In the first post of this two part series, our Musical Instrument Care Technician (and former conservation intern), Esteban Mariño Garza, discusses his Musical Instrument Research and Documentation Internship project to try and discover who made one of the harpsichords in the Musical Instrument Collections of the University.

My name is Esteban Mariño, I am PhD candidate at the Royal College of Music for the Music and Material Culture Program. Last year (2023) I had the opportunity to work in an internship with the Musical Instrument Collections of the University of Edinburgh at the Saint Cecilia’s Hall under the supervision of Senior Conservator, Jonathan Santa Maria Bouquet. My project consisted in documenting and researching a double manual harpsichord by Jerome Mahieu (MIMEd 4477). The internship is part of an ongoing project entitled ‘Eighteenth-century Flemish Harpsichords under the Spotlights’ and directed by Pascale Vandervellen, curator of keyboard instruments at the Musical Instrument Museum in Brussels.

Conservation, documentation, and research are quintessential activities of organology. The complexity of musical instruments conservation lies in the paradox between musical function and the preservation of historical information and how the fulfillment of either means the loss of the other. Musical instruments besides enabling music, have a range of aesthetic, historic, scientific, social, and spiritual values since they provide social meaning to people’s lives. The public as well as musical instrument specialists, quoting the words of conservator John Watson have ‘a claim to use but an obligation to preserve.’ Documenting and researching are excellent methods for preserving historical evidence and thus, for guarding its cultural significance.

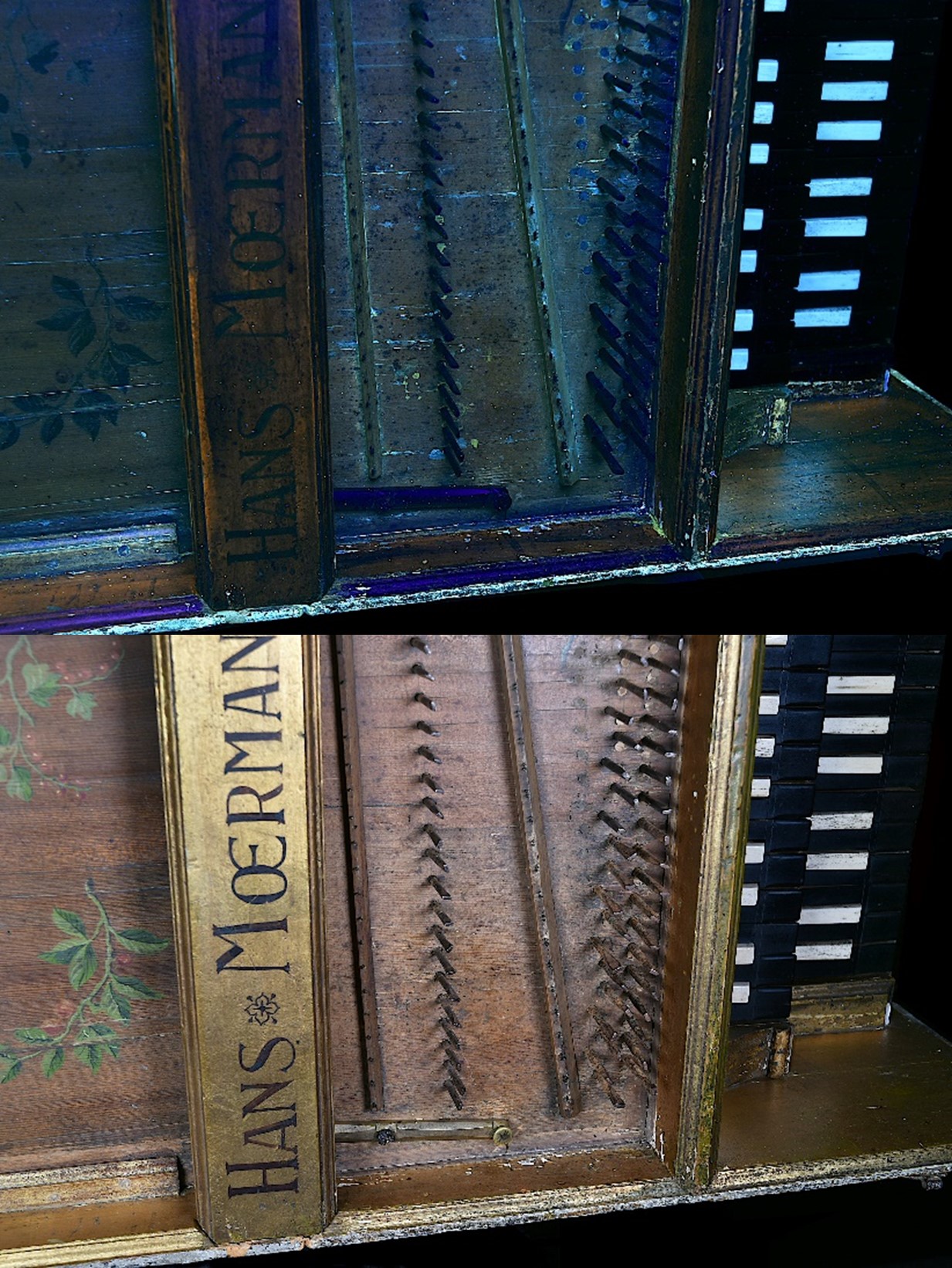

Even before I started the documentation of the MIMEd 4477 harpsichord, I knew it had an impressive and puzzling history. Signed on the jack rail as ‘Hans Moermans me fecit Antwerpiae 1642’ and later attributed to Jerome Mahieu, an active maker of Brussels before 1737, this harpsichord’s attribution revealed to be one of the most important questions still to be answered. To bring the pieces of the puzzle together, I first focused on a full scientific material investigation of its construction and past alterations. I started by revising the existing documentation of the instrument and identifying key sections of the instrument to be analysed. Then, I measured in detail each section of the instrument, a task that proved to be equally challenging as rewarding.

Double Manual Harpsichord by Jerome Mahieu (MIMEd 4477).

The whole point of a documentation project is to record in detail every part of the instrument by written, photographic, and graphic/digital methods in order to better understand the object.

The photographic documentation was very important, as well as inspecting it under ultraviolet light, which allows for the identification of materials that otherwise appear invisible. A major process, still under development is a full 3D scanning. This kind of documentation produces highly accurate information and valuable data which allow us to understand the object but also share the information with other researchers. Scanning a large and complex object, such as this historic harpsichord proved to be a quite challenge.

Double Manual Harpsichord by Jerome Mahieu (inv. nr. MIMEd 4477) under ultraviolet light showing the gilding in the case work and on the jack rail, which bears the inscription of Hans Moermans. At some point it was expected that the signature on the jack rail would fluoresce different than the rest of the gilding, based on the fact that the inscription is not original. Surprisingly, it seems that the jack rail was gilded with the same materials and techniques as the rest of the case. Perhaps the jack rail is original, and the signature was added later. Perhaps, Jerome Mahieu counterfeited this instrument since the moment he made it.

A painstaking process was the dendrochronology analysis of the wood, which is a scientific method that allows to date wood by measuring its growth-rings. We can gladly report that the latest date in which this harpsichord could have been built is 1648. Thanks to this study we can confirm, on a scientific basis, that the 1642 inscription is not original and was not made by Hans Moermans. More analysis followed when I look inside the case with an endoscope, revealing a series of alterations reinforcements and braces held together with modern iron nails intended to provide more structural strength to the harpsichord.

Close-up photographs with a stereo microscope for denchronological analysis.

Last but not least, we carried out an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy analysis to identify the decorative materials such as the gilding and the pigments on its richly ornamented soundboard.

XRF analysis of the pigments employed in the decoration on the soundboard.

Research and documentation are like making a movie, you shoot your scenes and then you ‘wrap-up’ the material to be later processed in the editing room. For sure, this was the initial phase of a really exciting project whose story is yet to be told once all the data is analysed and interpreted. There is still no single physical evidence, found in this harpsichord that can be linked with Jerome Mahieu as no signature has been found. The rose bares the initials ‘HM’, which could be Hieronimus Mahieu but then again, they could be an attempt to display a ‘Hans Moermans’ initials. Scholars consider that Jerome Mahieu, besides an important Brussels instrument builder and merchant, also made and sold counterfeit harpsichords.

Could the MIMEd 4477 be a fake? The mystery continues and we will do our best to solve it! Stay tuned for the second part of this blog!