courtesy of footnote 1 below)

Professor Beth Biller is a Professor, previously Chancellor’s Fellow, at the Institute for Astronomy, part of the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Edinburgh. According to her biography on the university’s website, her research interests centres around direct imaging detection and characterization of extrasolar planets and brown dwarfs.[1]

Professor Biller was part of the research team on the recent observations from the James Webb telescope surrounding the atmospheric features elements detected on Planet VHS 1256b, some 40 light years away from earth.[2] Professor Biller commented “There’s a huge return on a very modest amount of telescope time. With only a few hours of observations, we have what feels like unending potential for additional discoveries”.

These exciting early findings were also further covered on the BBC and elsewhere.[3] Further information on the James Webb telescope can be found here. [4]

Professor Biller kindly consented to answer a few questions to give a fascinating insight into her early childhood interest in the planets and journey from education into her current work and areas of interest.

Q1: Can you recall from childhood when you first experienced an enthusiasm for any STEM subject and what these were?

Oh, very early on for me — I was fascinated by the planets in our solar system when I was 5 or 6 years old, especially the fact that Venus has thick cloud cover with sulphuric acid rain!

Q2: During your school education were you aware of differing expectations placed on boys and girls in terms of their being encouraged to choose STEM subjects and of their actual or predicted academic achievements in these?

I wasn’t consciously aware of differing expectations, but I do think such expectations affected what academic subjects I was encouraged to pursue. I was good, but not spectacular at maths, but quite strong in humanities subjects. I found that I received more encouragement for pursuing a humanities degree than a science degree, since I wasn’t an obvious “math whiz”.

Q3: When were you first drawn to astronomy, what sparked it, and how long did it take for you to decide to study this at University?

I was very interested in astronomy as a small child, then in school found myself channelled more into the humanities (for the reasons described above). When I was in high school, the first extrasolar planets were detected — and I pretty much decided at that point that astronomy was what I wanted to study, even if I wasn’t “good at maths”. However, what I’ve discovered since then is that mathematics, like so many other things, is a learned skill — and practice makes perfect.

Q4: What was your experience like at University both in terms of the course structure and teaching, and the general experience as a student?

I had a very different student experience compared to students at large Universities like the University of Edinburgh.

I went to a “small liberal arts college” in the United State, which is a type of institution that simply doesn’t exist in the UK — a very small undergraduate degree-granting institution with only 1600 students. My initial degree was in Astrophysics. An undergraduate degree in any strand of physics is intense. To be honest, pursuing my undergraduate degree was more intense and stressful than my PhD or working in the field has been.

Q5: Can you please tell us a little about your areas of specialisation in your astronomy work currently, and why they are so compelling?

I work on direct imaging of exoplanets, in other words, removing starlight to be able to produce images of planets hiding in the glare of their stars. Right now, this technique is only possible for young, high-mass planets e.g. analogues to Jupiter, but caught right after they have formed, so they are a lot hotter and brighter than Jupiter. The planets I study right now have cloud-top temperatures of ~1000 K, similar to a candle flame, and clouds made up of very fine particles of silicates. This means these are very not-habitable planets. However, all the techniques we are developing now can be applied to image rocky habitable zone planets around stars similar to our own Sun in future decades. Direct imaging is the likely method by which we will discover the first true Exo-Earth twin — i.e. a 1 MEarth planet orbiting at 1 astronomical unit from a star with a similar mass as our Sun.

Q6: What has been your experience of the James Webb telescope and its future potential, and is there still valuable exploring to be done with others such as the very large telescope? Also what will new developments like the extremely large telescope add to what the James Webb is providing?

JWST is amazing! It is performing extremely well and it looks like it may have a 20+ year lifetime. I’ve been very lucky to be the co-PI of one of the JWST Early Release Science Programs. We’ve obtained coronagraphic imaging of a young exoplanet, spectra of a somewhat more widely separated planetary mass object, and coronagraphic imaging of a young, planet forming disk. All of the data have been absolutely superb, and in the spectroscopic data we are finding a veritable zoo of new spectral features that we have not been able to study previously from the ground. The upcoming extremely large telescopes will be very complementary to JWST — JWST lets us observe at wavelengths inaccessible from the ground (>5 um), while the ELTs will provide improved resolution and contrast, producing the first direct imaging detections of older and colder planets more similar to the planets in our own solar system.

Q7: What advice would you give to a child or young adult with a passion for astronomy who wants to learn more and improve their potential to study at university level?

Make sure to take maths and sciences Highers — and remember, mathematics, coding, and analytical skills are all things that can be learned through practice.

Q8: If you received an unlimited NASA or other budget to use, what would be your dream mission project to explore and why?

Oh, that would definitely be a successor telescope to JWST, with the potential to image and characterize Earth-like habitable planets!

Whilst the equal representation of women in STEM subjects is far from being realized, Dr Biller’s and many others examples are an encouraging indication of a positive momentum for change. The following recent BBC features describes substantive increases in the numbers of women entering STEM careers. [5] Furthermore the recent appointment of Dr Nicola Fox as Associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (the organisations head of science, and only the second woman to have held this role) demonstrates that the highest positions could and should be equally obtainable by anyone with the experience and expertise, regardless of gender.[6]

(Image of Dr Cordelia Fine above courtesy of footnote 7 below)

Dr Cordelia Fine[7], the Canadian author and philosopher of science and psychologist, has written several absorbing and brilliantly researched texts serve to dispel the myths of distinct male and female brains and exposes how restrictive gender constructs in how children are raised and not biology help precipitate reduced opportunities for women in STEM careers, and equally for men in more nurturing roles like primary school teaching. Dr Fine lived and schooled in Edinburgh before studying at Oxford and Cambridge, and won the Edinburgh Medal in 2018 for her work, and additionally won the Royal Society Science Book prize in 2017 for her book Testosterone Rex which includes the following: “Beyond the genitals sex is surprisingly dynamic, and not just open to influence from gender constructions, but reliant on them. There are no essential male or female characteristics”.

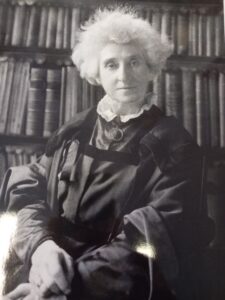

Dr Mary Brück Biography and University Archive materials

(Image above courtesy of footnote 8 below)

Dr Brück (nee Conway 1925-2008) was born in Ireland and became a STEM pioneer studying and later teaching in the fields of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of Edinburgh.[8] The Mary Brück building at the University of Edinburgh Kings Buildings campus was built in recognition of her academic achievements, research, findings and teachings, and as an empowering role model demonstrating the capabilities of women in subjects traditionally deemed only suitable for men. That she was active in delivering lectures and inspiring others well into her retirement and until near her death, is further evidence of her energy, resilience and highly valued expertise.

As well as becoming a senior lecturer Dr Brück continued research and published her findings academically, specialising in the area of stars, the interstellar medium and Magellanic Clouds. [9] She received the Lorimer Medal from the astronomical society of Edinburgh in 2001 for her extensive contribution in making the subject of astronomy accessible to and of interest to the widest audience, not solely to those in academia. She was further awarded a fellowship of Edinburgh University in 2005 at the age of eighty.

I was privileged to been granted access to some of her archive papers (as yet not catalogued) held at the University of Edinburgh Astronomy department on Blackford Hill. [10]

(Image of Dr Brück and colleagues at the Royal Observatory; she is seated in the front row fourth from the left).

It emerges very evidently from looking through her documents that Dr Brück was something of a polymath, with wider interests in sciences and mathematics, the visual arts, history, poetry etc. It seems clear that her lifelong academic passion was for astronomy, both in studying and teaching to bring her joy for the field onto others.

She devoted a lot of research and writing on the current and historic role of women in history, and early pioneer of women in STEM studies and careers.

The above Women in Astronomy Perspective event was both organised and introduced by Dr Brück. This is remarkable evidence of her energy and commitment in her chosen science well into her retirement, as she was into her seventies and continuing research, writing, events and public speaking.

(Image on the above left of earlier woman astronomer pioneer Lady Margaret Huggins[11] whom Dr Brück extensively researched and wrote upon to promote her achievements and legacy. Image on the right of an issue of Mercury magazine cover with a special focus on women in astronomy).

In her records there is much evidence of Dr Brück’s Christian faith and how she strove to dispel the lazy myth that there is any discrepancy or conflict between being both a practitioner of science and having religious faith and convictions.

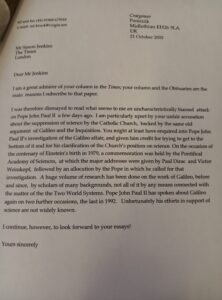

(The above letter refers to Dr Brück’s ongoing work on speaking to address the links between God and science).

A further interesting exchange on religion and science is revealed in the article below on the left, and Dr Brück’s letter of response. The article was a Times newspaper critique of the Pope John Paul 11. Dr Brück responded to rebuke the antiquated reference to Galileo and historic disputes between science and religion that she argues have since been bridged with better shared understandings. It is perhaps notable that she elects not to respond to the journalist’s comments on the Catholic Church’s attitudes on homosexuality, contraception and the scope for women to enter the priesthood, although her main focus of her short response was to emphasise her assertions on the coexistence of practicing scientific endeavours and a religious faith.

A fascinating find amidst her records is a handwritten series of 8 lectures on astrophysics that Dr Brück both wrote and presented to students. It includes such topics as methods of observation (the different types and sizes of telescopes and their uses and capacities), the properties and types of stars (mass, luminosity, temperatures etc.), interstellar matter and the relationships between bodies in our solar system and beyond.

(Image from lecture notes above on comparative star types and temperatures).

From the introduction to the series of lectures she writes:

“In the following series of lectures I shall attempt to introduce you to the subject of astrophysics which, I believe, represents one of the most active and promising fields of present day scientific research. Astrophysics is a very young subject. However it has grown so much already and it is growing so rapidly that all I can say here is to give you a genuine summary of the main procedures under discussion, of the methods of investigation, and of the results obtained so far.”

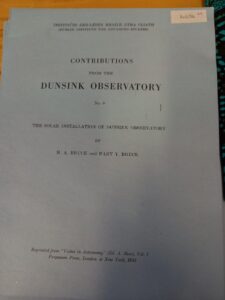

(Cover and image above from joint publication of Dr H.A and Dr Mary Brück)

In conclusion, it is abundantly evidenced in these archives that Dr Mary Brück was a formidable pioneer of women in science, and in her field of astronomy a passionate expert who sought to promote and teach the science to others, and who consistently strove to have recognised and valued the legacy of earlier women astronomers that preceded her. She tirelessly devoted a lifetime to her chosen academic field, continuing to pursue valuable research and lecturing roles well into her seventies and eighties. She should rightfully be celebrated as a major force in her academic achievements and teachings, and an early role model and inspiration to others for the opportunities and representations of women in STEM studies and careers.

Finally I should like to thank Professor Biller for finding the time to answer some questions on her areas of interest and expertise, with thanks also to staff at the University of Edinburgh Royal Observatory for kindly allowing access to view records from the Mary Brück archives.

(The two fellow Dr Astronomers: Dr Mary Brück and her husband Dr Hermann Brück)

[1] https://www.ph.ed.ac.uk/people/beth-biller

[2] https://www.ph.ed.ac.uk/news/2023/distant-planets-features-revealed-by-webb-telescope-23-03-22

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-65040983

[5] The women who left their jobs to code – BBC News

[8] https://www.ed.ac.uk/equality-diversity/celebrating-diversity/inspiring-women/women-in-history/mary-bruck

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....