Strategic Projects Archivist, Pamela McIntyre started in mid January, and will be leading on the Charles Lyell Project. Pamela introduces herself, and shares her insight on the internationally significant Sir Charles Lyell archive.

Hello! After training in a number of repositories across the UK I qualified as an Archivist from Liverpool University in 1995. My first professional post was a SHEFC-funded project to catalogue, preserve and promote the archives of Heriot-Watt University, and its then associated colleges – Edinburgh College of Art, Moray House and the Scottish College of Textiles. Since then, I’ve worked with local authority, private and business archives, and with fine art and museum collections. I have always really enjoyed the practical elements of archive work, and getting people involved, and consequently, I’ve diversified, working in the third sector with volunteers. My last post was Project Development Officer, Libraries. Museums & Galleries for South Ayrshire Council – some highlights of my time there include breaking the ‘Festival of Museums’ with a ‘Day o’ the Dames’ event (sorry, Museum Galleries Scotland!), hosting an amazing exhibition about the history of tattoos, and spending two days at Troon, Prestwick, Maidens and Girvan beaches in support of COP26. I’m thrilled to join Edinburgh University, getting back to my archival roots – and it’s safe to say, Charles Lyell and I are getting on great!

I’m so impressed with the work that’s been done so far. I want to thank the previous staff for all of their efforts.

I am new to Geology, and one of the ways I get to know collections is by searching for subjects I do know about – using family names or places I know. Lyell travelled extensively, and whilst this may well influence my forthcoming holiday plans – it was particularly reassuring to find and read about his trip to the Isle of Arran – a place I love.

From Hutton’s visit in 1787, many geologists have visited Arran. Robert Jameson published his account in 1798, followed by John Macculloch in 1819. Geologists from overseas also visited, and Lyell had studied von Dechen and Oeynhansen’s accounts of 1829. As Leonard Wilson notes in his book Charles Lyell: the Years to 1841:

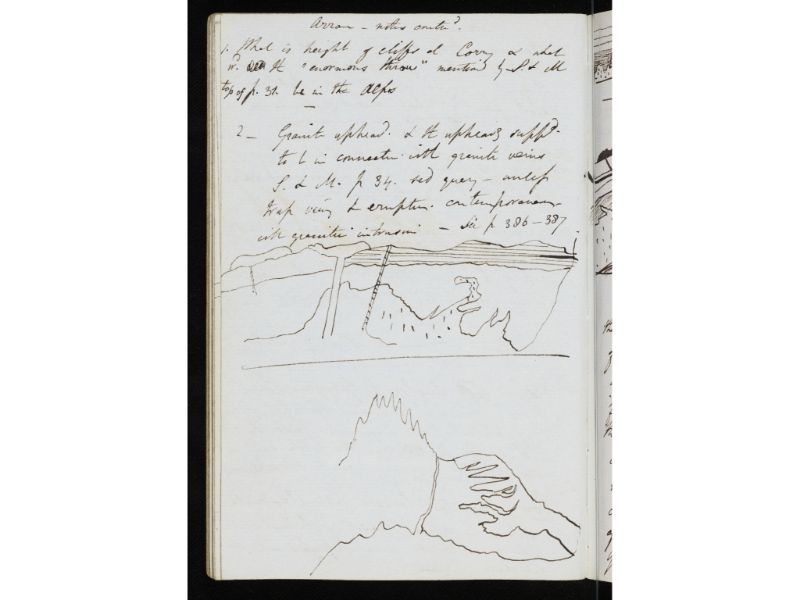

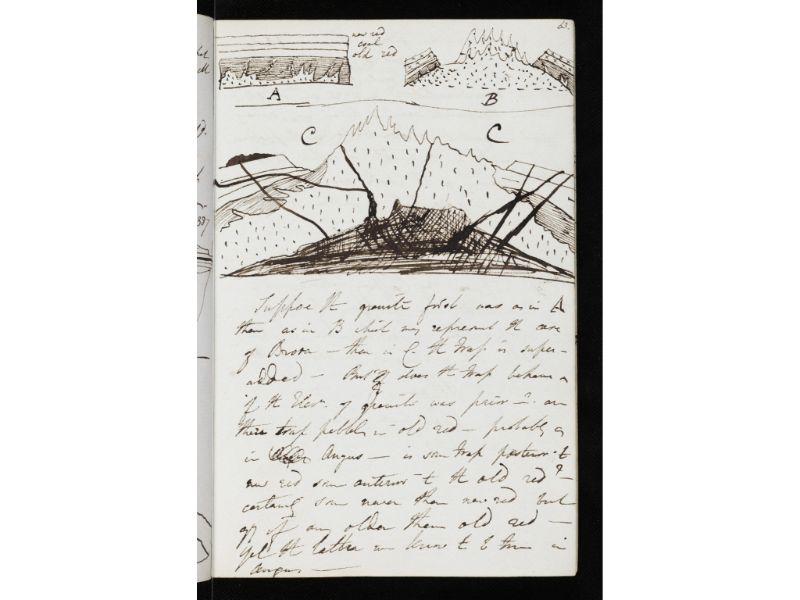

With its granite mountains and numerous dikes of traprock intersecting and altering stratified sedimentary rocks, Arran was a veritable laboratory for Lyell’s study of hypogene rocks and for the confirmation of his metamorphic theory.

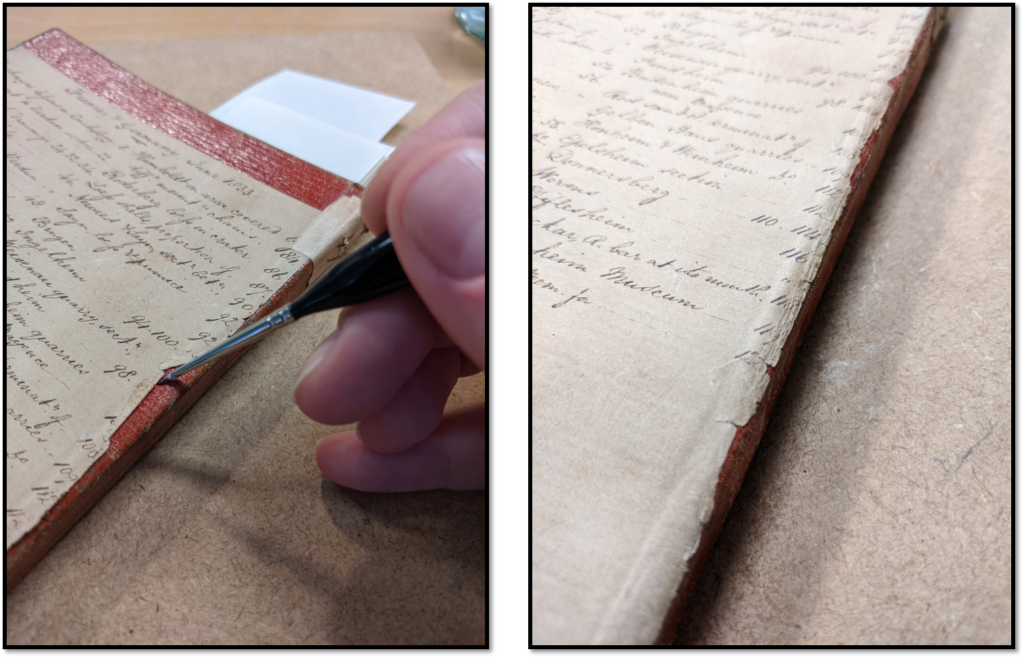

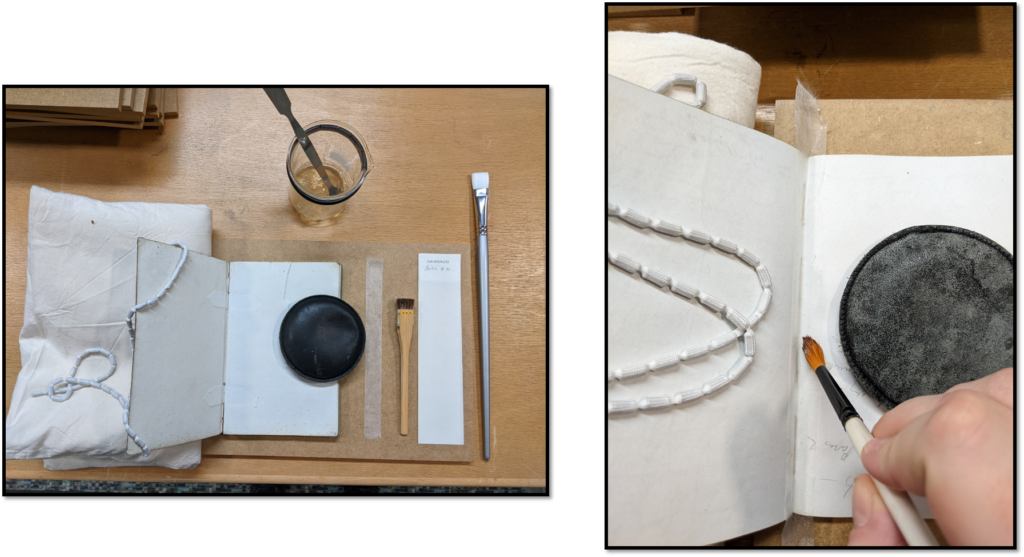

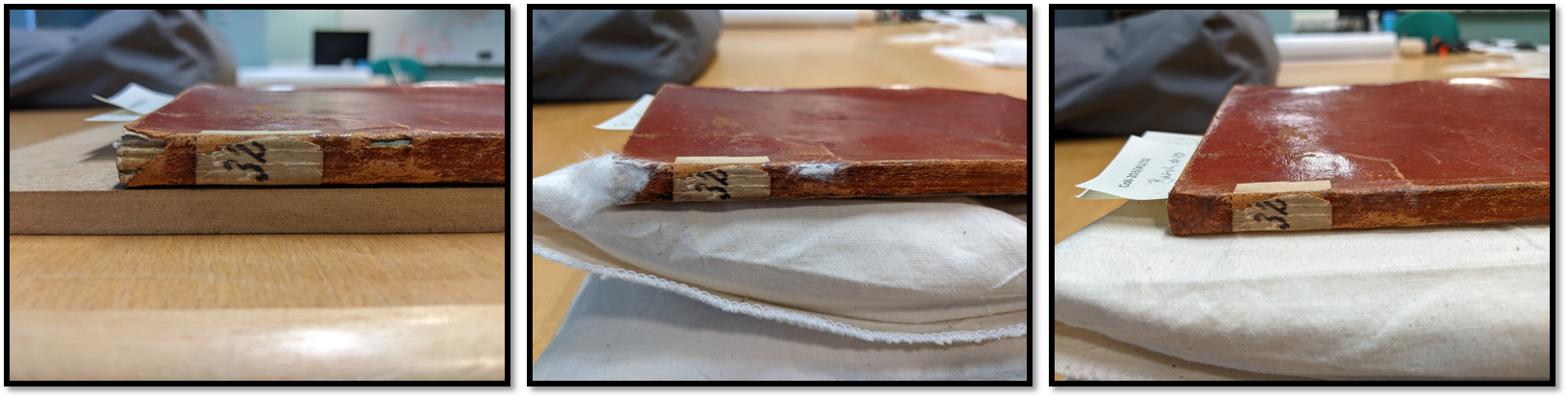

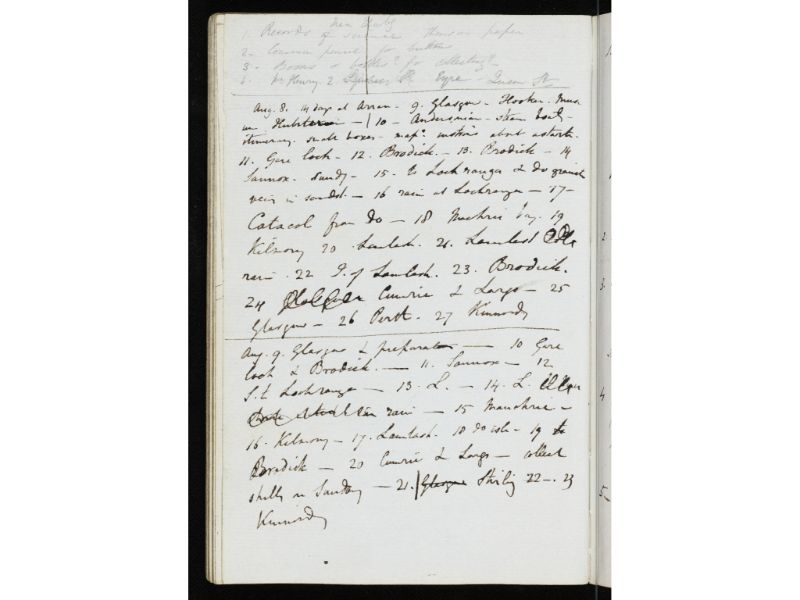

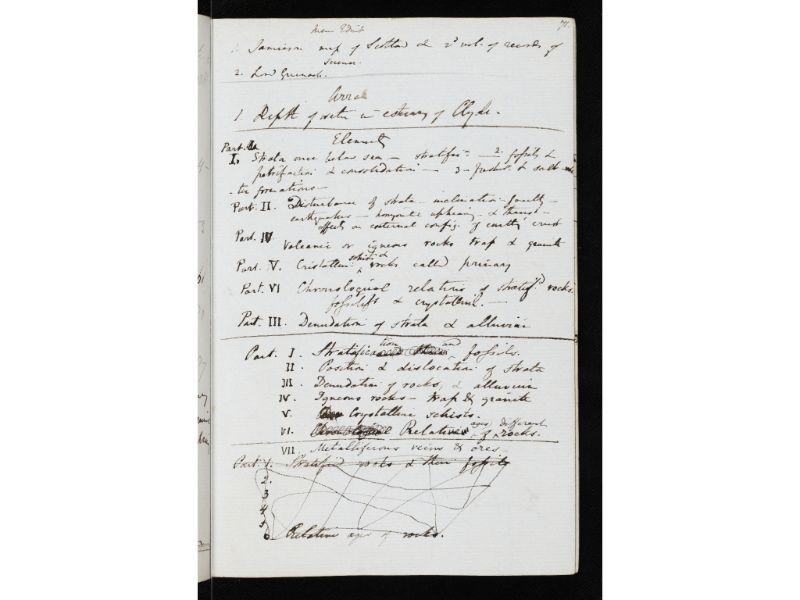

Charles and Mary Lyell stayed at Arran for the first two weeks of August 1836, a trip chronicled by Lyell in Notebooks 62 and 63. Notebook 62 is digitised, and available on the University of Edinburgh’s LUNA image website. From page 60, Lyell noted their plans – arriving in Glasgow, a meeting with Hooker, and stop offs at both the Hunterian and the Andersonian – then plans his trip around the island.

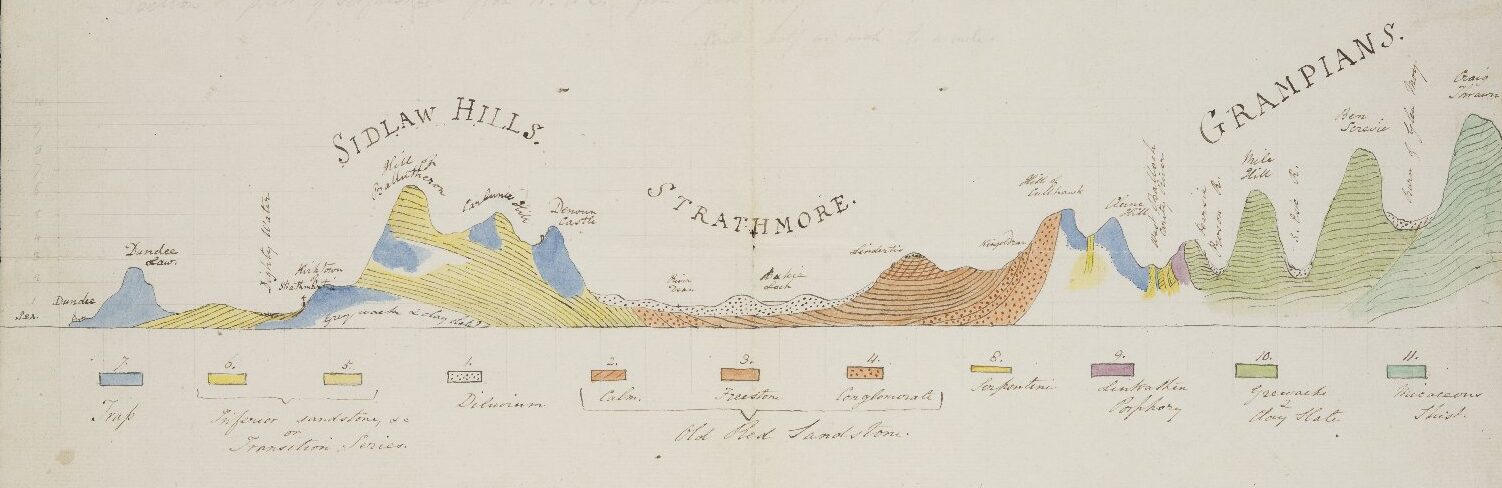

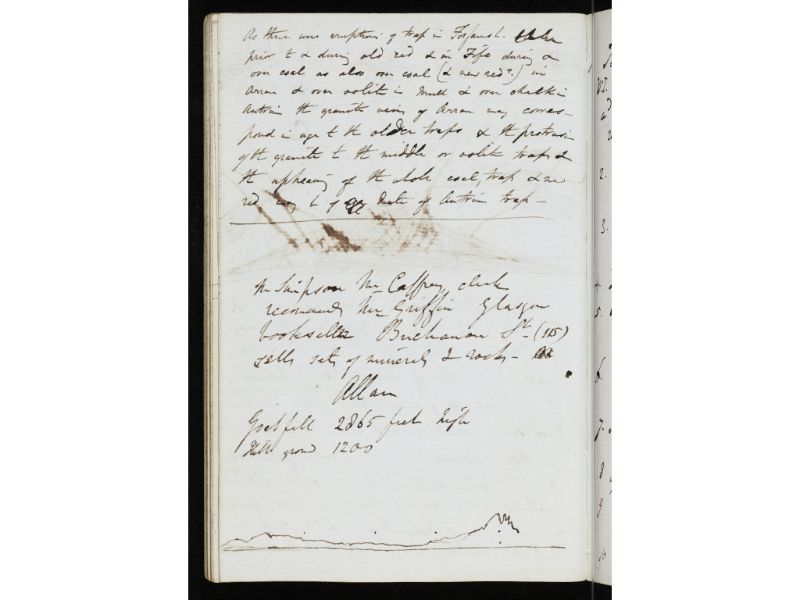

He then began an analysis of the geology of the island, posing questions, and offering amazing drawings.The pages of the notebooks are packed with details, almost at a breath-taking pace.

Lyell immediately made connections with what he saw in Arran with Forfarshire, Fife and Antrim, whilst taking the details of experts and mineral sellers resident in Glasgow, and making another simple line drawing showing the skyline of Goatfell.

By page 66 he is making significant notes entitled ‘Elements’, culminating in what appears to be the proposed structure of chapters for his book.

Wilson adds to the context of that trip; Mary met Lyon Playfair on the boat across – Andrew Ramsey later joined the party. Playfair accompanied Mary on the beach collecting shells, whilst Ramsey and Lyell geologised. At the end of their trip to Arran, the Lyells returned to Kinnordy until the 28th September. Wilson notes:

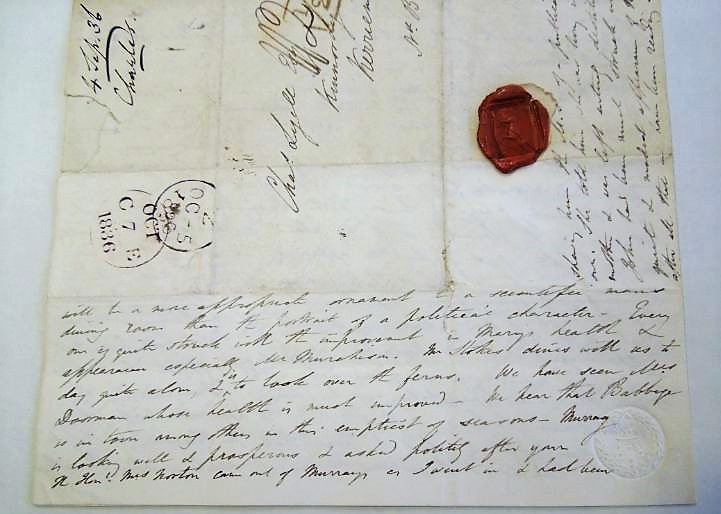

It was a long rest and summer vacation – a complete break from London, foreign travel and scientific meetings. During the preceding four years Lyell had worked through three editions of the Principles, three tours on the continent, one long trip through Sweden, and all the duties and demands of the foreign secretaryship and presidency of the Geological Society. Mary had acted in part as his secretary and assistant. She wrote many of his letters, helped to catalogue shells, and protected him from visitors. She had accompanied him on his excursions on the continent often under extremely primitive conditions; she had been abandoned in hotel rooms while Charles was off geologizing; she was often lonely. The vacation was for her too a chance to revitalise. When they arrived back at 16 Hart Street Lyell wrote to his father “Everyone is quite struck with the improvement in Mary’s health & appearance’.

I know Mary Horner Lyell as the daughter of Leonard Horner, who by setting up the Edinburgh School of Art in 1821 laid the foundations for Heriot-Watt College. It’s a small world. I am looking forward to being reacquainted with Mary, whose intelligent support to her husband is evidenced in the Lyell Collection by copious correspondence from when they first met.

Mary Elizabeth (née Horner), Lady Lyell

by Horatio Nelson King

albumen carte-de-visite, 1860s

NPG x46569

© National Portrait Gallery, London

I have not come across any mention of Ailsa Craig! However, I have found a reference to Kilmarnock, a topic for a future blog! Familiarisation – to some extent – achieved, it’s now time to decide priorities, to create projects, to engage with people, and to continue the aims of opening up the Lyell collection to all.