III – IN THE HUGH MACDIARMID COLLECTION…: MS LETTERS AND OTHER MATERIAL RELATING TO THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION of ANIARA BY MACDIARMID AND ELSPETH HARLEY SCHUBERT, 1963

![]()

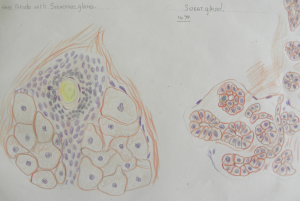

13 October 2016 sees the 60th anniversary of the publication of Aniara by the Swedish Nobel Laureate Harry Martinson (1904-1978)… Sweden’s pioneer of the poetry of the atomic age. Published by Bonniers, Stockholm, in October 1956, the full title of Martinson’s work was Aniara: en revy om människan i tid och rum. An English translation, or adaptation rather, by Hugh MacDiarmid (1892-1978) and Elspeth Harley Schubert (1907-1999) was published in 1963 as Aniara, A Review of Man in Time and Space.

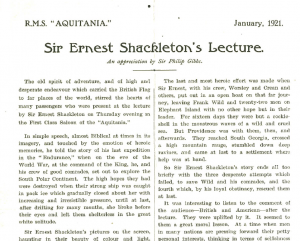

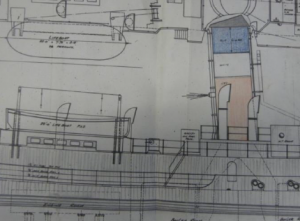

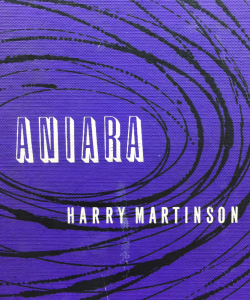

Front board of ‘Aniara’ translated from Swedish by MacDiarmid and Schubert, 1963 (Shelfmark PT 9875.M35 Mar, but also available through Special Collections, CRC).

With a libretto by Erik Lindegren (1910-1968) based on a shortened version of Martinson’s poem, an opera by Karl-Birger Blomdahl (1916-1968) – also called Aniara – was premiered in May 1959 at the Royal Opera (Kungliga Operan), Stockholm, and was also presented at the Edinburgh International Festival in 1959. In 2013, the work was again expressed in the Edinburgh Festival through a re-imagination by Opera de Lyon of Beethoven’s Fidelio melded with Aniara.

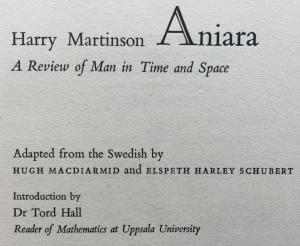

Title-page of ‘Aniara’ translated from Swedish by MacDiarmid and Schubert, 1963.

The subject of the poem is a spaceship (or goldonda) called Aniara. This future spaceship is carrying 8,000 refugees or emigrants – ‘forced emigrants’ – from a radiation poisoned Earth (called Douris in the poem) which is to become quarantined.

‘…Earth must have a rest

for all her poisons, launch her refugees

out into space, and keep her quarantine…’

Originally bound for Mars and on one of its routine flights – ‘all in the day’s work as it seemed’ – the spaceship ‘was singled out to be unique and doomed’. Aniara is thrown off course by the asteroid Hondo, which ‘jerked us off route’, missing Mars and bypassing its orbit.

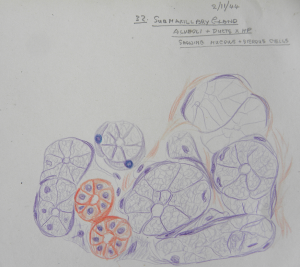

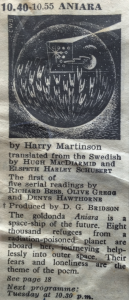

Graphic used to accompany the short ‘Radio Times’ resume of ‘Aniara’ broadcast on the BBC Third Programme in November 1962 (Copy at Ms. 2973-2974).

Out of control and pulling away from the solar system towards outer space, Aniara is finally thrown onto a course pointing to the star system of Lyra, ‘and no change of direction could be thought of’. The 8,000 occupants realise that they are doomed to an endless journey to nowhere.

‘In the sixth year Aniara flew on

with unbroken speed towards the Lyra…’

(Canto 13)

Having lost all ties to their past and with no hope of a future, their fears, bitterness and nostalgia set the mood for the poem. It offers a prophetic foresight of what we all might expect from nuclear warfare and its aftermath. Through Mima – a deity assuming the role of group-conscience to the voyagers, a device merging artificial intelligence with galactic wifi – a kind of electronic brain (using the terminology of a 1962 article in the Radio Times), a brain which ‘shows it all’, the occupants of the goldonda witness the destruction of Dourisburg, ‘the mighty town which once was Dourisburg’.

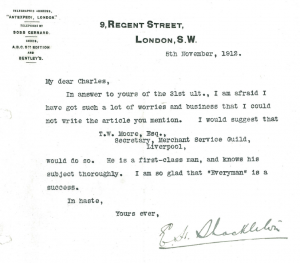

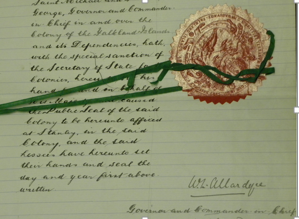

The short ‘Radio Times’ resume of ‘Aniara’ broadcast on the BBC Third Programme in November 1962 (Copy at Ms. 2973-2974).

Martinson’s work written in 103 Cantos (or songs) carries yet more of its own vocabulary. Canto 2 refers to the spaceship’ s gyrospiner and how it tows her up to the ‘Zenith’s light where powerful magnetrines annul Earth’s pull’…. the gyrospiner being, according to MacDiarmid’s notes, ‘a kind of propeller, possibly something like a helicopter’, and the magnetrine a ‘machine of the future which annihilates the power of the gravitational fields’.

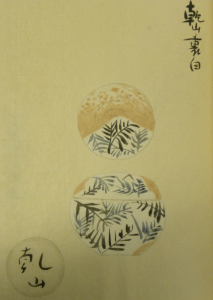

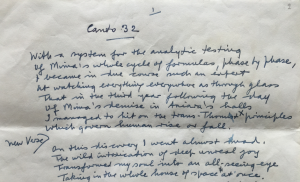

References to Mima, in Canto 32. (Manuscript in Gen. 894).

In Canto 15 we are introduced to gammosan – a drug relating to gamma rays – used on one of the emigrants, ‘pale and scarred by radiation burns’, who ‘very nearly fluttered away but was hauled back each time’. In Canto 26 we meet the phototurb – or nuclear bomb – in which ‘total mass is transformed to light quanta’.

‘…souls were torn apart

and bodies hurled away

as six square miles of townland twisted

themselves inside out

as the Phototurb destroyed

the mighty town…’

(Canto 26)

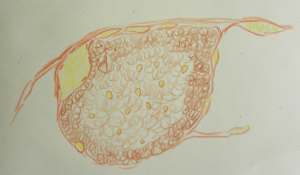

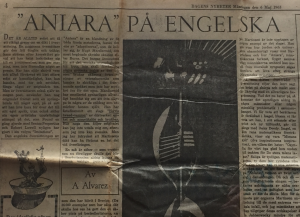

Mima, as illustrated by Sven Erixson (1899-1970) to accompany an article written by Alfred Alvarez printed in ‘Dagens Nyheter’, 6 May 1963. Erixson had been involved in decor and costume sketches for ‘Aniara’, the opera, in 1959. (Copy of article at Ms. 2973-2974).

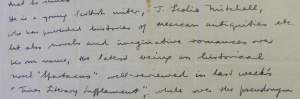

In October 1959, and only a few weeks after the staging of Aniara the opera at the Edinburgh Festival, MacDiarmid had been approached by the publisher Hutchinson with a view to ‘getting out an English version’ of the poem. The initial approach emphasised a smaller version of the poem… ‘the self-contained first twenty-nine cantos’ which had been published as Cikada (1953). MacDiarmid is asked if he would ‘consider taking on such a task’ in a rendering that ‘would have to be pretty free’ and ‘done by someone who is in his own right a poet of the first quality’. By November 1959, MacDiarmid had been informed that there was ‘in London happily a completely bilingual Scots-Swede who could collaborate’ with him in the task… Elspeth Harley Schubert.

![]()

By February 1960, Hutchinson had concluded an agreement with Bonniers of Stockholm for a publication of Aniara in English, and that rather than working on ‘only the first twenty-nine cantos’ MacDiarmid and Schubert would be funded by the Council of Europe sharing French Francs 416,000 for a translation of ‘the whole poem’. MacDiarmid’s share was to be French Francs 208,000 (or £150 sterling). Correspondence in the MacDiarmid collections in CRC indicate that work had begun certainly by March 1960.

![]()

By May 1960, the publisher was hoping that MacDiarmid might find the time to let them know ‘how things seem to be shaping’ albeit acknowledging the difficulties of ‘collaboration’ and the ‘technical problems which must be involved’. The imminent performance of Ariana, the opera, in London, in autumn 1960, was intimated too, and that while the translation ‘can’t possibly’ be completed, printed and published by then, it might be ‘wise to have it on the stocks as soon as possible’. In March 1961 however there was still no typescript in spite of promises from MacDiarmid in January to have it sent ‘very shortly’.

![]()

In May 1961, Hutchinson acknowledged MacDiarmid ‘for the completion of Aniara‘ and expressed agreement with him ‘that there should be a brief introduction’ to the work. By August, Martinson had offered ‘some interim notes’ and Schubert and Martinson were ‘to incorporate their suggestions in the typescript’. For her part, Schubert writing from Sweden in October 1961 expressed to MacDiarmid that she found his treatment of her own original translation ‘very liberal and sensitive’. On the matter of an introduction, she suggested that a foreword be written by ‘a Swede who knows the whole background, and is also an expert on the terminology and on natural science’. She recommended Martinson’s biographer Dr. Tord Hall (1910-1987), mathematician, professor and author, of Uppsala University.

A year later, in May 1962, MacDiarmid had been sent the ‘printers’ marked proofs of Aniara together with the manuscript’ for him to ‘go through immediately and make any corrections’. The English language translation was released in February 1963, though readings were aired by BBC Radio in 1962.

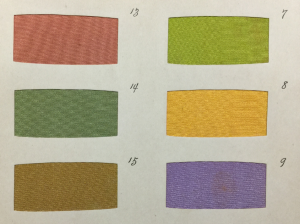

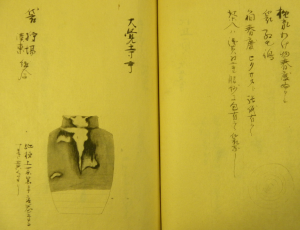

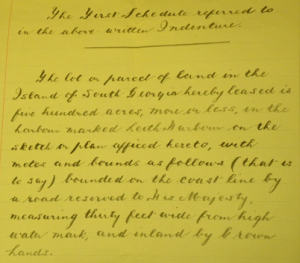

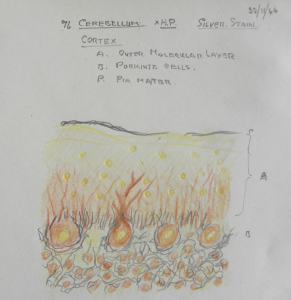

Article by Alfred Alvarez in ‘Dagens Nyheter’ which was critical of the MacDiarmid/Schubert translation. (Copy of article at Ms.2973-2974).

In the national Swedish daily – Dagens Nyheter – on 6 May 1963, the English poet and critic Alfred Alvarez (b. 1929) wrote a rather critical piece about the MacDiarmid and Schubert translation. Olof Lagercrantz (1911-2002) Swedish writer, critic, literary scholar and publicist provided a commentary to the Alvarez piece in the same paper. Alvarez writes that MacDiarmid, ‘the most talented Scottish poet after Burns, […] has achieved a kind of Harris Tweed version of the poem… simple, unpretentious and serviceable’. Alvarez is ‘under the impression that Martinson’s poem may have lost a lot in translation’. Following up on the Alvarez piece, Lagercrantz comments that, as far as Swedish readers of the translation are concerned, it is ‘perhaps especially remarkable to hear Martinson characterised as grimly devoid of humour. Such an astounding opinion has to have its roots in the translation’.

One thing Alvarez is certain about is that ‘the English translation that now exists will never be the huge audience success in the UK that it has been in Sweden’, adding that ‘a work reaching sales of 36,000 copies in the UK would in a Swedish context make the work a sure best-seller’.

The MacDiarmid correspondence reveals a letter from Schubert dated March [1963] in which she expresses a feeling of being ‘out in the cauld blast’ and that they should both be girded ‘for the fray’. She asks MacDiarmid if there is ‘no fellow poet who can take up the cudgels’. Cannot he himself ‘write to the Times Literary, defending the original’?

![]()

The poem itself – this Harris Tweed, this simple, unpretentious and serviceable version of the poem – ends in the blackness of deep space, of space-night…:

‘…the Zodiac’s lonely night became our only home,

a gaping chasm in which no god could hear us […]

With unabated speed towards the Lyra

the goldonda droned for fifteen thousand years,

like a museum filled with bones and artefacts,

and dried herbs and roots, relics from Douris’ woods.

Entombed in our immense sarcophagus

we were borne on across the desolate waves

of space-night, so unlike the day we’d known,

unchallenged silence closing round our grave…’

(Cantos 102, 103)

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives & Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

In the construction of this blog post the following were used: (1) Clippings from the Radio Times, November 1962, contained in the MacDiarmid collections, Ms.2973-2974; (2) ‘Aniara på engelska’, av A. Alvarez, Dagens Nyheter, 6 Maj 1963, clipping in the MacDiarmid collections, Ms.2973-2974; (3) Hutchinson Group correspondence in the MacDiarmid collections, and correspondence with Elspeth Harley Schubert, Ms. 2094/5/2031-33, and Ms.2967; (4) Manuscript, some cantos of Aniara, in the MacDiarmid collections, Gen.894; and, (5) Aniara, A Review of Man in Time and Space, adapted from the Swedish by Hugh MacDiarmid and Elspeth Harley Schubert. Hutchinson: London, 1963.

If you have enjoyed this dip into the MacDiarmid material, have a look at earlier posts to the blog: I – Ms letter from Dylan Thomas; II – Ms letter from the Project Theatre, Glasgow; Recent acquisition – small archive relating to ‘The Jabberwock’; William Soutar’s caricatures of Hugh MacDiarmid, by Paul Barnaby; Hugh MacDiarmid and Mary Poppins: An unpublished letter in EU Archives, also by Paul Barnaby; and, Hugh MacDiarmid introduces Lewis Grassic Gibbon to publisher