During my initial survey of the New College Collections, it was immediately evident, although not surprising, that the majority of the archives stemmed from the work of men or their institutions. What it did mean, though, was that those collections which belonged to women stood out all the more.

Leaving aside the archives of the Centre for the Study of World Christianity in which women missionaries play a significant role, there are three collections with a female provenance which immediately spring to mind.

The first of these are the papers of Betty Darling Gibson (1889-1973), who worked on the International Review of Missions with Joe Oldham (ref. GD5: http://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/5/resources/85273). The second would be the papers of Margaret Duncan Campbell (ref. GD 37: (http://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/5/resources/86251) while the third would be the papers of Rachel Kay or Wilson (c.1750-1815) (ref. MS WIL 3).

With this last collection, what struck me was that the author of the manuscripts was only referred to as “Mrs James Wilson, wife of James Wilson, ship’s captain, Leith”. As with Betty Gibson, whose biographical details were hard to find in the shadow of her friend and colleague Joe Oldham, I was keen to give Mrs Wilson her given name and dates for the record. Her contribution to history is a curious set of journals recording her religious experiences, including her attendance at church, interlaced with family history, notable events in her own family life and what she saw as evidence of God’s influence on her own life and the life of her family past and present.

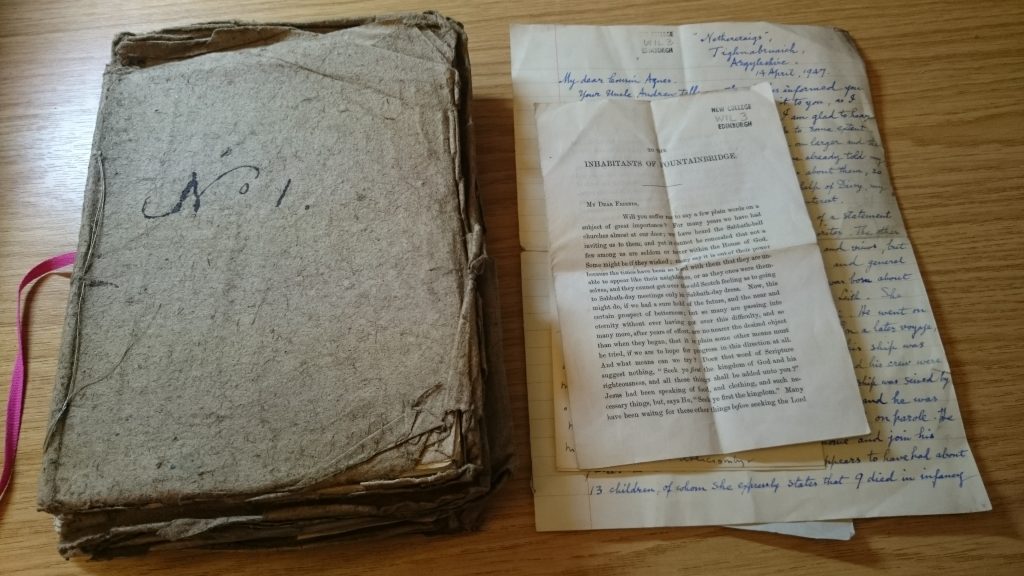

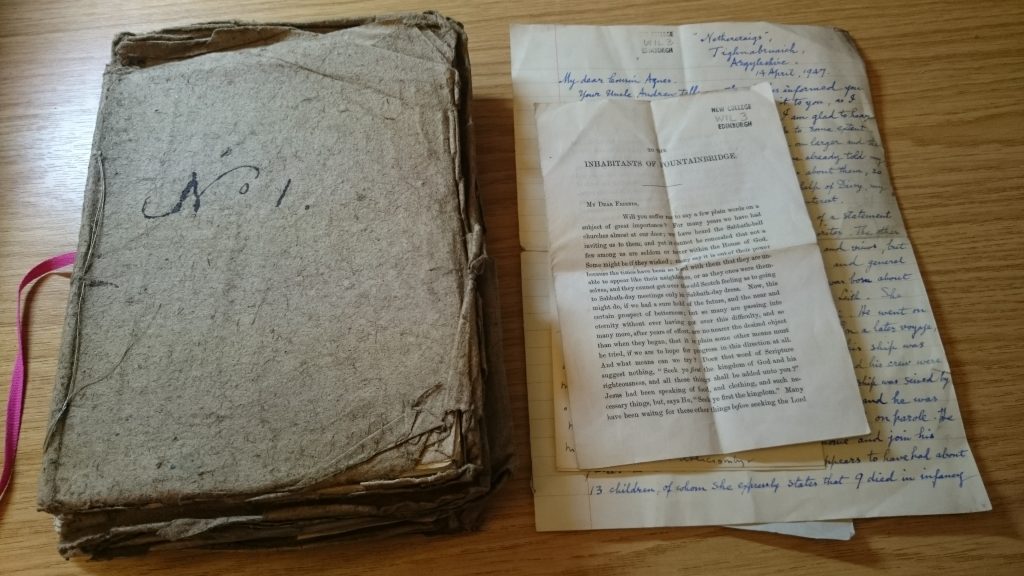

The papers of Mrs James Wilson aka Rachel Kay or Wilson (c.1750-1815) ref. MS WIL 3.

The journals run to six notebooks, each of around 50 pages of manuscript, starting around 1771 and finishing in 1812, three years before she died. There are also a couple of loose sheets, which do not appear to belong to any of the extant notebooks.

Accompanying the documents are two letters giving a bit of background to the manuscripts. The first is from April 1947 from Mr J Ritchie, ‘Nethercraigs’, Tighnabruaich, to his cousin Agnes Moncrieff Leys née Sandys. This letter gives a lot of information such as some of the experiences of James Wilson as a ship-captain: including being captured by Americans during the American War of Independence and then being detained in France for 18 months after which he was ‘persuaded to remain at home and join his father-in-law’s business’.

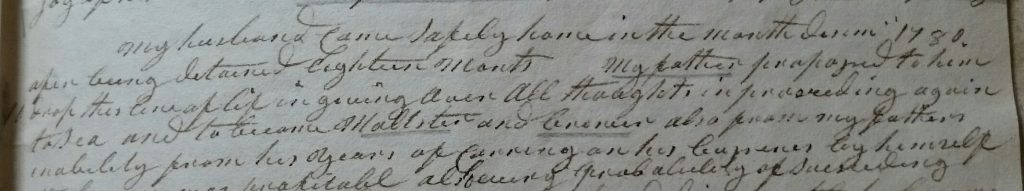

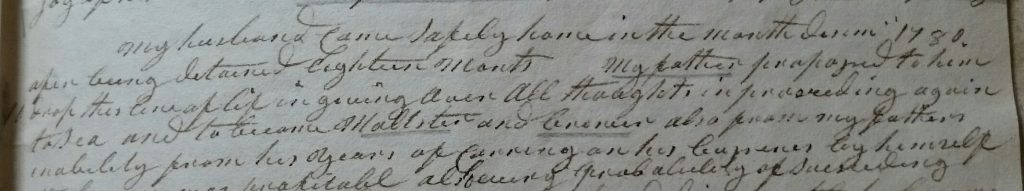

“My husband came safely home in the month June in 1780 when being detained Eighteen month. My father proposed to him to drop this line of life in giving over all thoughts in proceeding again to sea and to become Maltster and brewer also from my fathers inability from his years of carring on his business by himself…” (ref. MS WIL 3 notebook no1, page 43 – image below)

Rachel Wilson’s account of changing her husband’s occupation.

The letter also states that Rachel had about 13 children, ‘of whom she expressly states 9 died in infancy or early youth. This sad mortality was due not to any constitutional weakness, but to small-pox, scarlet fever and measles, which could not then be treated as they can now.’ Ritchie goes on to say that the Wilsons belonged to the Antiburgher section of the Secession Church and were fond of listening to the preacher Rev Adam Gib (1714-1788), and that of the surviving children, David Wilson (1782-), later became minister of the United Secession church in Kilmarnock. Making the personal connection, Ritchie states, ‘I remember being very hospitably entertained by his widow when I was a small boy.’

The manuscripts were eventually passed to New College Library in 1952 by a Miss G Woodward, librarian, who received them from Mrs Hilda Brochet Abercromby, sister of Agnes Leys who by then had passed away. It is clear from annotations made in the manuscripts that family members had read them with a good deal of interest.

At the end of the first notebook, Rachel writes

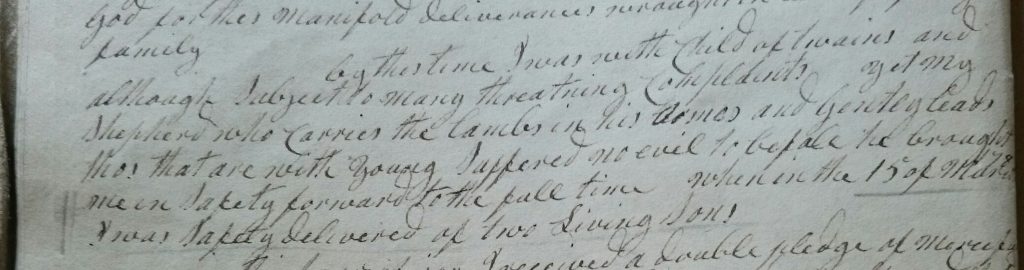

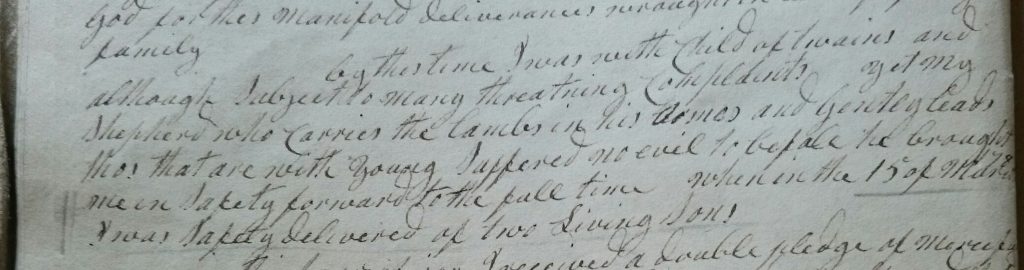

“By this time I was with Child of twains and although subject to many threatning complaints yet my Shepherd who carries the lambs in his armes and Gently leads thos that are with young suffered no evil to befall he brought me in safety forward to the full time when in the 15 of March 1783 I was safely delivered of two living sons.” [William Wilson and John Frazer Wilson] (ref. MS WIL 3 notebook no 1, page 48 – see image below)

Rachel Wilson’s account of having twins.

Perhaps Mrs Wilson’s manuscripts are not the most valuable or beautiful of those which we hold but they do give a clear and striking voice to a woman of both the 18th and 19th centuries.

Kirsty M Stewart

New College Collections Curator

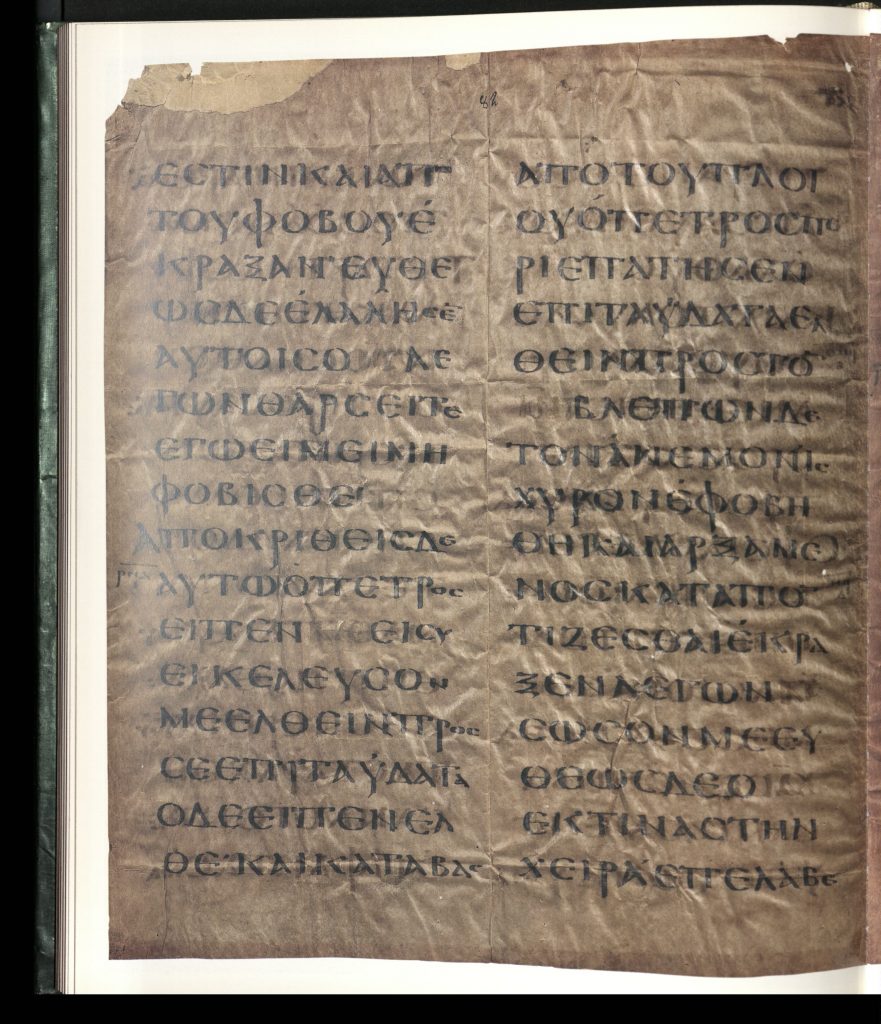

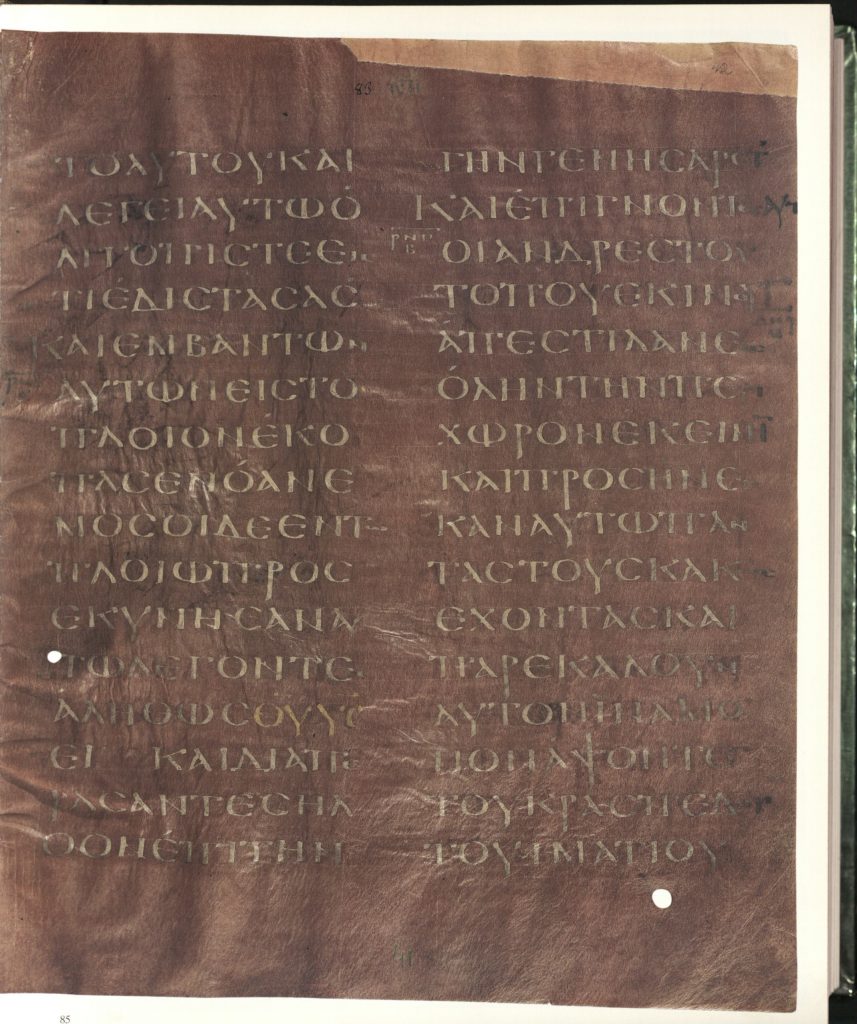

These four letters are abbreviations for the words “God” and “Son” in the text: αληθως θ(εο)υ υ(ιο)ς ει (“Truly, you are the Son of God”).

These four letters are abbreviations for the words “God” and “Son” in the text: αληθως θ(εο)υ υ(ιο)ς ει (“Truly, you are the Son of God”).