For the last few weeks, I have been cataloguing the papers of mathematician, Walter Ledermann (1911-2009). The collection largely composes of highly mathematical letters from Thomson to Ledermann. Having the somewhat dubious distinction of failing mathematics twice, its fair to say I had misgivings!

My failure as a young mathematician was due in part to my ready dismissal of mathematics as a dull, dry, monotonous subject (but in the main, a serious lack of talent!). I remember somewhat haughtily telling my long-suffering teacher that I liked subjects about people. Mathematics, as far as I was concerned, lacked any humanity and any discernible art. How wrong I was.

Ledermann, a German-Jewish refugee, was more than used to such criticism being levelled at the subject – the art form – of his choice. In fact, he opens his autobiography, Encounters of a Mathematician, with the following:

Mathematics is a soulless occupation devoid of feeling and human values.

But that, Ledermann tells us, was never his experience:

I feel strongly that mathematics can and should form part of human relationships.

Ledermann grew up in Berlin, proving himself a talented violinist and mathematician from an early age. He loved music, and despite growing up in the midst of the depression, attended concerts regularly by any means possible. By the 1930s, the Berlin that Ledermann called home had changed rapidly, and he and his family were no longer welcome. It was his love of mathematics that gave him hope – despite the anti-Semitism he encountered, Ledermann’s ability, talent, and enthusiasm could be neither denied nor quashed. In fact, Ledermann’s talent for mathematics quite literally saved his life.

On completion of his degree at the University of Berlin in 1934, Ledermann won a scholarship created by students and citizens of St Andrews to support a Jewish refugee. He received a warm welcome from his fellow students, his lecturers, and the local community at St Andrews, and tells us: ‘it is no exaggeration to affirm that I owe my life to the people of St Andrews’ (Encounters of a Mathematician).

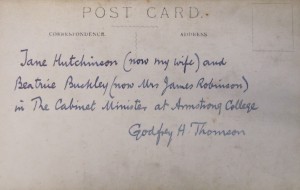

Ledermann completed his PhD after just two years, and found himself at the University of Edinburgh. This would be the start enduring friendships between Ledermann and the brilliant and troubled mathematician, A C Aitken, as well as Professor Godfrey Thomson.

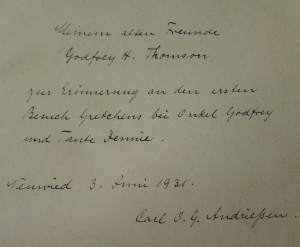

Ledermann quickly became Thomson’s mathematical assistant (or ‘tame mathematician’, as he puts it!), assisting him in writing The Factorial Analysis of Human Ability. Thomson and his contemporaries used Factorial Analysis to understand human differences (mathematics and humanity again!), and this is still a technique used by psychologists today. Thomson spoke to Ledermann in fluent German at their first meeting, much to Ledermann’s delight, and the working relationship was a successful one:

My work with Godfrey Thomson was inspiring, creative, and intimate. We met daily during the morning break at Moray House, where the Department of Education was situated. After we had briefly surveyed the progress of our research on the previous day, Miss Matthew, his charming and highly efficient secretary, brought in the coffee and some delicious buttered ginger bread.

The very intensity with which he pursued his ideas, was a great stimulus for me to solve the mathematical problems he had passed on to me. Godfrey Thomson did not claim to be a mathematician. Although he understood mathematical formulae when they were presented to him, he preferred to verify his ideas by constructing elaborate numeral examples from which the theoretical result could be guessed with some confidence.

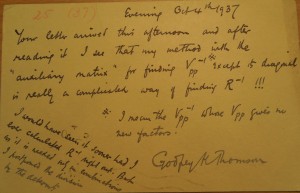

Sadly much of Ledermann’s replies to Thomson are absent. Thomson sends Ledermann pages and pages of calculations with explanatory notes, then his next letter will be one thanking Ledermann for the brief formula he has sent in return (Thomson at one point refers to Ledermann’s formulae as ‘very pretty’!). The letters also show the warmth of feeling between the two, with Thomson frequently enquiring of Ledermann’s family, many of whom were still in Germany, and telling Ledermann about his own family.

Ledermann treasured the letters. In a letter to Lady Thomson, who was attempting to write Thomson’s biography, he writes:

I have over a hundred letters from Sir Godfrey, written between 1937 and 1946, some of them short notes, others carefully worked out in the form of a research paper, with many interesting questions and illustrations. I greatly treasure the correspondence, not merely on account of its considerable scientific, and, may I add, aesthetic value, but also because it contains so many typical examples of that human warmth and sympathy for which Sir Godfrey finds a place even at the beginning or at the end of a mathematical letter.

Letter from Ledermann to Lady Thomson, Coll-1310/1/1/1/17

Ledermann returned to St Andrews after working with Thomson, and would go on to accept teaching positions at the University of Manchester, and the University of Sussex. His love of mathematics continued to endear him to students and fellow lecturers, and he continued to undertake revision lectures for students for years following his retirement. His wife, Ruth, was a social worker and therapist, and they retired together to London, where Ledermann passed away in 2009.

For Ledermann, the beauty of the equations passed between himself and Thomson were no different to the music of his violin – each displayed ingenuity and art. His love of mathematics was the source of the most satisfying ‘human encounters’ he had throughout his lifetime, and the correspondence between himself and Thomson serves as a reminder of the beauty and humanity of mathematics.

Sources: Walter Ledermann’s autobiography, Encounters of a Mathematician