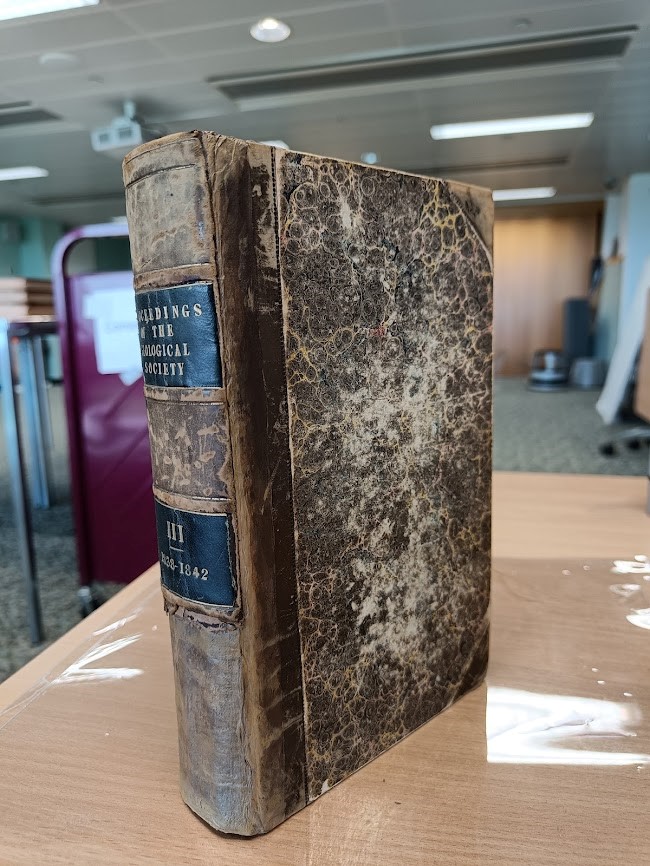

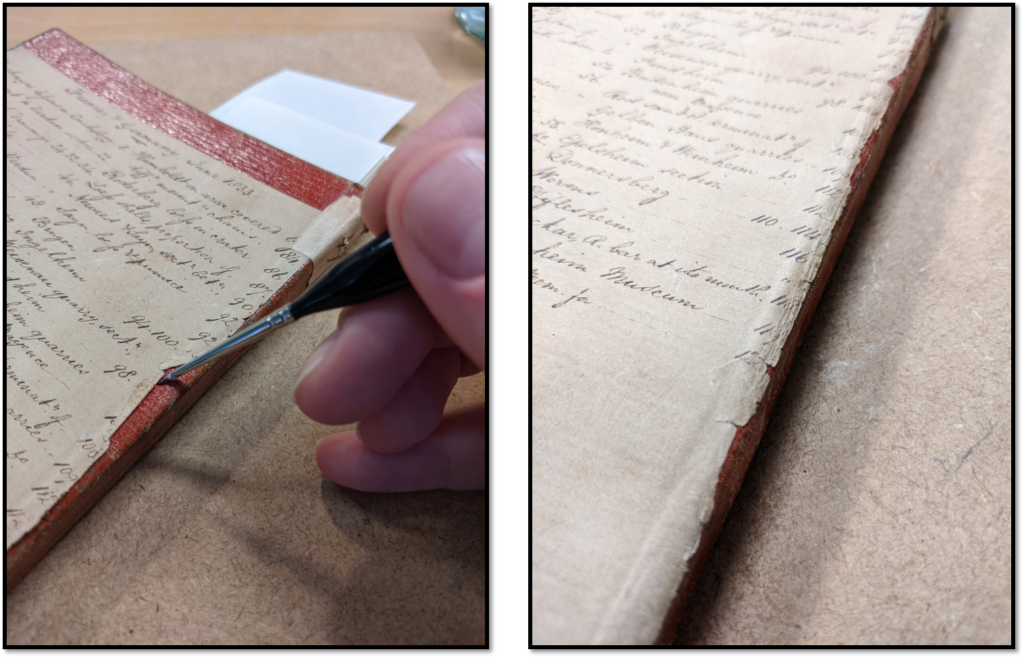

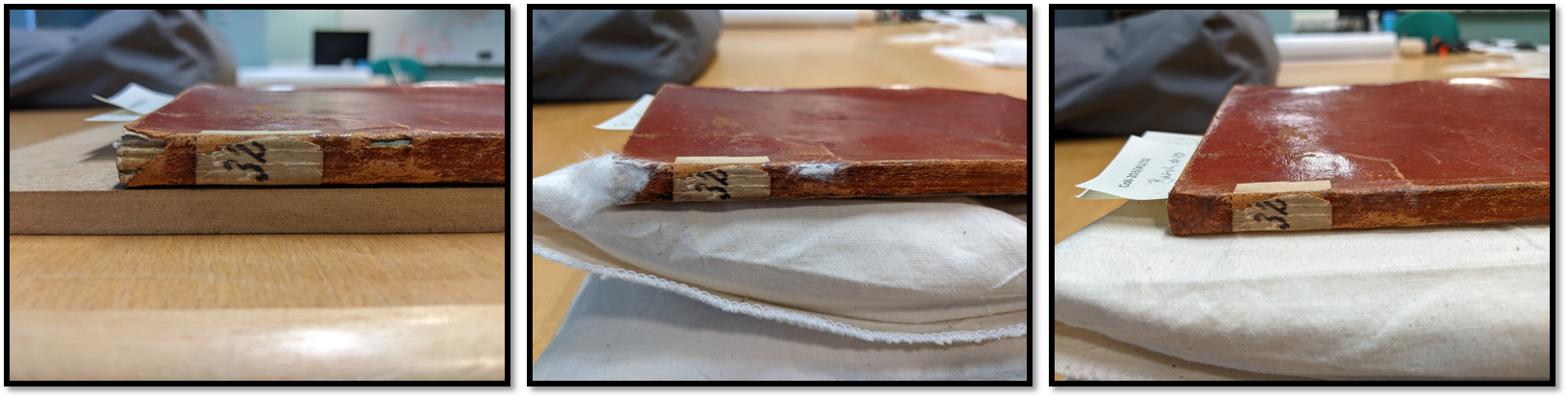

The Cockburn Geological Museum at the Grant Institute holds an extensive collection of over 130,000 geological specimens that reflect the whole spectrum of earth science materials, including minerals, rocks and fossils. Most of these specimens have labels – some have multiple labels, some of these labels are loose paper in the bottom of specimen boxes, while others are glued directly on to the rock or mineral. Some information is written on with red or blue paint. Some specimens have all of the above – some don’t have any labels at all.

There are several specimens at the Cockburn that are clearly marked ‘Sir C Lyell’ – in what looks to be his own handwriting – a good indication that they were originally part of his own collection.

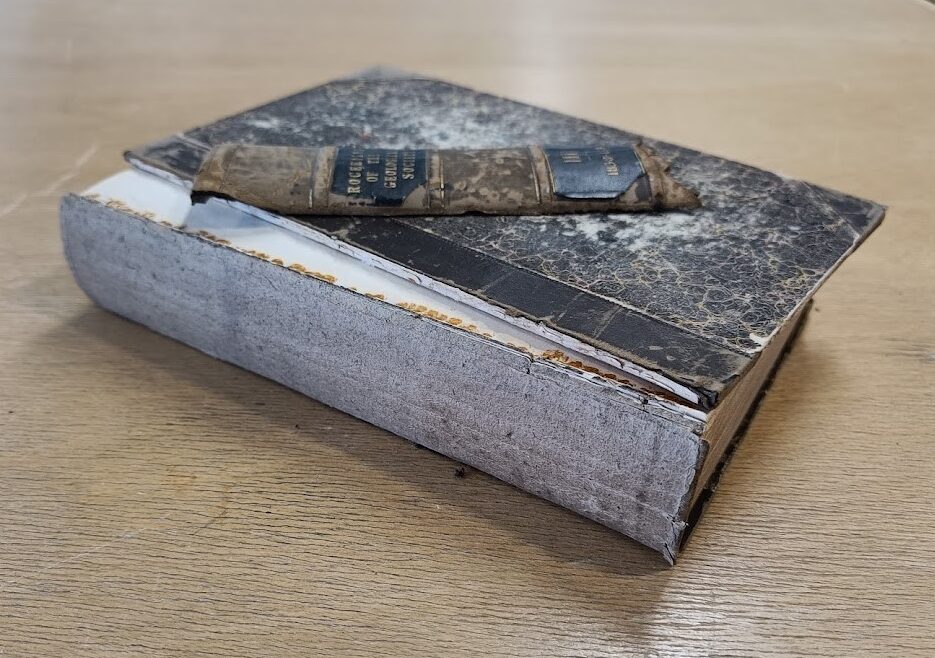

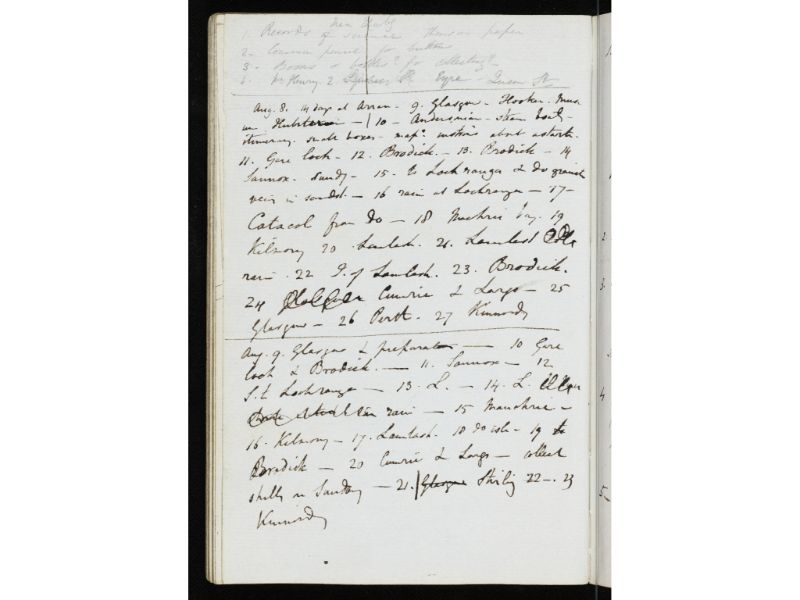

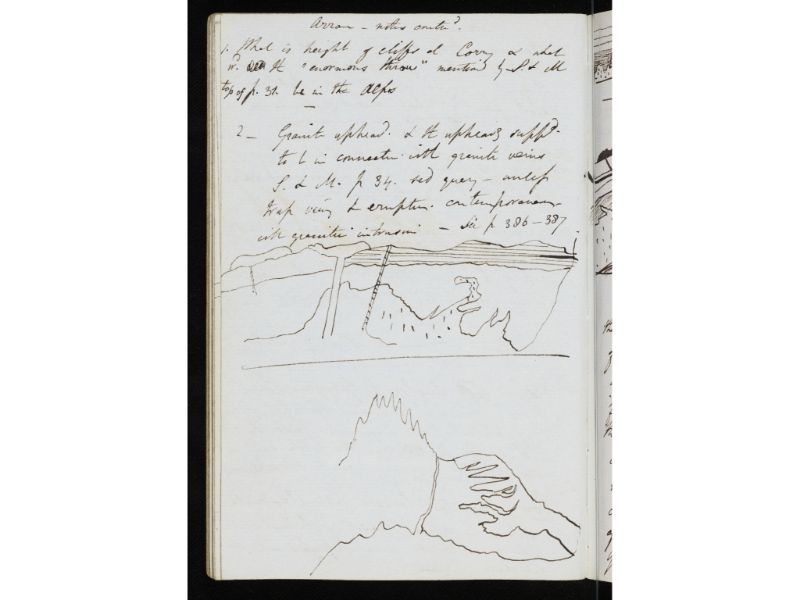

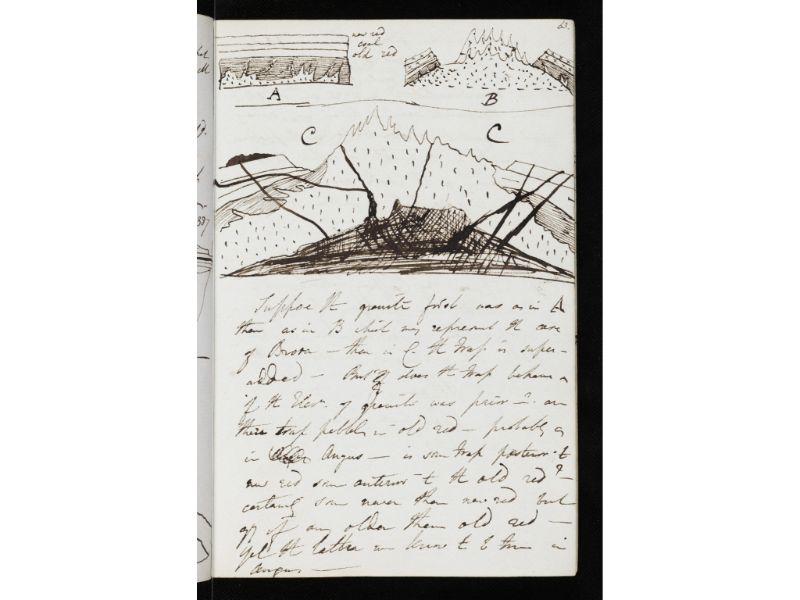

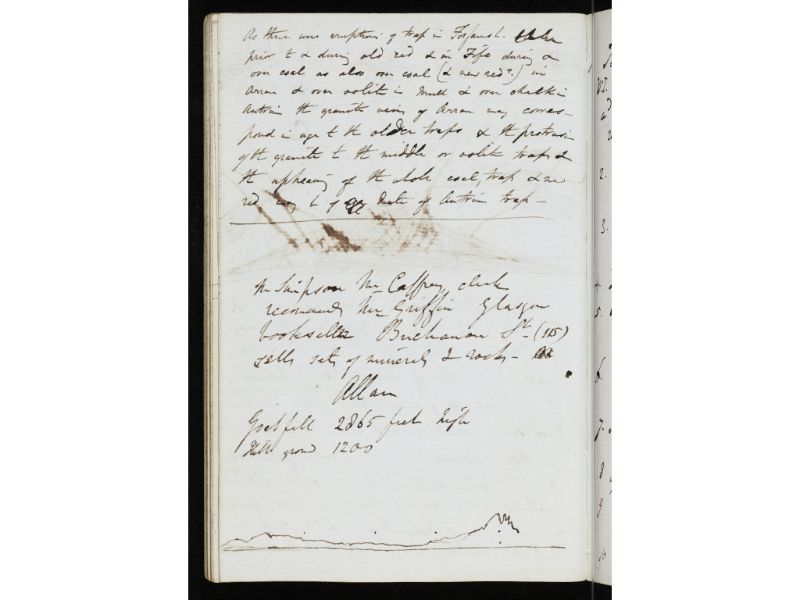

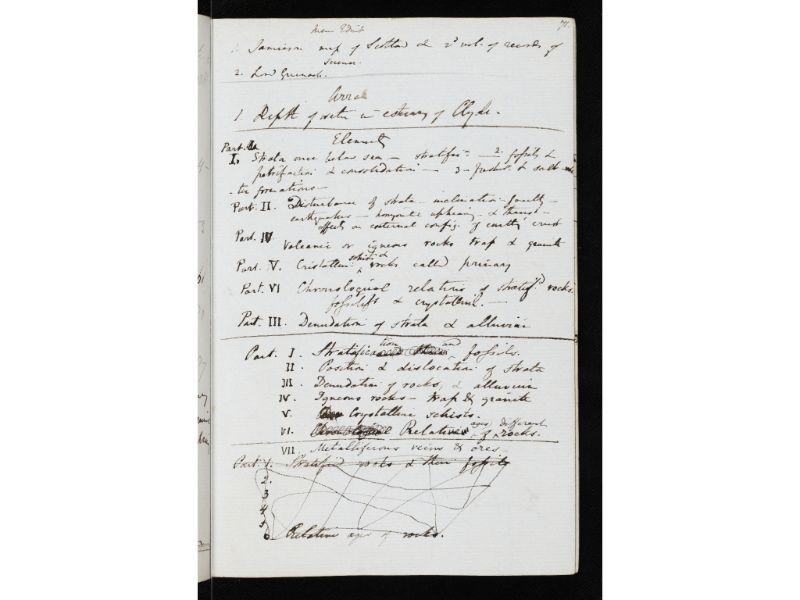

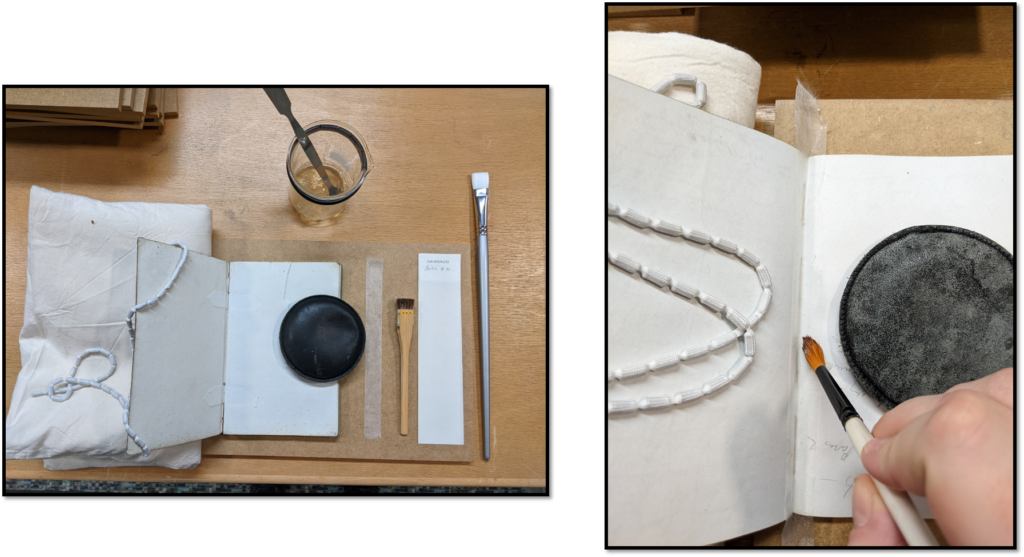

Now that the University of Edinburgh has acquired Lyell’s 294 Notebooks, for the first time, in a long time, both the specimens and the documentary records, can be brought together to share the same space. The notebooks offer the chance to enrich our knowledge of the specimens, adding valuable context and insight into when and where they were collected, and what they were potentially used for.

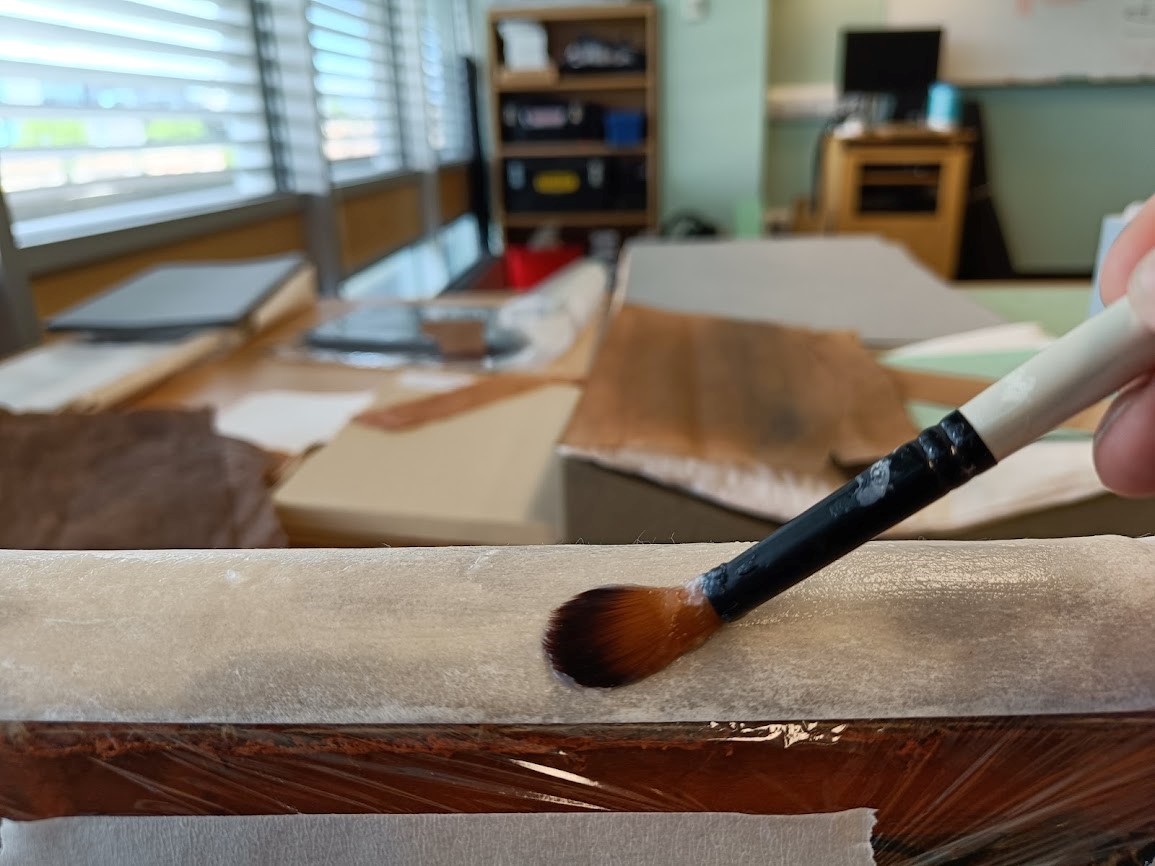

Using our now well-developed Lyell ‘next level’ palaeography skills, we feel ready to explore the links between specimens and the written information – but to get us started, we brought in the label expert!

Postgraduate researcher Kate Bowell is exploring the stories the National Museum of Scotland has told in their collection of 20,000 exhibition labels and how these stories have changed over time (See Kate’s blog here https://blog.nms.ac.uk/2021/12/14/a-history-of-exhibition-labels-and-the-stories-they-tell/ ). Her experience in studying the stories behind labels means she is the perfect person to help us start formulating a plan.

We were also pleased to have undergraduate student Will Adams join us. Currently in 4th year Archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, Will’s interested in archives and how they relate to archaeological collections – he is also on the quest to find a dissertation topic.

Could we join forces to help each other out? What followed was a joyous 3 hour discussion – exploring the history of labels, the history of collections, why people collect, how people use labels, personal collection administration, split and movement of collections, the rise and purpose of museums – and how museums subsequently label items, both for use and for public enjoyment.

Lyell’s administration throughout his collection – his page numbering, indexing and the labelling of his specimens – show that he actively used them as a resource for his work. No actual catalogue exists – and so we have to start slowly working out how he kept his collection in order, and how he used specimens to aid his understanding. Now that the collections are together, it should be possible to start to see how it all linked up – and there is huge potential to learn much more about the specimens.

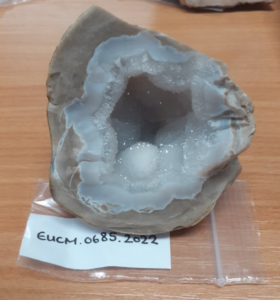

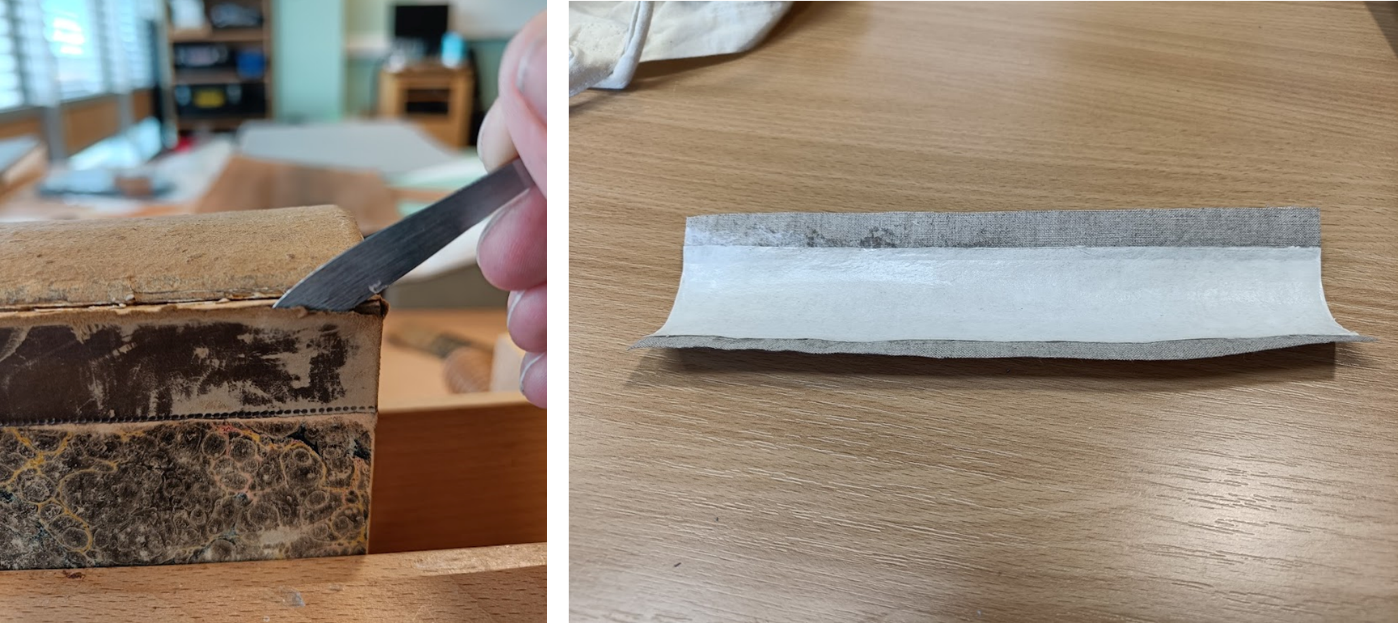

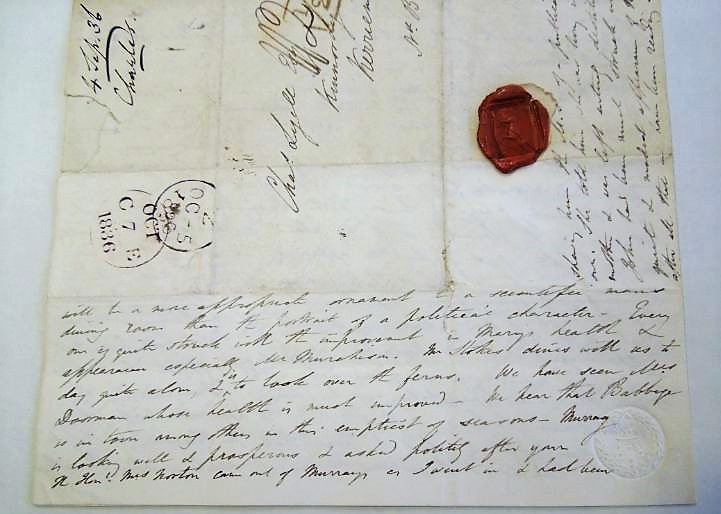

For example, one of the Cockburn’s specimens, and part of Lyell’s original collection is this amazing Agate, labelled in Lyell’s own handwriting:

We recognise Lyell’s distinctive ‘e’ – and the place name Mount Horne points us to British Columbia[1]. The specimen’s original owner is noted by Lyell as the Honourable C.A. Murray. In many ways similar to Lyell, Charles Augustus Murray was an author and diplomat,. He attended Oxford University, and spent several years travelling across Europe and America from 1835 and 1838, describing his experiences in popular books on his return [2].

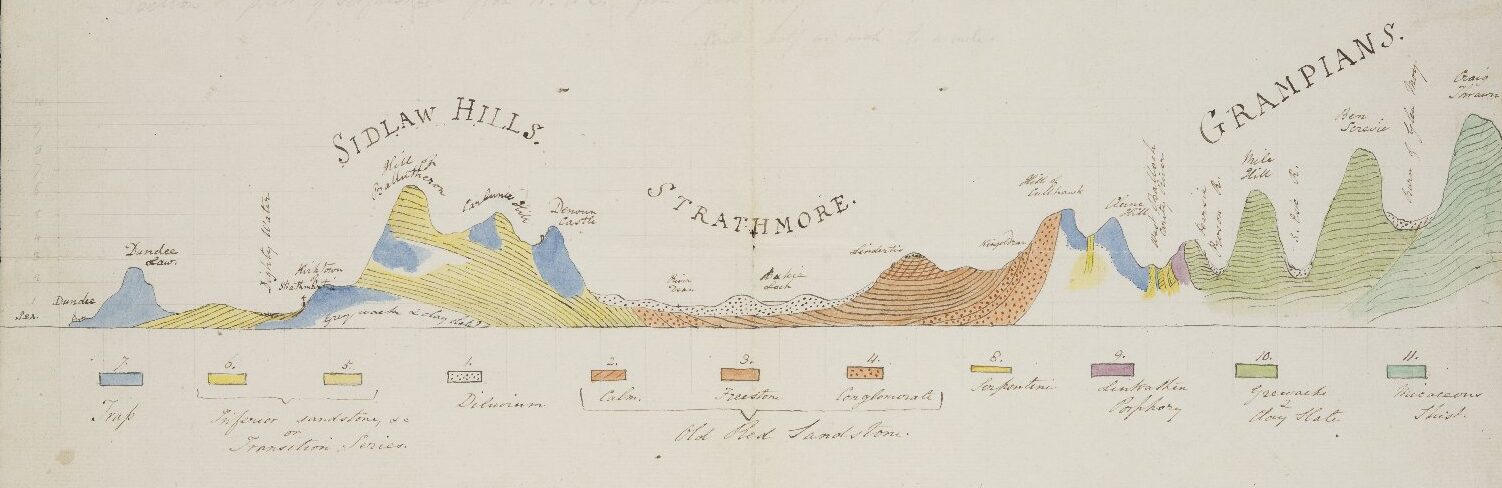

We know Lyell visited British Columbia several times; the collection includes both Charles and Mary’s certificates recording their passing behind Niagara Falls to Termination Rock dated the 7th June 1842; and a card representing Columbia College dated 1853. As we are able to identify critical information – names of people, places, mineral types – on the labels – these can be cross-referenced to text in the notebooks, allowing us to focus in on the history of the specimens. Creating this framework of knowledge allows us to develop our hypothesis about how travel, collaboration, and collecting (or trading) specimens fed into the larger ideas of the time relating to “how the earth systems worked”.

Will’s presence also helped us see how he can add archaeological detail to the specimens. Lyell’s interests where wide ranging, and his exploration of the history of man resulted in him collecting neolithic objects ranging from tools to beads. Of course, we cannot be experts in everything, and with the collection of specimens being held by the Grant Institute, they have been categorised very much as geological specimens. Will’s contribution proved how collaboration with people who can view the objects with an “archaeological eye” adds significant detail to the objects. Our meeting provided him with the perfect opportunity to dive in and begin to think about a project combining his interest in archives and collections. Inspired, Will has booked into the CRC Reading Room to start looking at the collection in more detail, and is talking to his dissertation advisor to firm up a plan.

The benefits in bringing both the collections and experts together are tangible. Collaborative work will really enhance the Lyell collection – indeed, our afternoon spent considering label gave us a practical insight into how he himself worked and used the collection.

Thank you to all the individual donors and bodies who have supported us so far. In addition to our anonymous supporters, we would also like to acknowledge the ongoing support of the Murray family, Jim Hunter, the History of Geology Group and the Geologists’ Association Curry Fund. If you are interested in helping us complete the digitisation project’s funding target that would be wonderful. Individual gifts may be made online at:

Thank you to all the individual donors and bodies who have supported us so far. In addition to our anonymous supporters, we would also like to acknowledge the ongoing support of the Murray family, Jim Hunter, the History of Geology Group and the Geologists’ Association Curry Fund. If you are interested in helping us complete the digitisation project’s funding target that would be wonderful. Individual gifts may be made online at: