Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

March 10, 2026

John Augustus Bonney’s History of the Tower of London

Posted on August 29, 2024 | in 19th Century, Archive Collections, Library & University Collections | by pbarnabyIn this post, Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement Team, looks at a manuscript history of the Tower of London written by a political radical who was himself imprisoned in the Tower.

In this blog I shall explore the Library’s collection of manuscript notes of lawyer and political reformer John Augustus Bonney compiled between 1794 and 1813 (Coll-307). Their subject is the history of the Tower of London from 1100 to 1552. Bonney himself was held in the Tower as a political prisoner from May to December 1794. He had attracted government attention as the defence lawyer for publishers charged with publishing seditious materials. With other radicals, he was arrested on suspicion of treason but was eventually released without charge. While imprisoned, Bonney conceived the idea of writing a history of the Tower. Our papers include preliminary notes taken while Bonney was captive in the Tower, early drafts on paper watermarked 1799 and 1802, and a neat copy on paper watermarked 1806.

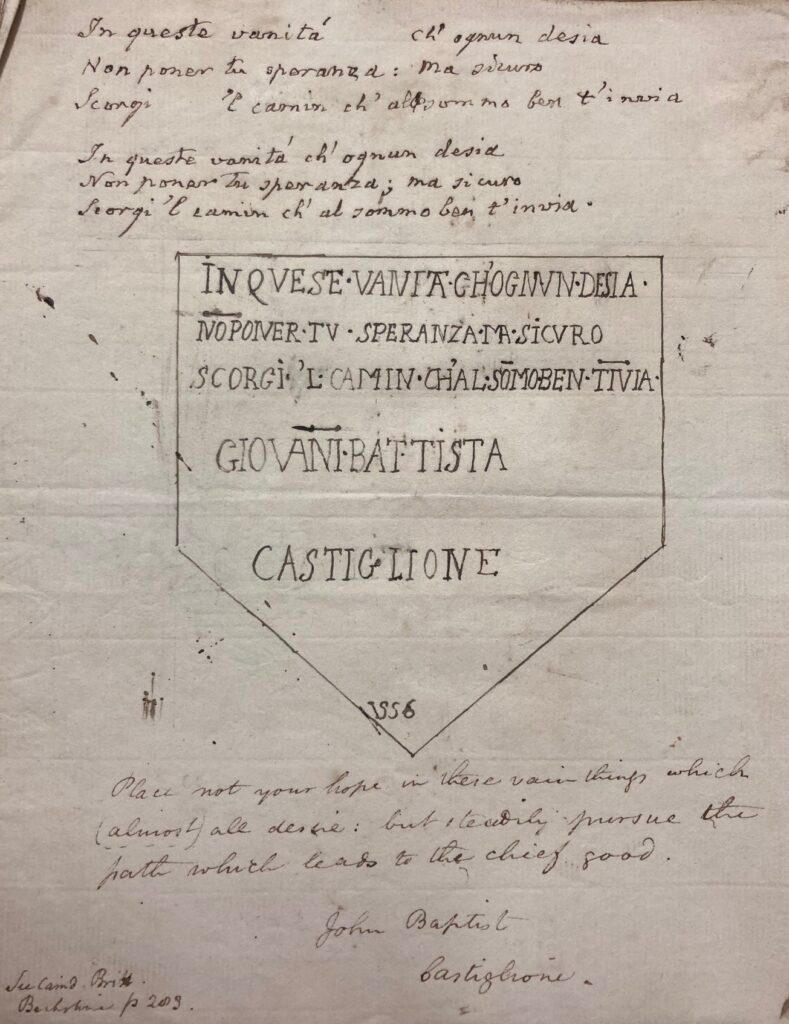

Bonney’s preliminary notes includes transcripts of some of the inscriptions etched into the walls of the Tower, such as the following by Giovanni Battista Castiglione, a humanist reformer, who was held at the Tower for suspected sedition in 1556, and tortured to such an extent that he was left permanently disabled. Bonney translates Castiglione’s words as:

Place not your hope in these vain things which (almost) all desire, but steadily pursue the path which leads to the chief good.

Transcript of inscription by Giovanni Battista Castiglione, 1556 (Coll-307/13)

Bonney tells the story of the Tower through chronological case histories of its prisoners. The cases included in this article are simply chosen as ones that piqued my curiosity. They were also selected to avoid using more famous examples well recorded elsewhere, such as the imprisonment and punishment of Anne Boleyn.

One of the earliest case histories recounts the fate of Constantine Fitz-Arnulph, following his participation in the riots that followed the annual wrestling match between Westminster and the City of London in 1221. Captured as the ringleader, he was sentenced to be hanged along with his nephew and another man. Despite offering 15,000 medieval marks (equivalent to over £12 million currently) to be pardoned, Constantine and his two associates were executed at the tower. (See Martin Fone, ‘The London Wrestling Riot of 1221’.)

Bonney also records the case of Sir Robert Tresilian, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, who was executed in 1388 for his loyalty to King Richard II in his struggle with the Lords Appellant. Bonney first describes Tresilian’s own notoriously harsh treatment of participants in the Peasants’ Revolt:

Cruel and barbarous in his temper, the Judge proceeded against the unfortunate wretches with a ferocity unknown till that time.

Prior to Tresilian’s death, we read:

the executioner stript him and found images painted upon him like the signs of the heavens, and the head of a devil. He had also concealed a parchment on which were written the names of many devils. These being removed he was hanged naked, and, after some time, that the spectators might be assured he was dead, his throat was cut.

This is an example of the sometimes fanatical religious fervours of the period, obsessing over diabolical intents, and somewhat akin to tactics deployed in persecutions and punishments of those deemed to be practising witchcraft.

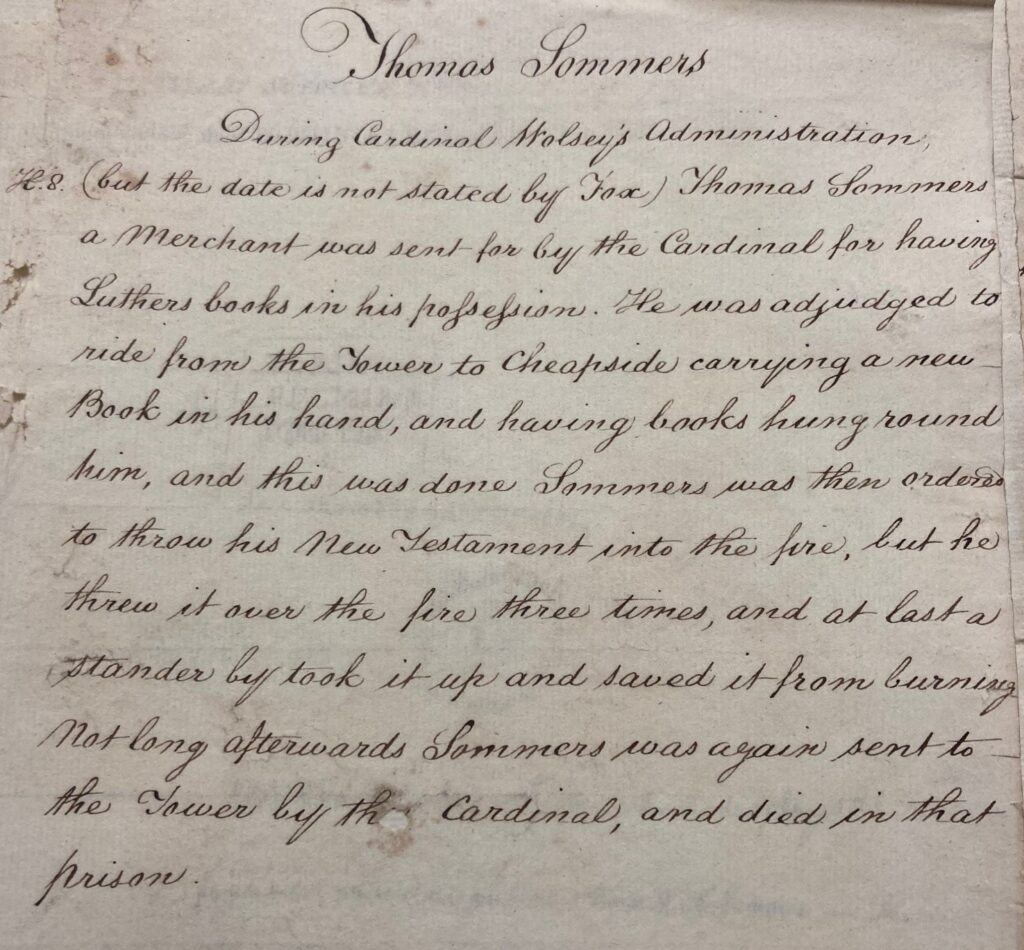

Bonney outlines the case of Thomas Sommers, involving religious persecution of Protestants during Cardinal Wolsey’s administration (1515-1529):

Thomas Sommers, a merchant, was sent for by the Cardinal for having Luther’s books in his possession. He was adjudged to ride from the Tower to Cheapside carrying a new Book in his hand, and having books hung round him, and this was done. Sommers was then ordered to throw his New Testament into the fire, but he threw it over the fire three times, and at last a stander by took it up and saved if from burning. Not long afterwards Sommers was again sent to the tower and died in that prison.

This bizarre public shaming punishment of Sommers and his subsequent death in prison for simply upholding his beliefs was a brutal example of the religious intolerance of the period.

‘Thomas Sommers’ (Coll-307/6)

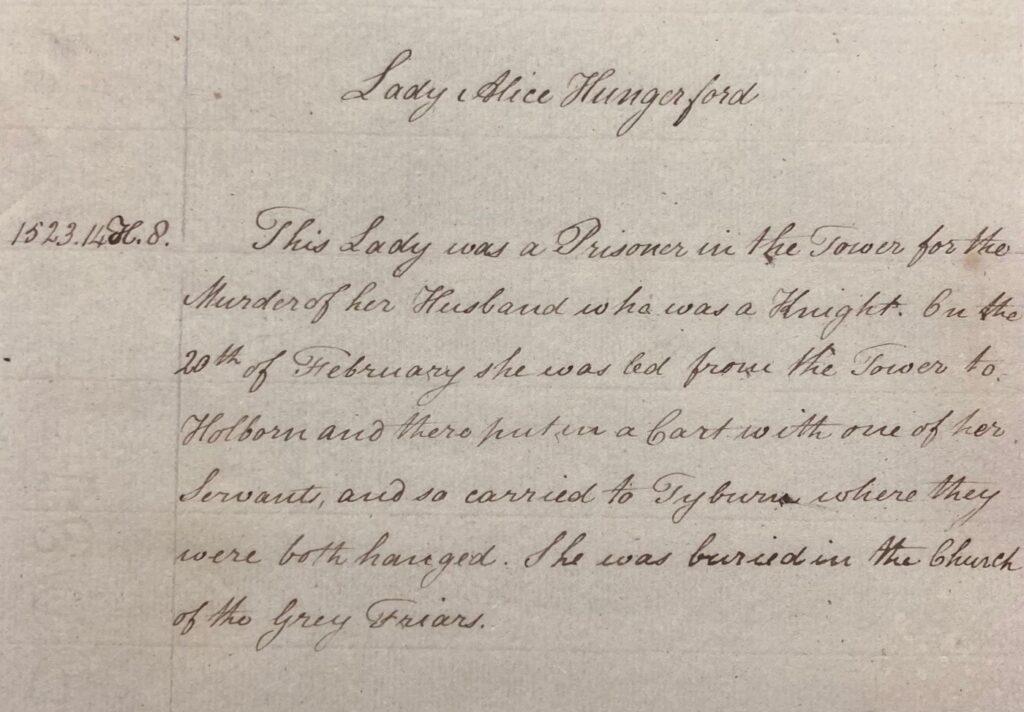

Not all prisoners, though, were held for political or religious reasons. A case of the prosecution for murder by Lady Alice or Agnes Hungerford in 1523 is recorded:

The lady was a prisoner in the Tower for the murder of her husband who was a Knight. On the 20th of February he was led from the Tower to Holborn and there put in a cart with one of her servants, and so carried to Tyburn where they were both hanged.

‘Lady Alice Hungerford’ (Coll-307/15)

There are instances of apparently lesser crimes that nevertheless could be subject to the harshest penalty. One example from the 16th century is that of a coiner:

On the 25th of April one of the persons employed in the Mint at the Tower was drawn from thence to Tyburn and there hanged for making false money.

The severeness of the sentence also revealing in that of the desperate risks the individual was taking in committing such a crime within the Tower presumably well aware of the likely consequences if discovered.

Not all the case histories involve instances where prisoners were executed. In 1530, Thomas Philips was imprisoned for practising Protestantism in defiance of the then prevailing establishment of the Catholic Church.

The charges against him were for holding the protestant opinions upon the subjects of purgatory, Images, the sacrament of the altar &c. and it was also charged that being searched in the Tower, Tracey’s English translation of the Testament was found upon him, and cheese and butter were found in his apartment in the time of Lent […]. He was frequently examined by Sir Thomas More the Lord Chancellor, but nothing was found upon him except for the possession of the testament and the cheese and butter[…].

The bizarre minutiae of the foodstuffs are a somewhat bleakly comic detail to modern eyes amidst the brutal treatment meted out at the prison. Bonney notes that Phillips remained incarcerated for some years, and went on to hold the position of keeper of the prison before gaining his freedom.

On reading these case histories it is striking generally how harsh the punishments were, and this is exacerbated by the fact that the evidence-based level of charges, trials and convictions during these centuries would have been distinctly less fair and favourable to those accused, who were not then routinely provided with a lawyer or legal defence equivalents.

The Papers of John Augustus Bonney also contain a collection of family documents and portraits, including an engraving of Bonney himself, depicted with the Tower of London looming in the background. The Tower’s presence in the portrait may be intended to hint at how Bonney’s prison experience cast a dark shadow over him future career, leaving him dogged by suspicions that he was a dangerous revolutionary.

‘John Augustus Bonney’, engraved by Peltro William Tomkins after W. White (Coll-307)

In conclusion it was intriguing if unsettling to read through these concisely written case summaries by Bonney. I’d like to thank my supervisor Laura Beattie (University of Edinburgh Community Engagement Officer) and Paul Barnaby (Modern Literary Collections Curator).

Bibliography

John Bugg, ‘Bonney, John Augustus (1763-1813)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography<https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/109526>

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....