Last week, we were pleased to welcome Professor Peter Fenton from Otago University, New Zealand, who was researching the work of A C Aitken. A deeply troubled and brilliant mathematician, Aitken was a phenomemal human calculator, with a photographic memory which could recall Pi to 1000 decimal places. His work impacted algebra, numerical analysis, and statistics. Additionally, he was a polyglot, a poet, a writer, and a violist.

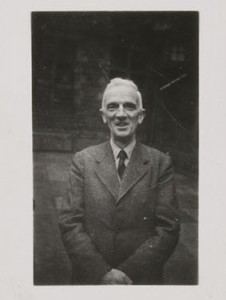

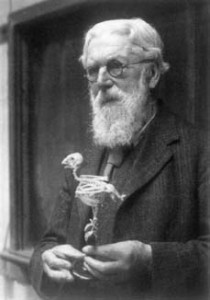

- Aitken in his later years

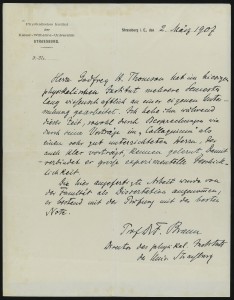

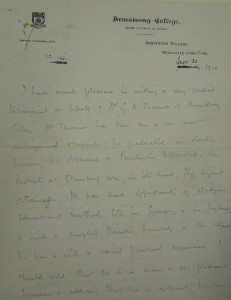

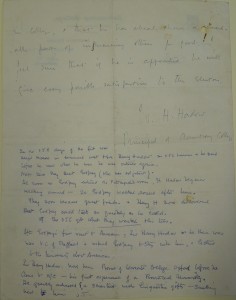

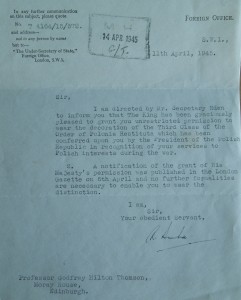

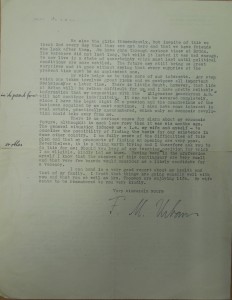

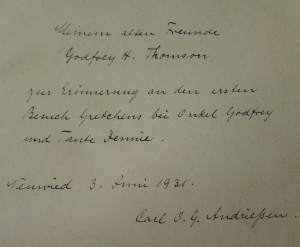

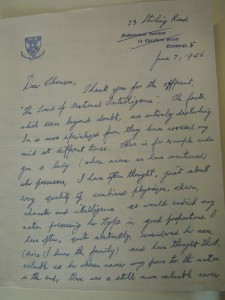

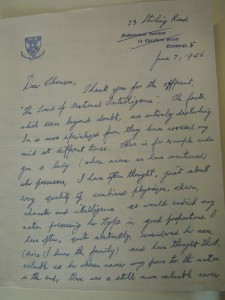

My interest was immediately piqued – always a fan of historical gossip, I had been intrigued when I discovered this letter from Aitken, who helped Thomson during the writing of his book Factorial Analysis of Human Ability, in Thomson’s collection:

Who was this lady who possessed ‘just about every quality of combined physique, charm, character, and intelligence as would enrich any nation possessing her type in good proportions’?! Aitken continues ‘valuable as her chosen career may prove to the nation, in the end, there was a still more valuable career of which the nation was being defrauded, partly, of course, through the blind crassness of men younger than ourselves’. I can forgive Aitken’s comments which suggest a woman’s biological capabilities should be valued over any others, since he is also rather unfair to his own sex! But I can’t help but wonder who this nameless, charming lady is – or just what Aitken and Thomson ‘mentioned’ about her in their previous discussion!

Alexander Craig Aitken (1895–1967) was born in Dunedin, in Otago, New Zealand. He was an exceptional student, winning several class prizes and graduating top of his class. His Father, who was a shopkeeper, allowed Aitken to do the accounts from an early age – this he enjoyed, and often credited his later mental arithmetic skills as stemming from this period. In 1913, he was awarded a full scholarship to attend Otago University, studying mathematics and languages (Latin and French). His experience of mathematics at University was unpleasant, although he met his future wife there, a brilliant botanist credited with establishing the Botany department at Otago.

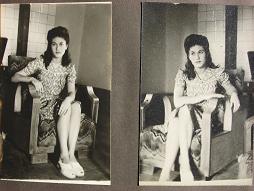

Winifred Aitken

Winifred Aitken

Aitken’s studies were interupted by the First World War, and he enlisted in 1915 at the age of 20. He documented his experience of the War in his book, Gallipoli to the Somme. It was first drafted in 1917, but Aitken’s published version was re-edited in 1962. Aitken’s account is at once harrowing and moving, as can be seen when he describes a friend’s death:

Two or three yards beyond this pair we found Harper lying, his thigh badly fractured, but calm and in full possession of his senses. We asked if it was very bad. He simply said: ‘I think I’m done for’…he spoke quietly, with the same high calm, far beyond his years – he was, I suppose, my own age, twenty-one, perhaps twenty-two – and he knew better than we, for he had lost too much blood and died of wounds a week later. He was of very heavy build and we could not move him an inch without causing him pain; but at that moment I caught site of a group of men, carrying a stretcher with them, coming through the gap and towards the trees. It was a volunteer party lead by Captain Hargrest, always the first to think of his men, and including Sergeant-Major Howden (killed at the Somme, 27th September 1916), Sergeant Carruthers (killed at Paschendaele, 12th October 1917), and Sergeant Frank Jones (died of wounds received at the Somme, 22nd September 1916). These men laid Harper on the Stretcher and carried him in, I following as dawn was breaking.

Gallipoli to the Somme p.103

Aitken c.1915

Throughout the war, Aitken carried a cheap violin, deriving comfort from the art he had learned as a child from a blind violinist who guided his playing through touch and ear. Such luxuries were prohibited – space in the trenches was extremely limited, but Aitken’s comrades took it in turns to hide the contraband instrument.

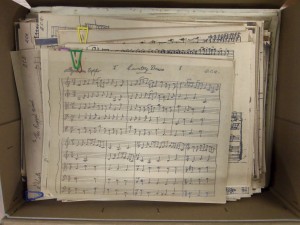

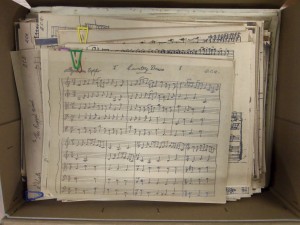

Aitken’s music manuscripts, many of which are his own compositions

Aitken sustained wounds to his arm and foot in 1917, which ended his army career. He returned to Otago, completing his studies, and becoming a mathematics master at his old school, Otago Boys High School. In 1923, he gained a postgraduate scholarship to study under Sir Edmund Whittaker. During his studies, his wife fell pregnant with their first child, and Aitken, feeling the full weight of his financial, familial, and academic responsibilities, began to feel physically and mentally ill.

His research was not prospering, and he feared he would be unable to submit his thesis on time. Months of frenzied calculations followed, cultimating in weeks of illness Aitken describes as being ‘like food poisoning’. Following his recovery, Aitken set about his thesis, and found the solution to the problem instantameously, submitting his thesis (by his own admission) hurredly. The thesis was awarded the DSc rather than PhD, an honour which AItken modestly describes as ‘a surprise’.

A fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh at the age of thirty followed, as well as the society’s highest honour, the Gunning Victoria Jubilee Prize. In 1936, Aitken became a fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1936; and in 1946 the chair of Pure Mathematics at the University of Edinburgh. For a short time during World War II, he also worked at Bletchley Park, though this part of his life remains a mystery.

Some of the many cuttings showing Aitken’s achievements

These achievements were overshadowed by his breakdown in 1927. Aitken, who had had something of a prepensity for mysticism from an early age, had been subject to hallucinations throughout his life. These began to intensify:

Clermiston Road, which leads up Corstorphine Hill to Clermiston Avenue, would suddenly twist in front of me; the branches of trees, full of the foliage of June, would suddenly become drenched with the heaviness of some further dimension, arresting, symbolising something, apocalyptic. The world “apocalyptic” is the only one by which I can describe the moonlight, the sycamore tree at nightfall, the further Pentlands, the edge of the skyline at Curriehill, which often seemed fringed with fire; and I could not see that this fire was the fire of my own nerves.

To Catch the Spirit, p.90

‘The fire of his own nerves’ would plague him throughout the rest of his career, ordinary women would look like angels and he would see indescribable colours. His wife, who had long since given up her distinguished work, devoted herself to looking after Aitken. This, according to their daughter, Margaret Mott, she did not grudge, fully believing in Aitken and his abilities. He spent much time towards the end of his career campaigning against decimilsation, his zeal eventually attracting ridicule, and died in 1967.

In his excellent introduction to Aitken’s memoirs, compiled from papers in the possession of his daughter Margaret Mott, Fenton tells us the title derives from ‘a letter taken up with the proof of a certain theorem, which Aitken signed ‘Q.E.D and A.C.A’ (ad captandam animam=to catch the spirit of the thing)’ (To Catch the Spirit, p.7). The title is a wonderfully evocative one, especially fitting in light of the following passage:

I believe we are surrounded the whole time by marvellous powers, are immersed in them, closer than breathing,and I think that all great music, poetry, mathematics, and real religion come from a world not distant but right in the midst of everything, permeating it.

To catch the spirit, p.23

Numbers, and Aitken’s intrinsic gift of understanding them, were ‘the spirit of the thing’, allowing Aitken to view the world around him in a way no one else could. In his review of Aitken’s memoirs, Wimp asks if any of us would choose to have such an incredible gift in light of the terrible price it comes with. I end with what I would imagine Aitken’s reply to be, from a passage regarding his breakdown:

It is customary to pass quickly over such an experience, as an illness,a regrettable pathological interruption in a career otherwise uniform, a passing spasm of suffocation. When I consider the great gain of experience, the widening even of personal sympathies, the sudden openings onto a hundred vistas unsuspected before, the emergence of new standards in literature music and painting… I could not but regard my own breakdown of importance…for since that time, there is not a tree, not a turn in a road, nor a hilltop, not even a swaying reed, but speaks of the beauty, the at first terrible beauty and mystery of the world.

To Catch the Spirit, p.94

Sources:

Aitken, A C, To Catch the Spirit, with an introduction by Peter Fenton, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1995)

Aitken, A C, Gallipoli to the Somme, (London: Oxford University Press, 1963)

Wimp, Jet, accessed 27/09/2012

Oxford DNB

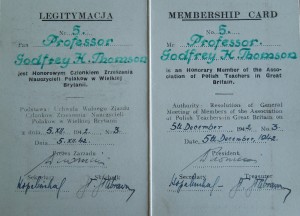

(Coll-1310/1/7 Papers Regarding Hectors Development)

(Coll-1310/1/7 Papers Regarding Hectors Development)