In the first post of this two part series, our Collection Care Technician, Robyn Rogers, discusses her Decorated Paper rehousing project. If you want to learn about the uses, production, and trade of decorated paper, you can visit the online exhibition on this collection, curated by Elizabeth Quarmby Lawrence, here. Look out for the second post in this series soon, in which Robyn will discuss mounting loose leaf papers.

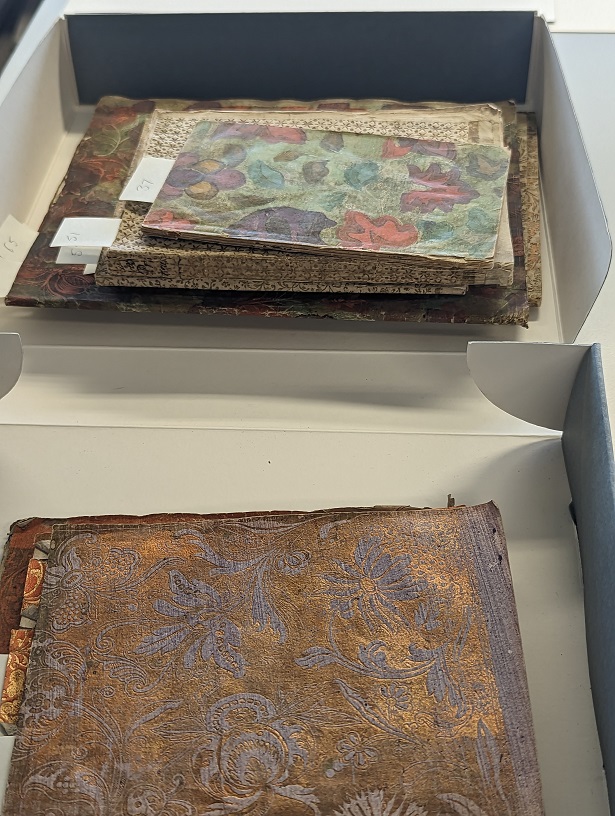

In my free moments at the Centre for Research Collections, when I am not assisting on wider projects, I have been working to rehouse the entirety of our newly acquired decorated paper collection. This collection is complex, varied, and contains many beautiful examples of historic decorated paper. In the hopes that this collection will become a valuable teaching and research resource for students and staff at the Edinburgh College of Art, I have been making bespoke rehousing solutions for each individual item in the collection. The collection is large and diverse, and includes hardback books, textile bindings, limp bindings with paper wrappers, long rolls of wallpaper and loose-leaf material. The papers themselves are a mixture of paste papers, brocade papers, block printed patterned paper and bronze-varnish paper.

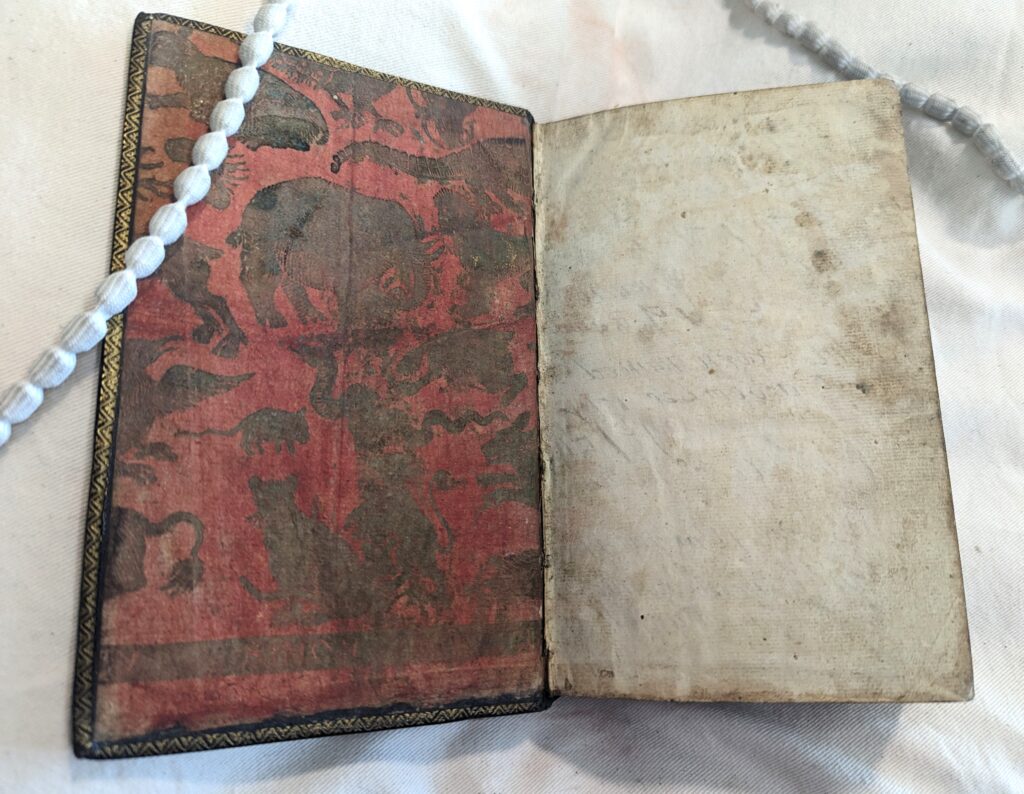

An example of a book with decorated paper end papers. This paper has been block printed.

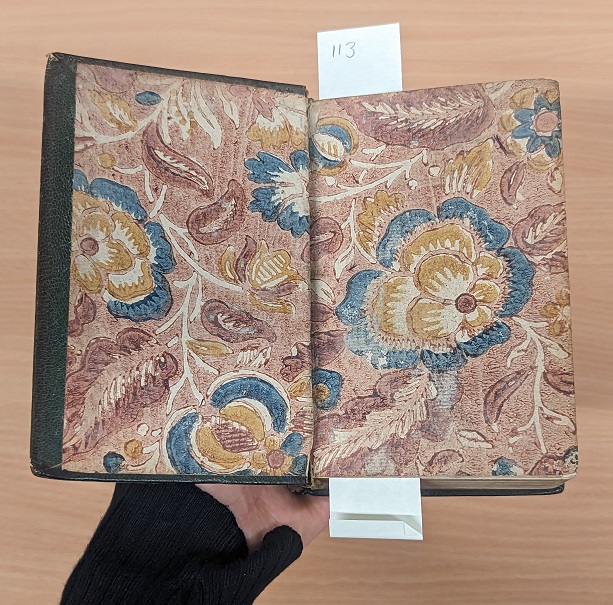

An example of a paper bound volume with a brocade paper wrapper. This volume also has its own decorated paper folder.

An example of rolled decorated wallpaper. This paper has been block printed.

Historically, decorated papers were used in a variety of ways, often as linings for cases and trunks, adorning pieces of furniture or even as the back of playing cards. However, in these instances the papers are unlikely to have survived. The vulnerabilities of paper mean that the few surviving examples are likely to have become bleached and damaged through frequent handling and years of light damage. In contrast, decorated papers used as book wrappers or as endpapers are more likely to have survived and have often retained their vivid colours. Books kept upright on a shelf are less exposed to light, while endpapers are rarely exposed and are physically protected by the structure of a book itself. Consequently, books containing decorated papers have become an invaluable resource for the study of historic paper design and production.

This collection has been particularly rewarding to work with as it demonstrates the importance of preserving books and library materials as important examples of material culture. When working in a library environment, it is often presumed that the printed words in a book, and therefore the text block, is the most important thing to preserve. Indeed, many of our rare books are digitised, so that researchers across the globe can access the information in each text. Keeping the pages and text block in good condition is essential for this work. However, much of the information that is contained within a historic book can be found outside of the pages. This collection demonstrates this especially well, as each example of decorated paper can give an insight into paper manufacture, trade, and use. The focus of care shifts from the text block to the covers, paper wrapper, or endpaper.

This end paper has been well protected by the hardcover of the book.

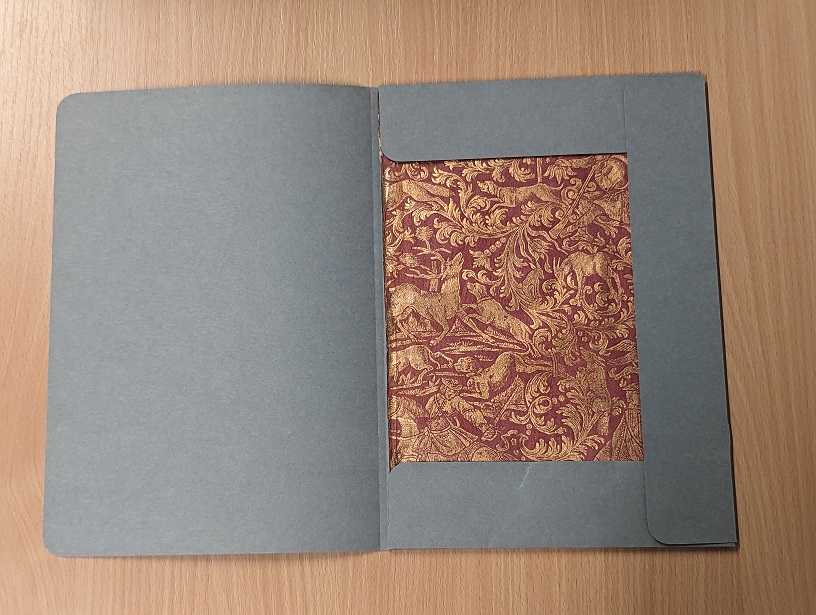

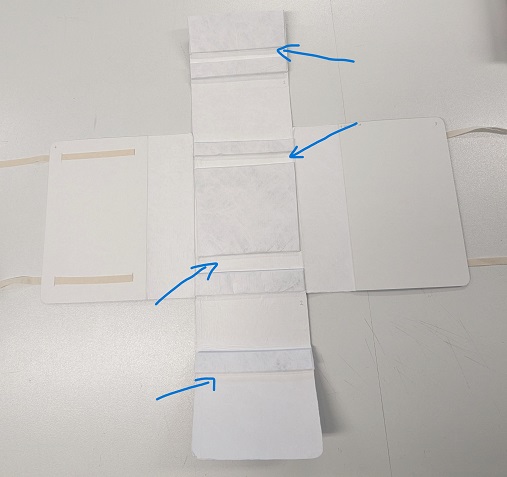

When rehousing such a large and diverse range of material it is sometimes hard to know where to start. I focused my work by dividing the collection into three main categories – paper bindings with decorated paper wrappers, books with decorated endpapers, and loose-leaf material. I then established which group would be the most vulnerable. I decided that the bindings in decorated paper wrappers were at greatest risk of damage through handling and light exposure, so set about making enclosures for these. After consulting our Rare Books and Literary Collections Curator, I envisioned that these paperbound volumes would be viewed in large groups for study through comparison. It became apparent that each binding needed a bespoke enclosure, and ideally one that revealed a large extent of the decorated paper wrapper, while minimising direct handling. For limp paperbound volumes I would usually make traditional four-flap enclosures or phase boxes, however this would obscure most of the decorated paper. To prevent this, I designed folders with three small flaps and one larger cover. This design allows a viewer to see a large area of the decorated paper without directly handling the volume. I made one hundred and twelve of these custom enclosures, using 230gsm archival paper – switching to 350gsm for larger, floppier volumes. Once completed, I grouped these by size into archive boxes. It’s now much easier to access these volumes, and view many of the paper wrappers together.

This is just one of the many custom enclosures I made. The window allows a viewer to see a large extent of the decorated paper without taking the volume out of the enclosure.

The paper bindings as they were stored before rehousing.

Once in enclosures, I housed the volumes in archive boxes in size order.

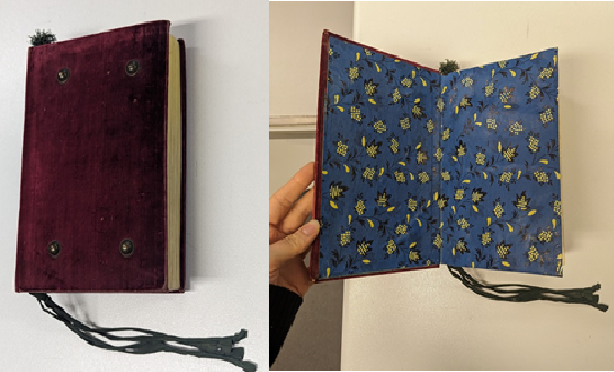

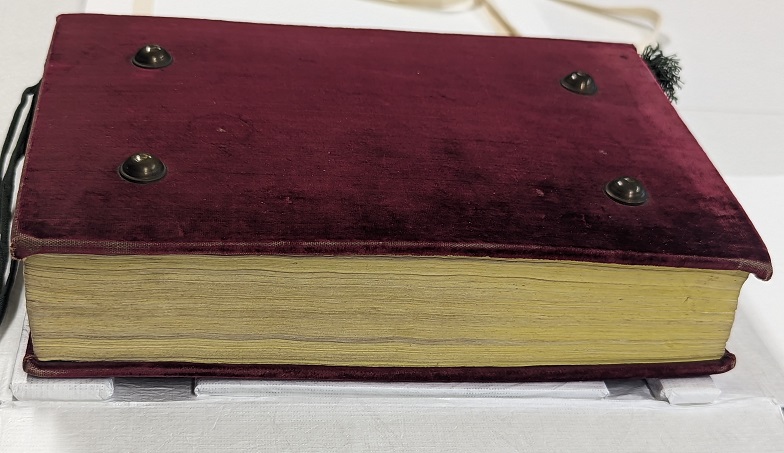

Next, I tackled the books with decorated endpapers. I cleaned the head and foredge of each book with a museum vac and used soft brushes and a smoke sponge to clean the pages of a few particularly dirty volumes. I avoided using a smoke sponge on any decorated papers, so as not to damage the design, but frequently cleaned the adjacent pages, to prevent the accumulation of dust that could become bonded to the paper. Most of the volumes are in good condition with few structural vulnerabilities, so I decided that these could remain stored upright on shelves without enclosures. I made exceptions for volumes with weak bindings, as well as textile covered volumes and volumes with external metal decoration and fastenings. For textile bindings, I made custom phase boxes, and lined the inside with Tyvek using EVA adhesive. For bindings with metal fastenings and decoration I made Plastazote inserts which I covered with Tyvek to create recesses for each feature to sit in comfortably. This also protects any adjacent books on a shelf, as it limits surface abrasion or warping that could be caused by protruding metal parts.

I made a padded phase box for this presentation binding with a textile cover, metal adornments and decorated end pages.

The inside of this bespoke padded phase box. The Tyvek covered Plastazote creates a recess for the metal adornments to rest comfortably.

The presentation binding sitting happily in its new enclosure.

I have yet to tackle the loose-leaf material in this collection, however I hope to create bespoke window mounts with T-bar hinges. Look out for the next post in this series to see how I get on …

Pingback: Giving Decorated Paper a Home … Loose-leaf Material | Preservation Perspectives