In this week’s blog, Sarah MacLean, an MA Conservation of Fine Art student from Northumbria University, describes a two-week work placement she undertook with us in July 2018…

During my time studying Fine Art at Undergraduate level, I always did big things; used metre upon metre of canvas, and sculpted near-immovable forms twice my height. Now, as an MA Conservation of Fine Art student at Northumbria University, large format works are still where my interests lie, and I’ve had the opportunity during my work placement at the CRC to work on a wide variety of those.

The works I’ve been able to conserve so far during my time here are part of the Patrick Geddes Collection. Geddes (1854-1932) was a Scottish-born polymath with interests and expertise in biology, sociology, geography, and urban planning, and it’s for his pioneering work in this latter field that he is best known. As such, the large format plans on which I’ve worked within the Collection so far are mainly hand-drawn and coloured mappings of urban developments in locations everywhere from Dunfermline to Imperial Delhi.

A pleasant and unexpected feature of hand-drawn and coloured works of art on paper – timorous marginalia beasties!

The conservation issues presented by these large format works have been fairly consistent across the board, and have mainly necessitated the same kinds of intervention.

Works of such size, for example, and particularly those that have served as functional objects typically accumulate significant surface dirt, the majority of which I was able to remove from each object with smoke sponge (a soft dry cleaning sponge made from either vulcanised natural rubber or a synthetic, latex free equivalent). Most of the works were completed on fairly thick wove paper and backed with linen so thorough and careful cleaning could be undertaken by this method, especially on the verso.

The one exception was an early 20th century panoramic photograph of Sydney, Australia which was backed with rough sugar paper. In this case, the paper was easily cleaned with smoke sponge but the delicate state of the silver gelatine photograph itself required careful cleaning using cotton swabs and a 1:1 solution of water and IMS (Industrial Methylated Spirits) to remove surface dirt.

The contrast between an area of linen backing that was surface cleaned with smoke sponge (left) and an uncleaned area (right).

Some of the other main issues presented by large format paper objects are structural ones. Even outside of their functionality and the attendant increase in handling, limitations on the ease of storage and transit often mean that large format objects are rolled or even folded. As such, the likelihood of new tears forming and old ones worsening is increased, as is the presence of planar distortions.

It was not possible in this instance to humidify or press to remove any such planar distortions but a wide variety of tears and losses present within each object were easily repaired. The thickness of the paper itself coupled with the linen backings led me to choose a fairly heavy Japanese repair paper and a thick, un-diluted wheat starch paste – each object at this stage was to be rolled and re-housed so although aesthetics were not discounted, I felt that the strength and durability of repair were the most important to ensure.

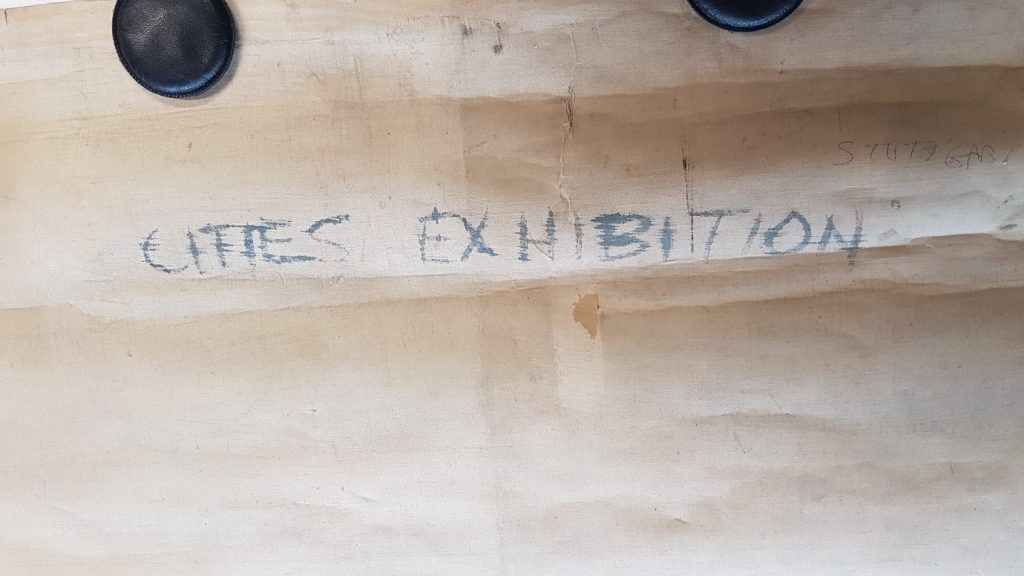

A tear at the top edge of the early 20th century map of Stuttgart prior to conservation (verso). Several fragments were completely detached and the linen backing heavily warped.

A great deal of the practical work I’ve undertaken thus far at Northumbria has been on pre-prepared samples so I have found numerous challenges in working on actual large format objects. I had not, for example, worked with any photographs before, nor any objects that had been backed with linen. This latter challenge was particularly difficult on one of the last objects on which I worked – an early 20th century map of Stuttgart, Germany.

The map had been backed with linen and the paper itself had been varnished. This added rigidity and, coupled with the rolling of the map resulted in some fairly dramatic tearing, cupping, and cockling to the paper surface. A large tear at the top edge of the object was made particularly challenging by the linen. An historic repair had been attempted but was unsuccessful and resulted in stretching of the linen backing. The subsequent distortion of the linen made the attached paper fragments very difficult to properly realign, and made the pressing of these realignments a challenge also.

A tear at the top edge of the early 20th century map of Stuttgart after conservation (recto). The stretching and distortion of the linen backing made the realignment of the paper fragments very difficult.

My work at the CRC has allowed me to improve my practical skills massively – no amount of research and reading, nor however many hours spent painstakingly perfecting a technique on a sample, can compare to real conservation work on real objects. And another, equally important, change that’s resulted from my work here has been an overall increase in the level of confidence I’ve felt in my time-management and decision-making as well as in the accuracy and efficacy of my practical work.

Going forward, the work I’ve completed here at the CRC will also contribute towards the research for my final year thesis. Having hands-on experience of handling and conserving large format works, and having been able to learn more about their storage and display will now allow me to focus my research further and effectively survey a number of other institutions regarding the ways in which they handle, store, conserve, and display the large format works in their care. The aim of this research will ultimately be to investigate and determine how the treatment of large format works of the past could improve the ways in which we handle, store, conserve, and display increasingly complex and ephemeral contemporary works in the future.

I HAVE A OLD PARCHMENT GRAVE PAPER WHICH IS MY GREAT GRANDFTHER S . CAN YOU ADVISE ME ANYWAY OF CLEANING IT AS IT IS RATHER DIRTY AND I SUSPECT MOULDY. THE DATE IS 1882. IF IT IS NOT SUITABLE FOR ME TO DO THIS MYSELF COULD YOU LET ME KNOW THE COST OF A PROFESSIONAL. SINCERE THANKS

Hi Maureen,

Many thanks for your comment. If you suspect the paper mouldy, I would recommend taking it to a professional conservator, rather than trying anything yourself, as this could lead to further damage. If you are based in the UK, you can find an accredited conservator near you by searching on the Conservation Register. http://www.conservationregister.com/

Unfortunately, it is hard to assess the cost without seeing the item itself, it would depend on the size and level of surface dirt and mould, so again I would recommend getting in contact with a conservator who should be able to give you some more advice and a free quote.

Best wishes,

Emily