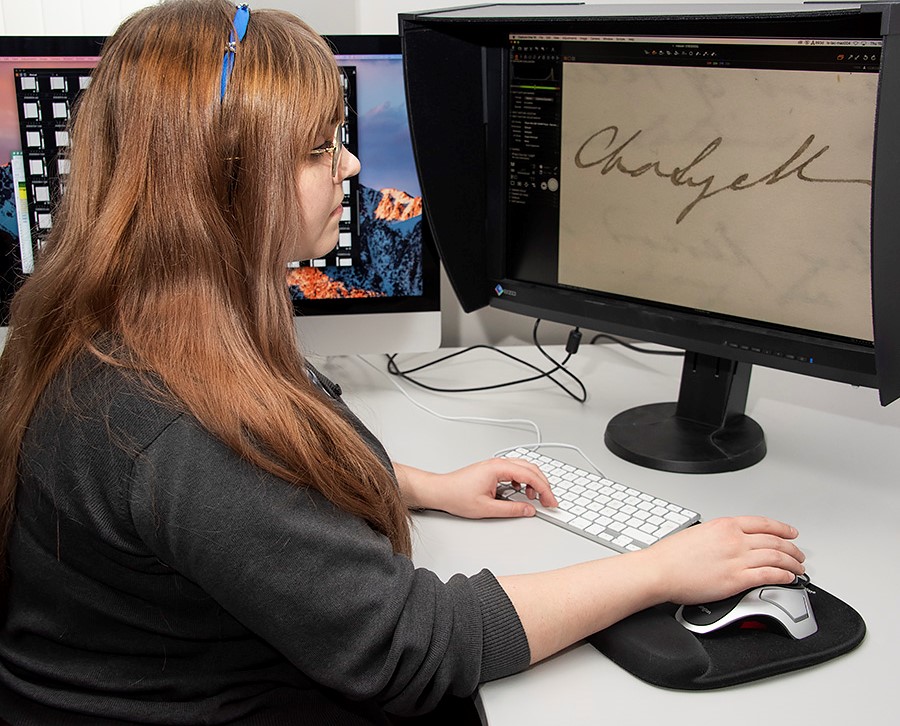

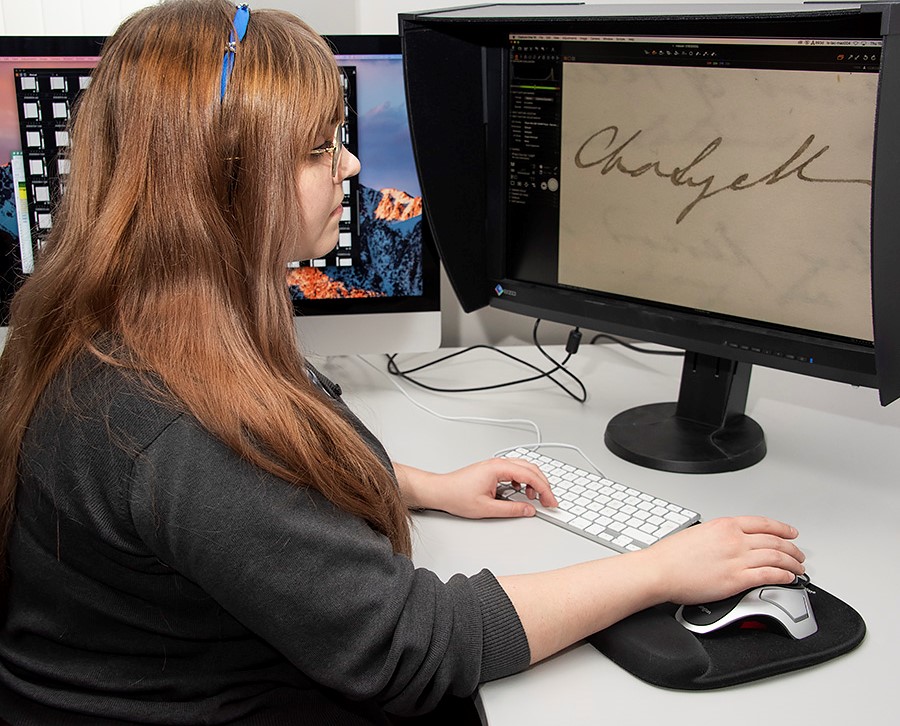

Juliette Lichman working on Lyell digitisation assessment

In November 2019 the Library excitedly welcomed Sir Charles Lyell’s two hundred and ninety-four notebooks into its Special Collections. With support and funding from leading institutions, groups and donations pledged from over 1000 individuals, this tectonic acquisition meant the notebooks were able to stay in the UK and join the Library’s existing collection of Lyell-related materials. As part of the DIU team, I was lucky enough to photograph Lyell’s notebooks, working with the world’s finest quality cameras to digitise a previously private collection into the public sphere and beyond.

Before I dig a little deeper I would like to share a quote from Charles Withers, who we filmed late last year talking about Lyell. He captures the essence of these notebooks perfectly in his description;

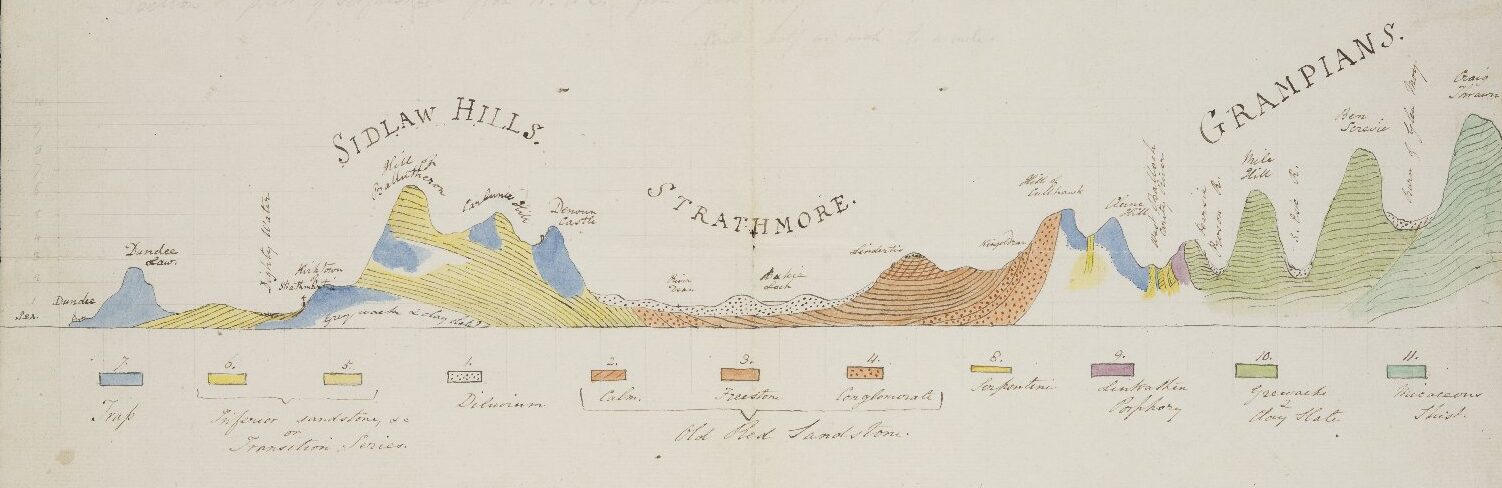

“They contain, in a sense, the emergence of thought of one of the world’s leading Earth scientists. But Lyell is much more than that. Lyell was a leading geologist but he was also a geographer, an antiquarian, an archaeologist. He writes with literary references, he writes with a lawyer-like precision, and he’s in touch with very many people whose names, along with Lyell’s, inform our understanding of the emergence of 19th century science.”

Professor Charles W J Withers, Ogilvie Chair of Geography,

University of Edinburgh, Geographer Royal for Scotland

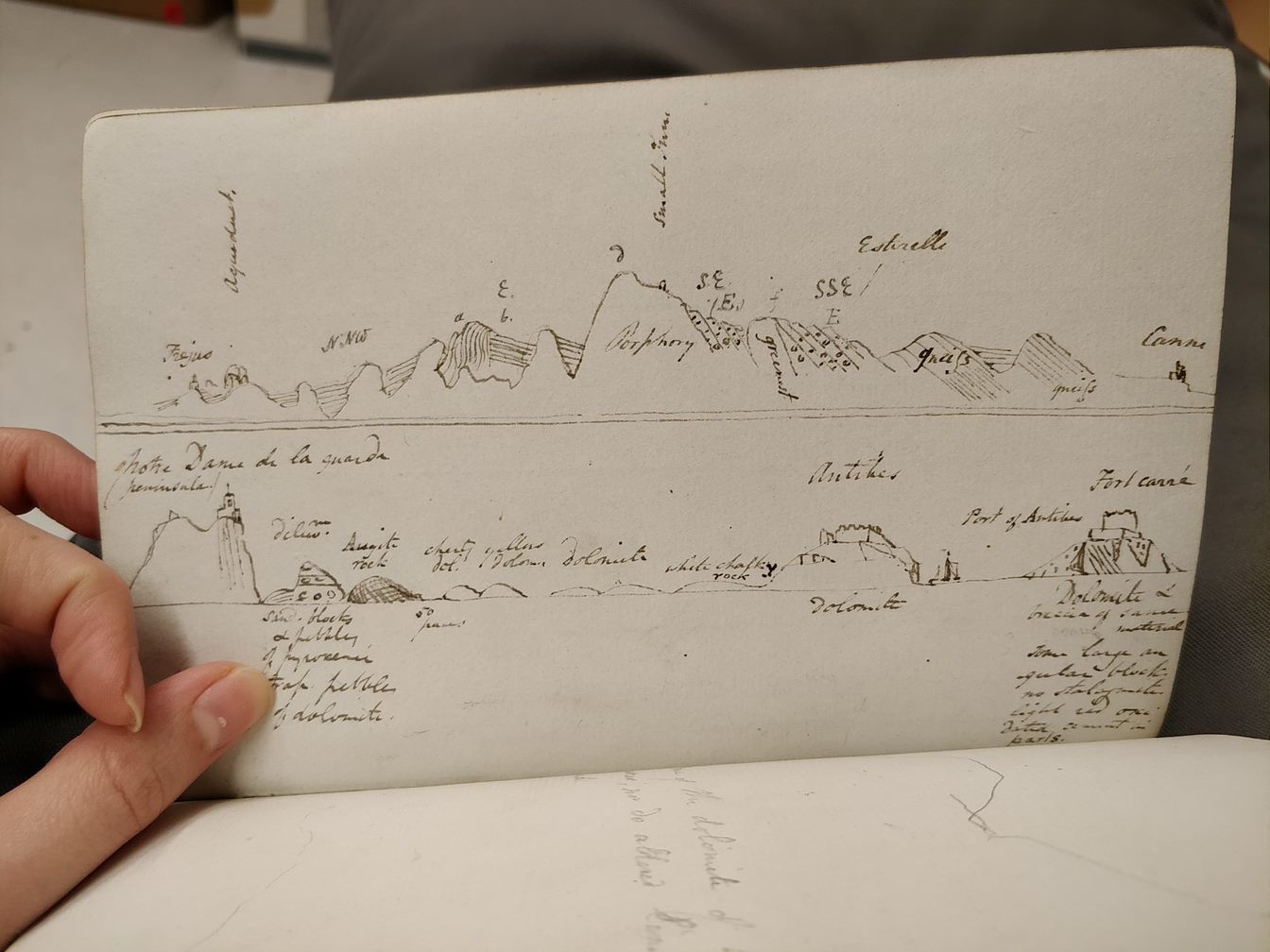

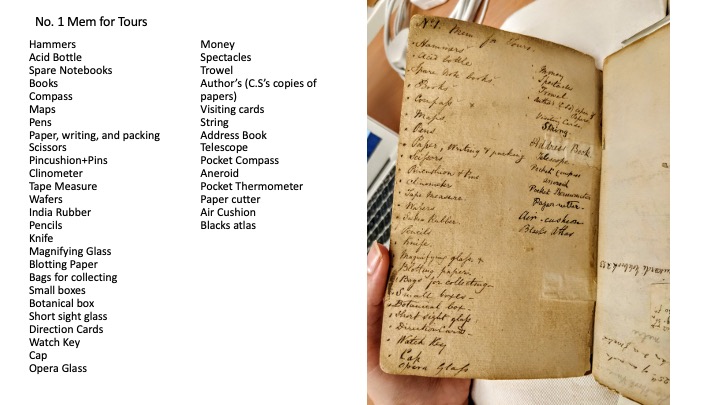

We’re very lucky that Lyell was such a great organiser and essentially catalogued his notebooks for us. With a robust system of pagination and a glossary, he was able to quickly reference information when needed. These small, unassuming notebooks accompanied him everywhere, and in his regular ‘Memoranda for Town’ (a.k.a. to-do lists) there are mentions of particular notebooks which he wanted to pack for later reference, as seen in no.4 below. Very conveniently the locations he visited are neatly labelled on the front of the notebooks. The writing within, however, can be difficult to decipher in some cases, especially where Lyell used his own form of shorthand and references, or if he was in the field resisting against the elements and pressure of the wind.

I find that to-do lists are a simple and yet revealing insight into our every day lives and passing thoughts; little reminders which help us to achieve a larger goal or shape our daily lives. Without having to read a whole passage as you would in a journal, we are able to get a sense of Lyell’s day to day life.

My favourite list is for items to take on an upcoming voyage. There is a glimpse of ‘Lyell the husband’, as he mentions a hat box and a bonnet box, separately, and again, a parasol and an umbrella, alluding to his wife’s presence with him. Indeed, this notebook is from 1837 and the catalogue description indicates:

“This notebook was kept by Lyell during his travels with Mrs. Lyell to Denmark and Norway, where they focused on contact zones between sedimentary rocks and large intrusive bodies of granite and syentie, as well as dykes and sills.”

If you wondered what it was like to travel with Lyell, this is a great example of how he packed light.

I came across an example of ‘Lyell the brother’ in this simple note. His sister, Marianne was a keen lepidopterist, and enjoyed collecting and naming insects. This was especially popular in Scotland, where much of the flora and fauna had no official name. He writes, ‘Curtis – No. 1. Did he not find a spider’. Maybe it was of personal interest, but there is no doubt he would have had illuminating conversations with his sister about entomology and the natural world, perhaps describing foreign insects he encountered in the field, to her delight!

Lyell was well acquainted with the notable entomologist, John Curtis which is evident in this letter he sent to his sister in 1827;

“Dear Marianne, Curtis sends me a note to say that there are good things among the Spring insects, and says the Miss Lyells will do wonders in Scotland. He hopes you will get some general knowledge of botany, as a little knowledge even of Scotch plants, would, he says, double the value of your entomological information. “

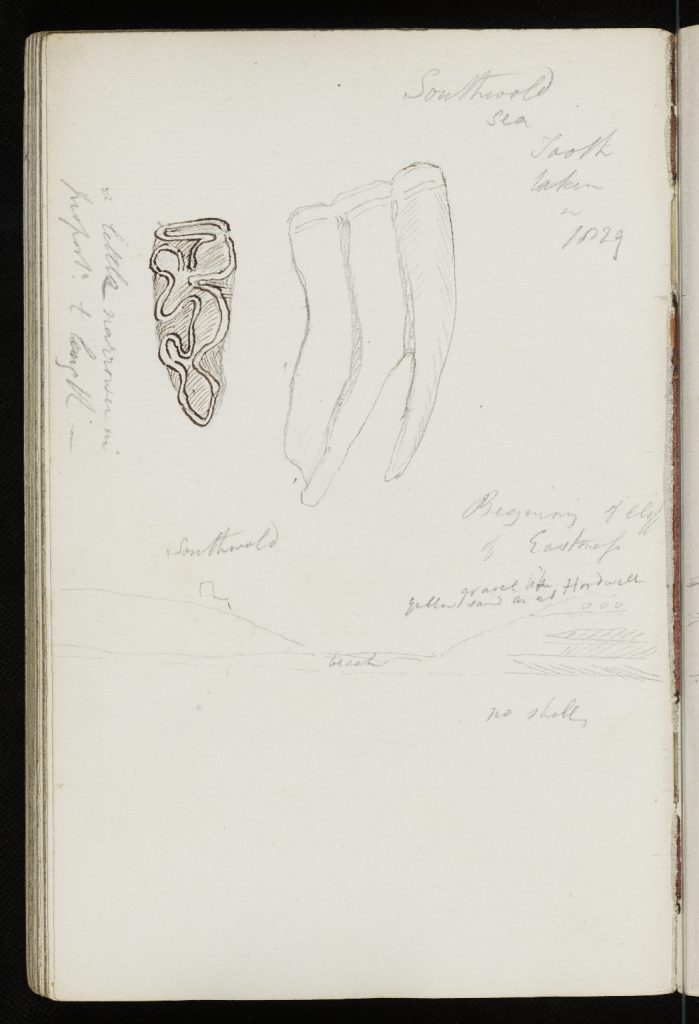

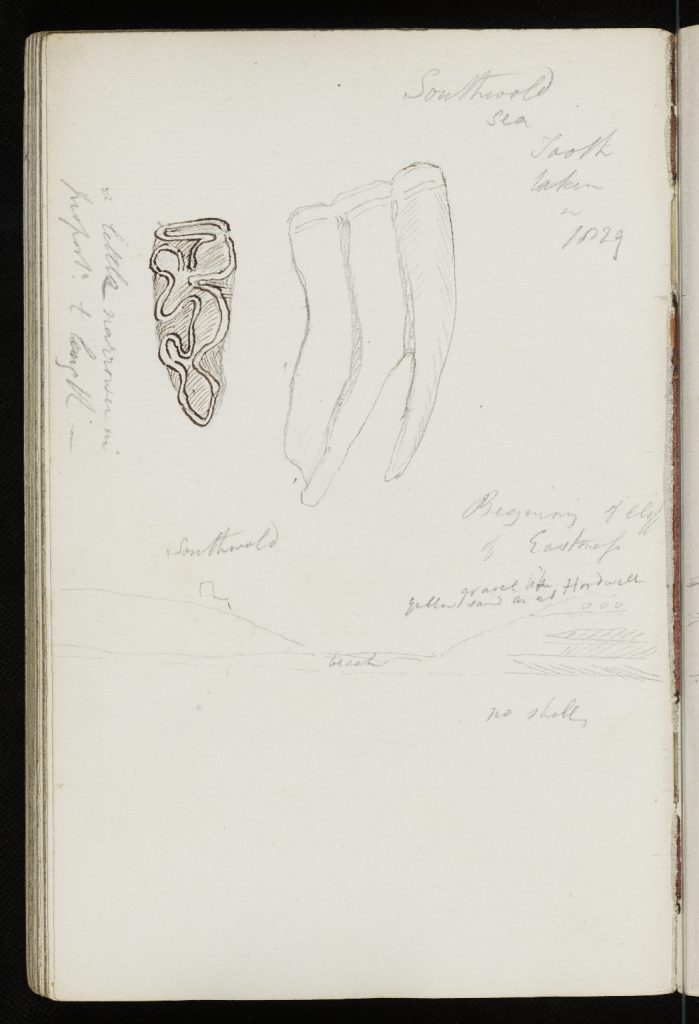

Another favourite find of mine was this illustration of what I assume to be a bovine tooth, with a sketch of Southwold Sea and the beach where he found it. After walking back and forth along the beach, looking intently at the sand for specimens, he stops and notes sadly “no shells”, only teeth!

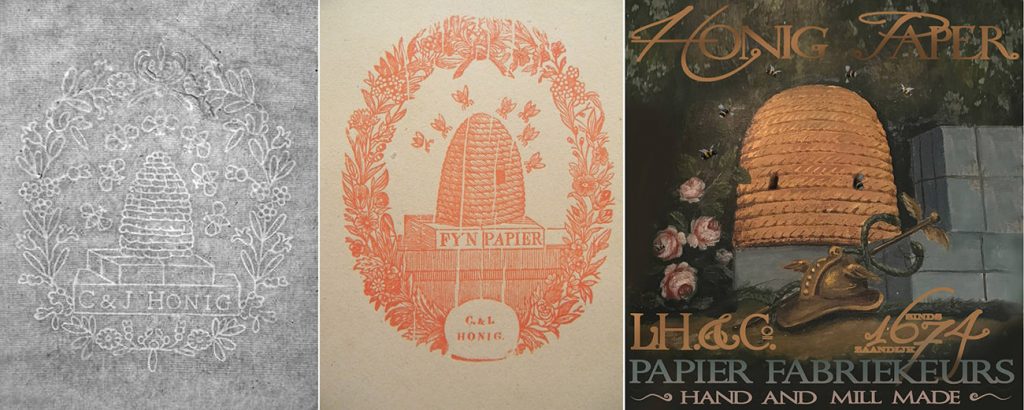

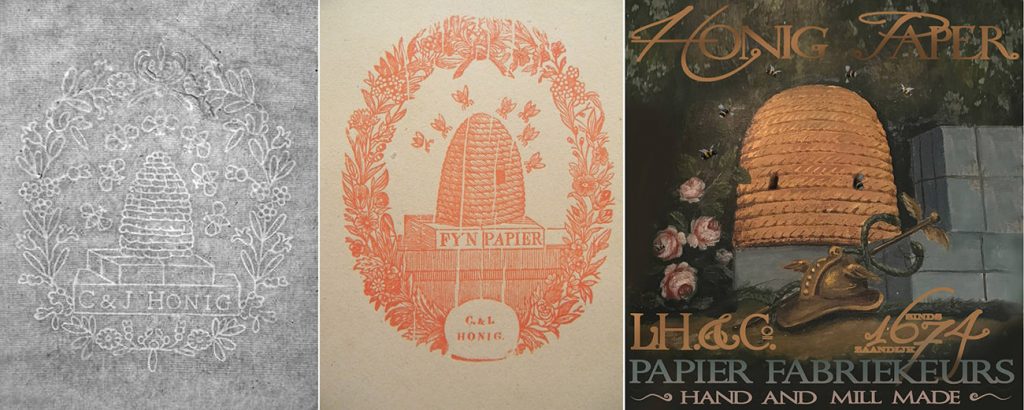

My most recent find in the notebooks was the most exciting by a landslide. We often come across interesting and unique watermarks in our department, but we found one in the notebooks which was very sweet and ornate. This was found in a loosely bound section that Lyell added to the start of a notebook, acting as a preface. The watermarks in the corresponding volume do not bear the same image, so it’s likely that he needed extra paper while travelling and bought some directly from the supplier.

The ‘Beehive’ watermark originated with a family of Dutch papermakers by the name of Honig [honey], who owned mills in Zaandyk (1675–1902). The coat of arms of the Honig family (incorporating the beehive motif) became a watermark extensively copied throughout the Netherlands and abroad in places such as Russia and Scandinavia.1 The ‘Beehive’ watermark became a common motif for Dutch papermakers and those who wished to allude to Dutch papermaking. Eventually it also came to represent a particular paper size.

National Gallery of Australia

https://nga.gov.au/whistler/details/beehive.cfm

Here are a few examples of watermarks and branding from C&J Honig. Note that ours is very similar to the first watermark, with the exception of larger bees.

We’re thrilled that this second batch of notebooks is now digitised and available online for all to enjoy. I photographed Lyell’s notebooks for the majority of the year, and with the added lockdown and social distancing restrictions, for a time it was just myself and the notebooks in the DIU. I will certainly miss seeing Lyell’s familiar scrawling hand and pencilled field sketches – intimate notes that he likely never anticipated sharing with anyone.

It’s been just over a year since our acquisition of these notebooks and it feels as though we have only scratched beneath the surface of the treasures contained within. They are a rare and fascinating glimpse into this famed geologist’s daily life, and like many others I shall be eagerly awaiting the transcriptions and new discoveries from this most beloved rockstar!

Juliette Lichman

Photographer

Useful Links:

We are delighted to announce that we will shortly be receiving a generous donation from the International Association of Sedimentologists to fully fund the design and development of a new website: Charles Lyell’s World Online.

We are delighted to announce that we will shortly be receiving a generous donation from the International Association of Sedimentologists to fully fund the design and development of a new website: Charles Lyell’s World Online.

.

.

We are excited to offer a new opportunity to experience this collection, a Zoom presentation by the Lyell Project staff on 10 December 2020 at 1pm GMT. This event reveals the ongoing work at the University of Edinburgh with the geological collection of Sir Charles Lyell, a rich corpus of material including his notebooks, family papers, and geological specimens.

We are excited to offer a new opportunity to experience this collection, a Zoom presentation by the Lyell Project staff on 10 December 2020 at 1pm GMT. This event reveals the ongoing work at the University of Edinburgh with the geological collection of Sir Charles Lyell, a rich corpus of material including his notebooks, family papers, and geological specimens.