Lyell Summer Intern Harriet Mack on a visit to the Cockburn Museum to see their Lyell Madeira shells

We’ve been lucky to have had Harriet Mack, who is heading into her 3rd Year of a joint honours degree in Archaeology and Classics working with us as our Lyell Summer Intern! In this blog, Harriet shares her experience – which has included a lot of island hopping!

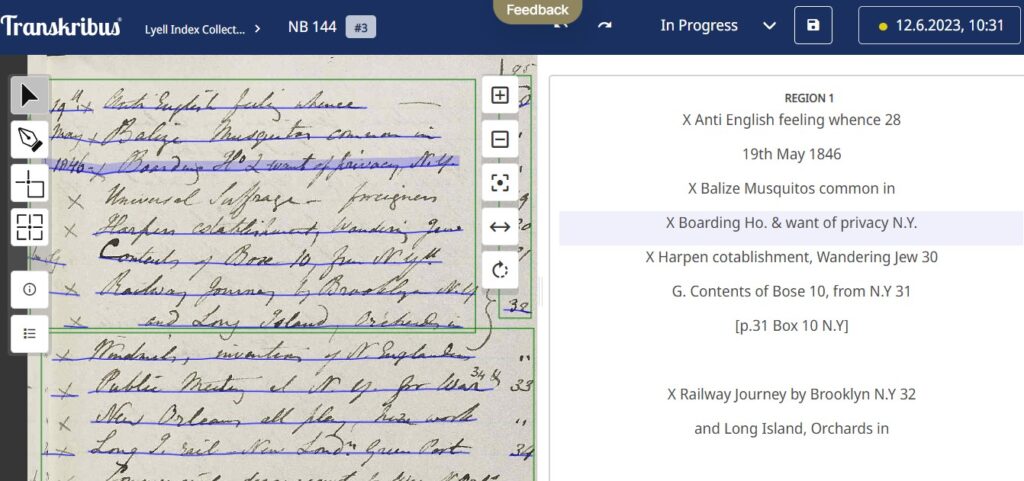

I first learnt about the Charles Lyell collection through a deep dive into Heritage Collections website, and I really liked the bright colours of the notebooks and the interesting handwriting. I then found the opportunity to volunteer with the Lyell project, cataloguing some of Lyell’s letters. I was captivated with the life and work of Lyell and his 19th century contemporaries, and started to gain an understanding of what transcription and palaeography were about.

Starting as Lyell Transcription Intern, I had to upgrade my palaeography skills, and Transkribus helped. Switching to their Lite version enabled me to view the information differently and really helped emphasize the difficult words.

Screenshot from Transkribus, Scientific Notebook 144 page 95

I was also able to join the other remote volunteers, Drew and Beverly, online, where we could work together, bringing multiple perspectives to Lyell’s work. Later, when I encountered more difficult issues like the Portuguese place names from the Madeira notebooks, we reached out to expert Carlos A. Góis-Marques who helped to bring context to some of the notebooks. Planning was crucial and I developed a plan that could grow with me, as my skills developed and improved. I could also follow the communal spreadsheet which enabled me to track my progress. I realised my notes also developed over time, even looking a bit like Lyell’s…

Extracts from Harriet’s own project notebook

Once I had developed my skills – it was time to set off island hopping! First stop east coast of Georgia, then the Isle of Wight, Madeira and the Canary Islands.

Notebooks 129 and 130 both cover Georgia, USA, focusing on some of the islands off the east coast like St Simons Island, and Pelican Bank. On these islands, I was introduced to Lyell’s geological observations particular to islands, the environmental impacts, fauna and flora, and historical contexts. In America especially, Lyell’s observations of the workings of the islands mix into his observations on slavery, race, and indigenous people.

I then moved on to Notebooks 212, 213, and 214, with some of the contents being based on the Isle of Wight – which is where I’m from, adding a layer of expertise. I know the places he stayed along the West coast, at the Needles, Freshwater Bay, and Hamstead. Lyell noted the difference in geological specimens and rocks either side of the chalk ridge of the island, allowing him to suggest that south of the ridge – with marine specimens – was part of the Paris basin and had been exposed to the sea. North of the chalk ridge he found land specimens suggesting that it was originally connected to the mainland of the United Kingdom.

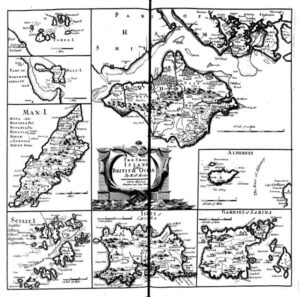

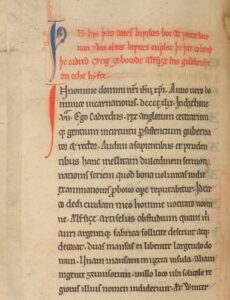

I wanted to know more about Lyell’s interest in the Isle of Wight, and took time to search more. I found that as early as Notebook 3 page 108-109, he notes reading about the Isle of Wight in Camden’s Brittania, leading me to find an online copy of the book and an early map. This really excited me as it gave an insight into what map Lyell could have used. I also established that Lyell visited the British Museum and consulted a Charter dated 949 AD. This charter told of King Eadred giving 1 hide (mansa) on the Isle of Wight to his gold and silversmith Ælfsige. This charter is one of the earliest primary sources I had seen, referring to the Isle of Wight as Vecta Insula, a Latin name given by the Romans.

Camden’s Britannia, : Newly Translated into English: With Large Additions and Improvements· Publish’d by Edmund Gibson, of Queens-College in Oxford. ProQuest, UMI, 1695. Print. Page 1048-1049

Isle of Wight Charter, MS Harley 436 f. 76v

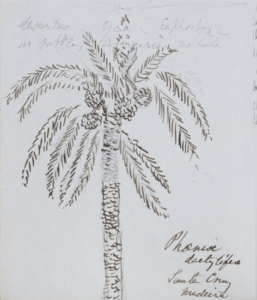

Lyell’s drawing of a Phoenix dactylifera, Madeira January 1854, Scientific Notebook 189 page 60

After looking into Lyell’s travels to the Isle of Wight, I hopped on to Madeira and the Canary Islands. Lyell’s study of these islands runs to 12 Notebooks dating January – August 1854, and contain his work alongside Georg Hartung (German geologist). I found they were more complicated, however, once I gained more context, I found they were the most enjoyable to work on. Lyell arrives in Funchal and the Notebooks relate his developing thoughts on formation and volcanic theory in response to his contemporaries such as Élie de Beaumont. The Notebooks include both geological and nature notes, with a large focus on shells and volcanic formations. One of my favourite drawings from this book is the Phoenix dactylifera (Date Palm). Lyell lists the shells he is collecting at Porto Santo and Madeira, such as Buccinidae. It was then really special for me to visit the University’s Cockburn Museum, and see some of their Madeira shells.

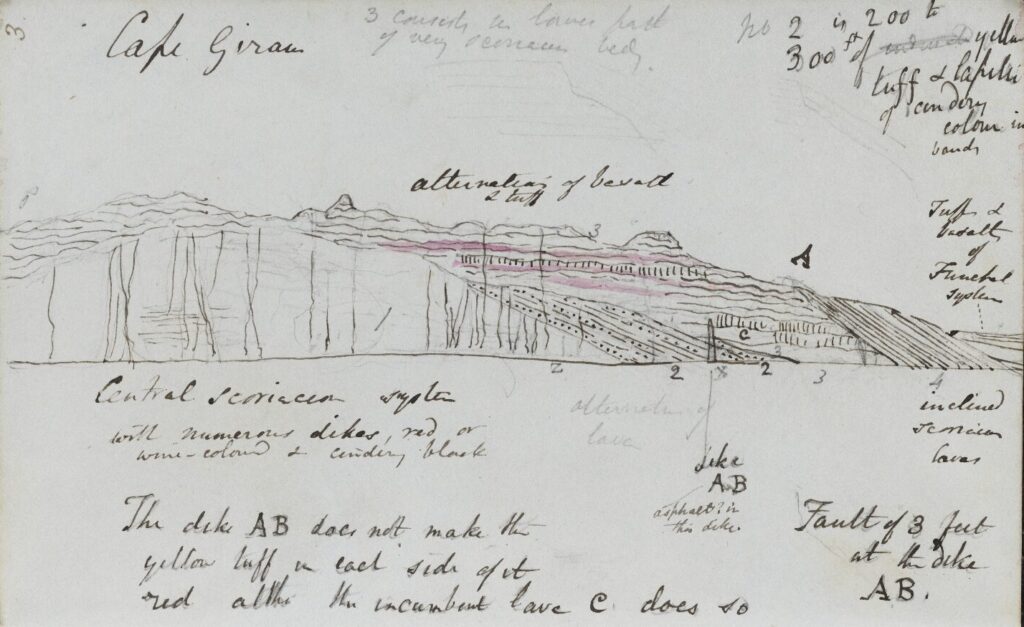

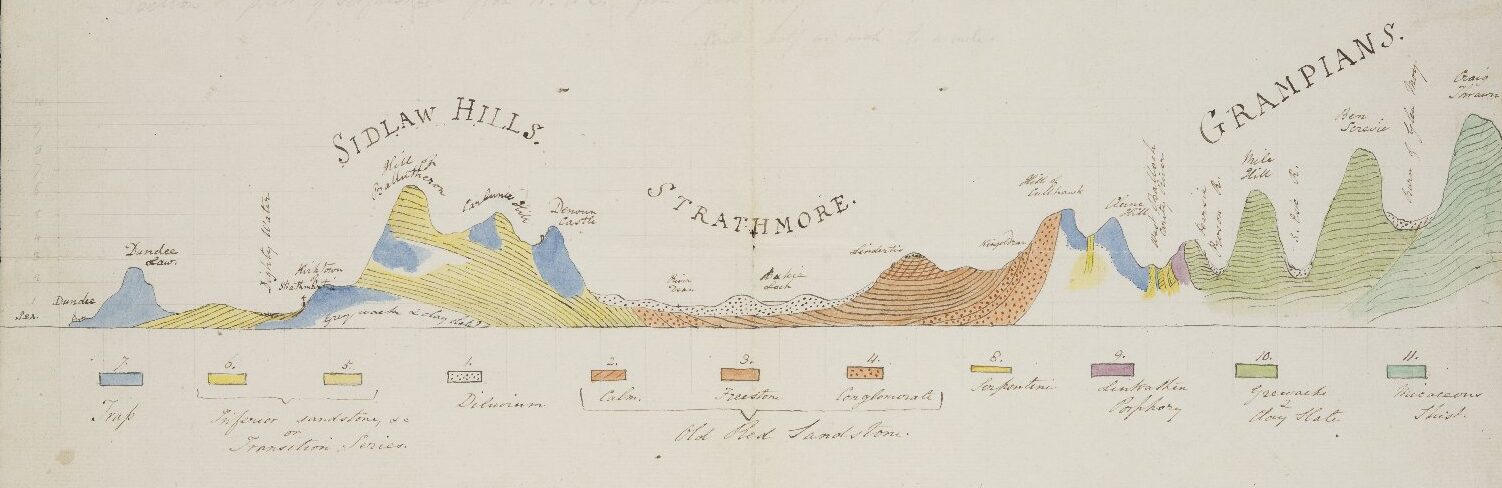

There are a team of people working together to write an upcoming exhibition on Lyell, and via my deep dive in Madeira, I was able to draw their attention to Notebook 191 page 3 and detailed sketches of Cape Girão on the south coast. This page stands out as having colour in-depth notes, and impressive detail. Its good to know this Notebook page will now be included in the exhibition.

Lyell’s drawing of Cape Girão, Scientific Notebook 191 page 3

I found that my place recognition was drastically improving. Google Earth was extremely helpful, revealing the terrain and magnitude of Madeira and the Canary Islands in 3D. This not only improved my modelling skills, but also unlocked an environment that was virtually unchanged from that which Lyell was observing. Using Cape Girão as a starting point, I could match drawings to Google Earth and established that Lyell’s sketch in Notebook 191 page 3 was most likely drawn at sea to give Lyell the fullest image of the cliff face.

Google Earth (Version 9.191.0.0), Cabo Girão, Madeira: Latitude: 32.6322222 Longitude: -17.00583333333333

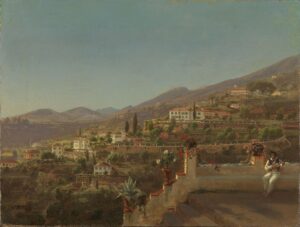

Whilst looking at the Madeira notebooks, there was a name that was repeated throughout that was initially unknown and difficult to decipher. That was until Notebook 191 p.110 where Lyell finally wrote the full name down as Johan F. Eckersberg, a Norwegian painter, who was in Madeira at the same time as Lyell, and as the Notebooks evidence, interacted and may have even advised Lyell’s sketches.

View of Funchal, Madeira. Johan Fredrik Eckersberg, 1854, Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, The Fine Art Collections, NG.M.03396

Eckersberg completed many paintings of Madeira, recording what the Island looked like whilst Lyell and Hartung were there. By connecting Eckersberg’s artistic realism to these geological travels, the landscape and environment can be better understood.

Notebooks 194– 195 cover La Palma and have some of the most recognisable landscape drawings. One that stood out to me was Lyell’s drawing of La Palma’s Caldera from Tazacorte. This one was much easier to locate on Google Earth as it had specific peaks, so I was able to be more accurate in terms of angles and direction.

Google Earth (Version 9.191.0.0), Tazacorte, La Palma: Latitude: 28.6475 Longitude: -17.92277777777777

Notebook 195 page 40, Lyell’s view of La Palma Caldera

Over 10 weeks, I have visited 7 islands with Lyell, and completed the transcription and summaries of 25 notebooks. This internship has really opened up my understanding of 19th century geology and Lyell’s contribution to this emerging science, as well as just how connected society was.

Thank you Harriet for all of your hard work during the Summer! By utilising both old fashioned tools – lists, note taking, reaching out to experts and finding contemporary sources and art – alongside 21st century ones such as AI and Google Earth, you’ve really been able to explore Lyell’s islands and make them much more accessible for the future!

connecting Eckersberg’s artistic realism to these geological travels ?

Link

yes! there’s a great project in there for someone!