Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

February 24, 2026

Food and drink in Scotland: Why Scots ate and drank what they did

The previous post on Scotland’s food and drink highlights the fact that what people ate was very much dependent on what people could grow, according to climate, topography and soil type.

In Kilbride, County of Bute, “the soil is hard and stony. Most of the farms lying on the declivity of hills, the best prepared land scarce yields two returns. To supply the deficiency of corn, the inhabitants plant great quantities of potatoes, which are their principal food for 9 months in the year.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 578)

In contrast, the soil in the parish of North Berwick, County of Haddington, was “, in general, rich, fertile, and well cultivated, producing large crops of all the different grains sown in Scotland, as wheat, barley, oats, pease and beans. No hemp is raised, and the quantity of flax is inconsiderable, being only for private use. Turnips are cultivated, but not to a great extent, as the farmers reckon the ground to be in general too strong and wet for that useful plant, and on that account commonly prefer sowing wheat upon their fallows. Potatoes are raised in considerable quantities, and, during the winter, form a principal part of the food of the poorer classes of the people.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 441)

Farquharson, David: The Banks o’ Allan Water, 1877. Photo credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

You can really sense from reading the parish reports that there was a real understanding of what crops could be successfully cultivated and how best to grow them. For example, in Ferry Port-on-Craig, County of Fife:

“The crops that are best adapted for the clay, to produce the greatest profit, are, wheat, beans, barley, grass, and oats. Flax is sown to very good advantage; but, on the whole, it is rather an uncertain crop; it likewise produces potatoes, but the quality is generally not so good as in light soils. The strong loam stands on a whin rock; and, where there is sufficiency of soil, it produces wheat, oats, beans, barley, grass and potatoes, in great perfection. Flax is sometimes sown on this soil, but seldom proves a good crop.” (OSA, Vol. VIII, 1793, p. 458)

In the parish report for Kinloch, County of Perth, several varieties of potatoes cultivated in that parish are mentioned, including the London Lady, the red-nosed-white kidney potato and the dark red Lancashire potato. Some advice is even given on “the best method of preventing potatoes from degenerating, and of rendering them more prolific”. (OSA, Vol. XVII, 1796, p. 472)

It seems that the widest range of produce was grown in the north of Scotland. In Unst, County of Shetland, the list of what was cultivated is very impressive:

“Black oats, bear, potatoes, cabbages, and various garden roots, and greens which grow in great perfection, are the most common vegetables in this island. Artichokes, too, of a delicate taste, are produced here, with some small fruit, and most of the garden flowers that grow in the north of Scotland. There is little or no sown grass, but the meadows are rich in red and white clover, and in the seasons of vegetation, are enameled with a beautiful profusion of wild flowers. The pasture grounds, in the commons, are generally covered with a short, tender, flowering heath. Some curious and rare plants have been discovered in this island by some gentlemen skilled in botany. The common people gather scurvy grass, trefoil, and some other plants that grow in the island, for their medicinal qualities. The roots of the tormentil are used in tanning bides.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 186)

Reay, County of Caithness, was another parish which produced “an abundance of all provisions necessary for the use of the inhabitants. The exports are in general bear, oatmeal, beef, mutton, pork, geese, hens, butter, cheese, tallow, malt, whiskey, to the market of Thurso; black cattle, sold to drovers from the south; horse colts, sent to Orkney; lambs, to the lowlands; geese, sometimes to Sutherland and Ross; as also hides, skins, goose-quills, and other feathers.” (OSA, Vol. VII, 1793, p. 575)

This knowledge extended to the preservation and transportation of food. One “adventurer” from the parish of Dyke and Moy, County of Elgin, “cured a quantity [of cod] in barrels, like salted salmon, carried them to London, and made no loss by the adventure, though they sold heavily, and must have been but unpleasant food. But had these cod been parboiled, and cured with vinegar at the boil-house, like kitted salmon, it is believed, such soused fish would have excelled the salted, as much as the kitted salmon exceeds the salted, in quality and price.” (OSA, Vol. XX, 1798, p. 209)

Selling of produce

In most cases, what was cultivated or reared by farmers was then sold in the large towns and cities. In the parish of New Machar, County of Aberdeen, its proximity to the city of Aberdeen was seen as a big advantage, as there was “a constant demand, ready market, and a reasonable price for every article which the farms produce.” However, it was also seen as a disadvantage, as it “renders every article sold within the parish, very high priced to those who must buy; and that the country people are so much in the way of attending the weekly market, that they generally lose one day in the week, in order to dispose of an article, which when sold, will scarcely bring them 1 s. 6 d. never considering the loss of time and labour”. (OSA, Vol. VI, 1793, p. 469)

Aberdeen Fish Market by Frederick Whymper, 1883. Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

As a result of growing and raising such produce, farmers themselves began to become more wealthy, as pointed out in the parish report for Cambuslang, County of Lanark:

“The farmer, as well as the merchant, came by degrees to relish the conveniences, and even the luxuries of life; a remarkable change took place in his lodging, clothing, and manner of living. The difference in the state of the country, in the value of land and mode of cultivation, in the price of provisions and the wages of labour, in food and clothing, between the years 1750 and 1790, deserves to be particularly recorded.” (OSA, Vol. V, 1793, p. 251)

However, not all farmers were so hard-working and successful! In a survey, carried out in 1778, it was found that the inhabitants of Auchterarder, County of Perth, were “idle and poor farmers not thinking it necessary to thin their turnip while small, allowing them to grow until they be the size of large kale plants, and then it is thought a great loss to take them up, unless in small quantities, to give to the cow. A few tenants excepted, no family had oat-meal in their houses, nor could they get any. The oat nothing better than bear-meal and a few greens boiled together at mid-day, for dinner, and bear-meal pottage evening and morning.” (NSA, Vol. X, 1845, p. 288)

Vocabulary

In an interesting aside, the peasantry in the parish Cross and Burness, County of Orkney, used “a good many words […] peculiar to the north isles, and some of them are evidently of Scandinavian origin.” Many of these words were farming and food-related. Here are the first few words given:

“Abin, (v.) to thrash half a sheaf for giving horses. –Abir, (n.) a sheaf so thrashed. –Acamy, (adj.) diminutive. –Bal, (v.) to throw at-Been-hook, (n.) part of the rent paid by a cottar for his land is work all harvest; but besides his own labour, he must bring out his wife three days, for which she receives nothing but her food. All the women on a farm are called out at the same time; they work together, and are called been hooks, and the days on which they work been-hook days. –Bull, (n.) one of the divisions or stalls of a stable. –Buily, (n.) a feast. –Buist, (n.) a small box. –Builte, or Buito, (n.) a piece of flannel or home-made cloth, worn by women over the head and shoulders. –Brammo, (n.) a mess of oatmeal and water. –Bret, (v.) to strut. –Brodend, (adj.) habituated to. –Burstin, (n.) meal made of corn parched in a pot or “hellio”…” (NSA, Vol. XV, 1845, p. 95)

(Look out for our posts on Scotland and its languages coming soon!)

Conclusion

It is clear that Scots in the countryside ate what they themselves produced, which was dependent on the climate, topography – and not forgetting knowledge and hard-work! Those in cities, such as Glasgow and Aberdeen, were able to buy this produce in markets. Increased knowledge, new technologies and the exporting of goods from other countries had seen the situation change for the better over the years.

In the next post on Scotland’s food and drink we will look at times of food scarcity, the provision of food as part-payment and the link between food and health as seen by those in the late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth centuries.

New Professionals – Skills Development

This blog post comes from one of our project volunteers, Daisy Stafford. Daisy made a significant contribution to the project in her work data cleansing retro-converted catalogue descriptions. As Daisy points out, this can be one of the more mundane archival tasks that can take up our time but equally an essential means to an end. We were delighted to have Daisy on board and thanks to her great work we are ever closer to that end. Thank you Daisy!

As a postgraduate student, working towards an MSc in Book History and Material Culture, there is nothing as invaluable as hands-on practical experience within your field. My course introduced the range of professional roles that surround working with special collections, but last summer I decided it would be useful to gain further experience within one particular collection. Having volunteered within the Lothian Health Services Archive (LHSA), I was on the lookout for any other relevant archival opportunities. My time with the LHSA had also focused my interest on access issues surrounding collections, particularly how administrative and cataloguing tasks can increase the visibility and facilitate the use of a collection.

Daisy’s work contributed greatly to enhancing catalogue descriptions and consequently access to many beautiful collection items. One such item is this frieze panorama of Paris; ink, chalk and colour wash by Adrian Berrington. 1914. (Ref: Coll-1167/A1.56A)

I was subsequently introduced to the Patrick Geddes project, and working with Project Archivist Elaine, I committed a half-day a week to help with a data clean-up task. Using Optical Character Recognition, the data had been retro-converted from an historic printed catalogue into an Excel spreadsheet, with varying degrees of accuracy. The majority of the information was there, but the order was very jumbled and needed manually re-ordered, checked, and tidied to become comprehensible and fit for transfer to the online archive catalogues. Consulting the printed catalogue, and occasionally undertaking my own research, I methodically checked the details for each item, correcting where necessary. I then split the data into separate fields which complied with the International Standard for Archival Description (ISADg): including but not exclusive to; title; date; creator; format; dimensions; scope and content etc. This work would eventually enable the application of Encoded Archival Description (EAD), which would transform the completed spreadsheet into a fully searchable online catalogue. In total, I cleaned over 363 catalogue descriptions. The prospect of increasing the access to and eventual use of this exciting collection is what motivated me through the occasionally monotonous data cleaning.

This task developed my previously non-existent archival cataloguing skills, teaching me to interpret, analyse and sort data, identify OCR errors and apply corrections, and generally increase my experience with Excel. It was also a supremely satisfying task for someone as committed to organisation and imposing order as I am. Overall, the experience may have dispelled any romantic notions I had of archivists spending their whole days looking at beautiful collection items, but it impressed upon me the importance of cataloguing tasks in the management of special collections.

An archivist looks at a beautiful collection item. Grant Buttars (University Archivist) discovers the print mock-up for the Pepler Cities Exhibition, London. 1948. (Ref: Coll-1167/A.8.3)

Since the end of my volunteering on the project, I completed a work placement at the National Museum of Scotland, where I was responsible for enhancing the catalogue records of the museum’s rare books collection. Although a very different cataloguing system, the Patrick Geddes project introduced me to the key data fields and showed me the level of detail necessary for this kind of work. It is an experience that will only increase in relevance as I progress in my career working with special collections.

On trial: Cold War Eastern Europe, 1953-1960

Thanks to a request from staff in HCA the Library currently has trial access to the digital primary source collection Cold War Eastern Europe, Module 1: 1953-1960, a unique and comprehensive, English-language history of post-Stalinist Eastern Europe. If you’re interested in East European and Soviet history, 20th century international relations, Cold War history or the history and culture of individual states within Eastern Europe then this database could be for you.

You can access this online resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 25th May 2018.

Cold War Eastern Europe provides full-text searchable access to over six thousand primary source files from the political departments of the UK Foreign Office, source entirely from The National Archives series FO 371. Files cover every aspect of political, economic, cultural, social and dissident life behind the ‘Iron Curtain’. Read More

Travelling Images: Venetian Illustrated Books 3

This week the exhibition curator, Laura Moretti, of the University of St. Andrews, writes about the finest, and probably most famous book in our selection: Andrea Palladio’s “Four Books of Architecture”.

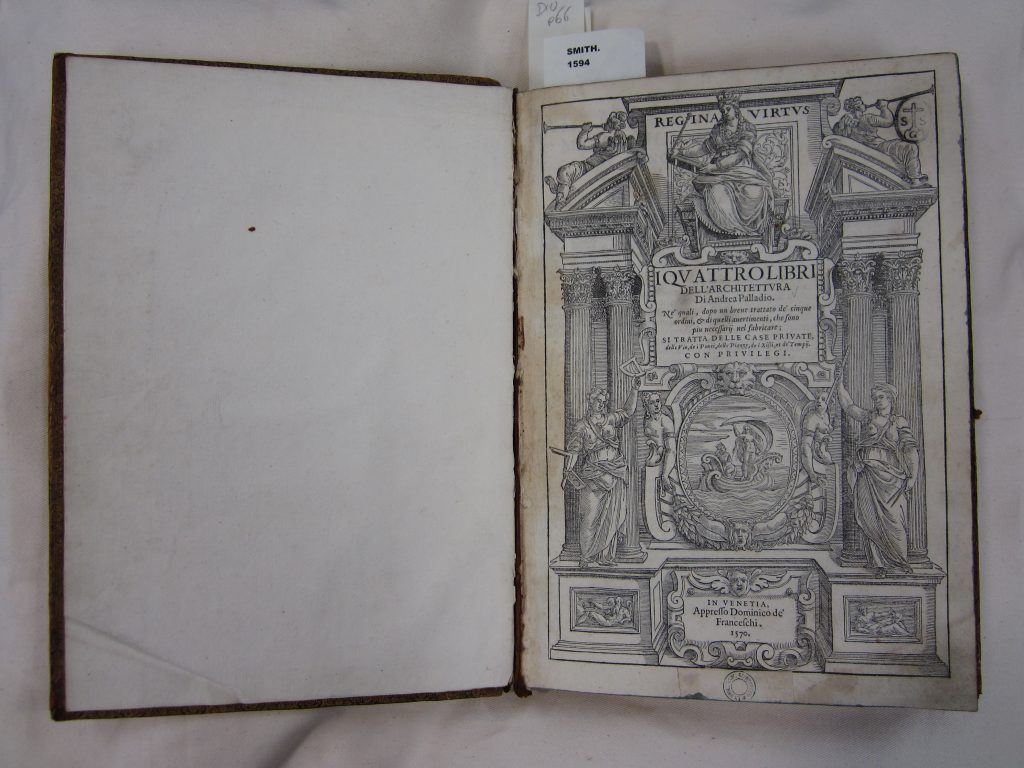

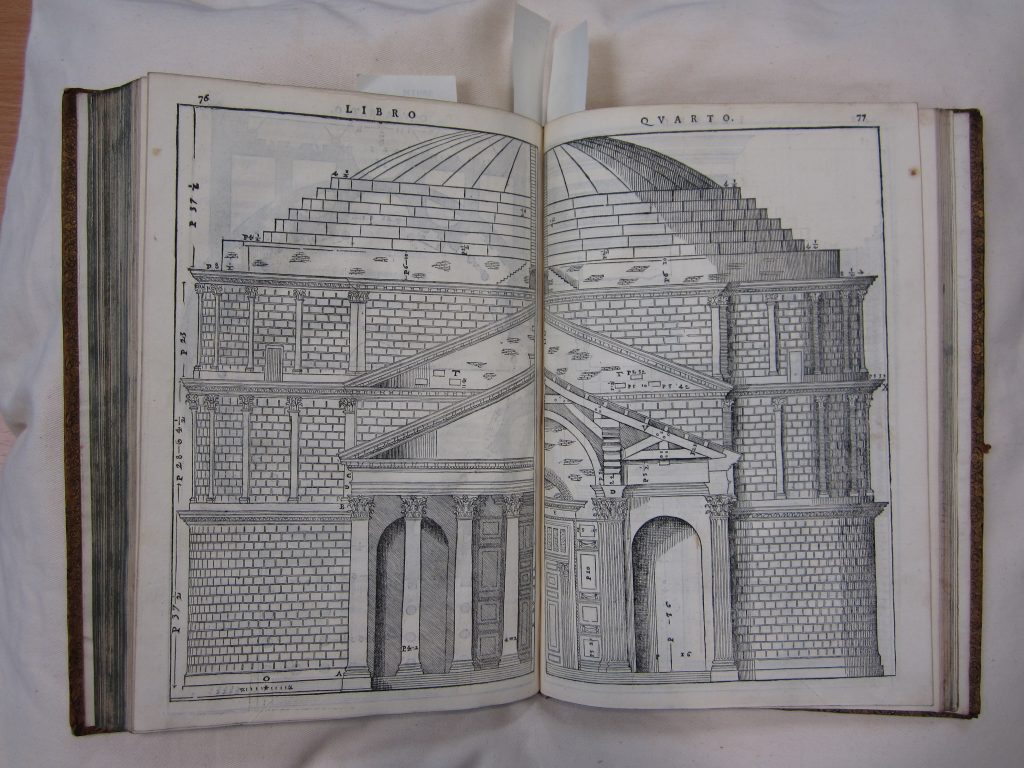

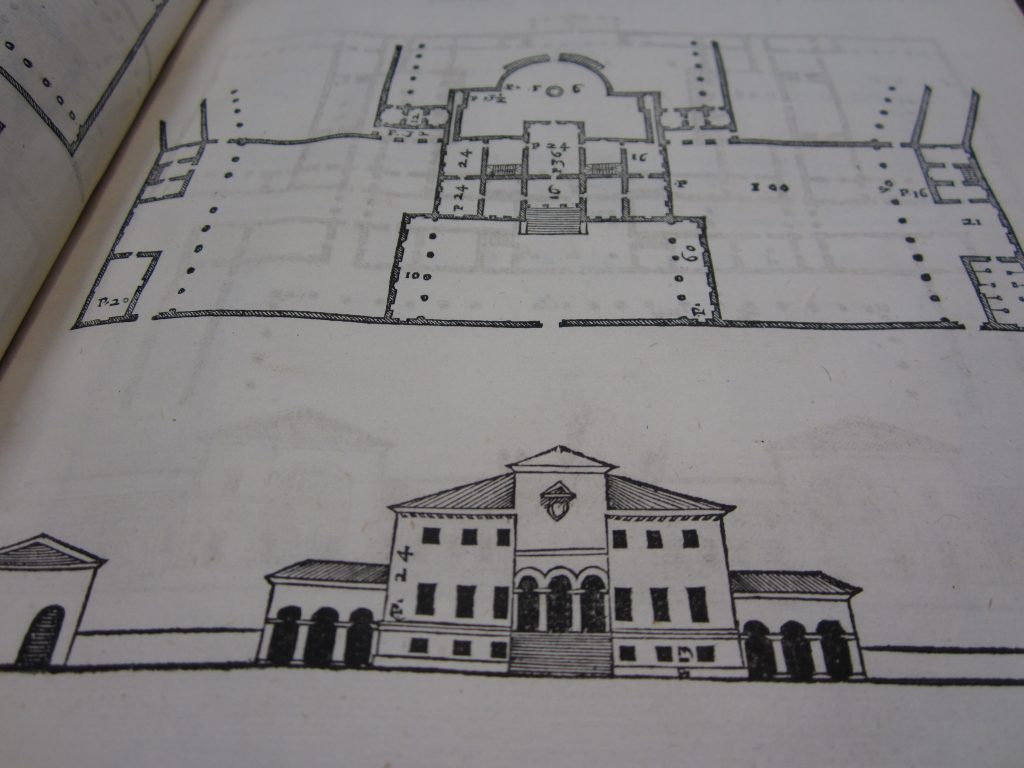

Andrea Palladio, I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, (Venetia: Dominico de’ Franceschi, 1570) (University of Edinburgh Library, Special Collections, Smith.1594)

Andrea Palladio (1508-80) first published his I quattro libri dell’architettura in Venice in 1570, in the printing shop of Domenico de’ Franceschi (fl. 1557-75), publisher and book dealer from Brescia, at the sign of “Regina Virtus” in the Frezzeria. The book enjoyed extraordinary fortune, through its numerous editions and translations, becoming the main channel of the widespread knowledge and appreciation of his author’s work.

Title page detail

Palladio already had important experience in the field of book publishing. In 1556, Daniele Barbaro – a refined and sophisticated Venetian patrician, and already the architect’s patron and supporter – put through the press a translation with commentary on the architectural treatise of the Roman author Vitruvio, complemented by Palladio’s lavish illustrations.

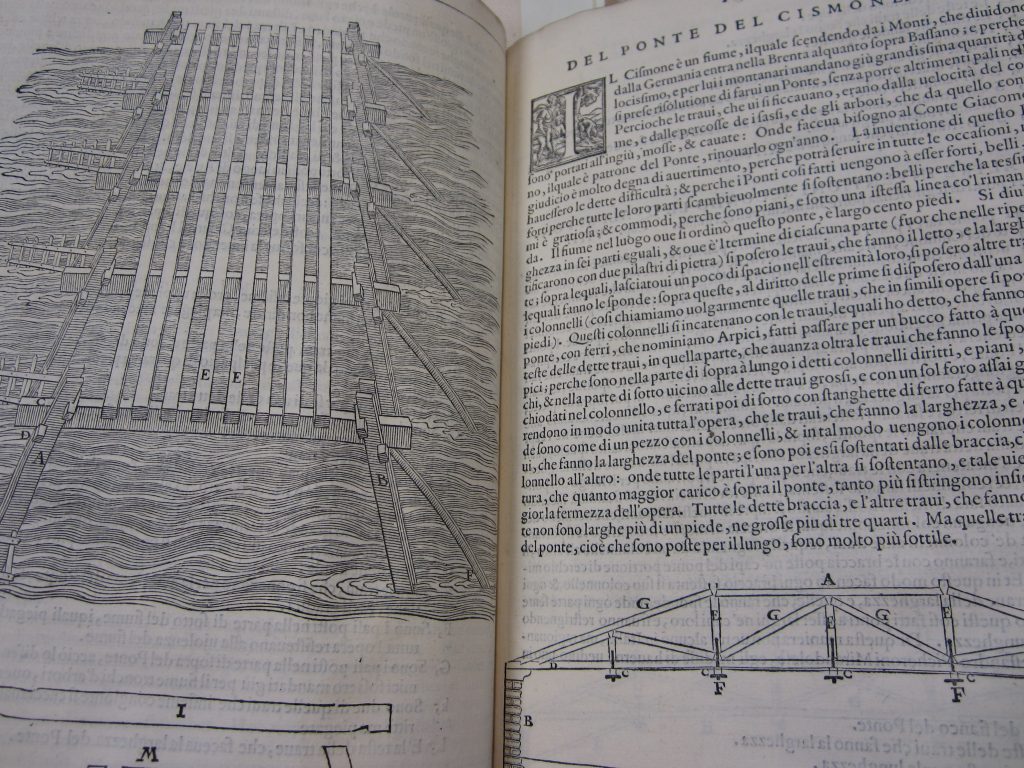

In Palladio’s treatise, the subject matter is subdivided in four sections: the first book – dedicated to a friend and patron, the Vicentine Count Giacomo Angarano – discusses the fundamental principles of building and the five architectural orders; in the second book Palladio presents his portfolio of projects for residential palaces and country houses, and reconstructions of ancient Greek and Roman houses; in the third book – dedicated to the Prince Emanuele Filiberto Duke of Savoy (1528-80) – the architect treats roads, bridges, squares, basilicas and other public buildings; while the fourth and final book is dedicated to antique temples in Rome and elsewhere, in the Italian peninsula and beyond. Book One, Book Three, and Book Four also contain introductory letters to the readers.

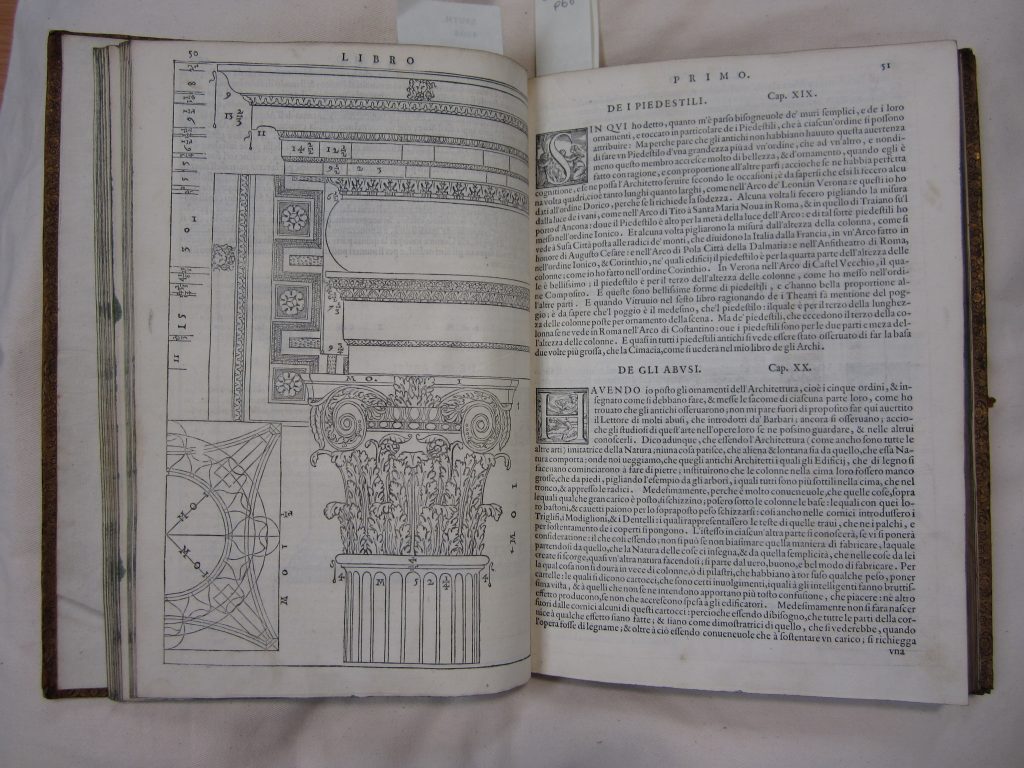

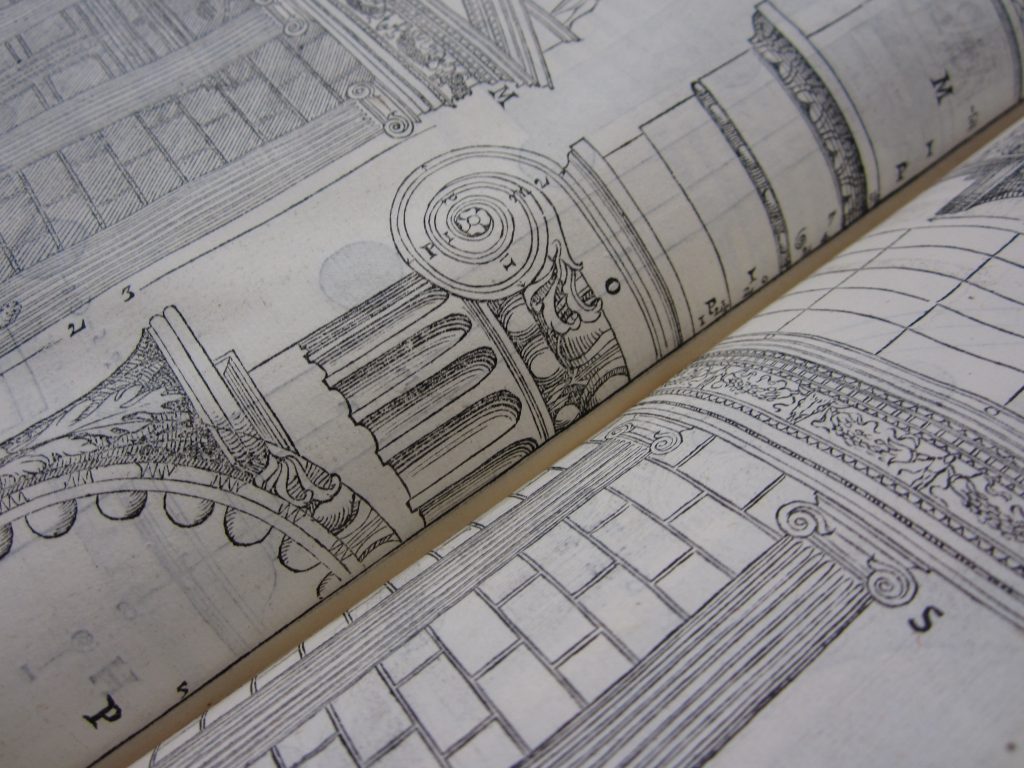

Book 1. The Composite Order

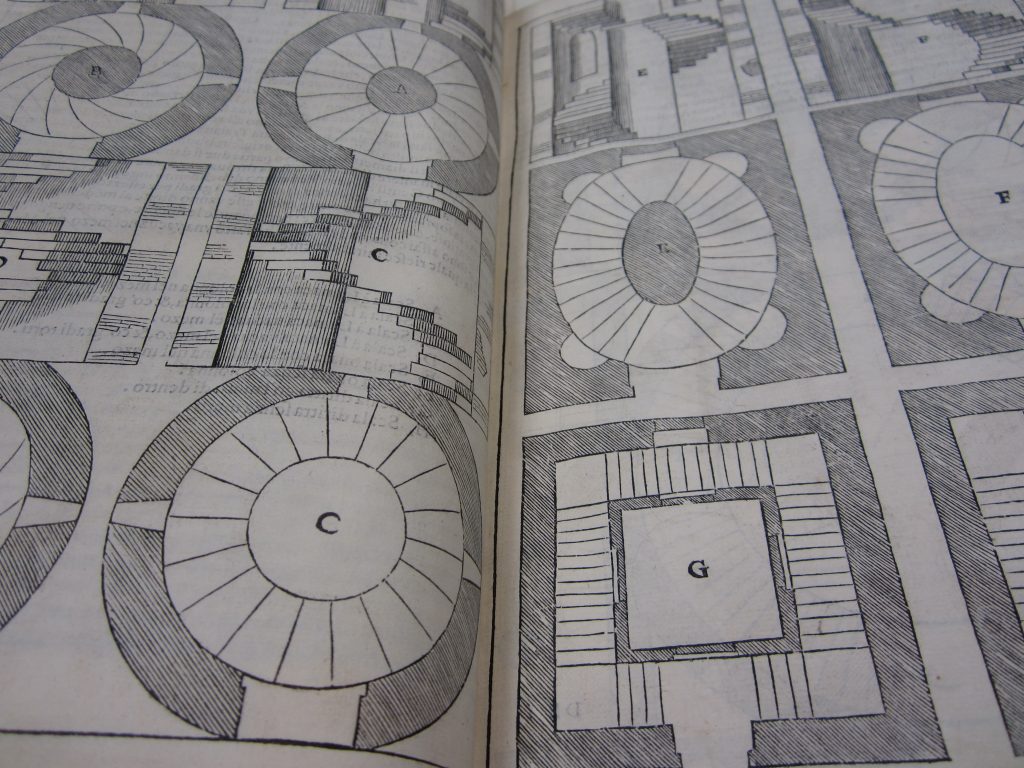

Book 1. Stairs

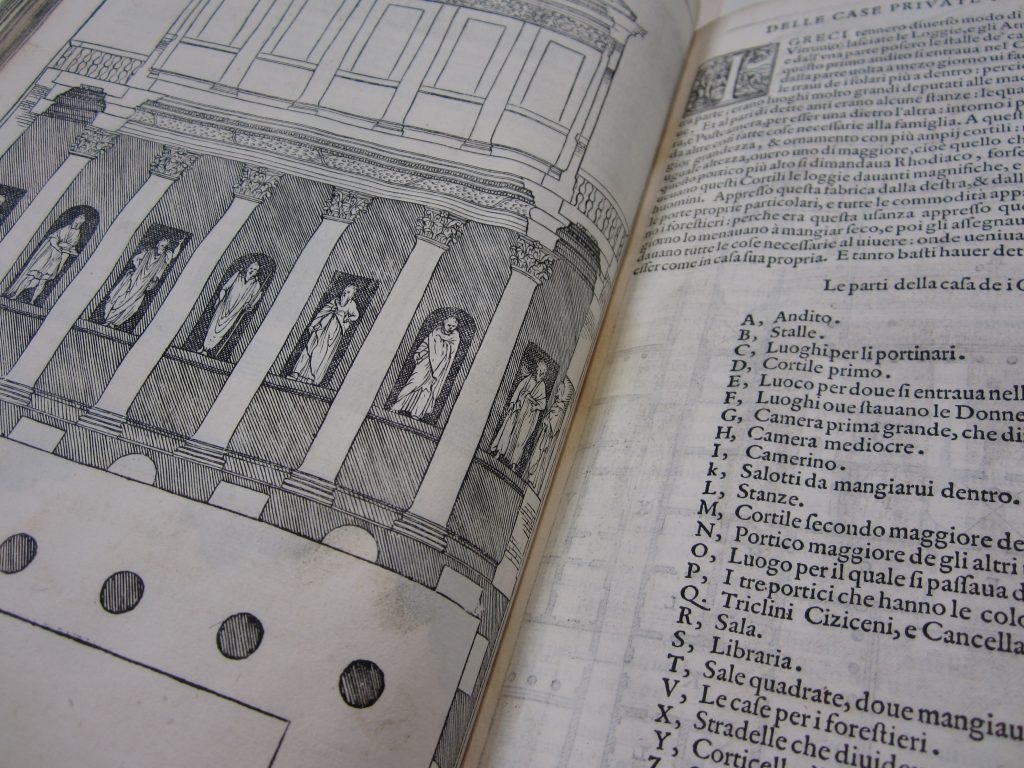

Book 2. House of the Greeks (detail)

Book 4, detail of the Temple of Portunus

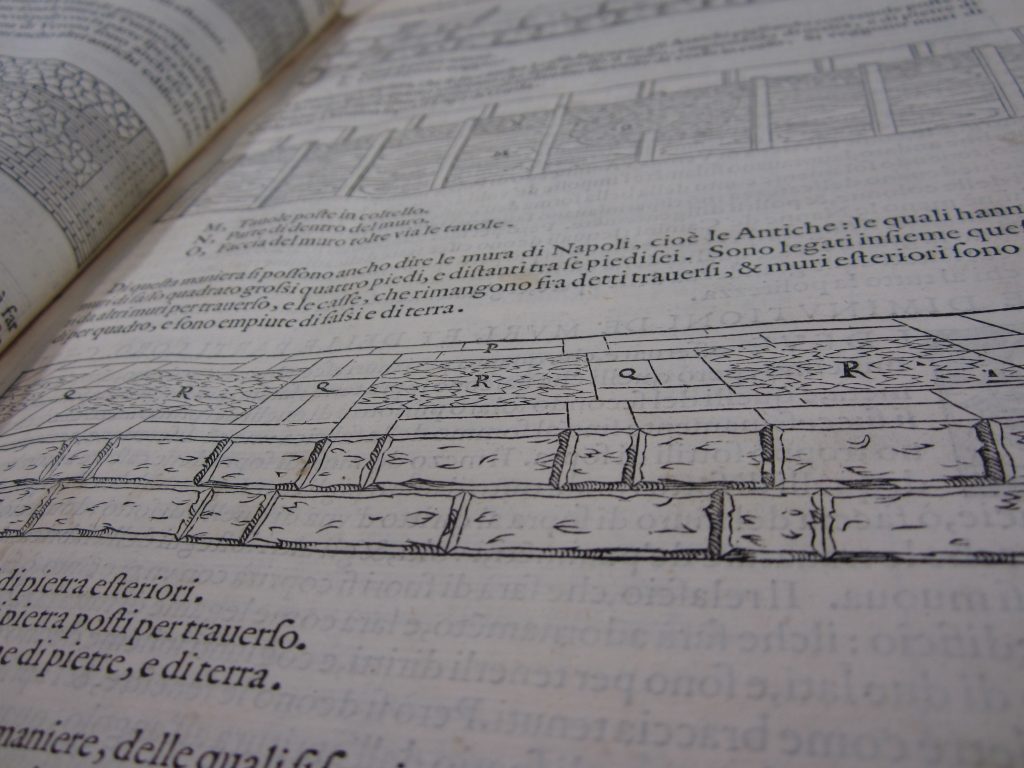

The edition is finely illustrated: all the books are introduced by a full-page woodcut and illustrated by numerous diagrams and architectural details. The relationship between words and image is heavily weighted towards the latter. The text is often used to explain and elucidate the drawings, and frequent lists referring to corresponding details in the illustrations provide precise terminology and further interpretations. The drawings frequently present measurements, which give a clear sense of the proportions between different architectural elements. Palladio very rarely makes use of perspective: the only exceptions are constituted by the description of brick courses and layers in Book One, and the representation of Caesar’s Rhine bridge in Book Three.

Book One, detail of brick courses.

Book 3. Detail of Caesar’s Rhine Bridge

The majority of the drawings are plans, elevations or sections, variously articulated in the page layout. Contextual elements defining the buildings’ surroundings are rare and limited to some schematic representations of water and occasional exemplifications of soil. Shadows are consistently employed to confer profundity to the architectural elements, from the depiction of minute details to the outlines of massive buildings. The potentialities of the medium are fully explored and used at their best.

Book 4. The Pantheon

While in the depiction of ancient buildings Palladio shows an obsessive attention to the accuracy and faithful rendering of detail, the representations of his design projects present elements of greater complexity. More than faithful copies of the completed buildings, they seem to be idealizations, perhaps the architect’s successive reflections or maybe the sign of ideas not fully executed.

Book Two, Villa Godi, Lonedo di Lugo di Vicenza

The copy now preserved at the University of Edinburgh comes from the library of Adam Smith FRSA (1723-90), the Scottish economist, philosopher and author, and a key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment era. The University of Edinburgh holds about half his original library (850 works in 1,600 volumes), including books on politics, economics, law and history, but also many literary works, particularly French literature, and books on architecture.

The full catalogue record for our copy can be found here: https://discovered.ed.ac.uk/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=44UOE_ALMA21147069860002466&context=L&vid=44UOE_VU2&search_scope=default_scope&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US

On trial: J. Walter Thompson: Advertising America

Are you interested in the social, cultural, and historical impact of advertising and marketing? If so, the Library currently has trial access to J. Walter Thompson: Advertising America from Adam Matthew Digital which may be just what you are looking for as it documents one of the world’s oldest, largest and most innovative advertising agencies.

You can access this online resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 14th May 2018. Read More

New College Library Steps Through Time – 23-25 April

Steps Though Time is a project to create a timeline of six display panels to be mounted up the steps into New College Library. This will tell the unique story of New College Library through images of six treasures selected from the library’s rare book, archive and object collections. These images will be set against a timeline of Scottish religious history with an Edinburgh focus.

Students, we want you to help choose the images for the panels! We will be displaying a selection of library treasures over three days in the Funk Reading Room for you to choose from. Read More

On trial: Secrecy, sabotage, and aiding the resistance

The Library has been given trial access to the British Online Archives (BOA) collection Secrecy, sabotage, and aiding the resistance: how Anglo-American co-operation shaped World War Two. Giving you unique insight into US-UK diplomacy, intelligence sharing, and sabotage operations in enemy territory from 1939-1954.

You can access this online resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 9th May 2018. Read More

On trial: Migration to New Worlds II: The Modern Era

The Library currently has trial access to Migration to New Worlds II: The Modern Era from Adam Matthew Digital. The Modern Era presents thousands of sources focusing on the growth of colonisation companies during the nineteenth century, the activities of American immigration and welfare societies, and the plight of refugees and displaced persons throughout the twentieth century.

You can access this online resource via the E-resources trials page.

Access is available both on and off-campus.

Trial access ends 14th May 2018. Read More

Free book alert! Grab the latest edition of our Art Collection

We have some great news to share. The 3rd edition of the University of the Edinburgh Art Collection is hot of the printing press! Once a year since 2015, we’ve produced a booklet that introduces various parts of our Art Collection to staff, students and members of the public. Read More

We have some great news to share. The 3rd edition of the University of the Edinburgh Art Collection is hot of the printing press! Once a year since 2015, we’ve produced a booklet that introduces various parts of our Art Collection to staff, students and members of the public. Read More

LaFollette’s International Encyclopedia of Ethics – now available online!

![]()

The International Encyclopedia of Ethics, edited by Hugh LaFollette, covers major philosophical and religious traditions, with entries wriitten by nearly 700 different highly respected thinkers from around the world.

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....