As part of my ongoing conservation treatment plan, I have been asked to address the needs of the Special Collections popular and regularly consulted pamphlet series. We are all used to seeing, and using, pamphlets as part of our everyday lives, whether they are marketing the latest products, persuading us how to vote (you may see a lot more of these pamphlets in the coming months!), or why we should be eating healthier. However, the use of pamphlets is by no means new, and has been around for centuries, becoming widely used with the invention of the printing press. Then, as now, they were an effective, low cost and simple means by which to distribute information to a large audience, often being used for propaganda purposes, whether religious or political.

But what exactly is a pamphlet? Thankfully, following their 1964 General Conference, UNESCO provided us all with a handy classification. A pamphlet can be defined as “a non periodical printed publication of at least 5 pages but not more than 48 pages, exclusive of the cover pages, published in a particular country and made available to the public”. Anything with more than 48 pages would be classed a book. And with that cleared up…

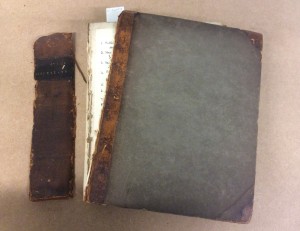

Pamphlets, when they are first produced, will usually be held loosely together along the inner margin. However, many of the pamphlets in the collection have, at some point in the past, been bound together to create larger volumes. Although this does have benefits, allowing them to be more easily shelved, accessed and consulted, there are now a number of associated conservation issues with these volumes. These have ranged from surface dirt through to detached or loose cover boards and/or detached or partially detached spines.

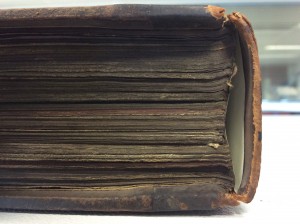

Prior to undertaking any interventive conservation treatment, the volumes were surface cleaned. Many of the pamphlets which have been bound together are different sizes, resulting in irregular edges to the textblock. This has allowed surface dirt to collect between the pages and page edges, as the image amply demonstrates. Firstly, the volumes are lightly cleaned with a soft brush along the textblock edges to remove any loose dirt, before a smoke sponge (made using vulcanised natural rubber) is used to reduce the surface dirt affecting the pages.

If the volume’s boards have become detached, or are loose, I am, in most cases, able to reattach the board, or reinforce the inner join, with the use of Japanese tissue (a thin, strong paper which comes in varying thicknesses depending on the repair required) and wheat starch paste.

The reattachment of the spine is slightly more involved, as it requires accurately measuring and fitting a new spine hollow – these create a gap or ’hollow’ between the spine and the textblock, reducing pressure on the binding. Using acid-free paper and paste (a combination of wheat starch paste and a stronger Evacon adhesive), the new hollow is first adhered to the textblock upon which the spine piece can then be positioned and pasted in place. Although, judging by the picture, it appears that a horrible accident has befallen the poor object; bandages can be used to ensure that there remains good contact between the new spine hollow and the textblock/spine piece whilst drying.

So next time you see a discarded and unlooked at pamphlet, give a thought to their long history and importance in spreading the word, allowing people a platform to express their thoughts and beliefs in the pre-television and internet era.

Post by Emma Davey, Conservation Officer