DRAWING & SKETCHING, STUDYING & RESEARCHING, TRAVELLING & DREDGING, DESCRIBING MOLLUSCS & SHELLFISH, MUSEUM CURATION & PALAEONTOLOGY, PRESIDING OVER SCIENTIFIC BODIES & CLASSIFIYING TERTIARY FORMATIONS, AND LECTURING – ALL IN A SHORT BUT PACKED 39-YEARS… PROFESSOR EDWARD FORBES… ‘A BRILLIANT GENIUS’…

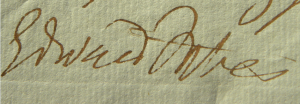

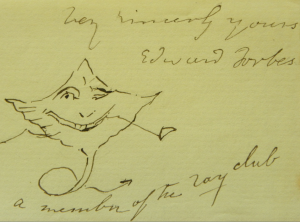

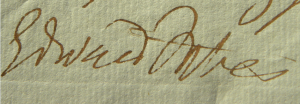

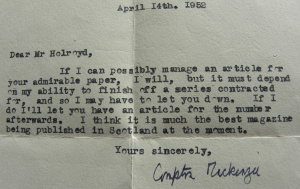

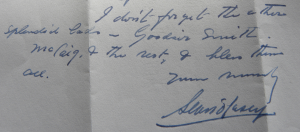

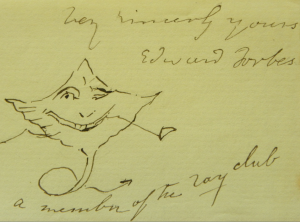

Signature of Forbes on letter, 11 March 1848. Dc.4.101 Forbes.

12 February 2015 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth in Douglas, Isle of Man, of Edward Forbes the marine biologist, geologist, naturalist and pioneer in the field of biogeography (the study of the geographic distribution of plants and animals). On the Isle of Man, Forbes is most noted for his cataloguing of the marine life inhabiting the island and the neighbouring sea.

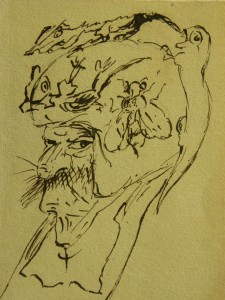

Born on 12 February 1815, Edward Forbes received his early education in Douglas and even in those early years he showed a taste for natural history, literature and drawing. His parents were said to have been so impressed with the artistic talent behind the drawings and caricatures on his schoolbooks that they sent him to London to study art with ambitions for a place in the Royal Academy Schools. His artistic talent was not good enough for the Royal Academy however, so in 1831 he entered Edinburgh University as a medical student instead.

Signature of Edward Forbes, from the Isle of Man, Edinburgh University session 1831-32. The signature was written in November 1831, and Forbes was the 115th student to matriculate. Volume ‘Matriculation 1829-1846’.

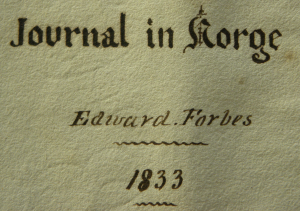

His 1832 vacation was spent looking at the natural history of the Isle of Man, and in 1833 he travelled to Norway, sailing on a brig from Ramsey on the Isle of Man to Arendal in Norway. He described his Norwegian trip in a journal – his Journal in Norge – illustrated with his own sketches. Barely four lines into his journal, started on Monday 27 May 1833, we find the first natural history log of the trip, ‘Caught some Gurnards … on one of them were several parasite insects’.

Title to the journal Edward Forbes wrote on his trip to Norway, 1833. From the ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

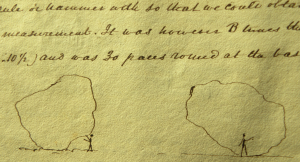

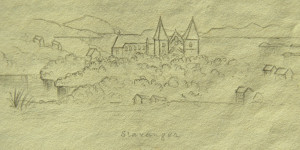

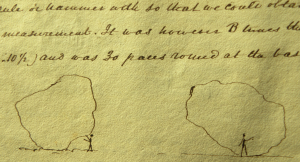

On Saturday 22 June 1833, Forbes was in the country around Stavanger, ‘hilly but apparently fertile’ where the rock was chiefly gneiss and mica slate. There he found an immense boulder though with ‘neither rule or hammer’ he ‘could obtain neither specimen or correct measurement’. From the ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

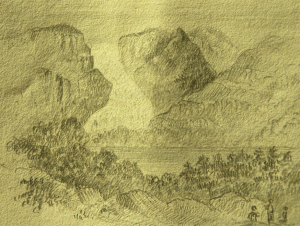

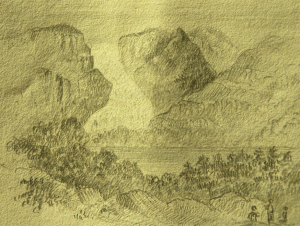

On Tuesday 3 July 1833, in the evening, Forbes arrived at a little village in the vicinity of the Glacier at Bondhus on Hardanger Fjord. He sat down at ‘a table plentifully supplied with the staple food of the country’. From the ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

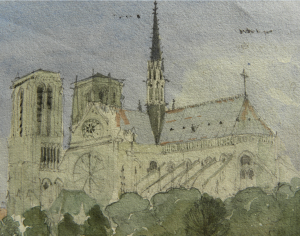

Other natural history during these years included dredging work in the Irish Sea, and travels in France, Switzerland and Germany. Indeed he spent the winter of 1836-37 in Paris studying at the Le Jardin des Plantes which included attending the lectures of De Blainville (1777-1850) and Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1772-1844), and looking at the geographical distribution of animals. He then travelled to the south of France and across the Mediterranean to Algeria collecting specimens. A born naturalist rather than a student of medicine, he had earlier – by 1836 – abandoned the notion of a medical degree and instead devoted his studies to science and literature.

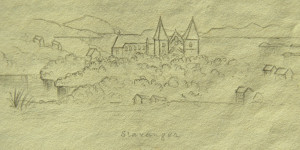

Sketch by Forbes of Stavanger, Norway, including Stavanger Cathedral (Stavanger domkirke) in his ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

Sketch by Forbes of Kronborg Castle (Hamlet’s Castle) at Helsingør, Denmark, in his ‘Journal in Norge’. Dc.6.91

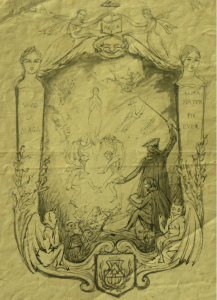

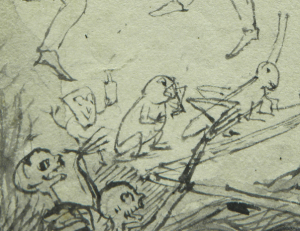

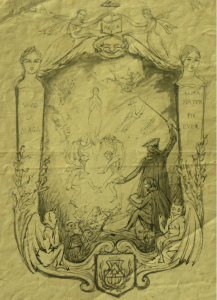

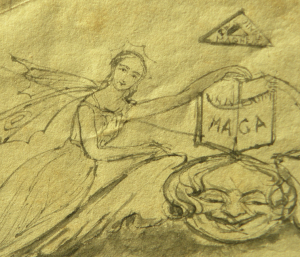

While at Edinburgh University, Forbes and John Percy were joint publishers of a magazine, called the University Maga, which was published weekly during session 1837-1838. Its frontispiece was sketched by Forbes and contained subjects within it which were similar to those commented on by Sir Archibald Geikie much later on in 1915. Forbes’s animals and figures are ‘in all kinds of comical positions and employments’, said Geikie (quoted from Manx Quarterly, p.329. Vol.V. No.20, 1919).

Detail from the cover of the ‘University Maga’ (pen and ink drawing) is shown here. Dc.4.101 Forbes.

Investigations by Forbes into the natural history of the Isle of Man occupied much of his time, leading to a volume on Manx Mollusca once he was back in Edinburgh. The remainder of the 1830s saw him touring Austria, delivering scientific papers and lecturing in Newcastle, Cupar and St. Andrews and to the Edinburgh Philosophical Association, on subjects such as terrestrial pulmonifera in Europe, the distribution of pulmonary mollusca in the British Isles, and British marine life. In 1839 he obtained a grant for dredging research in the seas around the British Isles, and towards the end of that year he published a paper on British mollusca in which he established a division of the coast into four zones.

The 1840s opened for Forbes with a series of lectures in Liverpool. He also visited London where he met other scientists, and he travelled and did more dredging. In 1841 he published a History of British Starfishes based on his own observations – and many observed for the first time – and that year too he was appointed as naturalist on board HMS Beacon engaged in surveying work in the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea. He also explored upland Turkey, looking at its antiquities, freshwater mollusca, plants and geology.

Small pen and ink sketch of a ray and reference to membership of the ‘ray club’ on a letter, showing the signature of Edward Forbes. The ‘ray club’ may refer to the Ray Society, a scientific text publication society founded in 1844. It was named after John Ray, the 17th-century naturalist. Gen.524.3.

Back in Britain again, Forbes took a post as Curator of the museum of the Geological Society, and in 1844 he became Palaeontologist to the Society. He presented a report on his research in the Aegean to the British Association and lectured before the Royal Institution on his studies of the littoral zones and his discoveries in these. Also in 1844 he became a Fellow of the Geological Society and Palaeontologist to the Geological Survey, and in 1845 a Fellow of the Royal Society. He was also voted as a member of the Athenaeum Club. Dredging in Shetland and around the west of Scotland occurred during this period, as did the presentation of a course of lectures at the London Institution and then also at King’s College.

Forbes was instrumental in the founding of the Palaeontological Society in 1847, and in 1849 he was working on the position in geological time-scale of the Purbeck Group (the Purbeck Beds) famous for its fossils of reptiles and early mammals. More dredging occurred, this time in the Hebrides, and more lecturing, and preparation for the on-going co-publication of a History of British Mollusca which appeared 1848-1852. His many dredging excursions contributed to this work. Between 1849 and 1850 he was busy arranging a new geological museum at the Geological Survey premises in Jermyn Street, London, which would open in 1851. Before that though, more dredging occurred in the western Hebrides, and more lecturing in the Royal Institution.

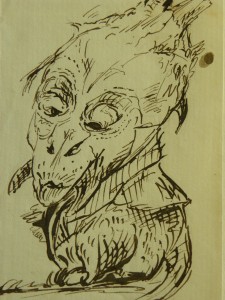

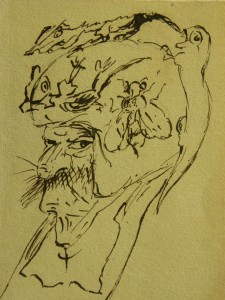

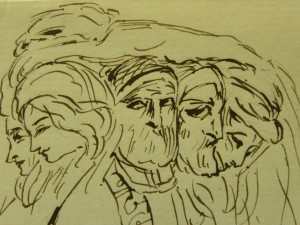

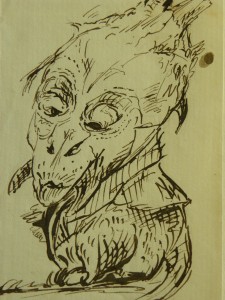

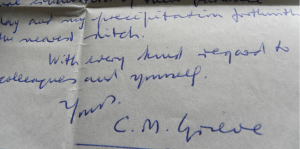

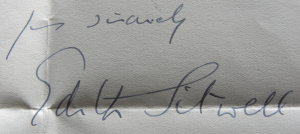

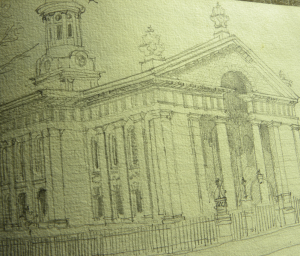

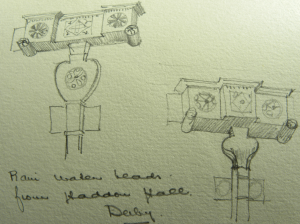

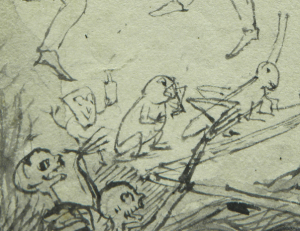

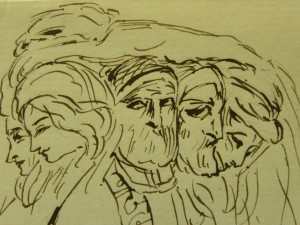

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.

In the summer of 1851, Forbes became Lecturer in Natural History in a new School of Mines (the Government School of Mines and Science Applied to the Arts, later the Royal School of Mines) which had been formed out of the efforts of geologist Sir Henry De La Beche (1796-1855). Indeed the staff of the Geological Survey became the Lecturers and Professors of the School of Mines, and the new School was located in the same Jermyn Street premises as the museum.

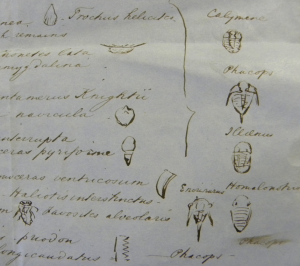

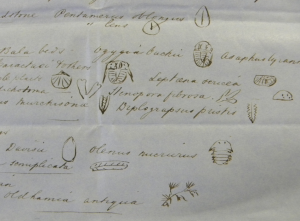

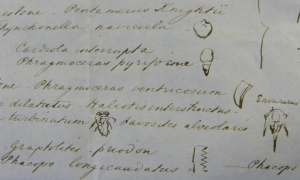

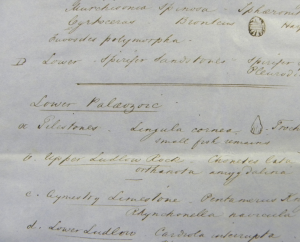

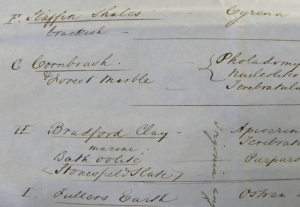

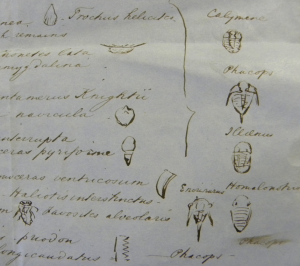

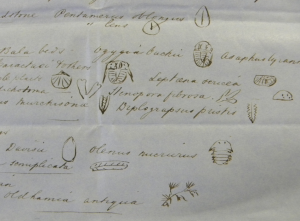

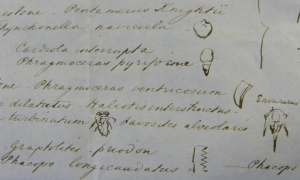

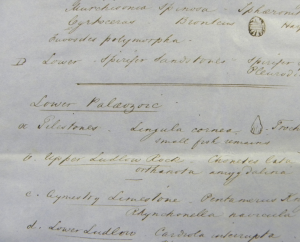

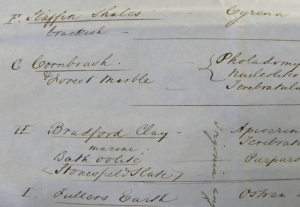

Tabular lists by Forbes. Gen.524.3.

Tabular lists by Forbes. Gen.524.3.

The winter of 1852-1853 saw Forbes working on the classification of the tertiary formations, and still a comparatively young man – in his late-30s – he was elected as President of the Geological Society in 1853. The following year, in 1854, he became Professor of Natural History at Edinburgh University, succeeding Professor Robert Jameson who held the Chair for nearly half a century from 1804 until 1854. In his History of the University of Edinburgh 1883-1933, Arthur Logan Turner would write that Forbes was among ‘a remarkable group of outstanding men’ whose ‘individual influence’ after the mid-19th century would help science become ‘seriously recognised in the University’ – the other remarkables included Lyon Playfair (Chair of Chemistry), P. G. Tait (Chair of Natural Philosophy), and Archibald Geikie (Chair of Geology). Another historian – Sir Alexander Grant – would describe Forbes as ‘a brilliant genius’.

Tabular lists by Forbes. Gen.524.3.

Tabular lists by Forbes. Gen.524.3.

Professor Edward Forbes delivered his inaugural lecture on 15 May 1854 but during the meetings of the Geological section of the British Association held in Liverpool he suffered from a fever. Forbes would not live to see publication of his work on the tertiary formations, and after only a few month’s tenure as Professor – after only a few days into the winter session 1854-1855 – he had to cancel his lectures owing to ill-health. He died shortly afterwards on 18 November 1854 at the age of 39. The brilliant genius ‘was extinguished’, his light ‘having just shown itself above the horizon’, Sir Alexander Grant was to write later.

Professor Edward Forbes was buried in Edinburgh’s Dean Cemetery.

Tabular lists by Forbes. Gen.524.3.

A student of Edward Forbes, James Hector (1834-1907), later Sir James Hector the Scottish geologist, naturalist, and surgeon, would name a mountain after his former Professor. Hector had participated in the Canadian Palliser Expedition to explore new railway routes for the Canadian Pacific Railway, and named the 8th highest peak in the Canadian Rockie Mountains after Forbes. Mount Forbes (3,612 metres) is in Alberta, 18 km southwest of the Saskatchewan River crossing in Banff National Park.

Organised by the Department of Environment, Food and Agriculture in partnership with Manx National Heritage, the Isle of Man Natural History and Antiquarian Society and the Society for the Preservation of the Manx Countryside, the Edward Forbes Bicentenary Marine Science and Conservation Conference will take place 12-14 February 2015 at the Manx Museum, Douglas, Isle of Man. The Museum will also stage pop-up displays on the life and legacy of Edward Forbes during the Conference.

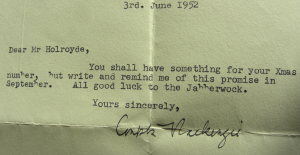

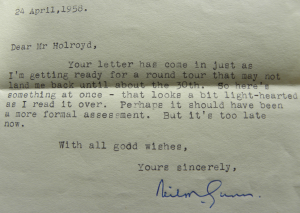

Signature of Forbes on letter, 15 June 1851. Dc.4.101 Forbes.

Dr. Graeme D. Eddie, Assistant Librarian Archives and Manuscripts, Centre for Research Collections

Sources:

- Manx Worthies. Professor Edward Forbes (from the Manx Note Book, by A. W. Moore): Edward Forbes [accessed 2 Feb 2015]

- Eric L. Mills. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Forbes, Edward (1815-1854), marine biologist, geologist, natural historian [accessed 2 Feb 2015]

- Grant, Sir Alexander. Story of the University of Edinburgh during its first three hundred years in 2 volumes. London: Longmans Green and Co., 1884. Vol.II., p.434-435.

- Turner, A. Logan. History of the University of Edinburgh 1883-1933. Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1933. p.240.

- Material contained within Coll-133, Papers of Edward Forbes, Edinburgh University Library (Centre for Research Collections)

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.

Throughout their work, ‘Memoir of Edward Forbes, F.R.S.’, Macmillan & Co., Cambridge and London, 1861, Archibald Geikie and George Wilson include vignettes and tail-pieces by Edward Forbes at chapter-ends… Probably not unlike these here. Gen.524.3.