An offprint is a separate printing of a work that originally appeared as part of a larger publication, such as an academic journal, magazine, or edited book. Offprints are used by authors to promote their work and ensure a wider dissemination and longer life than might have been achieved through the original publication alone. They are valued by collectors as akin to the first separate edition of a work and, as they are often given away, and may bear an inscription from the author. Historically, the exchange of offprints has been a method of correspondence between scholars; by studying Lyell’s offprints, we will be able to extend our understanding of his network, for example, contrasting the correspondence files, or by following up references in his notebooks, but, to do that, first we need a list! Please welcome Harriet Mack and Claire Bottoms, who are now charged with that task….

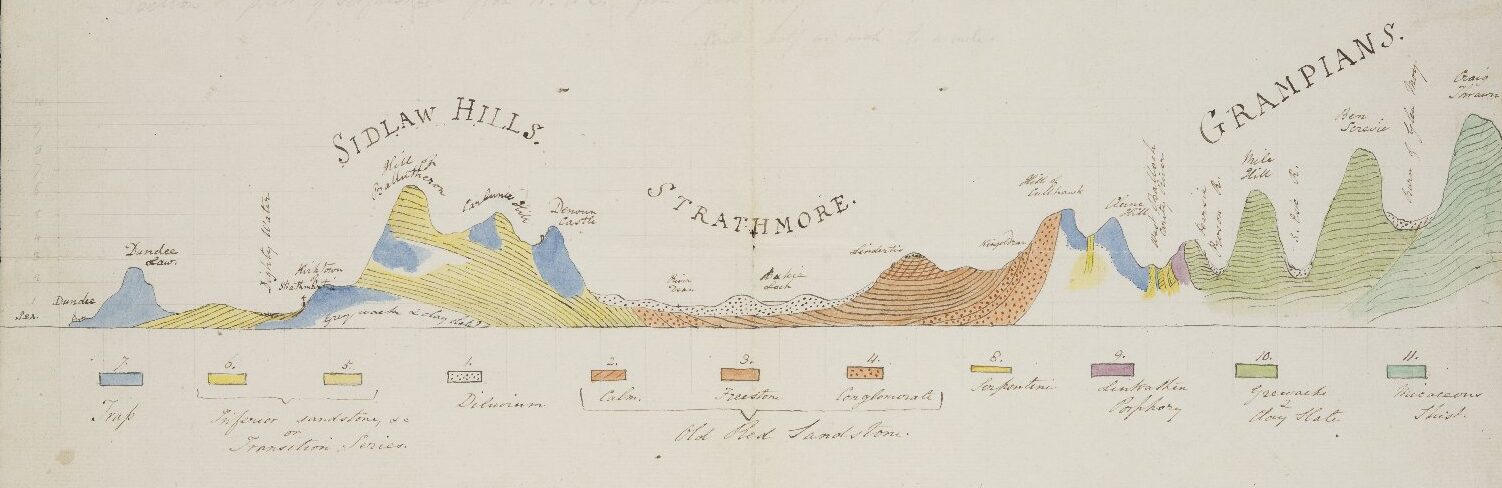

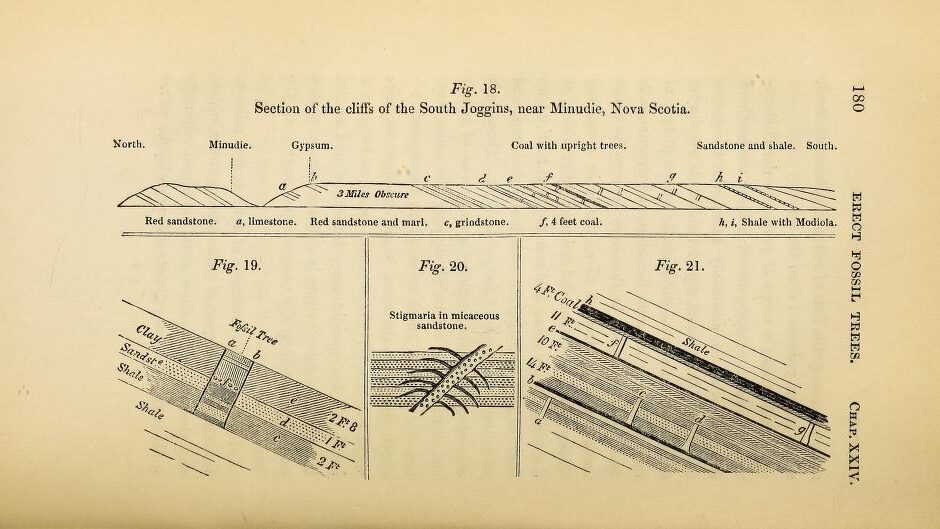

Hi, we are Harriet and Claire, and we have been working for about a month on Charles Lyell’s collection of offprints held by Heritage Collections. These offprints are a series of publications collected and kept by Charles Lyell (1797-1875) assisting with his understanding of scientific principles. Their numerous locations and authors help expose the extensive network of researchers publishing – from Paris, Geneva, Berlin, Sicily to North America – as well as being a record of Lyell’s wide-reaching interests – from geology, history, science, anatomy and civil engineering – to name a few! Using Lyell’s own work and his archive collection, and by listing these offprints, we are recreating Lyell’s network and reference library, providing researchers with a route to Lyell’s own reading and research.

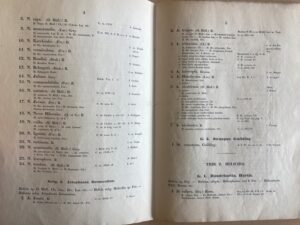

Catalogue of Land Shells in the Royal Collection of the late King of Denmark. Fam. Cochleadea. Trib.1. Vitrinida, by Henrik Hendriksen Beck.

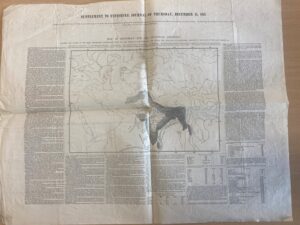

Map of Hindostan and the Countries Adjoining, showing the tracks of the most remarkable earthquakes since 1819, the principal volcanoes and hot wells, the localities of hailstorms, direction of the wind in the rainy season, etc. by George Buist

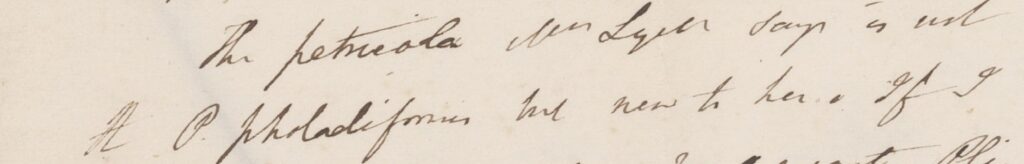

From the get-go we were focusing on the specific primary metadata that could be taken from each offprint. These include the title, author, paginations, language, date, publisher, and any handwritten notes. Titles are often long and specific to geological terminology with many in German, Italian, French, and English with some outliers of Latin and Swedish – we’ve been spending a lot of time on Google translate! What is interesting is that the dates follow a huge range across Lyell’s lifetime, with some early works from 1811 and later works dated in the months before his death in 1875. We are pulling out publishers and journal titles as they provide crucial information concerning the works of learned societies, publications of similar dates, similar interests at the time, and an understanding of the priorities in each year. So far, we have recorded over 200 offprints covering a wide range of topics.

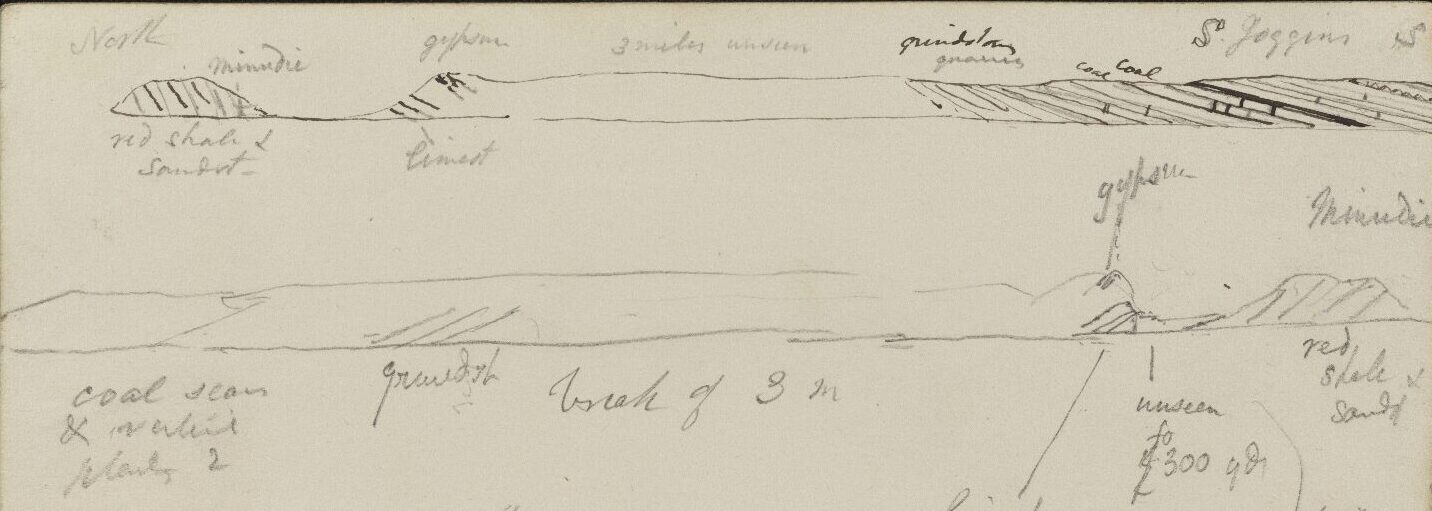

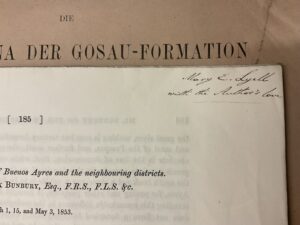

Of great interest are the handwritten notes that accompany the printed works – which reveal hidden details. These appear often on the cover of the offprints and contain dedications by the authors, as well as notes made by Lyell and his team – wife Mary Lyell (1808–1873) and secretary Arabella Buckley (1840 – 1929). Working through the collection, we have uncovered these additional layers to Lyell’s administrative organisation; these added names and dates ensure that the offprint can be identified by the cover as well as the title page.

One of our favourite dedications so far is on the cover of Notes on the Vegetation of Buenos Ayres and the neighbouring districts by Sir Charles James Fox Bunbury (1809-1886) dated 1854. The dedication stands out as it is to Mary Lyell rather than Charles: ‘to Mary E. Lyell with the Author’s love’. Charles Bunbury married Mary’s sister, Frances (1814–1894). Lyell’s wider archival collection holds correspondence that details their family and working relationship – it’s gratifying to see this extend to the sharing of offprints.

Surprisingly colourful, Lyell’s offprints come in a range of pastel shades

Lyell’s offprints have been fascinating to look through. We have gained a colourful wealth of knowledge on specific regions and geological phenomena, as well as an understanding of broader nineteenth century scientific knowledge. At the same time, it is easy to get lost; a common rabbit hole has been the pink journal Revue des Sciences. For this title, Lyell kept specific monthly editions in full. By doing this, he has enabled us to see what else was printed in each edition, widening our understanding of what he and his contemporaries (his network of ‘able investigators’) were reading in connection with one another.

We are really looking forward to continuing looking, and finding more!

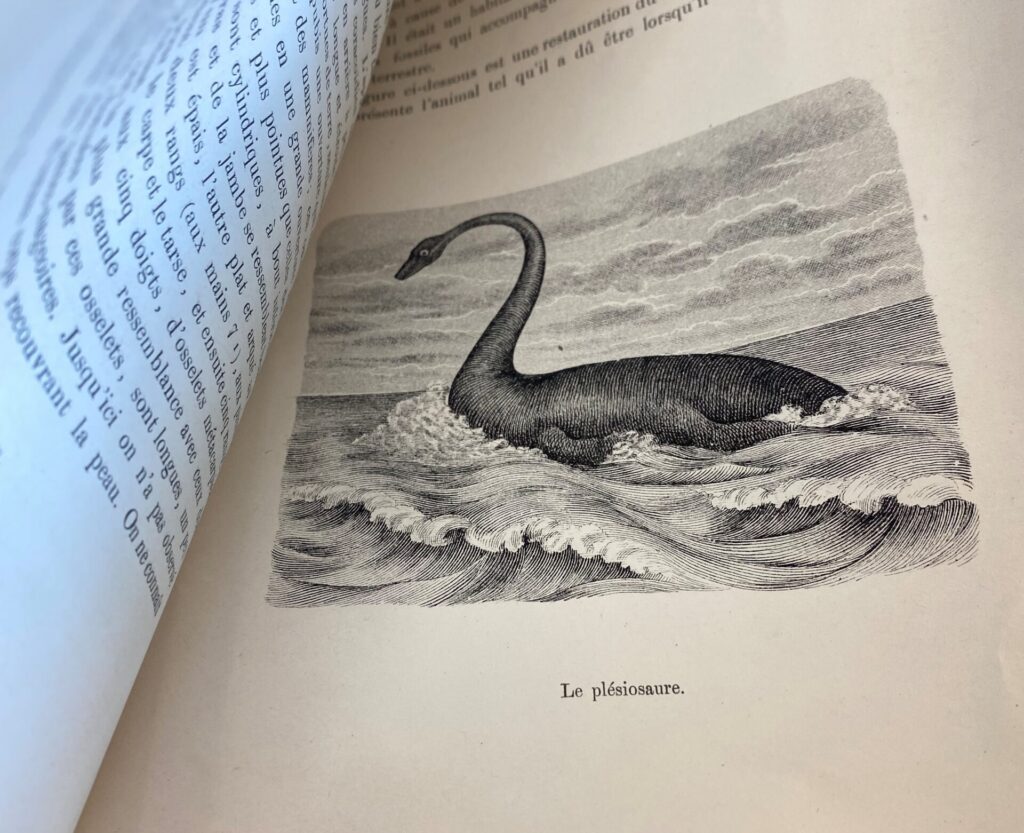

Le Plesiosaurus Dolichodeirus conyb. Du Musee Teyler, By T.C. Winkler