In 1936, Julia Stephanie Evadne McGregor was in the final year of a five-year medical degree and showed all the signs of a highly motivated and conscientious student who would do well. In January 1936, she was admitted to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, again in May and then June. She died on 4th July of rheumatic fever. On the anniversary of her death this year, the University is awarding a posthumous degree, with her family in attendance.

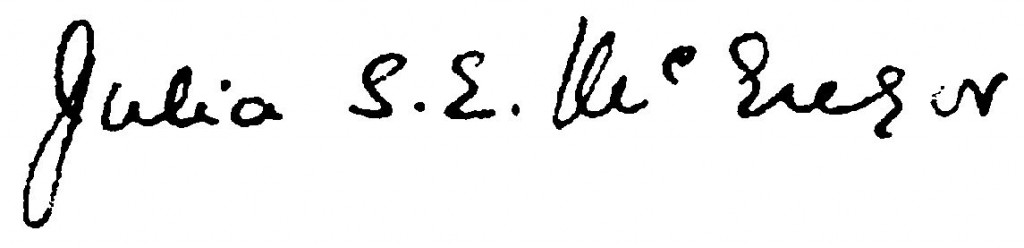

Stephanie (as she was known) was born in Gayle St. Mary, Jamaica on 9th April 1911, the daughter of Peter James McGregor and his wife Julianna Drucilla Marsh. She attended Wolmer’s Girls High School in Kingston, Jamaica from 1923-1929 and matriculated at the University of Edinburgh to study medicine in April 1931, having obtained her matriculation certificate at the University of London the previous August. On 21 October 1931 she registered as a student member of the General Medical Council.

Her first year of study saw her study under (amongst others) Professors James Hartley Asworth (Zoology), George Barger (Chemistry) and William Wright Smith (Botany), passing her first professional exams in 1932. In her second year her Professors were Edward Sharpey-Schafer (Physiology) and James Couper Brash (Anatomy). She passed her second professional exams in 1933.

In October 1933, Marjorie Rackstraw in her capacity as Adviser of Women Students, wrote to Professor Sir Sidney Smith, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, informing him that Stephanie was in financial difficulties, having received no allowance since the previous August, due to her family being in financial difficulties themselves. As a result, she was able to gain an award of £25 from the Medical Bursaries Fund. By the following February, this plus money Stephanie had managed to raise elsewhere was once again exhausted and Miss Rackstraw wrote again to Prof. Smith to explore other options, specifically a loan

She described Stephanie as capable and sensible, “one of the best of her class and has gained merit certificates in four of her subjects and one prize in Botany”. The letter also recorded that Stephanie was planning to apply for a Vans Dunlop Scholarship and, “if the banana harvest is satisfactory she should be able to meet her expenditure during the next two years”. A further grant of £50 from the Medical Bursaries Fund was awarded.

Further troubles arose in late 1934. On 29th October Miss Rackstraw wrote again to Prof. Smith, explaining that Stephanie’s father had died a few weeks earlier, presenting more financial problems over and above dealing with the bereavement. She was to receive further small pots of money.

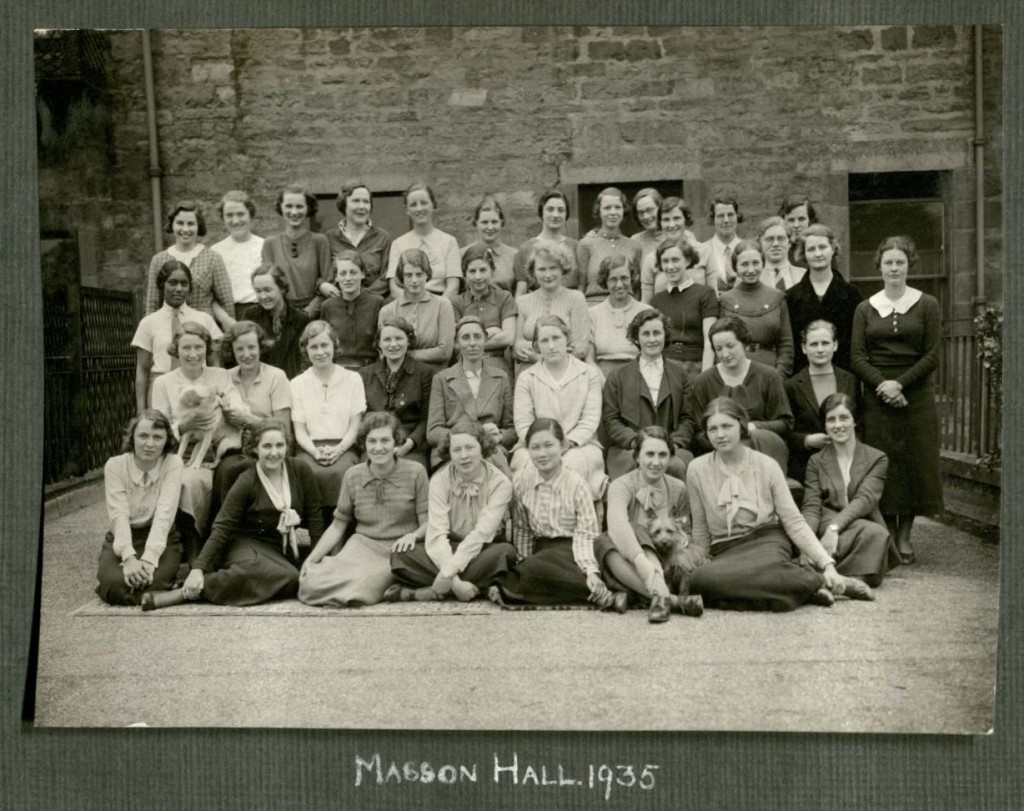

By 1935, Stephanie was living in Masson Hall of Residence, where Marjorie Rackstraw was warden. The building no longer exists, having been demolished in the 1960s to make way for the Main Library building. However there are extensive records, including photographs, and one that includes Stephanie survives.

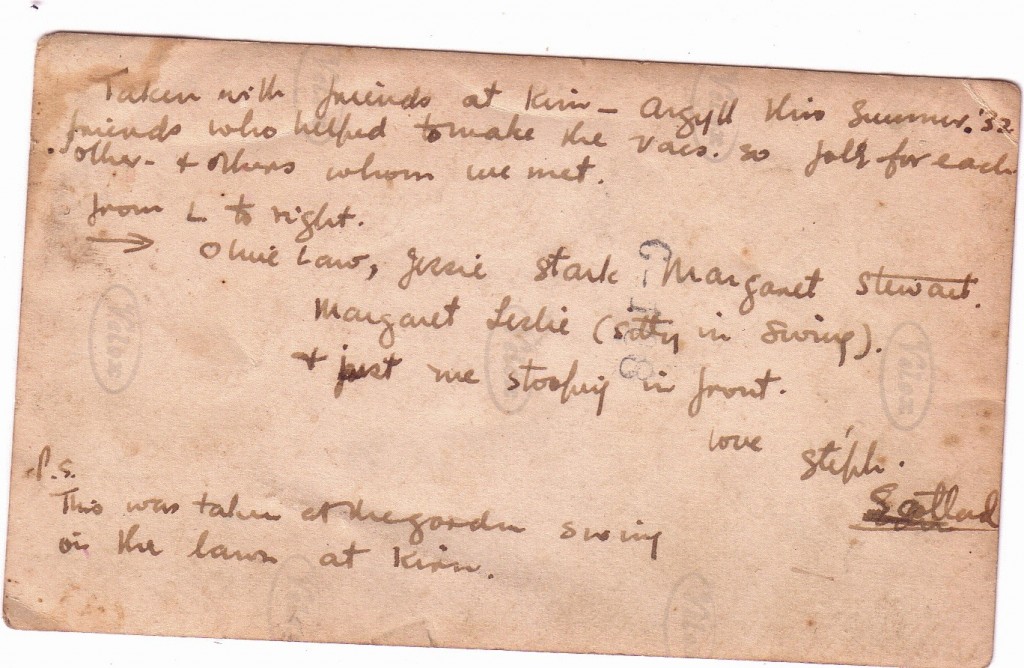

1936 did not start well for Stephanie. She fell ill on the 17th January and ended up in the Royal Infirmary but was let out after 15 days on the condition that she go away for convalescence. She went to say with a Mrs Corrigall at “Stromness, Kirn, Argyll”, but the ordeal journey there resulted in a week in bed and further time away from study. She wrote to Prof. Smith to explain her situation.

Mrs. Corrigall, with whom I am staying, called in her family Doctor and I have been under his care ….. I am still quite unfit to face classes and work ….. I am very troubled about my attendance and classes ….. This is the first time in the five years of my academic life, Sir, that I have for any reson or other been forced to miss my classes

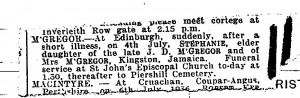

On 5 July 1936, Marjorie Rackstraw again wrote to Prof Smith but this time she was not looking for financial assistance. Instead she had the task of informing him that Stephanie had died the day before, a victim of “rheumatic fever following tonsillitis which affected her heart”. Her funeral was held at St. John’s Episcopal, where she had been a member of the congregation, and she was buried at Piershill Cemetery.

Since the later 19th century, women students had been battling to gain parity with their male counterparts. It was not until the 1890s that women were able to matriculate as students and it was only in 1915 that they gained an equal status to men within the Faculty of Medicine. Even by the time Stephanie was studying, numbers of female students were very small compared to men, having only just edged over 10%. Had Stephanie graduated, she would have made up one of only 19 women who were awarded a degree of MBChB that year. Although she probably never saw herself as such, Stephanie can be seen as a contributor towards a major change within medical education, paving the way for those who followed.

At the graduation ceremony which takes place on 4th July 2015, coincidentally on the 79th anniversary of Stephanie’s death, the University of Edinburgh is awarding her a posthumous degree.