Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

February 25, 2026

The History of Vivisection

Posted on October 19, 2024 | in Uncategorized | by lbeattieToday we are publishing an article by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement team, on the history of vivisection.

This is the first of two blogs featuring items from the One Health Project (2021 – 2024) held in the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections. In this article we shall explore the history of vivisection both from the perspective of those opposing or seeking reforms in the practice, and from its proponents advocating why it is essential for advancement of medical science, not least in the fields of veterinary medicine itself.

Whilst there are no images of animal experiments in the blog, or any graphic descriptions of procedures, it is recognised that vivisection continues to be an emotive subject and that therefore some people may choose not to read any further.

The History of Vivisection and of its proponents and opposers

Animals have been used by humans in experiments dating back to the times of ancient Greece, with second century Roman physician Galen being referred to as the father of vivisection following his dissection of farmyard animals.[1] The term vivisection is used to describe the practise of experimenting upon living animals for medical research purposes, primarily with the aim of achieving advances in the understanding and treatment of human illness and disease, although it has also been widely used elsewhere, such as in the testing of cosmetic products prior to their approval for human use.

In the 17th century, Edmund O’Meara was an early and prominent critic stating that “the miserable torture of vivisection places the body in an unnatural state”, combining both the view that the practice is cruel and concomitantly unreliable as the pain and suffering inflicted could serve to skew the reliability of any scientific research findings being attempted.

In the UK. the Cruelty to Animals Act of 1876 became the first form of regulation designated with the task of regulation over the testing of animals, endorsed by the celebrated naturalist and biologist Charles Darwin, who commented: “You ask about my opinion on vivisection. I quite agree that it is justifiable for real investigations on physiology, but not for mere damnable and detestable curiosity. It is a subject which makes me sick with horror, so I will not say another word about it, else I shall not sleep tonight”.

Whilst both of the interjections above make observations about how vivisection is practised, for what purposes, and raise questions on its potential to precipitate useful applications in science and human medicine, they do not specifically constitute an outright opposition to any use of vivisection either on absolute ethical grounds, or those of scepticism that any findings from the practise can ever deliver truly useful medical knowledge, such as that which might be applied to the benefit of combating disease or illness in humans.

Prior to this act being passed the UK National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) was formed in London, founded by the humanitarian Frances Power Cobbe.[2] Initially her campaigning work in this area was focused to seek regulation on the practice of vivisection, such as the use of anaesthesia to make it more humane, but she later became disillusioned with this approach, splitting from NAVS to form the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection in 1898 (now known as Cruelty Free International), whose remit instead ultimately argued for the outright abolition of vivisection and use of all animal experiments.[3] Cobbe was also a prominent force in the movement for Women’s Suffrage.

The history of opposition to vivisection forms a spectrum, from an absolute stance that it is both unethical to experiment on animals in any circumstances, and that any medical research obtained from it cannot be relied upon to apply equally in the case of an entirely different species such as humans, to those advocating that it can be used but only where it does not cause undue suffering to animals and where it might precipitate meaningful advances, such as in the treatment of disease in both humans and other animals themselves.

The first item in the collection that I viewed is entitled Animal Experiments Newspaper Cuttings in Bound Volume 1956-1960.[4] This is chiefly focused around Scottish and UK newspaper articles from the viewpoint of critics or opponents to vivisection. The Scottish Society for the Prevention of Vivisection (SSPV, and now named as the organisation onekind.org) feature prominently in the selection of press cuttings.

In an excerpt from the Isle of Wight Times from 31/3/1955, there is a focus upon the SSPV influential publication entitled “This should not happen in Britain”, created in response to allegations that the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SSPCA) in Canada were providing stray animals to laboratories for use in research, and that this was unacceptable from such an organisation, even though at the time stray animals that could not be secured a home would routinely be destroyed, so in itself something of an ethical dilemma. Further, the SPCA disputed the extent of the allegations made against them. From the SSPV publication it is further detailed that “In Britain each year some two million such experiments are carried out, and that their booklet has been sent to MPs in the hope of outlawing this legalised torture of defenceless creatures.” As we shall later in this piece those advocating the necessity of the use animals in experiments refute the use of terms like torture and outline that the vast majority of procedures are not surgical in nature.

From the Hawick News of 22/4/1955 we hear the views of Harvey Metcalfe, secretary of the SSPV: “The colossal number of animals used and the fortunes that have been spent on cancer research have not helped one iota in combating the disease”. This then an example of the argument that animal research cannot precipitate benefits that could be directly beneficial to other species like humans, something that is not accepted by its supporters as is argued in the next article.

From the Evening Dispatch on 17/11/1955 there is a report of a speech made by Sir Henry Hallet Dale, joint winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1936. [5] “People who conducted propaganda against the inoculation of animals should not escape responsibility for the agonising deaths of children from diphtheria and of soldiers from tetanus. Such people have lost all sense of balance in their imaginative sympathies. They were guilty of self-indulgent sentimentality. It is impossible to move anywhere in modern medicine without using knowledge produced by experimental research in which living animals have often been necessary.”

In these remarks, as well as in giving his expertise, views and justifications, he also adopts some emotive language as opponents of vivisection are wont to do, and utilises some judgemental dismissive language such as accusations of sentimentality. This trait and the fact that some prominent anti- vivisection supporters like the previously mentioned Frances Power Cobbe were women, can come across as patronising.

I liked this image and short article from the collection of cuttings, describing one woman’s pledge to look after an assortment of stray dogs in her community.

In the second selection of items viewed were papers from the Vivisection and Research Defence Society 1922-1929. [6] There is a record recalling the first meeting of Royal Commission of Vivisection on 5th July 1975. Lord Lister gave evidence describing how the use of live animals in experimentation “had the effect of giving me a kind of pathological information, without which I believe I could not have made my way in the subject of antiseptics.”

In another article, reprinted from the “fight against disease of January 1927”, the argument is made that as long as humans overwhelmingly sanction the killing of animals for food and in numbers greatly exceeded those use in vivisection, then it is hypocritical to condemn the latter. It states “it is perfectly justified in using a relatively small number of animals for the study of disease and the alleviation of pain to humans and other animals.” They further stipulate that current legislation is sufficiently robust to ensure that animals do not experience any suffering and that anaesthetics are used and cruelty avoided, with any animal exposed to pain humanely destroyed.

A further critique remarks that “anti-vivisection endeavours may be in the interests of some animals, namely the experimental animals individually, but it is certainly not in the interests of the animal community as a whole, and it works directly against the interests of suffering humanity.” They also point out their assertion that 93% or experiments carried out not surgical in nature but included feeding, testing of medications and sampling of blood etc.

An example on the efficacy of vivisection upon human health advances is made in the case of diabetes, dating from 25/10/1927 addressed by Dr Grace Briscoe. “Another recent and outstanding advance has been the discovery of insulin which has given us a powerful therapeutic agent. Before this discovery there was not drug which could control diabetes, but since many valuable lives have been saved. All the experiments leading to this discovery were performed on dogs, and as far as we know, could not have been performed on any other animal.”

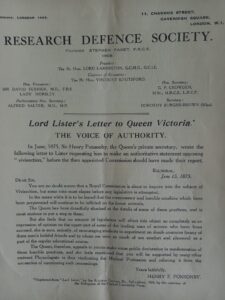

The letter above, sent on behalf of Queen Victoria to the Research Defence Society in 1875, expressed the monarch concern and dismay at the practice of vivisection and sought to receive some expression of shared concern and condemnation from them. The lengthy and thorough response from Lord Lister, however, came across in places as defiant and unyielding to any criticism.

It cited the previously detailed defences that animal experiments were essential to the advancement of human and veterinary health issues, that cruelty and pain were avoided, and that the numbers of animals involved was minor in contrast to those killed for food. One might expect the tone of the response would be more deferential given the status of the Queen but Lord Lister in places adopts a haughty and somewhat dismissive tone. He also makes some dubious and jarring observations such as “an act is cruel or otherwise, not according to the pain which it involves, but according to the mind and object of the actor.” And later: “The infliction of pain upon the brute creation is also allowed by all to be justifiable when some important interest is supposed to be served.” These remarks undermine the much-stated reassurances that pain is avoided in such experiments, and employs somewhat Old Testament views such as that “brute” animals are to be used as we please by us humans.

It was fascinating to read over these opposing views and stances, with more nuance and complexity that one might have anticipated. In a subsequent blog I shall be reporting on some more wider archive aspects of the Royal (Dick) Veterinary College in Edinburgh.

I should like to thank my supervisors Laura Beattie (Community Engagement Officer, University of Edinburgh) and Fiona Menzies, Project Archivist One Health.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_animal_testing

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Anti-Vivisection_Society#:~:text=Public%20opposition%20to%20vivisection%20led,be%20enacted%20to%20control%20vivisection.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cruelty_Free_International

[4] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/archival_objects/222483

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Hallett_Dale#:~:text=Sir%20Henry%20Hallett%20Dale%20OM,or%20Medicine%20with%20Otto%20Loewi.

[6] https://archives.collections.ed.ac.uk/repositories/2/archival_objects/217978

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Leave a Reply