Using funding awarded by the Institute of Sedimentologists, Lizzie Freestone worked during the Summer of 2024 as the Charles Lyell Web Development Intern. Read on to learn all about her work, that combined metadata with Neolithic tools, and spanned teams from Digital Libraries, archives and museums, and included a particularly troublesome team member – Vernon!

Lizzie, with Dr. Gillian McCay of the Cockburn Geological Museum,

I started as the Charles Lyell Digital Collections Intern on the 3rd of June 2024. The goal was to develop processes so that specimens from the Charles Lyell collection, part of the Cockburn Geological Museum, could be more easily transferred into Vernon, the University’s collection management system for museum holdings. Once in Vernon, the specimen records can be automatically fed through to a more public-facing website, Collections.Ed; however, there are many significant steps required to get the data to that stage. Using processes developed by my line manager, Senior Systems Architect Scott Renton, my job was to connect that specimen data with high quality photographs of specimens taken by the University’s Cultural Heritage Digitisation Service, which are hosted separately on the University’s image hosting website, LUNA. Linking the specimen data to the images means that we could then have both the data and the associated images feed through to the public website.

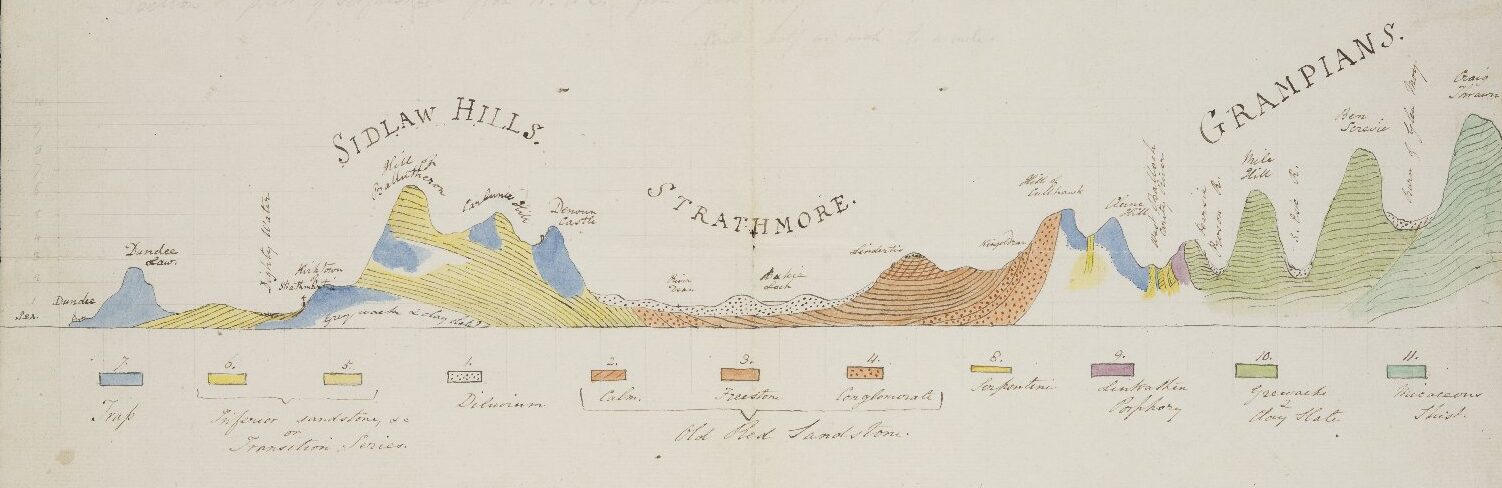

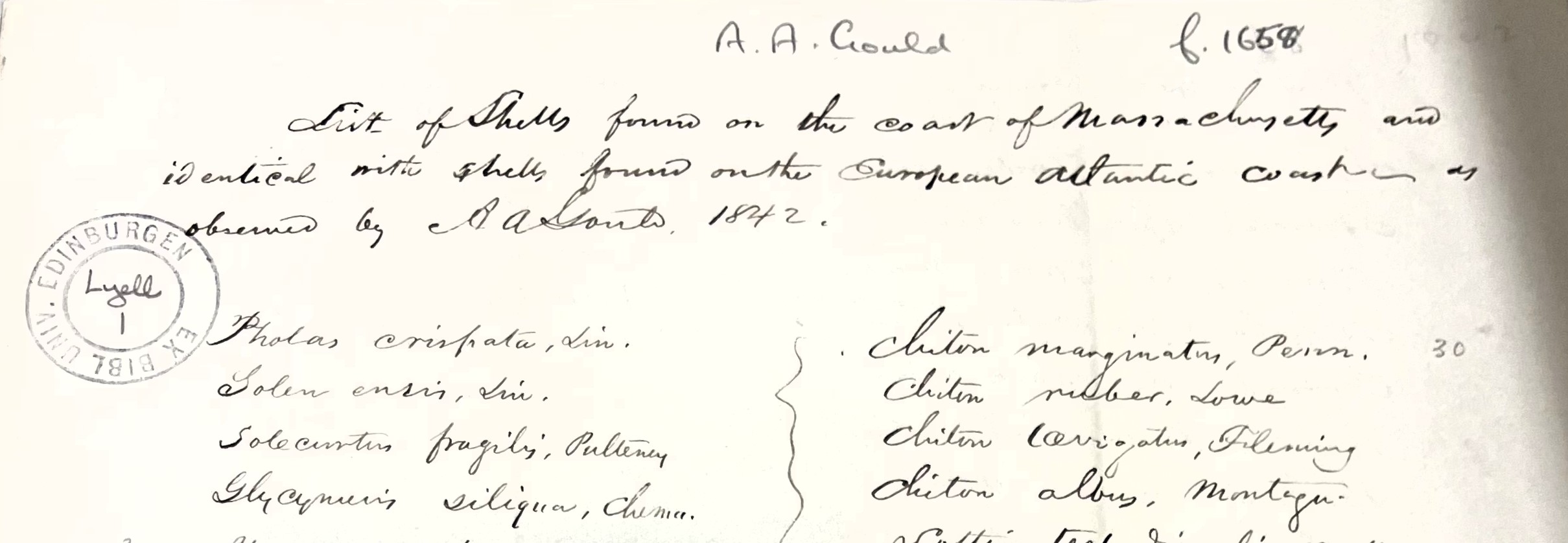

I began working on the images collection of the Cockburn Museum, which include around 200 teaching slides with a wide range of images including a series about an expedition to Spitsbergen, Svalbard; portraits of famous geologists; and photos of the natural landscape of Edinburgh, including Arthur’s Seat and the surroundings of Kings Buildings. Under Scott’s guidance, I learned how to run XML imports into Vernon. Working on batches of twenty or so records, I started getting to grips with the software and how it worked. Around this time, I also met with Gillian McCay, Curator of the Cockburn Geological Museum, who showed me the vast array of physical specimens the museum holds and explained the challenges of trying to get them into digital format. The Lyell specimens represent a complex set of records, reflecting their custodial history of nearly 100 years, so to get my eye in for more specifically geological specimens, I worked on drawers from the Currie collection, restructuring the spreadsheets and configuring Vernon to accept their contents. The Lyell specimens’ records have very long, complex descriptions – including research references, context, and loans – which would need to be broken down into distinct fields before they could go into Vernon. I spent a significant amount of time talking to Gillian and Pamela McIntyre, Strategic Projects Archivist on the Lyell project, about their thoughts on best ways to break up the description information, acceptable under Vernon’s demands.

Tear drop shaped flint tool. Dark grey brown colour, with some light grey to cream areas. The surface is covered by concoidal fractures, with little to no rind remaining. One glued label reading ‘ Sir C. Lyell’.

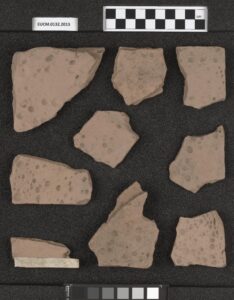

Rain marks in fine grained red sediment. One label attached to the sample reads ‘Rainmarks, Kentville’. One specimen has on its reverse a date, scratched into the mud, likely when still soft is written ‘July 21 1849’.

I found it really rewarding to work on specimens with such a long history and to get to talk so much with Scott, Gillian and Pamela, who all went above and beyond to answer my questions and concerns as they arose and to give me new ways to think about things. Learning how to use Vernon over the course of the summer was also really satisfying, as I went from zero knowledge to being able to use some of its most complicated functions, thanks to Scott’s explanations and a lot of practice. I also really enjoyed the opportunity to work as part of an IT development team and to have the opportunity to develop my technical skills. I was proficient in using Excel before, but had a minimal background in computer science. I now feel much more confident in learning how to apply new tools and to use programming to achieve a goal. Programming is now something I’m interested in doing more of going forward.

In all, I processed around 500 specimen records, of which around 150 were part of the Lyell collection. My work has developed processes for importing both new Currie and Lyell specimen records into Vernon including spreadsheet templates, setting up Vernon configurations, and created detailed guidance on to how to use them (including on how to set up and use new templates if needed). This means that getting further geological specimen records out of the basic excel spreadsheet stage, and into Vernon is much easier, which will make them more stable and more widely accessible. I also got to work on the Collections.Ed website, adding images and changing the ways some metadata was displayed, making the collections pages more visually appealing and navigable. It will take some additional technical work to get these specimens onto the new Lyell website (more details on that to come!) – for that, the team are using IIIF to link data and images – but it’s great to know that my work will support that next stage.

This internship has been a very rewarding experience, and I am really grateful to have had the opportunity to contribute to the digital preservation of these historically significant geology specimens. I’m looking forward to seeing how the digital collection grows over time!

Thank you so much Lizzie, Scott, Gillian – and Vernon! And thank you to the Institute of Sedimentologists – this funding has allowed us to fill a knowledge gap which will be of huge support to staff going forward – and has provided Lizzie with great work experience in a field outwith her main degree. This internship completes the final allocation of all the funding secured by the Lyell Project, with special thanks to David McClay, Philanthropy Manager, Library and University Collections, who has been its champion since the outset. As the project nears the final stages, forthcoming blogs will focus on access, discovery and legacy.