As I am now coming to the end of my time in Edinburgh cataloguing the papers of Professor Sir Godfrey Thomson, references aren’t terribly far from my mind! But I had some pause for thought after a conversation with my eighty-one year old Grandmother. While most of my Grandmother’s contemporaries now shop, talk, and bank online, she remains resolutely uninterested. When I explained I would never see my references – they would be e-mailed, uploaded, etc, my Grandmother was particularly disdainful.

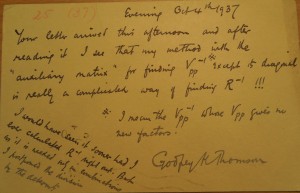

For once, I found myself rather agreeing with her. References were often treasured by the subject, years after they no longer had use for them. They were a courtesy, a kindness. While their primary function was to allow the receiver to gain further employment, they were also an acknowledgement of their hard work, and usually written by someone the receiver respected and admired. References are still, undoubtedly, all of these things – but now, of course, the subject rarely has a copy, and employees rarely keep them for any length of time.

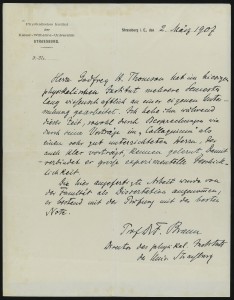

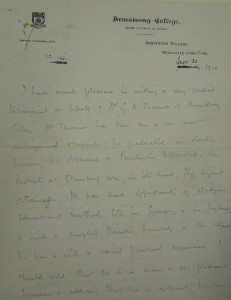

Thomson’s collection contains two – one from the Nobel Prize winning physicist, Karl Ferdinand Braun, and one from educator and historian of music, Sir William Henry Hadow:

Reference from Sir William Henry Hadow

Both are highly complimentary. Hadow describes Thomson as ‘one of my most distinguished students…a man of very pleasant manners and address…extremely popular in college’, and praises his ‘remarkable power of influencing others for good’.

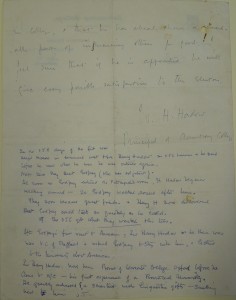

Hadow was Professor of Education at Armstrong College while Thomson was in turn a student then lecturer. Both had in common a love of music – Hadow frequently wrote on the topic, while Thomson was a skilled pianist. We know that both Thomson and Hadow were interested in the role that music could play in a liberal education, and Thomson’s lectures on teaching music survive in his collection. The notes written on the reverse of the reference are in Lady Thomson’s hand, and comment on Thomson and Hadow’s harmonious friendship and working relationship.

Braun was Professor of Physics at Strasbourg while Thomson was undertaking his DSc, supervised by Braun. He was an inventor, and experimented widely with wireless telegraphy. No doubt he would have been an exiting person for the young Thomson to work with, and it would appear the feeling was mutual – he describes him as well informed, and showing great ‘experimental ingenuity’.

Part of the reason these references meant to much to Thomson is because they were unique, and written in the hand of men whom he had a great deal of respect for. While archivists are widely encouraged to see the beauty in bit code as much as they can illuminated letters (a gross exaggeration on my part!) I’m not quite sure how this will translate in our current day record creation. Laying the ever evolving issues of digital preservation aside, references simply aren’t prescribed with long term value. Which is a shame, because however biased they may be (which they are supposed to be – they are, after all, the opinion of the writer!) they certainly tell us a good deal about the subject.

With thanks to Simone Müller and Christina Schmitz for their translations, and to Serena Frederick for pestering them for said translations!