My name is Claire Hutchison and I am very proud to introduce myself as the Lyell Project Conservator at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections. I am a Paper Conservator who has worked extensively across archives in Edinburgh on a number of archival projects. My work has led me to become a specialist in fragile formats, such as transparent papers, newspapers and wet press books. This is not my first time working at the CRC; I was lucky enough to be an intern in the conservation studio twice in my career.

I have learnt a lot about Lyell and his dedication to recording his findings since starting. It’s a very personal collection, and it’s clear that they were cherished by Lyell. The labels and indexes are beautifully written and constructed; one can only dream of having the same patience and dedication with their own notebooks. As a Conservator, I was also impressed to find examples where Lyell had hand sewn his index pages into the notebooks. It’s a wonderfully consistent collection which has been a pleasure to conserve. It’s also been made clear to me since starting just how sought after this notebooks are as requests have been flying in; researchers are keen to start connecting those dots across the collection.

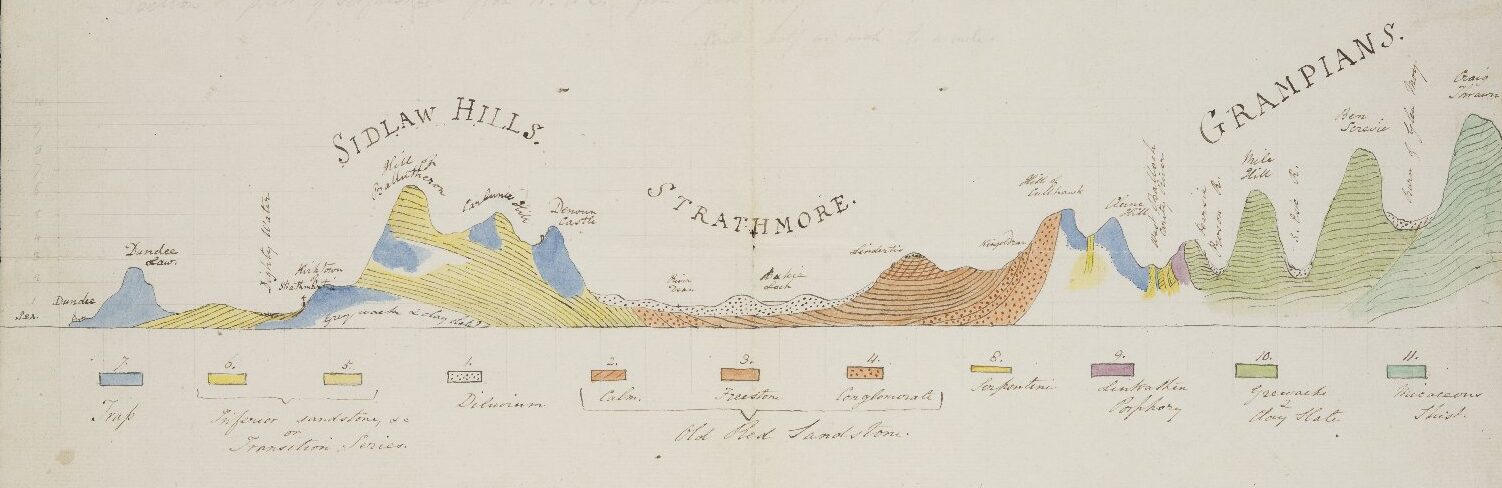

Conserving the Notebooks prior to digitisation was imperative in order to prevent loss or further damage to the bindings. The 294 Notebooks were in varying levels of condition, however, overall they were stable with very few requiring intense treatment. It was clear from the flexibility of the spines that they had been well used and heavily manipulated by Lyell on his travels. The adhesive Lyell used to apply his labels and covering material was starting to fail. The earlier Notebooks suffer from red rot – commonly found in vegetable-tanned leathers from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The leather will become dusty, and the fibrous structure will deteriorate, resulting in the damage or complete loss of the leather binding.

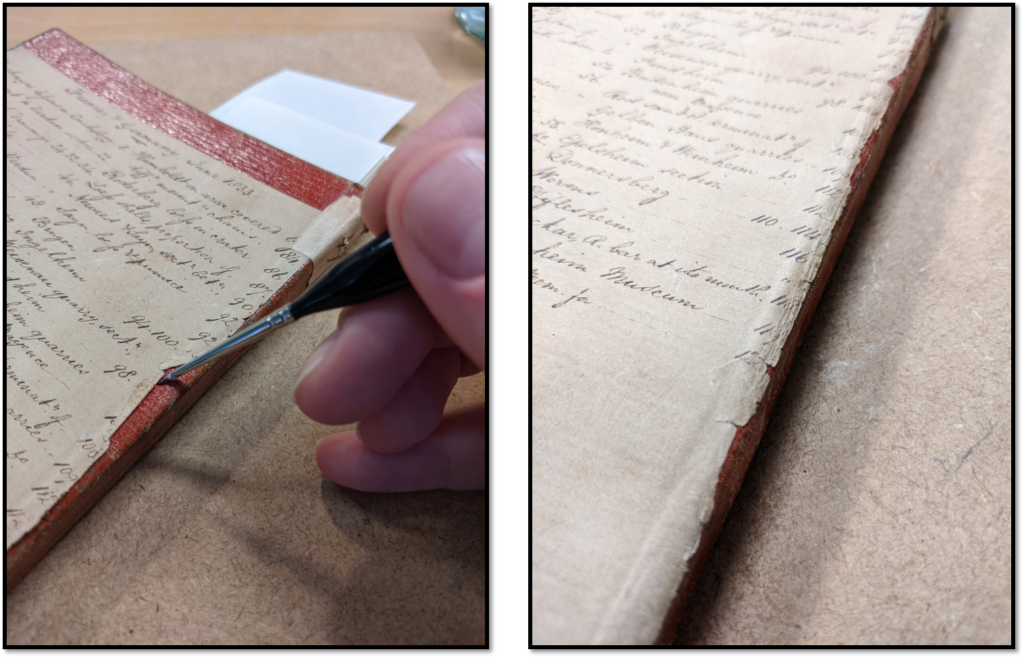

Reattachment of covering material before and after

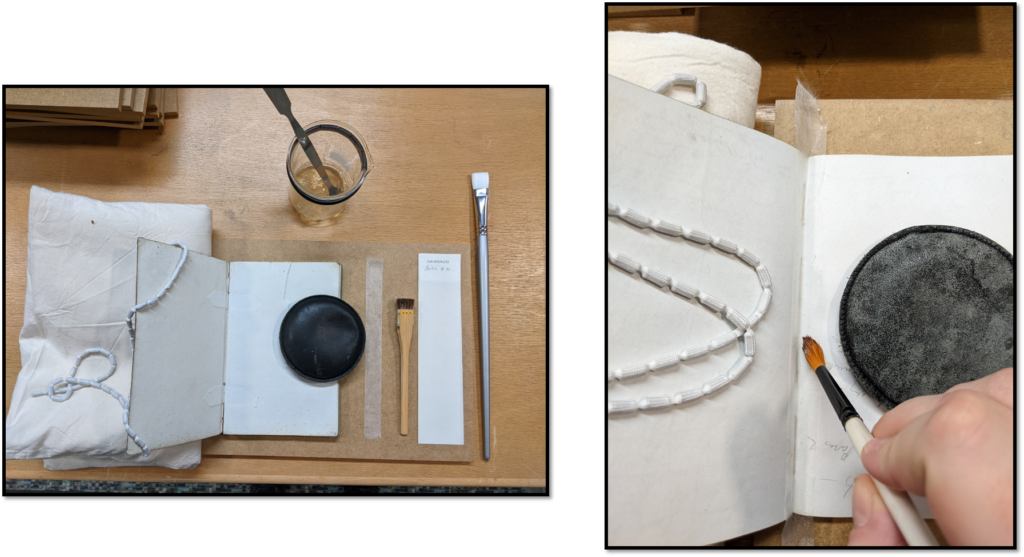

Internally, it was clear that Lyell had held and bent the spines to write into positions that had caused splits to form between the signatures of the text block. If not treated, these will worsen with handling and ultimately lead to loose pages or whole sections of the text block detaching fully from the binding. Lyell used either graphite or ink within his notebooks, so gelatine has been used to ensure that no bleeding or movement of the corrosive iron in the ink occurred. A strip of Japanese paper was applied to repair this inner joint and prevent further splitting (see example below).

Setup and attachment of inner joint repairs

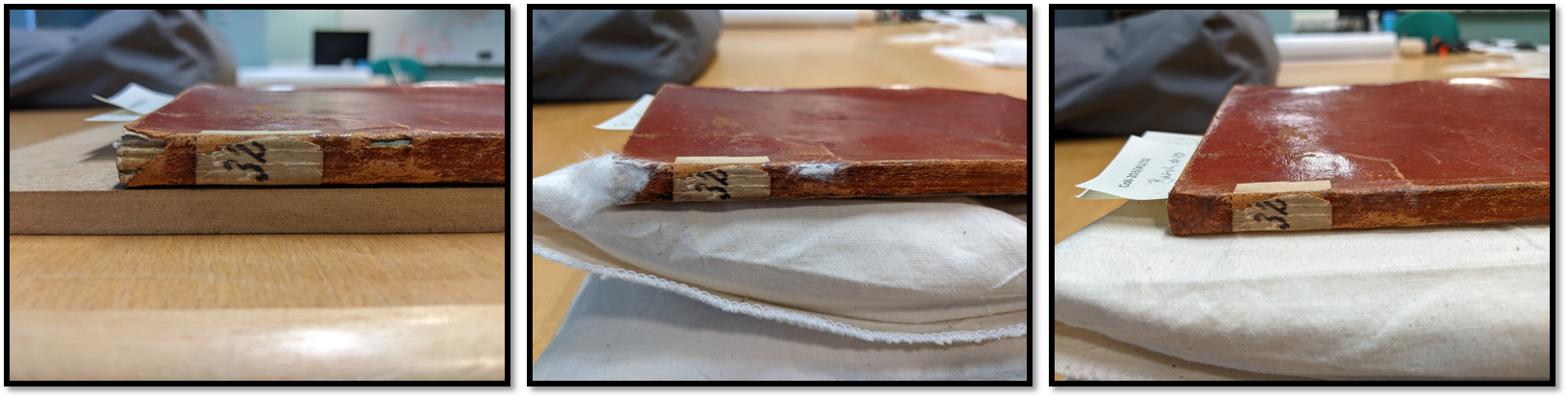

In some rare instances, further intervention was needed where parts of the spine were lost and the sewing was exposed. This required lifting back the leather of the boards either side of the spine and inserting a repair to stabilise the structure. Layers of Japanese paper were applied to the spine and built up to the required thickness of the leather. Then a final layer of toned Japanese paper was applied to the top, blending in with the rest of the spine piece.

Spine repairs before, during and after treatment

Thanks to generous funding from the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust, two 8-week interns have started working on the Lyell Project. They are helping to assist in the overall efforts of the project, but also have been given their own branch of the collection to work on. Sarah MacLean is currently working on the 1927 donation of letters of correspondence. Joanne Fulton has been given the task of rehousing Lyell’s collection of Geological specimens. This month, my work on the project will continue with the conservation and rehousing of the printed material in the collection, such as Lyell’s own copy of the ‘Proceedings of the Geological Society’.

Stay tuned for more conservation updates soon!