Zexuan is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University, and recently completed a six-month placement with the musical instrument collection of the University of Edinburgh. In this post, Zexuan shares the highlights of his work, which focused on the study and preservation of historic bagpipes.

My project centred around the historic bagpipes held within the University’s Heritage Collections and I employed modern techniques to measure, model, and compare these instruments in a controlled virtual environment. Below, I’ll walk you through the key processes and achievements from my time working with these fascinating artefacts.

Modelling Historic Bagpipes

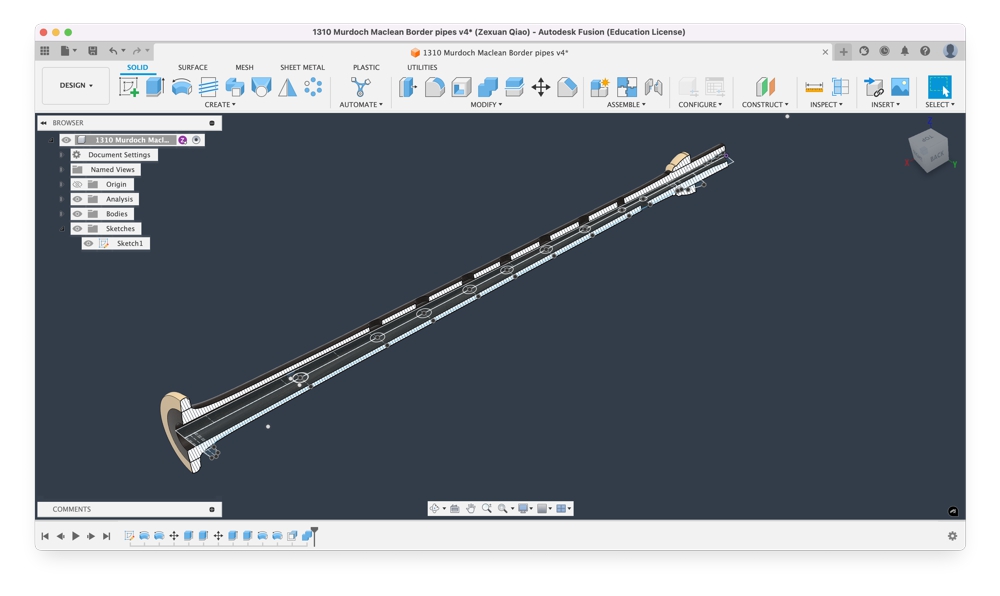

One of the core tasks of my project involved creating digital models of the instruments. Using CAD (Computer-Aided Design) software, I produced 40 models of bagpipes from the collection. These digital models are not just for viewing; they are designed to be manufactured using technologies such as CNC machining and 3D printing.

A rendered image of a 3D model of the drones of a set of union pipes made by James Reid in England circa 1840, MIMEd 1352

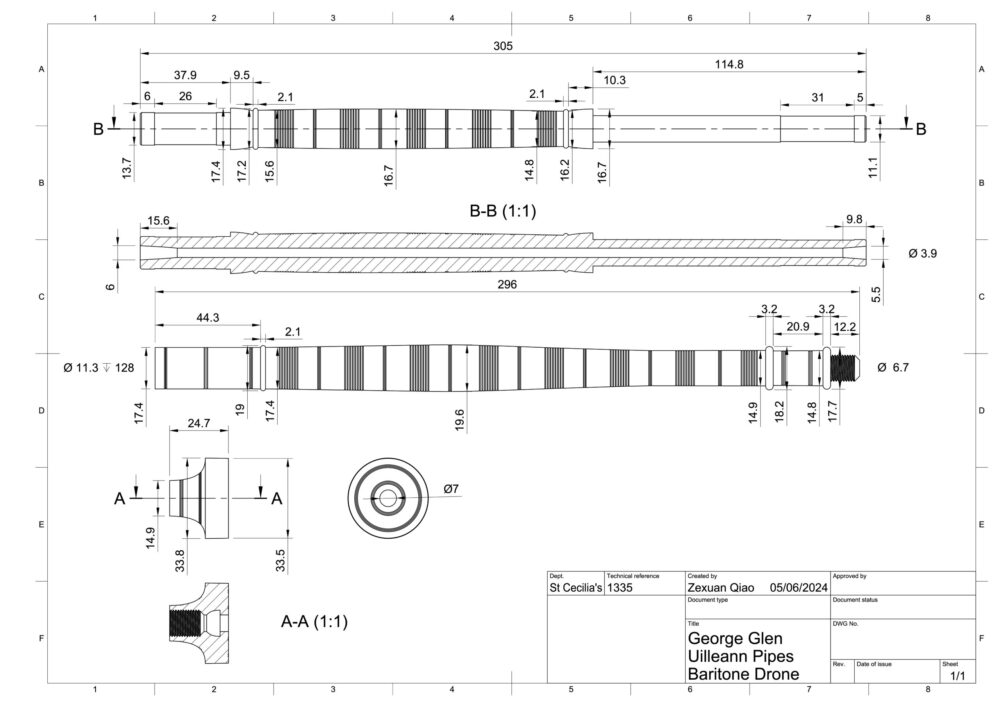

Additionally, I’ve been converting these 3D models into 2D technical drawings, which will allow instrument makers and researchers to use them for further study or reconstruction work.

A technical drawing for the Baritone Drone for a set of Uilleann pipes made by George Glen, MIMEd 1335.

The Glen Family and the Collection

The Glen family established their first shop on the Cowgate (only a few blocks from St Cecilia’s Hall!) in 1827 and served the Scottish piping community until 1980. Thomas Glen was not only a skilled bagpipe maker but also a prominent musical instrument dealer in Edinburgh during the time. J&R Glen amassed a collection of historically significant instruments, some of which were loaned to exhibitions in the late 19th century. Glen-made bagpipes are highly sought after for their exceptional quality, renowned for their mellow and homogenous sound, and are considered as some of the finest examples of Great Highland Bagpipes.

A common stock stamped “DAVID GLEN / EDINBURGH”, dated between 1873-1916, MIMEd 1357

A significant portion of the bagpipes in the collection comes from the Glen family. In the early 1980s, Andrew Ross loaned the remaining stock and instruments from the Glen family shop to the museum. This loan laid the foundation for what has become one of the most comprehensive collections of historic bagpipes. In 2016, the Andreas Hartmann-Virnich Collection was added to the museum, bringing with it several full sets of Glen instruments in good condition.

One of the challenges with historical collections is managing database records. During my placement, I updated database entries for a wide range of instruments, with new information and corrections including details about the makers’ working periods, helping to distinguish between the different generations of the Glen family.

Beyond the Glen family, I worked on 274 additional entries, focusing on instrument makers from Scotland, England, and France. This work involved ensuring that the details for each maker were as accurate as possible on the database.

A box of Highland, Lowland, Pastoral and Union pipes chanters made between 1800 and 1900 from various makers.

One of the standout discoveries was a second-reel-sized chanter made by Murdoch MacLean, one of Glasgow’s earliest professional bagpipe makers. Here’s a 3D model rendering of this remarkable instrument:

3D model of a bagpipe chanter made by Murdoch MacLean in Glasgow circa 1810, MIMEd 1310 (the CAD software chosen for modelling this was Fusion 360)

Another aspect of my project involved identifying the materials used in these historic instruments. Advances in material studies have allowed us to determine the sources of materials with much greater accuracy than when the original checklist was compiled in the 1980s. For example, we now have a clearer understanding of where the woods and metals came from, giving us new insights into the construction of these instruments.

In addition, I’ve updated the names of some of the instruments in the collection, using terms that are more widely accepted today, such as “pastoral pipes” and “union pipes.” I also paid close attention to the maker’s stamps found on these instruments, which are crucial for dating and identifying their origin.

A great Highland bagpipes chanter by Peter Henderson, made from African Blackwood and elephant ivory, MIMEd 1390

Looking Ahead

So, what’s next? I’ll be completing the remaining drawings and models of the instruments and updating the information in the collection’s management system so that this work can benefit future researchers and makers.

It’s been a deeply rewarding experience to contribute to the preservation and understanding of these historic instruments, and I look forward to seeing how these digital models and technical drawings will be used in the future.

Thank you for reading, and I hope you have learned a bit more about the bagpipes in the University collections here!

Very interesting indeed. Congratulations for your research!

Great work Zexuan. I don’t know if you are avare, or EUCHMI, that I would like my currrent collection of early Scottish bagpipes, about ten times greater than the part that EUCHMI acquired in 2012-1013 to sell/loan/donate to the same place. It would thus become the largest public collection of its kind worldwide. This would happen in a couple of years from now. I still have to study and catalogue my sets which, as you know, are all playable with very few exceptions. The kind of work you do would be great. There are some essential asses like the two only surviving (and playable) Pastoral pipes by Donald MacDonald and about 40 pre-Victorian pipes in all. I would like to start discussing this matter in a foreseeable future. Best regards, Andreas Hartmann-Virnich

Dear Dr Hartmann-Virnich

Many thanks for your message. I would be very happy to discuss your Collection and the possibility of it finding a home in Edinburgh in due course. Please do contact me on Jenny.Nex@ed.ac.uk.

All best wishes

Jenny

Dr Jenny Nex

Curator, Musical Instrument Collection, University of Edinburgh

Assets, not “asses.” There are a complete range of pipes and chanters and à walking stick bagpipe by the four generations of the MacDougall family, about ten early Border pipes, several essential early makers like Hugh Robertson, Donald MacDonald, Allan MacDougall and Malcolm MacGregor and also unique or unrecorded makers. And many unattributed early sets fom 1750 onwards that have never been on public display…

Dear Andreas,

Many thanks for your valuable contribution and expertise. Now that I have completed this placement, I am back in Belfast. I truly appreciate all you have done and will be in touch soon, as I have just returned from the William Kennedy Festival.

Kind regards,

Zexuan

Hi Zexuan, I have just pirchased a very interesting early Border pipe, from the former Glen-Ross collection, possibly by Donald MacDonald. Contact me by email for pictures and a more in-depth discussion. Best regards Andreas

Fascinating and important work. Describing the past is interesting, but all the more so when you’ve opened a clear way forward – physical 3D models of historic instruments will give us far better understanding of them than an abstract verbal or 2D visual description. And they would be playable!